Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Integrated Approach for the Evaluation of Technological Hazard Impacts on Air Quality: the Case of the Val D’Agri Oil/Gas Plant” by M

Open Access Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., 2, C912–C913, 2014 Natural Hazards www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/2/C912/2014/ and Earth System © Author(s) 2014. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribute 3.0 License. Sciences Discussions Interactive comment on “An integrated approach for the evaluation of technological hazard impacts on air quality: the case of the Val d’Agri oil/gas plant” by M. Calvello et al. M. Calvello et al. [email protected] Received and published: 29 May 2014 On behalf of all co-authors, I wish to thank Referee for the comments. The Val d’Agri area (Basilicata region - southern Italy) is a peculiar site due to the coexistence of the biggest on-shore reservoir of Western Europe with a large oil/gas pre-treatment plant (COVA) on one side and a populated area with several small towns, agricultural activ- ities with valuable crops, woods and natural parks on the other. To assess the risks associated to the oil/gas exploration and pre-treatment activities on the local air quality and human health, a dedicated network has been designed and realized with five mon- itoring stations covering the area in a cross-shaped setting. The peculiarity and novelty C912 of such a network is its density near the site and its capability to follow near-real time variation of plant-specific pollutants so that, at our knowledge, this is the first air quality network which provides continuous concentration measurements of so many pollu- tants in a such small area. -

Magic and the Supernatural

Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Magic and the Supernatural At the Interface Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E An At the Interface research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/at-the-interface/ The Evil Hub ‘Magic and the Supernatural’ 2012 Magic and the Supernatural Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-095-5 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table of Contents Preface vii Scott Hendrix PART 1 Philosophy, Religion and Magic Magic and Practical Agency 3 Brian Feltham Art, Love and Magic in Marsilio Ficino’s De Amore 9 Juan Pablo Maggioti The Jinn: An Equivalent to Evil in 20th Century 15 Arabian Nights and Days Orchida Ismail and Lamya Ramadan PART 2 Magic and History Rational Astrology and Empiricism, From Pico to Galileo 23 Scott E. -

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

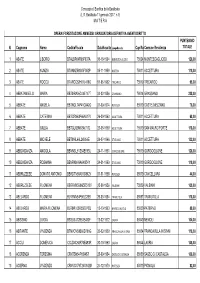

1-Graduatoria Definitiva Operai Aventi Diritto

Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. Basilicata 11 gennaio 2017, n.1) M A T E R A OPERAI FORESTAZIONE AMMESSI: GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA AVENTI DIRITTO PUNTEGGIO N. Cognome Nome CodiceFiscale DataNascita LuogoNascita Cap ResidenzaComune Residenza TOTALE 1 ABATE LIBORIO BTALBR64R06F637A 06-10-1964 MONTESCAGLIOSO 75024 MONTESCAGLIOSO 128,00 2 ABATE NUNZIA BTANNZ59S45F052P 05-11-1959 MATERA 75011 ACCETTURA 118,00 3 ABATE ROCCO BTARCC62H01L418O 01-06-1962 TRICARICO 75019 TRICARICO 98,00 4 ABBATANGELO MARIA BBTMRA56C44E147T 04-03-1956 GRASSANO 75014 GRASSANO 228,00 5 ABBATE ANGELA BBTNGL74P41G942O 01-09-1974 POTENZA 85010 CASTELMEZZANO 76,00 6 ABBATE CATERINA BBTCRN63P66A017V 26-09-1963 ACCETTURA 75011 ACCETTURA 68,00 7 ABBATE GIULIA BBTGLI69M63A017D 23-08-1969 ACCETTURA 75010 SAN MAURO FORTE 118,00 8 ABBATE MICHELE BBTMHL66L24I954E 24-07-1966 STIGLIANO 75011 ACCETTURA 132,00 9 ABBONDANZA ANGIOLA BBNNGL61S64E093U 24-11-1961 GORGOGLIONE 75010 GORGOGLIONE 128,00 10 ABBONDANZA ROSANNA BBNRNN69A64I954Y 24-01-1969 STIGLIANO 75010 GORGOGLIONE 118,00 11 ABBRUZZESE DONATO ANTONIO BBRDTN68A01G942V 01-01-1968 POTENZA 85010 CANCELLARA 44,00 12 ABBRUZZESE FILOMENA BBRFMN56M65D513V 25-08-1956 VALSINNI 75029 VALSINNI 108,00 13 ABELARDO FILOMENA BLRFMN54P66L326B 26-09-1954 TRAMUTOLA 85057 TRAMUTOLA 118,00 14 ABELARDO MARIA FILOMENA BLRMFL63R55E976Q 15-10-1963 MARSICO NUOVO 85050 PATERNO 88,00 15 ABISSINO LUIGIA BSSLGU72B53E483F 13-02-1972 LAURIA 85040 NEMOLI 104,00 16 ABITANTE VINCENZA BTNVCN59B66D766G 26-02-1959 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 85034 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 118,00 17 ACCILI DOMENICA CCLDNC60R70E483R 30-10-1960 LAURIA 85044 LAURIA 148,00 18 ACERENZA TERESINA CRNTSN54P65I457I 25-09-1954 SASSO DI CASTALDA 85050 SASSO DI CASTALDA 108,00 19 ACIERNO VINCENZO CRNVCN79T24G942M 24-12-1979 POTENZA 85010 PIGNOLA 82,00 Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. -

