Downloads, and Sharing Via the Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing Musicians Making New Sound Worlds

PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Compiled by Orlando Musumeci PREPARING MUSICIANS MAKING NEW SOUND WORLDS new musicians new musics new processes Proceedings of the SEMINAR of the COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya – Barcelona – SPAIN 5-9 JULY 2004 Compiled by Orlando Musumeci Published by the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya Catalan texts translated by Mariam Chaib Babou (except for Rosset i Llobet) Spanish texts translated by Orlando Musumeci (except for Estrada, Mauleón and Rosset i Llobet) Copyright © ISME. All rights reserved. Requests for reprints should be sent to: International Society for Music Education ISME International Office P.O. Box 909 Nedlands 6909, WA, Australia T ++61-(0)8-9386 2654 / F ++61-(0)8-9386-2658 [email protected] ISBN: 0-9752063-2-X ISME COMMISSION FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN DIANA BLOM [email protected] University of Western Sydney – AUSTRALIA PHILEMON MANATSA [email protected] Morgan Zintec – ZIMBABWE ORLANDO MUSUMECI (Chair) [email protected] Institute of Education – University of London – UK Universidad de Quilmes – Universidad de Buenos Aires – Conservatorio Alberto Ginastera – ARGENTINA INOK PAEK [email protected] University of Sheffield – UK VIGGO PETTERSEN [email protected] Stavanger University College – NORWAY SUSAN WHARTON CONKLING [email protected] Eastman School of Music – USA GRAHAM BARTLE (Special Advisor) [email protected] -

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

Cold Chisel to Roll out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History!

Cold Chisel to Roll Out the Biggest Archival Release in Australian Music History! 56 New and Rare Recordings and 3 Hours of Previously Unreleased Live Video Footage to be Unveiled! Sydney, Australia - Under total media embargo until 4.00pm EST, Monday, 27 June, 2011 --------------------------------------------------------------- 22 July, 2011 will be a memorable day for Cold Chisel fans. After two years of exhaustively excavating the band's archives, 22 July will see both the first- ever digital release of Cold Chisel’s classic catalogue as well as brand new deluxe reissues of all of their CDs. All of the band's music has been remastered so the sound quality is better than ever and state of the art CD packaging has restored the original LP visuals. In addition, the releases will also include previously unseen photos and liner notes. Most importantly, these releases will unleash a motherlode of previously unreleased sound and vision by this classic Australian band. Cold Chisel is without peer in the history of Australian music. It’s therefore only fitting that this reissue program is equally peerless. While many major international artists have revamped their classic works for the 21st century, no Australian artist has ever prepared such a significant roll out of their catalogue as this, with its specialised focus on the digital platform and the traditional CD platform. The digital release includes 56 Cold Chisel recordings that have either never been released or have not been available for more than 15 years. These include: A “Live At -

10% Off Free for Seniors Monthly

Trust us to care for your beloved pets at home! 10% OFF FREE FOR SENIORS MONTHLY Wildflower Wonder Tour 29 AUG - 1 SEP 4 DAYS $1120pp Dalwallinu, Cervantes, Geraldton 7 Happy 25th Anniversary Have a Go News 200 ince ews s a Go N DA Have Y TOUR tising in S EXTENDED TOURS CHARTERS Adver Phone Jenny 0400 611 840 1300 233 556 [email protected] [email protected] www.royalgalatours.com.au www.houseandpetsitters.com.au LIFESTYLE OPTIONS FOR THE MATURE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN VOLUME 25 NO. 12 ISSUE NO. 292 JULY 2016 Special 25th anniversary WRAP See the special message from Hon Tony Simpson MLA Minister for Local Government; Community Services; Seniors and Volunteering; Youth WIN WIN WIN FABULOUS PRIZES FROM TO CELEBRATE THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION Visit www.haveagonews.com.au Like us on facebook SUPPORTING SENIORS’ RECREATION COUNCIL OF WA (INC) ����������� HAGN#153/292 Murray Kings 30 Year <ŝŶŐƐdŽƵƌƐΘdƌĂǀĞů Princess ĞůĞďƌĂƟŽŶ ŽŶŐƌĂƚƵůĂƚĞ Cruise Including My Fair Lady 9 DAYS, 13 TO 21 OCTOBER 2016 6 DAYS, 4 TO 9 OCTOBER 2016 TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Visit the Barossa Valley Enjoy an TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Tour of Vaucluse House Aussie BBQ on the banks of the Murray River Dance and Guided tour and morning tea at Royal Botanic enjoy dinner at the Captain’s dinner Watch the sun set Gardens Sydney Entry and morning tea at ŽŶƚŚĞŝƌϮϱzĞĂƌŶŶŝǀĞƌƐĂƌLJ each night on the Murray River Play bridge and other TOUR COST PER PERSON Everglades Gardens, Leura Visit the Leura Garden Together, we enrich the lives of games on-board the Murray Princess ^ƉĞŶĚƟŵĞŝŶƚŚĞ &ĞƐƟǀĂů Tour of the Sydney Opera House * quaint German village of Hahndorf . -

