Some Preliminary Notes on the 1980S Airbrush Art Ursula-Helen Kassaveti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 7-2016 Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction Arthur B. Evans DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Arthur B. "Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction." Science Fiction Studies Vol. 43, no. 2, #129 (July 2016), pp. 194-206. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 194 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 43 (2016) Arthur B. Evans Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction Pawe³ Frelik, in his essay “The Future of the Past: Science Fiction, Retro, and Retrofuturism” (2013), defined the idea of retrofuturism as referring “to the text’s vision of the future, which comes across as anachronistic in relation to contemporary ways of imagining it” (208). Pawe³’s use of the word “anachronistic” in this definition set me to thinking. Aren’t all fictional portrayals of the future always and inevitably anachronistic in some way? Further, I saw in the phrase “contemporary ways of imagining” a delightful ambiguity between two different groups of readers: those of today who, viewing it in retrospect, see such a speculative text as an artifact, an inaccurate vision of the future from the past, but also the original readers, contemporary to the text when it was written, who no doubt saw it as a potentially real future that was chock-full of anachronisms in relation to their own time—but that one day might no longer be. -

Clarence Williams

MUNI 2017-2 – Flute 1-2 Shooting the Pistol (Clarence Williams) 1:26 / 1:17 Clarence Williams Orchestra: Ed Allen-co; Charlie Irvis-tb; possibly Arville Harris-cl, as; Alberto Socarras-fl; Clarence Williams-p; Cyrus St. Clair-tu New York, July 1927 78 Paramount 12517, matrix number 2837-2 / CD Frog DGF37 3 I’ll Take Romance (Ben Oakland) 2:39 Bud Shank-fl; Len Mercer and His Strings Bud Shank With Len Mercer Strings: Giulio Libano (trumpet) Appio Squajella (flute, French horn) Glauco Masetti (alto sax) Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Eraldo Volonte (tenor sax) Fausto Pepetti (baritone sax) Bruno De Filippi (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Jimmy Pratt (drums) with unidentified harp and strings, Len Mercer (arranger, conductor) Milan, Italy, April 4 & 5, 1958 LP World Pacific WP-1251, Music (It) EPM 20096, LPM 2052 4-5 What’ll I Do (Irving Berlin) 1:26 / 1:23 Bud Shank-fl; Bob Cooper-ob; Bud Shank - Bob Cooper Quintet: Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Bob Cooper (tenor sax, oboe) Howard Roberts (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Chuck Flores (drums) Capitol Studios, Hollywood, CA, first session, November 29, 1956 LP Pacific Jazz X-634, PJ 1226, matr. ST-1894 / CD Mosaic MS-010 6-7 Flute Bag (Rufus Harley) 2:06 / 2:15 Herbie Mann.fl; Rufus Harley-bagpipes; Roy Ayers (vibes) Oliver Collins (piano) James Glenn (bass) Billy Abner (drums) "Village Theatre", NYC, 2nd show, June 3, 1967 LP Atlantic SD 1497, matr. 12589 8-10 Moment’s Notice (John Coltrane) 4:58 / 1:04 / 0:52 Hubert Laws-fl; Ronnie Laws-ts; Bob James-p, elp, arranger; Gene Bertoncini-g; Ron Carter-b; Steve -

Budget Cuts Spare School Programs W Here the Beaches

MAY 25, 1994 40 CENTS VOLUME 24, NUMBER 21 Budget cuts spare school programs assessed at BY LAUREN JAEGER $ 1 20,000 Staff W riter would see an total of $810,000 was cut increase of from the defeated 1994-95 $156, to a A Matawan-Aberdeen proposed total tax of school budget. $2,402. As required by law, the councils of Before the Matawan and Aberdeen met last week, Cuts were along with the regional board of educa made, the rate tion, to amend the defeated budget, was $2 .10 for which originally proposed $33,532,113 A b e r d e e n ; in current expense and $28,926 in capital 2.05 for outlay. M ataw an — The new school tax rate will be $2.05 translating to a Brian Murphy per $100 assessed value for Aberdeen yearly tax rate residents, and $2.01 per $100 of assessed on a $120,000 property of $2,530 for an home value for Matawan residents. Aberdeen homeowner and $2,460 for In other words, this means that an M atawan homeowner. Marlboro High School’s Amy Feaster (gold jersey) and Middletown North’s Aberdeen resident with a home assessed Matawan’s Mayor Robert Shuey was Ann Marie Sacco hook up in a battle for the ball during a Shore at $ 120,00 would see an increase in the pleased by what he said was a smooth Conference A North Division soccer match won by the Mustangs, 2-1, on school tax rate of $95, bringing the bill meeting between the three parties and May 18 in Marlboro. -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker. -

