Toccata Classics TOCC0196 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

![Pdf May 2010, "Dvoinaia Pererabotka Otkhodov V Sovetskoi [3] ‘New Beginnings](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7586/pdf-may-2010-dvoinaia-pererabotka-otkhodov-v-sovetskoi-3-new-beginnings-787586.webp)

Pdf May 2010, "Dvoinaia Pererabotka Otkhodov V Sovetskoi [3] ‘New Beginnings

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 368 3rd International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2019) Multifaceted Creativity: Legacy of Alexander Ivashkin Based on Archival Materials and Publications Elena Artamonova Doctor of Philosophy University of Central Lancashire Preston, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—Professor Alexander Vasilievich Ivashkin (1948- numerous successful international academic and research 2014) was one of the internationally eminent musicians and projects, symposia and competitions, concerts and festivals. researchers at the turn of the most recent century. His From 1999 until his death in 2014, as the Head of the Centre dedication, willpower and wisdom in pioneering the music of for Russian Music at Goldsmiths, he generated and promoted his contemporaries as a performer and academic were the interdisciplinary events based on research and archival driving force behind his numerous successful international collections. The Centre was bursting with concert and accomplishments. This paper focuses on Ivashkin’s profound research life, vivacity and activities of high calibre attracting knowledge of twentieth-century music and contemporary international attention and interest among students and analysis in a crossover of cultural-philosophical contexts, scholars, professionals and music lovers, thus bringing together with his rare ability to combine everything in cultural dialogue across generations and boarders to the retrospect and make his own conclusions. His understanding of inner meaning and symbolism bring new conceptions to wider world. His prolific collaborations, including with the Russian music, when the irrational becomes a new stimulus for London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Southbank Centre, the rational ideas. The discussion of these subjects relies heavily on BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Barbican Centre and unpublished archival and little-explored publications of Wigmore Hall, St. -

MUSICAL CENSORSHIP and REPRESSION in the UNION of SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ

SAYI 17 BAHAR 2018 MUSICAL CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSION IN THE UNION OF SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ Abstract In the beginning of 1930s, institutions like Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians were closed down with the aim of gathering every study of music under one center, and under the control of the Communist Party. As a result, all the studies were realized within the two organizations of the Composers’ Union in Moscow and Leningrad in 1932, which later merged to form the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948. In 1948, composer Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was appointed as the frst president of the Union of Soviet Composers by Andrei Zhdanov and continued this post until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Being one of the most controversial fgures in the history of Soviet music, Khrennikov became the third authority after Stalin and Zhdanov in deciding whether a composer or an artwork should be censored or supported by the state. Khrennikov’s main job was to ensure the application of socialist realism, the only accepted doctrine by the state, on the feld of music, and to eliminate all composers and works that fell out of this context. According to the doctrine of socialist realism, music should formalize the Soviet nationalist values and serve the ideals of the Communist Party. Soviet composers should write works with folk music elements which would easily be appreciated by the public, prefer classical orchestration, and avoid atonality, complex rhythmic and harmonic structures. In this period, composers, performers or works that lacked socialist realist values were regarded as formalist. -

Worldnewmusic Magazine

WORLDNEWMUSIC MAGAZINE ISCM During a Year of Pandemic Contents Editor’s Note………………………………………………………………………………5 An ISCM Timeline for 2020 (with a note from ISCM President Glenda Keam)……………………………..……….…6 Anna Veismane: Music life in Latvia 2020 March – December………………………………………….…10 Álvaro Gallegos: Pandemic-Pandemonium – New music in Chile during a perfect storm……………….....14 Anni Heino: Tucked away, locked away – Australia under Covid-19……………..……………….….18 Frank J. Oteri: Music During Quarantine in the United States….………………….………………….…22 Javier Hagen: The corona crisis from the perspective of a freelance musician in Switzerland………....29 In Memoriam (2019-2020)……………………………………….……………………....34 Paco Yáñez: Rethinking Composing in the Time of Coronavirus……………………………………..42 Hong Kong Contemporary Music Festival 2020: Asian Delights………………………..45 Glenda Keam: John Davis Leaves the Australian Music Centre after 32 years………………………….52 Irina Hasnaş: Introducing the ISCM Virtual Collaborative Series …………..………………………….54 World New Music Magazine, edition 2020 Vol. No. 30 “ISCM During a Year of Pandemic” Publisher: International Society for Contemporary Music Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik / Société internationale pour la musique contemporaine / 国际现代音乐协会 / Sociedad Internacional de Música Contemporánea / الجمعية الدولية للموسيقى المعاصرة / Международное общество современной музыки Mailing address: Stiftgasse 29 1070 Wien Austria Email: [email protected] www.iscm.org ISCM Executive Committee: Glenda Keam, President Frank J Oteri, Vice-President Ol’ga Smetanová, -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

