A Philosophy and an Approach to Teaching Non-Professional-Track Violin Students Based on the Premise That Music Is a Universal Value Available to All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

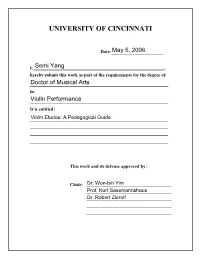

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

La Société Philharmonique

The Historic New Orleans Collection & Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra Carlos Miguel Prieto Adelaide Wisdom Benjamin Music Director and Principal Conductor Pr eseNT Identity, History, Legacy La Société PhiLh ar monique Thomas Wilkins, conductor Walter Harris Jr., speaker Kisma Jordan, soprano Joseph Meyer, violin Jean-Baptiste Monnot, organ/piano Phumzile Sojola, tenor THursday, February 10, 2011 Cathedral-basilica of st. Louis, King of France New Orleans, Louisiana Fr Iday, February 11, 2011 slidell High school slidell, Louisiana The Historic New Orleans Collection and the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra gratefully acknowledge rev. Msgr. Crosby W. Kern and the staff of the st. Louis Cathedral for their generous support and assistance. The musical culture of New Orleans’s free people of color and their descendants is one of the most extraordinary aspects of Louisiana history, and it is part of a larger, shared legacy. Only within the context of the development of african music in the New World can the contributions of these sons and daughters of Louisiana be fully appreciated. The first africans arrived in the New World with the initial wave of spanish colonization in the early sixteenth century. Interactions among european, african, and indigenous populations yielded new forms of cultural expression—although african music in the New World remained strongly dependent on wind instruments (such as ivory trumpets), drums, and call-and-response patterns. as early as 1572, africans were gathering in front of the famous aztec calendar stone in Mexico City on sunday afternoons to dance and sing. When Viceroy antonio de Mendoza triumphantly entered Lima on august 31, 1551, his procession’s route was lined with african drummers. -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another. -

Wishmaker Fall 2019

WishmakerVOL 28 ISSUE 2 / FALL/WINTER 2019 … when you get to be part of these It is humbling, wishes … it helps a triumph of balance the human spirit things out. realized for all to witness. Our family will carry this incredible Make-A-Wish was in our wish there for us, and hearts forever. words cannot express ... thank you how thankful for all that you have I am ... done for him and countless others. The Power of a Wish … In Their Own Words With gratitude from the Board Chair and CEO To Our Valued Donors and Volunteers, Thank you for helping us to transform lives, one wish at a time! One of the most gratifying aspects of our involvement with the Make-A-Wish® Foundation is the wide range of people who generously give of their time, talent and treasure to help make magical wishes come true for children and teens with critical illnesses. In this Fall/Winter issue of Wishmaker, we celebrate the beauty of that colorful spectrum of people and organizations who are part of our Make-A-Wish® Northeast New York family. As our Director of Marketing & Communications Mark McGuire so wisely notes: Nothing speaks to the power of a wish better than the testimony of those who are directly engaged in making the wish magic happen. In this issue we present to you, in their own words, several beautiful and compelling first- person reflections. Among them: Wish mom Noelle recounting her daughter’s wish experience in Florida; the family of wish alum Jordan Waner speaking to the impact of his wish as he graduated from high school; wish alum Joe Watroba’s wish journey that led him and his family Sarah A. -

Violin Makers Flournal

rhf ViolinMakers flournal OCT OBE R - NOVEMBE R, 1961 THE. OFFICIAL PUBLICATION. OF THE VIOLIN MAKERS ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA ''THE MADONNA" Superb Wood Carving by Clifford Hoing (see story, page 1) Issued as an Educational Feature to encourage and develop the art of violin making. • Eudoxa Flexocor Complete line of Violinists &: Makers Supplies. Send for Art Catalogue. Distributors of Pirastro Wondertone StrJngs in Canada George Heinl, Toronto- James Croft &: Son, Winnipeg Peate Music Supplies, '�ontreal Landers Distributors Ltd., Vancouver, B. C. 1JttaH lmfort Comfan( 5948 iltlantic Blv�. + m�(U?OO�t Calif. .. 1l.S.JI. Strinsed Instruments and Accessories + Old roaster '.Bows + Violins + Violas + Celli .. 'Rare �ks Write for Catalogue and Price List. Discount to Maker and Musicians. OLD ITALIAN CREMONA VARNISH FOR VIOLINS Keep in Contact with the Players, Fillers for Tone Stain for Shading Easily Applied They are Your Customers Made from Fossil Resins The American String Teachers Association is a non-profit ALL COLORS INCLUDING NATURAL musical and educational organization established in 1946. Oil or Spirit It serves string and orchestra teachers and students. Promotes and encourages professional and amateur string Prices Postpaid oz. 2 $1.50 and orchestra study and performance. 4 oz. $2.50 8 oz. $4.50 The American String Teachers Association has'a develop S. KUJAWA ment and progressive program which includes: 1958 East Hawthorne St. Paul Minn., U.S.A. 1. Summer Workshops for string teachers and amateur 19, ' chamber music players. 1960 conferences were held at Colorado Springs, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Put- In-Bay, Ohio and Interlochen Michigan. 2. Publications. A newsletter STRING TALK is published four times each ,Year. -