The Future Past: Intertextuality in Contemporary Dystopian Video Games

The Future Past: Intertextuality in Contemporary Dystopian Video Games By Matthew Warren CUNY Baccalaureate for Unique and Interdisciplinary Studies Submitted to: Timothy Portlock, Advisor Hunter College Lee Quinby, Director Macaulay Honors College Thesis Colloquium 9 May 2012 Contents I. Introduction: Designing Digital Spaces II. Theoretical Framework a. Intertextuality in the visual design of video games and other media b. Examining the established visual iconography of dystopian setting II. Textual Evidence a. Retrofuturism and the Decay of Civilization in Bioshock and Fallout b. Innocence, Iteration, and Nostalgia in Team Fortress and Limbo III. Conclusion 2 “Games help those in a polarized world take a position and play out the consequences.” The Twelve Propositions from a Critical Play Perspective Mary Flanagan, 2009 3 Designing Digital Spaces In everyday life, physical space serves a primary role in orientation — it is a “container or framework where things exist” (Mark 1991) and as a concept, it can be viewed through the lense of a multitude of disciplines that often overlap, including physics, architecture, geography, and theatre. We see the function of space in visual media — in film, where the concept of physical setting can be highly choreographed and largely an unchanging variable that comprises a final static shot, and in video games, where space can be implemented in a far more complex, less linear manner that underlines participation and system-level response. The artistry behind the fields of production design and visual design, in film and in video games respectively, are exemplified in works that engage the viewer or player in a profound or novel manner. -

Wasn't the Future Wonderful?

Wasn’t the Future Wonderful? UG7_Pascal Bronner & Thomas Hillier_ 2017/18 Image: Cathedral City, 1988. Iskander Galimov Image: Cathedral City, “No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be.” - Isaac Asimov - If Wikipedia is to be believed, in 1967, author T.R Hinchcliffe wrote the Pelican book Retro-Futurism with the intention of examining major recurrent themes in mans’ many analogue predictions and prophecies of the future, from inspired fantasy to factually based notions, their cultural & scientific impact, the brilliance (or otherwise) of those ideas, and how they are now faring at the apparent dawning of the, then electronic future. Although a recent neologism, Retrofuturism continues to portray the future, combining recent ideas of nostalgia and retro with the traditions of futurism to explore the tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. This occurs when pre-1960’s futuristic visions by writers, artists and filmmakers are re-examined, refurbished and updated for the present day, offering a nostalgic, counterfactual image of what the future might have been, allowing us to rebuild the imagination and dreams of the past. As we travel deeper into the digital age, are we loosing the ability to look at the future in this romantic way? Past visions of the future were teeming with distinct qualities and weird and wonderful worlds, worlds so far removed from the spirit of today. From Jules Verne’s Novels to Jean Marc Cote’s illustrations, these worlds were intrinsically linked with the technology they portrayed. -

Introduction

Reality Unbound Introduction Introduction Reality Unbound: New Departures in Science Fiction Cinema cience fiction, Jean Baudrillard wrote, “is no longer anywhere, and it is ev- Serywhere.”1 In formulating his conceptualization of simulacra, Baudrillard was struck by the inherent instability of referents, and by proxy the difficulties associated with discerning what is real in the modern world. As we move deeper into the new millennium, Baudrillard’s slippery formulation seems to solidify somehow, as near constant war, financial crises and rising political extremism cloud our assumptions about the contemporary world we have molded. In an age where the language employed by the media, as well as the events it describes, becomes ever more apocalyptic in tone, one might reasonably ponder the rami- fications for sf, which has long held a looking glass up to society, revealing our foibles and reveling in our hunger for advancement and our competing appe- tite for destruction. The 21st century was not supposed to be like this, and yet though still in its infancy, who knows how it will turn out? If we accept that sf provides a shadowy reflection of the times that spawned it, then it is tempting to ask how we and by extension our times will look to future historians? Whilst our worldview has become increasingly unsettled—and a cursory glance at recent sf releases can give the impression that dystopia is the new normal—it would be foolhardy to divorce ourselves from historicity or fall prey to what the British sociologist John Urry described as “an epochal hubris that presumes that one’s own moment is somehow a special moment in transition.”2 Sf cinema has long been cognizant of such considerations of course, and in the midst of chaos it endures. -