Central Opera Service Bulletin Volume 29, Number A

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN VOLUME 29, NUMBER A CONTENTS NEW OPERAS AND PREMIERES 1 NEWS FMNQKRA COMPANIES 18 GOVERNMENT AND NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 24 27 ODNFERENOS H MEM AND REMWftTED THEATERS 29 FORECAST 31 ANNIVERSARIES 37 ARCHIVES AND EXHIBITIONS 39 ATTENTION C0MP0SH8. LIBRE11ISTS, FIAYWRHMTS 40 NUSIC PUBLISHERS 41 EDITIONS AND ADAPTATIONS 4t EOUCATION 44 AFPOINTMEMIS AND RESIGNATIONS 44 COS OPERA SURVEY USA 1988-89 OS INSIDE INFORMATION 57 COS SALUTES. O WINNERS (4 BOOK CORNER 66 OPERA HAS LOST. 73 PERFORMANCE LIST INC. 1969 90 SEASON (CONT.) 83 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN Volume 29, Number 4 Fall/Winter 1989-90 CONTENTS New Operas and Premieres 1 News from Opera Companies 18 Government and National Organizations 24 Copyright 27 Conferences 28 New and Renovated Theaters 29 Forecast 31 Anniversaries 37 Archives and Exhibitions 39 Attention Composers, Librettists, Playwrights 40 Music Publishers 41 Editions and Adaptations 42 Education 44 Appointments and Resignations 46 COS Opera Survey USA 1988-89 56 COS Inside Information 57 COS Salutes. 63 Winners 64 Book Corner 66 Opera Has Lost. 73 Performance Listing, 1989-90 Season (cont.) 83 CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE Founder MRS. AUGUST BELMONT (1879-1979) Honorary National Chairman ROBERT L.B. TOBIN National Chairman MRS. MARGO H. BINDHARDT Please note page 56: COS Opera Survey USA 1988-89 Next issue: New Directions for the '90s The transcript of the COS National Conference In preparation: Directory of Contemporary Opera and Music Theater, 1980-89 (Including American Premieres) Central Opera Service Bulletin • Volume 29, Number 4 • Fall/Winter 1989-90 Editor: MARIA F. -

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

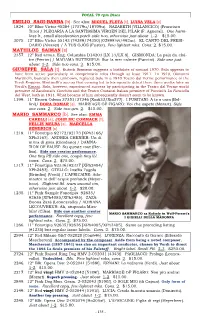

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2. -

GLOBALIZING HOMOPHOBIA: How the American Right Supports and Defends Russia’S Anti-Gay Crackdown Introduction Single People in Countries That Allow Marriage Equality

IN FOCUS GLOBALIZING HOMOPHOBIA: How the American Right Supports and Defends Russia’s Anti-Gay Crackdown Introduction single people in countries that allow marriage equality. Shortly afterward, a member of the In the summer of 2013, as part of a larger Duma proposed a law that would revoke gay effort to channel political dissatisfaction people’s custody of their biological children. by scapegoating minorities, the Russian The bill’s sponsor said in an interview that government escalated its crackdown on children would be better off in orphanages the rights of gay, lesbian, transgender and than with a gay mother or father. bisexual citizens. President Vladimir Putin and his allies found support and guidance in Throughout this process, Russian gay rights their anti-gay efforts from a group eager for groups reported a surge in anti-gay hate an opportunity to notch some victories in the crimes. battle against LGBT freedom and equality: the American right. Russia’s crackdown on LGBT people comes amidst a broad crackdown on the rights On June 11, the Russian Duma passed a law of minorities and political dissenters or, in banning “propaganda” about homosexuality the words of one lawmaker, a campaign to minors, essentially a gag rule criminalizing “to defend the rights of the majority.” On any advocacy for LGBT equality. (Moscow the same day the Duma passed its ban on had already instituted a 100-year ban on gay gay “propaganda,” it also approved a harsh pride parades.) Weeks later, on July 3, Putin anti-blasphemy law promising jail time for signed -

ARSC Journal Encourages Recording Companies and Distributors to Send New Releases of Historic Recordings to the Sound Recording Review Editor