Top 200 Most Requested Songs

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2013 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 3 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 8 Psy Gangnam Style 9 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 10 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 11 B-52's Love Shack 12 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 13 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 14 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 15 V.I.C. Wobble 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Beatles Twist And Shout 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Feat. Wanz Thrift Shop 20 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 21 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 22 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 23 Pink Raise Your Glass 24 Outkast Hey Ya! 25 Isley Brothers Shout 26 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 27 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 28 Mars, Bruno Marry You 29 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 30 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 31 Lumineers Ho Hey 32 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Sister Sledge We Are Family 35 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 36 Temptations My Girl 37 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 38 Train Marry Me 39 Kool & The Gang Celebration 40 Daft Punk Feat. -

Document Title

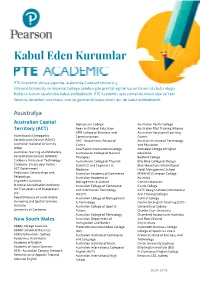

Kabul Eden Kurumlar PTE Academic dünya çapında, aralarında Stanford University, Harvard University ve Imperial College London gibi prestijli eğitim kurumlarının da bulunduğu, binlerce kurum tarafından kabul edilmektedir. PTE Academic aynı zamanda Avustralya ve Yeni Zelanda devletleri tarafından vize ve göçmenlik başvuruları için de kabul edilmektedir. Avustralya Australian Capital Alphacrucis College Australian Pacific College Territory (ACT) Apex Institute of Education Australian Pilot Training Alliance APM College of Business and Australian Vocational Learning Australasian Osteopathic Communication Centre Accreditation Council (AOAC) ARC - Accountants Resource Australis Institute of Technology Australian National University Centre and Education (ANU) Asia Pacific International College Avondale College of Higher Australian Nursing and Midwifery Australasian College of Natural Education Accreditation Council (ANMAC) Therapies Bedford College Canberra Institute of Technology Australasian College of Physical Billy Blue College of Design Canberra. Create your future - Scientists and Engineers in Blue Mountains International ACT Government Medicine Hotel Management School Endeavour Scholarships and Australian Academy of Commerce (BMIHMS) Campion College Fellowships Australian Academy of Australia Engineers Australia Management & Science Carrick Education National Accreditation Authority Australian College of Commerce Castle College for Translators and Interpreters and Information Technology CATC Design School (Commercial Ltd (ACCIT) Arts Training -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020

Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (a company limited by guarantee) and its controlled entity ABN 42 000 016 099 Annual Financial Report 30 June 2020 Australasian Performing Right Association Limited and its controlled entity Annual Report 30 June 2020 Directors’ report For the year ended 30 June 2020 The Directors present their report together with the financial statements of the consolidated entity, being the Australasian Performing Right Association Limited (Company) and its controlled entity, for the financial year ended 30 June and the independent auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of the Company at any time during or since the financial year are: Jenny Morris OAM, MNZM Non-executive Writer Director since 1995 and Chair of the Board A writer member of APRA since 1983, Jenny has been a music writer, performer and recording artist since 1980 with three top 5 and four top 20 singles in Australia and similar success in New Zealand. Jenny has recorded nine albums gaining gold, platinum and multi-platinum status in the process and won back to back ARIA awards for best female vocalist. Jenny was inducted into the NZ Music Hall of Fame in 2018. Jenny is also a non-executive director and passionate supporter of Nordoff Robbins Music Therapy Australia. Jenny presents their biennial ‘Art of Music’ gala event, which raises significant and much needed funds for the charity. Bob Aird Non-executive Publisher Director from 1989 to 2019 Bob recently retired from his position as Managing Director of Universal Music Publishing Pty Limited, Universal Music Publishing Group Pty Ltd, Universal/MCA Publishing Pty Limited, Essex Music of Australia Pty Limited and Cromwell Music of Australia Pty Limited which he held for 16 years. -

