2018 Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy & International Broadcasting Focus on Fy 2017 Budget Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Offered Trump Campaign Cooperation US Govt Seeks ‘Substantial’ Jail Term for Cohen • Comey Grilled Again in Congress

InternationalEstablished 1961 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2018 Muslims rally to defend privileges in As election approaches, religious tensions surge in Indian village multiethnic Malaysia Page 9 Page 8 WASHINGTON: Former FBI Director James Comey (center) talks to reporters following a closed House Judiciary Committee meeting to hear his testimony on Capitol Hill on Friday. — AFP Russian offered Trump campaign cooperation US govt seeks ‘substantial’ jail term for Cohen • Comey grilled again in Congress NEW YORK: US prosecutors have revealed that a himself has now admitted, with respect to both pay- posed” a meeting between Trump and Russian ate who US officials suspect is a Russian intelligence Russian offered cooperation to Donald Trump’s cam- ments, he acted in coordination with and at the President Vladimir Putin, claiming it could have a operative, and about his contacts with Trump adminis- paign as early as 2015, declaring that the president’s direction of Individual-1,” the document reads, refer- “phenomenal” impact “not only in political but in a tration officials after striking a plea agreement. The ex-lawyer Michael Cohen had provided “relevant” and ring to Trump. business dimension as well”. “Cohen, however, did not White House similarly dismissed that filing, arguing it “substantial” help to the Russia investigation. In a sep- Robert Mueller, the special counsel heading up the follow up on this invitation,” the filing added. “says absolutely nothing about the President”. “Once arate case, federal prosecutors Friday demanded “sub- probe into Russian meddling in the 2016 vote, followed The former fixer last week pleaded guilty to lying again the media is trying to create a story where there stantial” jail time of between 51 to 63 months - four to up with a separate filing saying Cohen had made “sub- to Congress in connection with a Moscow real estate isn’t one,” said Sanders. -

Congress and the War in Yemen: Oversight and Legislation 2015-2019

Congress and the War in Yemen: Oversight and Legislation 2015-2019 Updated February 1, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45046 Congress and the War in Yemen: Oversight and Legislation 2015-2019 Summary This product provides an overview of the role Congress has played in shaping U.S. policy toward the conflict in Yemen. Summary tables provide information on legislative proposals considered in the 115th and 116th Congresses. Various legislative proposals have reflected a range of congressional perspectives and priorities, including with regard to the authorization of the activities of the U.S. Armed Forces related to the conflict; the extent of U.S. logistical, material, advisory, and intelligence support for the coalition led by Saudi Arabia; the approval, disapproval, or conditioning of U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia; the appropriation of funds for U.S. operations in support of the Saudi-led coalition; the conduct of the Saudi-led coalition’s air campaign and its adherence to international humanitarian law and the laws of armed conflict; the demand for greater humanitarian access to Yemen; the call for a wider government assessment of U.S. policy toward Yemen and U.S. support to parties to the conflict; the nature and extent of U.S.-Saudi counterterrorism and border security cooperation; and the role of Iran in supplying missile technology and other weapons to the forces of the Houthi movement. The 116th Congress may continue to debate U.S. support for the Saudi-led coalition and Saudi Arabia’s conduct of the war in Yemen, where fighting has continued since March 2015. -

(USAGM) Board Meeting Minutes, 2017-2019

Description of document: U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) Board Meeting minutes, 2017-2019 Requested date: 21-October-2019 Release date: 12-November-2019 Posted date: 02-December-2019 Source of document: USAGM FOIA OFFICE Room 3349 330 Independence Ave. SW Washington, D.C. 20237 ATTN: FOIA/Privacy Act Officer Fax: (202) 203-4585 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. UNITED STATES U.S. AGENCY FOR BROADCASTING BOARD OF GLOBAL MEDIA GOVERNORS 330 Independence Avenue SW I Washington, DC 20237 I usagm.gov Office of the General Counsel November 12, 2019 RE: Request Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act - FOIA #FOIA20-002 This letter is in response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request dated October 21 , 2019 to the U.S. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Engaging and Empowering Our Audience