COMPILED BY CHRISTINA MOORE Recordings Received This column lists historic recordings which have been defined as 20 years or older. Historic recordings with one or two recent selections may be included as well. The ARSC Journal encourages recording companies and distributors to send new releases of historic recordings to the Sound Recording Review Editor. Anakkta: Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 1. Selections by Jeanne Gordon, Edward Johnson, Joseph Saucier, Florence Easton, Sarah Fischer, Rodolphe Plamondon, Emma Albani, Eva Gauthier, Paul Dufault, Louise Edvina, Pauline Donalda, Raoul Jobin. Analekta AN 2 7801. CD, recorded 1903-1958. Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 2. Edward Johnson, tenor: selections from Andrea Chenier, La Boheme, La Fanciulla del West, Pagliacci, Louise, Parsifal, Elijah, Fedora, songs, etc. Analekta AN 2 7802. CD, recorded 1914-1928. Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 3. Raoul Jobin, tenor, en concert/live: selections from Herodiade, Madama Butterfly, La Fille du Regiment, Carmen, Louise, Lakme, Les Pecheurs de Perles, etc. Analekta AN 2 8903. CD, recorded 1939-1946. Arhoolie Productions, Inc.: Don Santiago Jimenez. His First and Last Recordings. La Dueiia de la Llave; La Tuna; Eres un Encanto; Antonio de Mis Amores; El Satelite; Ay Te Dejo en San Antonio; El Primer Beso; Las Godornises; Vive Feliz; etc. Arhoolie CD-414 (1994). CD, recorded 1937-38and1979. Folksongs of the Louisiana Acadians. Selections by Chuck Guillory, Wallace "Cheese" Read, Mrs. Odeus Guillory, Mrs. Rodney Fruge, Isom J. Fontenot, Savy Augustine, Bee Deshotels, Shelby Vidrine, Austin Pitre, Milton Molitor. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1989

I nfflfn ^(fe£k i^£to^ Wfr EDITION PETERS »8@ ^^ '^^ ^p52^ RECENT ADDITIONS TO OUR CONTEMPORARY MUSIC CATALOGUE P66905 George Crumb Gnomic Variations $20.00 Piano Solo P66965 Pastoral Drone 12.50 Organ Solo P67212 Daniel Pinkham Reeds 10.00 Oboe Solo P67097 Roger Reynolds Islands From Archipelago: I. Summer Island (Score) 16.00 Oboe and Computer-generated tape* P67191 Islands from Archipelago: II. Autumn Island 15.00 Marimba Solo P67250 Mathew Rosenblum Le Jon Ra (Score) 8.50 Two Violoncelli P67236 Bruce J. Taub Extremities II (Quintet V) (Score) 12.50 Fl, CI, Vn, Vc, Pf P66785 Charles Wuorinen Fast Fantasy (Score)+ 20.00 Violoncello and Piano P67232 Bagatelle 10.00 Piano Solo + 2 Scores neededforperformance * Performance materials availablefrom our rental department C.F. PETERS CORPORATION I 373 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 • (212) 686-4147 J 1989 FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Oliver Knussen, Festival Coordinator 4. J* Sr* » sponsored by the TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER Leon Fleisher, Artistic Director Gilbert Kalish, Chairman of the Faculty I Lukas Foss, Composer-in-Residence Oliver Knussen, Coordinator of Contemporary Music Activities Bradley Lubman, Assistant to Oliver Knussen Richard Ortner, Administrator James E. Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Harry Shapiro, Orchestra Manager Works presented at this year's Festival were prepared under the guidance of the following Tanglewood Music Center Faculty: Frank Epstein Joel Krosnick Lukas Foss Donald MacCourt Margo Garrett Gustav Meier Dennis Helmrich Peter Serkin Gilbert Kalish Yehudi Wyner Oliver Knussen 1989 Visiting Composer/Teachers Bernard Rands Dmitri Smirnov Elena Firsova Peter Schat Tod Machover Kaija Saariaho Ralph Shapey The Tanglewood Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music and sponsored by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. -

The Cambridge Companion To: the ORCHESTRA

The Cambridge Companion to the Orchestra This guide to the orchestra and orchestral life is unique in the breadth of its coverage. It combines orchestral history and orchestral repertory with a practical bias offering critical thought about the past, present and future of the orchestra as a sociological and as an artistic phenomenon. This approach reflects many of the current global discussions about the orchestra’s continued role in a changing society. Other topics discussed include the art of orchestration, score-reading, conductors and conducting, international orchestras, and recording, as well as consideration of what it means to be an orchestral musician, an educator, or an informed listener. Written by experts in the field, the book will be of academic and practical interest to a wide-ranging readership of music historians and professional or amateur musicians as well as an invaluable resource for all those contemplating a career in the performing arts. Colin Lawson is a Pro Vice-Chancellor of Thames Valley University, having previously been Professor of Music at Goldsmiths College, University of London. He has an international profile as a solo clarinettist and plays with The Hanover Band, The English Concert and The King’s Consort. His publications for Cambridge University Press include The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet (1995), Mozart: Clarinet Concerto (1996), Brahms: Clarinet Quintet (1998), The Historical Performance of Music (with Robin Stowell) (1999) and The Early Clarinet (2000). Cambridge Companions to Music Composers