Drought Mitigation Using Operative Indicators in Complex Water Systems Giovanni M

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive 4th International Congress on Environmental International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software - Barcelona, Catalonia, Modelling and Software Spain - July 2008 Jul 1st, 12:00 AM Drought Mitigation using Operative Indicators in Complex Water Systems Giovanni M. Sechi Andrea Sulis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/iemssconference Sechi, Giovanni M. and Sulis, Andrea, "Drought Mitigation using Operative Indicators in Complex Water Systems" (2008). International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software. 205. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/iemssconference/2008/all/205 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil and Environmental Engineering at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. iEMSs 2008: International Congress on Environmental Modelling and Software Integrating Sciences and Information Technology for Environmental Assessment and Decision Making 4th Biennial Meeting of iEMSs, http://www.iemss.org/iemss2008/index.php?n=Main.Proceedings M. Sànchez-Marrè, J. Béjar, J. Comas, A. Rizzoli and G. Guariso (Eds.) International Environmental Modelling and Software Society (iEMSs), 2008 Drought Mitigation using Operative Indicators in Complex Water Systems G.M. Sechia and A. Sulisb a Hydraulic Sector, Dept. of Land Engineering, University of Cagliari, Italy ([email protected]) b Hydraulic Sector, Dept. of Land Engineering, University of Cagliari, Italy ([email protected]) Abstract: The definition of an effective link between drought indicators and drought mitigation measures in complex water systems is a tricky problem. -

Comune Di Calvello (Potenza) Regolamento Urbanistico Relazione 1

Comune di Calvello (Potenza) 1 Regolamento urbanistico Relazione 1. INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE Il Comune di Calvello è collocato in una zona interna della Provincia di Potenza. Ha un territorio esteso per 105 kmq con una densità territoriale di 22 abitanti per Kmq. Confina a nord e a nord-est con i Comuni di Abriola e Anzi, ad est con Laurenzana, a sud con Viggiano, a sud-est con Marsicovetere e a sud-ovest con Marsiconuovo. Fa parte della Comunità Montana Alto Sauro Calastra e dell’area PIT dell’Alto Basento. I collegamenti principali sono assicurati dalle strade provinciali Potenza- Pignola-Abriola-Calvello, Calvello Marsicovetere e Calvello –Laurenzana – Camastra- SS Basentana. Quest’ultima arteria, collegando il paese con la Basentana, rappresenta il più agevole collegamento con la viabilità regionale ed extra regionale. Le altre strade assumono un valore più propriamente interno, anche se, i recenti sviluppi legati allo sfruttamento petrolifero, hanno collocato la viabilità di collegamento con la Val d’Agri su un piano di grande importanza. 1.a Le prospettive territoriali introdotte dal PSSE della Comunità Montana Alto Sauro Camastra Il PSSE della Comunità Montana Alto Sauro Camastra pone, tra i suoi obiettivi, quello del completamento della Saurina rispetto al quale si stanno discutendo diverse opzioni. Il Piano sottolinea che quale che sia la scelta progettuale definitiva della Saurina, il tratto di S.P. 32 da Bivio Calvello alla Saurina stessa andrà comunque migliorato, divenendo bretella di collegamento fra la Saurina, il nodo Camastra, Calvello ed Abriola. Il Piano Comune di Calvello (Potenza) 2 Regolamento urbanistico Relazione medesimo individua, tra gli assi di secondo livello, il collegamento Camastra – Abriola – Pierfaone, di cui sono necessari ultimazione e miglioramenti. -