M-Phazes | Primary Wave Music

M- PHAZES facebook.com/mphazes instagram.com/mphazes soundcloud.com/mphazes open.spotify.com/playlist/6IKV6azwCL8GfqVZFsdDfn M-Phazes is an Aussie-born producer based in LA. He has produced records for Logic, Demi Lovato, Madonna, Eminem, Kehlani, Zara Larsson, Remi Wolf, Kiiara, Noah Cyrus, and Cautious Clay. He produced and wrote Eminem’s “Bad Guy” off 2015’s Grammy Winner for Best Rap Album of the Year “ The Marshall Mathers LP 2.” He produced and wrote “Sober” by Demi Lovato, “playinwitme” by KYLE ft. Kehlani, “Adore” by Amy Shark, “I Got So High That I Found Jesus” by Noah Cyrus, and “Painkiller” by Ruel ft Denzel Curry. M-Phazes is into developing artists and collaborates heavy with other producers. He developed and produced Kimbra, KYLE, Amy Shark, and Ruel before they broke. He put his energy into Ruel beginning at age 13 and guided him to RCA. M-Phazes produced Amy Shark’s successful songs including “Love Songs Aint for Us” cowritten by Ed Sheeran. He worked extensively with KYLE before he broke and remains one of his main producers. In 2017, Phazes was nominated for Producer of the Year at the APRA Awards alongside Flume. In 2018 he won 5 ARIA awards including Producer of the Year. His recent releases are with Remi Wolf, VanJess, and Kiiara. Cautious Clay, Keith Urban, Travis Barker, Nas, Pusha T, Anne-Marie, Kehlani, Alison Wonderland, Lupe Fiasco, Alessia Cara, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Teyana Taylor, Pink Sweat$, and Wale have all featured on tracks M-Phazes produced. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Come Over VanJess Homegrown (Deluxe) Keep Cool/RCA P,W 2021 Remi Wolf Sexy Villain Single Island P,W 2021 Yung Bae ft. -

Australian Story: Raise Your Voice

RELEASED: Wednesday, October 7, 2015 Australian Story: Raise Your Voice Airs Monday, October 12 at 8pm on ABC & introduced by Hugo Weaving What would you do if you lost something that’s been the essence of you for most of your life? Something that’s given you joy, a vocation, even fame – and then one day it starts slipping away... For singer Jenny Morris, that question recently became very real. The ARIA Award-winning performer makes a dramatic personal revelation in this week’s episode of Australian Story. She has been diagnosed with a life-changing medical condition. “It was evident that Jenny wanted to just play it down until she knew what was going on,” says her sister, singer Shanley Del. Jenny Morris first found success with New Zealand band The Crocodiles, before relocating to Australia in the early 1980s. After recording and touring with INXS as a backing singer, she established a successful solo career with hits such as Break in the Weather and She has to be Loved, as well as performing with Prince and Paul McCartney. About 10 years ago, she noticed something going on with her voice. “I’ve never talked about it publicly, and I think putting the word out there is going to give a sense of relief. That’s why I’m doing Australian Story because I think if you want to know what’s what, look at this program. Then I don’t have to explain it,” she says. KNOW THE STORY – AUSTRALIAN STORY Join the conversation: #AustralianStory Producer: Ben Cheshire Executive Producer: Deb Masters ___________________________________________________________________ For further information, please contact: Chris Chamberlin | News Publicist | ABC TV Publicity 02 8333 2154 / 0404 075 749 / [email protected] @popculturechris . -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

2017 Songbooks (Autosaved).Xlsx

THE ARAOKE K PARTY NIGHT Song Title Emancip8 Entertainment & Wedding Sounds www.thekaraokepartynight.com.au Song Title Artist Code 1 Mortin Solveig & Same White 21412 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 20606 1999 Prince 20517 #9 dream John Lennon 8417 1 + 1 Beyonce 9298 1 2 3 One Two Three Len Barry 4616 1 2 step Missy Elliot 7538 1 Thing Amerie 20018 1, 2 Step Ciara ft. Missy Elliott 20125 10 Million People Example 10203 100 Years Five For Fighting 4453 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 6117 1000 miles away Hoodoo Gurus 7921 1000 stars natalie bathing 8588 12:51 Strokes 4329 15 FEET OF SNOW Johnny Diesel 9015 17 Forever metro station 8699 18 and life skid row 7664 18 Till i die Bryan Adams 8065 1959 Lee Kernagan 9145 1973 James Blunt 8159 1983 Neon Trees 9216 2 Become 1 Jewel 4454 2 FACED LOUISE 8973 2 hearts Kylie Minogue 8206 20 good reasons thirsty merc 9696 21 Guns Greenday 8643 21 questions 50 Cent 9407 21st century breakdown Greenday 8718 21st century girl willow smith 9204 22 Taylor Swift 9933 22 (twenty-two) Lily Allen 8700 22 steps damien leith 8161 24K MAGIC BRUNO MARS 21533 3 (one two three) Britney Spears 8668 3 am Matchbox 20 3861 3 words cheryl cole f. will 8747 4 ever Veronicas 7494 4 Minutes Madonna & JT 8284 4,003,221 Tears From Now Judy Stone 20347 45 Shinedown 4330 48 Special Suzi Quattro 9756 4TH OF JULY SHOOTER JENNINGS 21195 5, 6, 7, 8. steps 8789 50 50 Lemar 20381 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 1805 50 ways to say Goodbye Train 9873 500 miles Proclaimers 7209 6 WORDS WRETCH 32 21068 7 11 BEYONCE 21041 7 Days Craig David