2012 Annual Report U.S. INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING Engaging and Empowering Our Audience IBB bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ L etter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 English CENTRAL (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA* Greek Afaan Oromoo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Overview 6 T hreats Against Journalists 10 Kinyarwanda Serbian Kirundi Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian International 2012 Election Coverage 18 Kazakh Crimean Tatar Broadcasting Bureau 12 Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Uzbek Ukrainian EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Voice of America 20 R adio Free Europe/ Khmer NEAR EAST/ Radio Liberty 26 Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Uyghur SOUTH ASIA Vietnamese Bangla Dari Pashto Office of Cuba Broadcasting 30 R adio Free Asia 34 Persian Urdu * In 2012, the BBG worked toward [I]f you want to be free, you have to know how free people live. establishing broadcasts in Songhai If you’ve never known how free people live, you might not ever know and Bambara. “ that you are not free. This is why programs like Radio Free Asia are On cover: A Syrian man uses his mobile phone so very important. – Aung San Suu Kyi to capture demonstrators marching in the neighborhood of Bustan Al-Qasr, Aleppo, Syria. Middle East Broadcasting Board Broadcasting Networks 38 of Governors 44 Burmese opposition leader” Aung San Suu Kyi waves to admirers before the April by-elections, (AP Photo, Andoni Lubaki) A wards & Honors 42 Financial Highlights 47 in which she became a member of parliament. -

Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences

DISCUSSION PAPERS IN DIPLOMACY Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding: Conceptual Similarities and Differences Gyorgy Szondi Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ ISSN 1569-2981 DISCUSSION PAPERS IN DIPLOMACY Editors: Virginie Duthoit & Ellen Huijgh, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Managing Editor: Jan Melissen, Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ and Antwerp University Desk top publishing: Desiree Davidse Editorial Board Geoff Berridge, University of Leicester Rik Coolsaet, University of Ghent Erik Goldstein, Boston University Alan Henrikson, Tufts University Donna Lee, Birmingham University Spencer Mawby, University of Nottingham Paul Sharp, University of Minnesota Duluth Copyright Notice © Gyorgy Szondi, October 2008 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy, or transmission of this publication, or part thereof in excess of one paragraph (other than as a PDF file at the discretion of the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’) may be made without the written permission of the author. ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to explore potential relationships between public diplomacy and nation branding, two emerging fields of studies, which are increasingly being used in the same context. After examining the origins of the two concepts, a review of definitions and conceptualisations provide a point of departure for exploring the relationship between the two areas. Depending on the degree of integration, five conceptual models are outlined, each with potential pitfalls as well as advantages. According to the first approach, public diplomacy and nation branding are unrelated and do not share any common grounds. In other views, however, these concepts are related and it is possible to identify different degrees of integration between public diplomacy and nation branding. -

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development ______

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 14 October 2017 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer-reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments Watch - Selected Updates from 30+ entities :: INGO/Consortia/Joint Initiatives Watch - Media Releases, Major Initiatives, Research :: Foundation/Major Donor Watch -Selected Updates :: Journal Watch - Key articles and abstracts from 100+ peer-reviewed journals :: Week in Review A highly selective capture of strategic developments, research, commentary, analysis and announcements spanning Human Rights Action, Humanitarian Response, Health, Education, Holistic Development, Heritage Stewardship, Sustainable Resilience. -

U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering

2010 Annual Report U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ English CENTRAL Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA Greek Afan Oromo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Kinyarwanda Serbian Kirundi Overview 6 Voice of America 14 Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian Kazakh Crimean Tatar Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Radio Free Europe Radio and TV Martí 24 Uzbek Ukrainian 20 EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Khmer NEAR EAST/ Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Middle East Radio Free Asia Uyghur 28 Broadcasting Networks 32 Vietnamese SOUTH ASIA Bangla Dari Pashto Persian Urdu International Broadcasting Board On cover: An Indonesian woman checks Broadcasting Bureau 36 Of Governors 40 her laptop after an afternoon prayer (AP Photo/Irwin Fedriansyah). Financial Highlights 43 2 Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 Voice of America 14 “This radio will help me pay closer attention to what’s going on in Kabul,” said one elder at a refugee camp. “All of us will now be able to raise our voices more and participate in national decisions like elections.” RFE’s Radio Azadi distributed 20,000 solar-powered, hand-cranked radios throughout Afghanistan. 3 In 2010, Alhurra and Radio Sawa provided Egyptians with comprehensive coverage of the Egyptian election and the resulting protests. “Alhurra was the best in exposing the (falsification of the) Egyptian parliamentary election.” –Egyptian newspaper Alwafd (AP Photo/Ahmed Ali) 4 Letter from the Board TO THE PRESIDENT AND THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES On behalf of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) and pursuant to Section 305(a) of Public Law 103-236, the U.S. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Who We Are