Rotonda Provincia Di Potenza

Comune di Rotonda Provincia di Potenza Via Roma, 56 – 85048 – Rotonda (PZ) – Tel. +390973661005 – Fax: +390973661006 Sito Web: www.comune.rotonda.pz.it E-mail: [email protected] Ufficio di Servizio Sociale COMUNICAZIONE ALLA CITTADINANZA COMUNICAZIONE ALLA CITTADINANZA A valere sull’”AP per la presentazione di proposte progettuali a sostegno della domiciliarità e dell’autogoverno per persone con limitazioni nell’autonomia”, con il sostegno del PO FSE Basilicata 2014-2020- azione 9.3.6, sarà attivato nell’Ambito Socio Territoriale Lagonegrese Pollino il seguente progetto rivolto alla popolazione anziana ultrasettantacinquenne TITOLO PROGETTO: ANZIANI MENO SOLI SOGGETTO CAPOFILA: “ARCA” SOC. COOP. SOCIALE PARTNER A LIVELLO OPERATIVO: AUSER – CASTELLUCCIO INFERIORE ASS. VOL. “AMICI DELL’ARCA” PARTNER SOSTEGNO E GARANZIA: COMUNE DI CASTELLUCCIO INFERIORE AVVISO PUBBLICO PER LA PRESENTAZIONE DI PROPOSTE PROGETTUALI A SOSTEGNO DELLA DOMICILIARITA’ Regione Basilicata Dipartimento Politiche della Persona 1 Ufficio Terzo Settore Via Vincenzo Verrastro, 9 - 85100 Potenza web: www.europa.basilicata.it/fse COMUNE DI CASTELLUCCIO SUPERIORE COMUNE DI FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI COMUNE DI LATRONICO COMUNE DI ROTONDA COMUNE DI VIGGIANELLO I progetti in fase di attivazione sono articolati in azioni personalizzate tese a: a) Sostenere la domiciliarità, la permanenza nel proprio luogo di vita e di relazioni; b) Supportare l’accesso ai servizi socio-culturali per anziani, soprattutto per quelli che per condizione economica e/o relazionale negativa sono a rischio di solitudini involontarie; c) Promuovere un processo di presa in carico secondo modalità innovative ed espressive che valorizzino anche l’aspetto ludico e animativo per un miglioramento della qualità di vita; d) Consolidare reti territoriali a sostegno della popolazione anziana a rischio di esclusione sociale attraverso lo sviluppo di luoghi di incontro per la vita di relazione. -

Meike Weijtmans S4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: Dr

Weijtmans, s4235797/1 Meike Weijtmans s4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: dr. Chris Cusack Examiner: dr. L.S. Chardonnens August 15, 2018 The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend M.A.S. Weijtmans BA Thesis August 15, 2018 Weijtmans, s4235797/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: dr. Chris Cusack, dr. L.S. Chardonnens Title of document: The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: August 15, 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Meike Weijtmans Student number: s4235797 Weijtmans, s4235797/3 Abstract Celtic culture has always been a source of interest in contemporary popular culture, as it has been in the past; Greek and Roman writers painted the Celts as barbaric and uncivilised peoples, but were impressed with their religion and mythology. The Celtic revival period gave birth to the paradox that still defines the Celtic image to this day, namely that the rurality, simplicity and spirituality of the Celts was to be admired, but that they were uncivilised, irrational and wild at the same time. Recent debates surround the concepts of “Celt”, “Celticity” and “Celtic” are also discussed in this thesis. The first part of this thesis focuses on Celtic history and culture, as well as the complexities surrounding the terminology and the construction of the Celtic image over the centuries. This main body of the thesis analyses the way Celtic elements in contemporary adaptations of the Arthurian narrative form the modern Celtic image. -

