2020 a Year of Loss Here Are a Few People That Died This Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soundstage! Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper, Steve Stills – Super Session 03.06.09 07:56

SoundStage! Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper, Steve Stills – Super Session 03.06.09 07:56 February 2009 Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper, Steve Stills - Super Session Speakers Corner/Columbia Records CS 9701 Format: LP Originally Released: 1968 Reissue Released: 2008 by Joseph Taylor [email protected] Musical Performance Recording Quality Overall Enjoyment In 1968, Al Kooper had just left Blood Sweat & Tears, the horn band he had started, and was an A&R man at Columbia Records. Guitarist Mike Bloomfield, whom Kooper had played with on Highway 61 Revisited, was also between bands, so Kooper called him up and suggested they jam in the recording studio. Two other musicians, bassist Harvey Brooks and drummer Eddie Hoh, joined them for a marathon nine-hour session (pianist Barry Goldberg sat in on a couple of tracks). The next day, Bloomfield was a no show and Kooper, in a panic, cast about for another guitarist. He was lucky enough to track down Steven Stills, whose band, Buffalo Springfield, had just split up. After another long session, Kooper had enough material to create an album. Super Session, co-credited to Bloomfield, Kooper, and Stills, cost $13,000 to record and became a gold record. Kooper had horn arrangements dubbed onto some of the tunes, but otherwise they were released as originally recorded, except for some editing on a version of Donovan’s "Season of the Witch." Bloomfield is the reason to own the record. His searing guitar work is astonishing, some of the best of his brief career. He plays with focused intensity and a powerful grasp of blues tradition. -

Where to Study Jazz 2019

STUDENT MUSIC GUIDE Where To Study Jazz 2019 JAZZ MEETS CUTTING- EDGE TECHNOLOGY 5 SUPERB SCHOOLS IN SMALLER CITIES NEW ERA AT THE NEW SCHOOL IN NYC NYO JAZZ SPOTLIGHTS YOUNG TALENT Plus: Detailed Listings for 250 Schools! OCTOBER 2018 DOWNBEAT 71 There are numerous jazz ensembles, including a big band, at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. (Photo: Tony Firriolo) Cool perspective: The musicians in NYO Jazz enjoyed the view from onstage at Carnegie Hall. TODD ROSENBERG FIND YOUR FIT FEATURES f you want to pursue a career in jazz, this about programs you might want to check out. 74 THE NEW SCHOOL Iguide is the next step in your journey. Our As you begin researching jazz studies pro- The NYC institution continues to evolve annual Student Music Guide provides essen- grams, keep in mind that the goal is to find one 102 NYO JAZZ tial information on the world of jazz education. that fits your individual needs. Be sure to visit the Youthful ambassadors for jazz At the heart of the guide are detailed listings websites of schools that interest you. We’ve com- of jazz programs at 250 schools. Our listings are piled the most recent information we could gath- 120 FIVE GEMS organized by region, including an International er at press time, but some information might have Excellent jazz programs located in small or medium-size towns section. Throughout the listings, you’ll notice changed, so contact a school representative to get that some schools’ names have a colored banner. detailed, up-to-date information on admissions, 148 HIGH-TECH ED Those schools have placed advertisements in this enrollment, scholarships and campus life. -

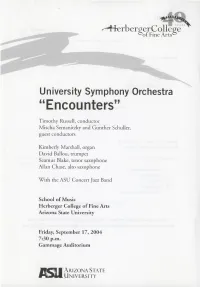

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

Short Takes Jazz News Festival Reviews Jazz Stories Interviews Columns

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC SHORT TAKES JAZZ NEWS FESTIVAL REVIEWS JAZZAMANCA 2020 JAZZ STORIES PATTY WATERS INTERVIEWS PETER BRÖTZMANN BILL CROW CHAD LEFOWITZ-BROWN COLUMNS NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD REVIEWS OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 2 April May June Edition 2020 Ed Schuller (bassist, composer) on GM Recordings My name is Eddy I play the bass A kind of music For the human race And with beauty and grace Let's stay on the case As we look ahead To an uncertain space Peace, Music Love and Life" More info, please visit: www.gmrecordings.com Email: [email protected] GM Recordings, Inc. P.O. Box 894 Wingdale, NY 12594 3 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | APRIL MAY JUNE 2016 L with Wolfgang Köhler In the Land of Irene Kral & Alan Broadbent Live at A-Trane Berlin “The result is so close, so real, so beautiful – we are hooked!” (Barbara) “I came across this unique jazz singer in Berlin. His live record transforms the deeply moving old pieces into the present.” (Album tip in Guido) “As a custodian of tradition, Leuthäuser surprises above all with his flawless intonation – and that even in a live recording!” (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) “Leuthäuser captivates the audience with his adorable, youthful velvet voice.” (JazzThing) distributed by www.monsrecords.de presents Kądziela/Dąbrowski/Kasper Tom Release date: 20th March 2020 For more information please visit our shop: sklep.audiocave.pl or contact us at [email protected] The latest piano trio jazz from Quadrangle Music Jeff Fuller & Friends Round & Round Jeff Fuller, bass • Darren Litzie, piano • Ben Bilello, drums On their 4th CD since 2014, Jeff Fuller & Friends provide engaging original jazz compositions in an intimate trio setting. -