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Who We Are The BBG is the independent federal government agency that oversees all U.S. civilian international media. This includes the Voice of America, Radio Estonia Russia Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the Latvia Office of Cuba Broadcasting, Radio Lithuania Belarus Free Asia, and the Middle East Ukraine Kazakhstan Broadcasting Networks, along with Moldova Bosnia-Herz. Serbia Kosovo Georgia Uzbekistan the International Broadcasting Mont. Macedonia Armenia Kyrgyzstan Turkey Azerbaijan Turkmenistan Albania Tajikistan Bureau. BBG is also the name of the Lebanon North Korea Tunisia Pal. Ter. Syria Afghanistan China board that governs the agency. Morocco West Bank & Gaza Iraq Iran Jordan Kuwait Algeria Libya Egypt Pakistan Western Sahara Saudi Bahrain Mexico Cuba Qatar Bangladesh Taiwan BBG networks are trusted news Haiti Arabia U.A.E. Burma Dominican Mauritania Mali Laos Cape Verde Oman sources, providing high-quality Honduras Republic Senegal Niger Sudan Eritrea Guatemala The Gambia Burkina Chad Yemen Thailand Vietnam Phillipines Nicaragua Guinea-Bissau Faso Djibouti journalism and programming to more El Salvador Venezuela Guinea BeninNigeria Cambodia Costa Rica Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Panama Liberia Afr. Rep. Sudan Somalia Togo Cameroon Singapore than 215 million people each week. Colombia Cote d’Ivoire Uganda Equatorial Guinea Congo Dem. Rep. Seychelles Ecuador Sao Tome & Principe Rwanda They are leading channels for Of Congo Burundi Kenya Gabon Indonesia information about the United States Tanzania Comoros Islands Peru Angola Malawi as well as independent platforms for Zambia Bolivia Mozambique Mauritius freedom of expression and free press. Zimbabwe Paraguay Namibia Botswana Chile Madagascar Mission: To inform, engage and connect people around the Swaziland South Lesotho Uruguay Africa world in support of freedom and democracy. -

Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-Degree Listening and Evaluation Approach to Assess Country Images

Perspectives Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-degree Listening and Evaluation Approach to Assess Country Images By Diana Ingenho & Jérôme Chariatte Paper 2, 2020 Solving the Public Diplomacy Puzzle— Developing a 360-Degree Integrated Public Diplomacy Listening and Evaluation Approach to Analyzing what Constitutes a Country Image from Different Perspectives Diana Ingenhoff & Jérôme Chariatte November 2020 Figueroa Press Los Angeles SOLVING THE PUBLIC DIPLOMACY PUZZLE—DEVELOPING A 360-DEGREE INTEGRATED PUBLIC DIPLOMACY LISTENING AND EVALUATION APPROACH TO ANALYZING WHAT CONSTITUTES A COUNTRY IMAGE FROM DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES by Diana Ingenhoff & Jérôme Chariatte Guest Editor Robert Banks Faculty Fellow, USC Center on Public Diplomacy Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstores Produced by Crestec, Los Angeles, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Notice of Rights Copyright © 2020. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC University Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. -

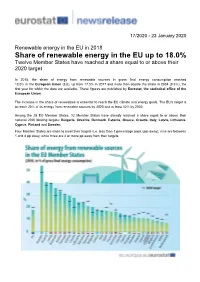

Share of Renewable Energy in the EU up to 18.0% Twelve Member States Have Reached a Share Equal to Or Above Their 2020 Target

17/2020 - 23 January 2020 Renewable energy in the EU in 2018 Share of renewable energy in the EU up to 18.0% Twelve Member States have reached a share equal to or above their 2020 target In 2018, the share of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption reached 18.0% in the European Union (EU), up from 17.5% in 2017 and more than double the share in 2004 (8.5%), the first year for which the data are available. These figures are published by Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. The increase in the share of renewables is essential to reach the EU climate and energy goals. The EU's target is to reach 20% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020 and at least 32% by 2030. Among the 28 EU Member States, 12 Member States have already reached a share equal to or above their national 2020 binding targets: Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Cyprus, Finland and Sweden. Four Member States are close to meet their targets (i.e. less than 1 percentage point (pp) away), nine are between 1 and 4 pp away, while three are 4 or more pp away from their targets. Sweden had by far the highest share, lowest share in the Netherlands In 2018, the share of renewable sources in gross final energy consumption increased in 21 of the 28 Member States compared with 2017, while remaining stable in one Member State and decreasing in six. Since 2004, it has significantly grown in all Member States. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today.