REGIONE BASILICATA Provincia Di Potenza COMUNI DI FORENZA E

REGIONE BASILICATA Provincia di Potenza COMUNI DI FORENZA E MASCHITO PROGETTO PARCO EOLICO FORENZA – MASCHITO POTENZIAMENTO IMPIANTO DI FORENZA INTEGRAZIONI COMMITTENTE PROGETTISTA OGGETTO DELL’ELABORATO C0004891 - Integrazioni richieste dalla Regione Basilicata con prot. n. 0162576/2019 Rev. 00 Data di emissione 27/03/2020 RAPPORTO USO RISERVATO APPROVATO C0004891 Cliente ERG Power Generation S.p.A. Oggetto Parco eolico Forenza-Maschito Potenziamento impianto di Forenza Integrazioni richieste dalla Regione Basilicata con prot. n. 0162576/2019 Ordine n. 4700026705 del 14.11.2018 - C0004846 Note A1300002442 – Lettera trasmissione C0004896 USO RISERVATO La parziale riproduzione di questo documento è permessa solo con l'autorizzazione scritta del CESI. PAD C0004891 (2749116) - N. pagine 58 N. pagine fuori testo 14 Allegati Data 27/03/2020 4 Elaborato F. Carnevale,SCE - Ghidelli M. Ghilardi, Franco, ESCG. Barbieri, - Ghilardi C. Montanelli,Marina, SCE F. - Ghidelli Barbieri Giorgio, C0004891 114977 AUT C0004891 114978 AUT C0004891 114979 AUT SCE - Montanelli Cesare, SCE - Carnevale Francesco Verificato PertotC0004891 115002 AUT C0004891 3194063 AUT Verificato ESC - Pertot Cesare C0004891 3840 VER Mod. RAPP v. 1 Approvato Ghilardi, Carnevale Approvato ESC - Ghilardi Marina (Project Manager) C0004891 114978 APP CESI S.p.A. Pag. 1/58 Via Rubattino 54 Capitale sociale € 8.550.000 interamente versato I-20134 Milano - Italy C.F. e numero iscrizione Reg. Imprese di Milano 00793580150 Tel: +39 02 21251 P.I. IT00793580150 Fax: +39 02 21255440 N. R.E.A. 429222 e-mail: [email protected] www.cesi.it © Copyright 2020 by CESI. All rights reserved RAPPORTO USO RISERVATO APPROVATO C0004891 Indice 1 PREMESSA ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 RICHIESTA 1 – ISTANZA PER AUTORIZZAZIONE PAESAGGISTICA ................................................ -

Comune Di Ripacandida

REGIONE BASILICATA PROVINCIA DI POTENZA COMUNE DI RIPACANDIDA PIANO DI ASSESTAMENTO FORESTALE DEI BENI SILVO-PASTORALI Periodo di validità 2019 – 2028 RELAZIONE TECNICA Associazione temporanea di professionisti Il Capogruppo I Componenti Dottore forestale Vito Mancusi Dottore forestale Giovanni Luca Carrieri Dottore forestale Donatello P. Mininni Dottore forestale Angelo Rita 2 Sommario PREMESSA ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1. L’AMBIENTE ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Inquadramento geografico ..................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Caratteristiche geologiche e geomorfologiche dell’area ....................................................... 7 1.3 Caratteri pedologici ............................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Rete idrografica ................................................................................................................... 10 1.5 Aspetti climatici .................................................................................................................. 10 1.6 Vegetazione ......................................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Aspetti faunistici................................................................................................................. -