101 CC1 Concepts of Fashion

CONCEPT OF FASHION BFA(F)- 101 CC1 Directorate of Distance Education SWAMI VIVEKANAND SUBHARTI UNIVERSITY MEERUT 250005 UTTAR PRADESH SIM MOUDLE DEVELOPED BY: Reviewed by the study Material Assessment Committed Comprising: 1. Dr. N.K.Ahuja, Vice Chancellor Copyright © Publishers Grid No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduce or transmitted or utilized or store in any form or by any means now know or here in after invented, electronic, digital or mechanical. Including, photocopying, scanning, recording or by any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by Publishers Grid and Publishers. and has been obtained by its author from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the publisher and author shall in no event be liable for any errors, omission or damages arising out of this information and specially disclaim and implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Published by: Publishers Grid 4857/24, Ansari Road, Darya ganj, New Delhi-110002. Tel: 9899459633, 7982859204 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Printed by: A3 Digital Press Edition : 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Fashion 5-47 2. Fashion Forecasting 48-69 3. Theories of Fashion, Factors Affecting Fashion 70-96 4. Components of Fashion 97-112 5. Principle of Fashion and Fashion Cycle 113-128 6. Fashion Centres in the World 129-154 7. Study of the Renowned Fashion Designers 155-191 8. Careers in Fashion and Apparel Industry 192-217 9. -

New Practices, New Pedagogies

INNOVATIONS IN ART AND DESIGN NEW PRACTICES NEW PEDAGOGIES a reader EDITED BY MALCOLM MILES SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Printed in Copyright © 2004 …… All rights reserved. No part of this publication of the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the authors for any damage to properly or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. www ISBN ISSN The European League of Institutes of the Arts - ELIA - is an independent organisation of approximately 350 major arts education and training institutions representing the subject disciplines of Architecture, Dance, Design, Media Arts, Fine Art, Music and Theatre from over 45 countries. ELIA represents deans, directors, administrators, artists, teachers and students in the arts in Europe. ELIA is very grateful for support from, among others, The European Community for the support in the budget line 'Support to organisations who promote European culture' and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Published by SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Supported by the European Commission, Socrates Thematic Network ‘Innovation in higher arts education -

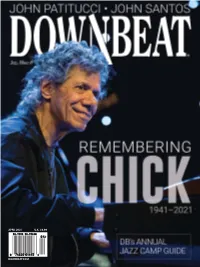

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

“Evolution Takes Love:” Tracing Some Themes of the Solarpunk Genre

“Evolution Takes Love:” Tracing Some Themes of the Solarpunk Genre By William Kees Schuller A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in English Language and Literature in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2019 Copyright © William Kees Schuller, 2019 Schuller i Schuller Abstract This project aims at examining some of the core themes and concerns of Solarpunk, a newly emerging genre. Placing Solarpunk in contrast to one of its nearest literary predecessors, Cyberpunk, I work to unify the disparate definitions of the Solarpunk genre, while examining the ways in which it departs from its Cyberpunk roots while retaining a radical critical mode. By mapping and defining some of Solarpunk’s primary concerns in this way, this project aims to set the groundwork for additional critical work on the Solarpunk genre, providing a foundation from which other scholars may work. Throughout the thesis I work primarily with the four English language Solarpunk anthologies, Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World, Wings of Renewal: A Solarpunk Dragons Anthology, Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation, and Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers. In Chapter One, I examine the interrelationship of social ecology, technological progress, and social progress with questions of community and society, in order to demonstrate the ways in which Solarpunk promotes its ideal, social ecology inspired future. In Chapter Two, I build on the generic interest in progress in order to examine Solarpunk’s optimistic treatment of the posthuman in relation to questions of physiological and capitalist consumption, and fears over the loss of humanity. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Music Director

Program One HundRed TWenTy-FiRST SeASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Tuesday, May 15, 2012, at 1:30 Thursday, May 17, 2012, at 8:00 Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Largo— Allegro molto— Allegretto— Largo— Largo Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto Prelude: Allegro moderato Romanza: Andante sostenuto Finale (Rondo all tedesca): Allegro Gene POkORny IntermISSIon Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto—Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio This evening’s concert is generously sponsored in part by the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation. Wednesday, May 16, 2012, at 6:30 (Afterwork Masterworks, performed with no intermission) Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto in F Minor Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105.9 FM for its generous support as the media sponsor for the Afterwork Masterworks series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentS by PHiLLiP HuSCHeR Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Died August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia. Chamber Symphony for Strings in C minor, op. 110a n the summer of 1960, in just three days, is his Eighth, IShostakovich went to Dresden to and it is one of the most powerful write the score for a new film by the and personal works of twentieth- director Lev Arnshtam.