Blood Sweat Tears and When I Die Download Free Blood Sweat Tears and When I Die Download Free

blood sweat tears and when i die download free Blood sweat tears and when i die download free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67addf555e0b7b6b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. BLOOD SWEAT AND TEARS AND WHEN I DIE lyric. Now troubles are many there as deep as a well I can swear there ain't no Heaven but I pray there ain't no hell Swear there ain't no Heaven and I'll pray there ain't no hell but I'll never know by livin' only my dyin' will tell, yes only my dyin' will tell, oh yeah, Only my dyin' will tell. And when I die, and when I'm gone there'll be, one child born, in this world to carry on, to carry on yeah yeah. Give me my freedom for as long as I be All I ask of livin' is to have no chains on me All I ask of livin' is to have no chains on me And all I ask of dyin' is to go natrually, only wanna go naturally Here I go! hey hey Here come the devil right behind look out children, here he come here he come, heyyy. -

The Art of Making Mistakes

The Art of Making Mistakes Misha Alperin Edited by Inna Novosad-Maehlum Music is a creation of the Universe Just like a human being, it reflects God. Real music can be recognized by its soul -- again, like a person. At first sight, music sounds like a language, with its own grammatical and stylistic shades. However, beneath the surface, music is neither style nor grammar. There is a mystery hidden in music -- a mystery that is not immediately obvious. Its mystery and unpredictability are what I am seeking. Misha Alperin Contents Preface (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Introduction Nothing but Improvising Levels of Art Sound Sensitivity Fairytales and Fantasy Music vs Mystery Influential Masters The Paradox: an Improvisation on the 100th Birthday of the genius Richter Keith Jarrett Some thoughts on Garbarek (with the backdrop of jazz) The Master on the Pedagogy of Jazz Improvisation as a Way to Oneself Main Principles of Misha's Teachings through the Eyes of His Students Words from the Teacher to his Students Questions & Answers Creativity: an Interview (with Inna Novosad-Maehlum) About Infant-Prodigies: an Interview (with Marina?) One can Become Music: an Interview (with Carina Prange) Biography (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Upbringing The musician’s search Alperin and Composing Artists vs. Critics Current Years Reflections on the Meaning of Life Our Search for Answers An Explanation About Formality Golden Scorpion Ego Discography Conclusion: The Creative Process (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Preface According to Misha Alperin, human life demands both contemplation and active involvement. In this book, the artist addresses the issues of human identity and belonging, as well as those of the relationship between music and musician. -

«Solo Duo Trio» – Christian Zehnder Di 22.05

«Solo Duo Trio» – Christian Zehnder Di 22.05. / Mi 23.05. / Do 24.05.2018 Mitte Februar 2017 feierte Christian Zehnders Solo «songs from new space mountain» im Gare du Nord seine Uraufführung. Alle drei Premieren-Vorstellungen waren ausverkauft. Die Resonanz auf die Performance war so gross, dass eine Wiederaufnahme schon nach der Premiere im Raum stand. Im Mai 2018 bietet sich nun dem Publikum die Möglichkeit, das Solo «songs from new space mountain» nochmals (oder erstmals) zu sehen – darüber hinaus tritt er auch in zwei Formationen auf, die hier noch kaum bekannt sind: im Duo mit dem Drehorgelspieler Matthias Loibner und im Trio mit dem Hornisten Arkady Shilkloper und dem Pianisten John Wolf Brennan. Di 22.05.18 20:00 «songs from new space mountain» – Christian Zehnder Solo Eine Werkschau und Reise durch den unvergleichlichen Klangkosmos von Christian Zehnder – ein ausserirdischer Heimatabend (Wiederaufnahme) Mit neuen Kompositionen und Werken aus den letzten 20 Jahren führt uns der Stimmenkünstler Christian Zehnder in eine ganz eigenständige, archaische und geradezu ausserirdische Welt der Laute, die völlig ohne Worte auskommt. Der eigenwillige Schweizer Musiker, welcher schon mit dem Duo Stimmhorn die alpine Musik neu aufmischte und Kultstatus geniesst, lässt sich in seiner Vielfalt nicht einordnen. Auch muss man ihn live gesehen haben. Erst dann erschliesst sich sein zwischen Musik, Performance und visueller Ausdruckskraft angelegtes Werk in seiner ganzen Kraft und Faszination. Seit 25 Jahren stehen meine meisten künstlerischen Arbeiten im alpinen Kontext und einer Vision einer neuen klanglichen Utopie der Heimat. Daraus ist bis heute ein sehr persönliches und dennoch breitgefächertes Werk entstanden, welches die menschliche Stimme zwischen alpinem und urbanem Lebensraum zu befragen versucht und in den verschiedensten Disziplinen seine jeweilige Form findet. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Some Notes on John Zorn's Cobra

Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra Author(s): JOHN BRACKETT Source: American Music, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 44-75 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/americanmusic.28.1.0044 . Accessed: 10/12/2013 15:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.30.166 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 15:16:53 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JOHN BRACKETT Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra The year 2009 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of John Zorn’s cele- brated game piece for improvisers, Cobra. Without a doubt, Cobra is Zorn’s most popular and well-known composition and one that has enjoyed remarkable success and innumerable performances all over the world since its premiere in late 1984 at the New York City club, Roulette. Some noteworthy performances of Cobra include those played by a group of jazz journalists and critics, an all-women performance, and a hip-hop ver- sion as well!1 At the same time, Cobra is routinely played by students in colleges and universities all over the world, ensuring that the work will continue to grow and evolve in the years to come. -

ANDREA FERRANTE GIANNI DE BERARDINIS Con Una Sconcertante Puntualità Capace Di Superare Ogni Più Rosea Speranza, Arriva MAT2020 Di Aprile

MAT2020 - Anno II - n°15 - 04/14 CAMEL GLAD TREE SOPHYA BACCINI ANDREA FERRANTE GIANNI DE BERARDINIS Con una sconcertante puntualità capace di superare ogni più rosea speranza, arriva MAT2020 di aprile. Qualche nuova entrata tra i collaboratori occasionali porta una ventata di opinioni fresche, anche se chi le propone ha esperienza da vendere, come il giovane Jacopo Muneratti, che MAT 2020 - MusicArTeam racconta... si addentra nel mondo di Captain Beefheart, e il saggista Innocenzo Alfano, che ci racconta [email protected] l’ultimo libro di Mox Cristadoro, I cento migliori dischi del progressive italiano. Angelo De Negri Ritorna Claudio Milano che descrive l’album di OTEME, mentre Gianmaria Consiglio propone General Manager and Web Designer l’intervista realizzata con Sophya Baccini. Athos Enrile A proposito di botta e risposta, è con grande piacere che ritroviamo un mito televisivo di 1st Vice General Manager and Chief Editor qualche anno fa, più che mai sul campo, Gianni De Berardinis, così come va sottolineato lo Massimo ‘Max’ Pacini scambio di battute con Andrea Ferrante. 2nd Vice General Manager, Chief Editor and Webmaster Marta Benedetti, Paolo ‘Revo’ Revello La sezione live è ridotta, ma di estrema qualità, per effetto del racconto di Alberto Sgarlato Administration del concerto dei Camel, che mantiene comunque viva la sua rubrica mensile. Web Journalists: Innocenzo Alfano, Gianmaria Consiglio, Claudio Milano, Jacopo Muneratti, Tra quelli che non mollano mai possiamo ancora inserire Mauro Selis, titolare del “Prog del Fabrizio Poggi, Gianni Sapia, Mauro Selis, Alberto Sgarlato, Riccardo Storti. Sud America” e della sezione “Psicology”, Riccardo Storti, che rivisita Alberto Radius, Fabri- zio Poggi, titolare dell’angolo blues, e Gianni Sapia che sviscera l’opera prima di Marcello Faranna. -

Keeping the Tradition by Marilyn Lester © 2 0 1 J a C K V

AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM P EE ING TK THE R N ADITIO DARCY ROBERTA JAMES RICKY JOE GAMBARINI ARGUE FORD SHEPLEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East AUGUST 2018—ISSUE 196 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : ROBERTA GAMBARINI 6 by ori dagan [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : darcy james argue 7 by george grella General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : preservation hall jazz band 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ricky ford by russ musto Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : joe shepley 10 by anders griffen [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : weekertoft by stuart broomer US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 31 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Event Calendar 32 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Mathieu Bélanger, Marco Cangiano, Ori Dagan, George Grella, George Kanzler, Annie Murnighan Contributing Photographers “Tradition!” bellowed Chaim Topol as Tevye the milkman in Fiddler on the Roof.