O Legado De Pablo De Sarasate

O LEGADO DE PABLO DE SARASATE Lígia Maria Leitão Soares Silva Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Interpretação ORIENTADORA: Professora Doutora Vanda de Sá ÉVORA, NOVEMBRO DE 2018 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ¡Un genio! ¡He practicado catorce horas diarias durante treinta y siete años, y ahora me llaman genio! Pablo de Sarasate ~ iii ~ ~ iv ~ À memória dos meus pais ~ v ~ ~ vi ~ Agradecimentos Concluir um doutoramento em Música e Musicologia na especialidade de Interpretação implica uma longa trajectória em que a conciliação do trabalho escrito com a prática do instrumento dificilmente se consegue fazer de modo regular e constante. Este trabalho não teria sido possível sem o apoio de diversas pessoas às quais deixo aqui os meus sinceros agradecimentos. Começo por agradecer à Professora Doutora Vanda de Sá, orientadora deste trabalho, a disponibilidade e o interesse, as sugestões que fez e a generosidade com que disponibilizou algumas fontes. Agradeço ainda a forma estimulante como contribuiu para o alargamento de algumas problemáticas iniciais, a amizade demonstrada e a disponibilidade para ler e aconselhar sobre o conteúdo das notas aos programas que elaborei para os recitais que realizei como parte deste doutoramento. Agradeço ao Professor Doutor Félix Andrievsky todos os conhecimentos que me transmitiu ao longo dos anos em que trabalhei com ele e sem os quais não teria sido possível realizar este trabalho. Agradeço também a disponibilidade que continua a ter para mim, cerca de trinta anos após o primeiro contacto, o estímulo, os conselhos e o interesse com que ouviu grande parte do repertório que interpretei nos recitais. -

New 6-Page Template a 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1

573000bk Kummer:New 6-page template A 27/4/16 9:32 PM Page 1 Frédéric Kummer (1797–1879) und François Schubert (1808–1878) zu den bekanntesten Bühnenwerken des Opern- und führt im pianissimo wieder nach G-dur und zum Dreivier- Duos Concertants pour Violon et Violoncelle Ballettkomponisten Louis Joseph Ferdinand Hérold teltakt zurück – zunächst als ruhiges Moderato molto mit (1791–1833) und zu den beliebtesten Singspielen des 19. der Melodie im Violoncello, dann als abschließendes Friedrich August (alias Frédéric) Kummer wurde am 5. Unterricht bei seinem Vater und bei Antonio Rolla (1798- Jahrhunderts gehörte. Das Duo in der Tonart D-dur beginnt Allegro molto. August 1797 in Meiningen geboren. Sein Vater Friedrich 1837) wurde er in Paris von Charles Philippe Lafont (1781- mit einem Allegro, das neben einigen lieblichen Momenten Die Deux Duos de Concert pour Violon et Violoncelle August sen. (1770-1849) war zunächst Oboist in der 1839) ausgebildet, der seinerseits bei Rodolphe Kreutzer viel virtuoses Passagenwerk enthält. Von hier aus führt der op. 52 schließlich beginnen mit einem Souvenir de Fra Hofkapelle des Herzogs von Sachsen-Meiningen, und Pierre Rode studiert hatte. Da man ihn bisweilen mit Weg zu einem Andantino mit zwei Variationen, denen sich Diavolo, der wohl besten opéra-comique des Autorenteams übersiedelte aber mit seiner Familie bald nach der Geburt dem weitaus berühmteren Franz Schubert aus Wien ein Melancolico in Moll und im Dreivierteltakt anschließt. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber (1782–1871) und Eugène seines Sohnes nach Dresden und gab seinem Sprössling verwechselte, nahm er in Paris, wo er unter anderem mit Danach werden die ursprüngliche Tonart und der Scribe (1791–1861), dessen Namen wir üblicherweise im Frédéric den ersten Musikunterricht, bevor dieser von Justus Chopin Freundschaft schloss, den Namen »François« an. -

Henry Thoreau, from Which He Would Obtain Plutarch Materials Plus Quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’S “Epigram on Anacreon” That He Would Recycle in a WEEK.)

HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 EVENTS OF 1813 General Events of 1814 SPRING JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH SUMMER APRIL MAY JUNE FALL JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER WINTER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Following the death of Jesus Christ there was a period of readjustment that lasted for approximately one million years. –Kurt Vonnegut, THE SIRENS OF TITAN THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence, Rhode Island: John Carter. THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence: John Carter. Sold also by George Wanton, Newport. 21-year-old Edward Hitchcock calculated and published a COUNTRY ALMANAC (recalculated and reissued each year to 1818). John Farmer’s “A Sketch of Amherst, New Hampshire” (2 COLL. MASS. HIST. SOC. II. BOSTON). Noah Webster, Esq. became a member of the Massachusetts General Court (he would serve also in 1815 and 1817). Carl Phillip Gottfried von Clausewitz was reinstated in the Prussian army. EVENTS OF 1815 HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 The 2d of 3 volumes of a revised critical edition of an old warhorse, ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA AD FIDEM CODICIS OLIM PALATINI NUNC PARISINI EX APOGRAPHO GOTHANO EDITA ..., prepared by Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Jacobs, appeared in Leipzig (the initial volume had appeared in 1813 and the final volume would appear in 1817). ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA (My working assumption, for which I have no evidence, is that this is likely to have been the unknown edition consulted by Henry Thoreau, from which he would obtain Plutarch materials plus quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’s “Epigram -

2014-06 December EBBC Newsletter.Pub

Membership Newsletter November/December 2014 Volume 9 Issue 6 Editor: Karen Hefter Upcoming Play Out Schedule President’s Message: February 27th Orinda Masonic Lodge Crab Feed 7:00 pm - 8:00 pm We should all be very proud of our club - our club is for all of us!!! As members of the club, we are all vital and func- **No EBBC** tioning parts. The board positions are open to all regular and lifetime club members. I have person- 12/24 or 12/31 ally discovered this year that the President's chair isn't all that demanding, nor are the other board See you next chairs. The fact is that, as long as the board func- year! tions as a team for the benefit of the club and all of its members, no single board chair is too demand- ing. This is because there is always someone in the club to provide assistance and/or support, when and if needed. The most impor- tant savior for me this last year has been our past president – Sheila Welt. Monthly Board Meetings Our club was formed over 50 years ago as an interest group for the banjo that 2nd Tuesdays, 7pm included professional banjoists, beginners and families just wanting to have fun learning and playing together. My wish is that the club will continue with this Sheila Welt’s House concept but, because of changing times, we will surely need to continue to be Next Meeting: Jan. 13th open to making ongoing adjustments. In addition to finding paying venues to accumulate funds, the board has decided that we will play more benefit gigs for schools and non-profit organizations in East Bay Banjo Club Meets the future. -

The Violin Player Broadcast 1

The Violin Player. Broadcast Draft The Violin Player A radio play by Catherine Fargher Broadcast ABC radio National ‘AIRPLAY’ March 14th 2009 © Catherine Fargher 2009 PO Box 178 St Pauls NSW 2031 Email:[email protected] Ph/fax:02 93145121 Mob:0415442209 1 The Violin Player. Broadcast Draft The Violin Player The Battle of the Somme 1918…A young man with a violin… Recreation leave and Mustard Gas … A great uncle lost…His diary discovered…A young man busking in Paris 1981…his great uncle’s violin stolen at a Paris station… A piecing together of song, sound and memory. A year ago I came into possession of the original diary of my Great-Uncle Philip, who fought and died at the Somme battlefields in France during WWI. He was 19 years old, and the early diary entries are those of a young man who is at first excited, then disillusioned, and finally destroyed by the war he has gone to fight. He was the victim of the Mustard Gas campaigns which were used by the Germans in WWI French campaigns, including the battle of the Somme and resulted in the death of thousands of young Australian men. His youth brought abruptly to an end in a way I can only try to understand from the diary entries and the space of hidden memories between the lines of the faintly written diary. The way our family knew Philip was through his violin. My brother and I inherited his fiddle, inlaid with mother of pearl in the fingerboard, and it had always been ‘Philips violin’.