CV Arch. Lorenzo Di Lucchio

Curriculum Vitae Europass Informazioni personali Nome(i) / Cognome(i) Lorenzo Di Lucchio Indirizzo(i) 40, Via Ugo La Malfa, 85028, Rionero in Vulture, Italia Telefono(i) 0972723792 3515881987 Fax 0972723792 E-mail _PEC [email protected] Email _ [email protected] Cittadinanza Italiana Data di nascita 25 settembre 1969 Sesso Maschile Esperienza professionale 2017 Responsabile del Servizio Urbanistica del Comune di Rionero in Vulture (Pz) (dal 2008) Comune di Rionero in Vulture Via Raffaele Ciasca, 8 - Rionero in Vulture (Pz) 2015 Redazione del Regolamento Urbanistico del Comune di Melfi (Pz) Comune di Melfi Piazza Pasquale festa campanile, 1 - Melfi (Pz) 2010 Redazione del Regolamento Urbanistico del Comune di Rionero in Vulture (Pz) Comune di Rionero in Vulture Via Raffaele Ciasca, 8 - Rionero in Vulture (Pz) 2006 dal 1.06.2006 – è dipendente a tempo indeterminato del Comune di Rionero in Vulture in posizione di lavoro corrispondente alla categoria D3 del CCNL Regioni e Autonomie Locali – Titolare di P.O.. 2002 Redazione della fase analitica e valutativa del Piano Strutturale Provinciale della Provincia di Potenza (L.R. 23/99). Provincia di Potenza Piazza Prefettura, 1 – Potenza 1993-2003 ha partecipato come collaboratore ai seguenti incarichi Progetto di Piano Regolatore Generale e Regolamento Edilizio del Comune di Melfi (PZ) (Progettisti incaricati Prof. Arch. Leonardo Benevolo e Paride Giustino Caputi) Pubblicato su Casabella n. 611, aprile 1994, Urbanistica 102 /94 e Il Manifesto 7/1/97; Coordinamento per la -

Elenco Non Ancora Collocati

Elenco non ancora collocat Comune della scuola di Progr Cognome Nome appartenenza 1 Amore Nadia MELFI 2 Accardo Stefania MELFI 3 Addante Donato GENZANO DI LUCANIA 4 Alfano Vincenzo MELFI 5 Armiento Maria MELFI 6 Attubato Antonia LAVELLO 7 Balletta Orsola RIONERO IN VULTURE 8 BECUCCI CLAUDIA BARILE 9 Bellusci Anna VENOSA 10 BIANCHINO STEFANIA RIONERO IN VULTURE 11 Botte Gennaro Edilio MELFI 12 Bufano Anna MELFI 13 Caglia Cristiana VENOSA 14 CARBUTTO PRINCIPIA LAVELLO 15 Cassetta Maria Assunta RIONERO IN VULTURE 16 CECERE ANNA MELFI 17 Cilenti Maria Rosaria Palma MELFI 18 CORBO ENZO RIONERO IN VULTURE 19 Croce Angela MELFI 20 D'ADAMO ROSSELLA RIONERO IN VULTURE 21 D'Amato Anna LAVELLO 22 D'ANDREA SONIA MELFI 23 D'Angelo Rosa MELFI 24 De Pari Anna Maria MELFI 25 Delle Donne Teresa PALAZZO SAN GERVASIO 26 Di Benga Daniela MELFI 27 Di Lonardo Anna BARILE 28 DI LORENZO PATRIZIA MELFI 29 Ferrenti Teodoro VENOSA 30 FESTA ROSA PALAZZO SAN GERVASIO 31 fusco margherita VENOSA 32 Giansanti Michelina MELFI 33 Graziano Rosaria RIONERO IN VULTURE 34 GRIECO ROSA BARILE 35 Grieco Sonia SAN FELE 36 Gruosso Maria LAVELLO 37 Imbriano Ida RIONERO IN VULTURE 38 Lagala Maria LETIZIA VENOSA 39 Lamorte Gina MELFI 40 Libutti Maria Lucia MELFI 41 Lisena Francesco LAVELLO 42 Lorusso Mariangela MELFI 43 LOZUPONE VITO MICHELE RIONERO IN VULTURE 44 Manella Maria Rosaria LAVELLO 45 MASTRAPASQUA PIETRO LAVELLO 46 MAURIELLO GIACOMO LAVELLO 47 Miglionico Milena ATELLA 48 miranda ernesto VENOSA 49 Modugno Aldo MELFI Elenco non ancora collocat 50 MONTICELLI CAPUTO SILVIA