Tlaloc Hildebrandi (Miller, 1950) and Recognition of Its Evolutionarily Significant Units

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argulus Ambystoma, a New Species Parasitic on the Salamander Ambystoma Dumerilii from Mexico (Crustacea: Branchiura: Argulidae)1

Argulus ambystoma, a New Species Parasitic on the Salamander Ambystoma dumerilii from Mexico (Crustacea: Branchiura: Argulidae)1 WILLIAM J. POLY2, Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901-6501 ABSTRACT. A new species of Argulus is described based on 18 specimens taken from the salamander ("achoque" or "ajolote") Ambystoma dumerilii Duges, collected in Lake Patzcuaro, Michoacan, Mexico. Diagnostic characters include the shape of the respiratory areas, number of sclerites in suction cup rods, and structures on the legs of males. Females are heavily stippled, whereas males have a very distinctive pigment pattern consisting of abundant melanophores covering the testes dors ally and two dark, inverted triangular patches on the carapace dorsally. The new species is similar to the North American species, A versicolor,A. americanus, A. maculosus, and A diversus. A single, dorsal pore was observed on each caudal ramus using scanning electron microscopy; these pores have not been reported previously in the Branchiura. OHIO J SCI 103 (3>52-6l, 2003 INTRODUCTION 1991; Osorio-Sarabia and others 1986; Perez-Ponce de Ten species of Argulus Miiller have been collected in Leon and others 1994; Peresbarbosa-Rojas and others Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies. The wide- 1994; Espinosa-Huerta and others 1996; Peresbarbosa- spread exotic, Argulus japonicus Thiele, was found on Rojas and others 1997). A number of endemic taxa exist aquarium fishes, Carassius auratus (Linne) and Astro- in Lake Patzcuaro including several fishes (Cbirostoma notus ocellatus (Agassiz), in Puerto Rico (Bunkley-Williams patzcuaro Meek, C. e. estor Jordan, C. a. attenuatum and Williams 1994), and Vargas and Fallas (1976) found Meek), a crayfish (Cambarellus patzcuarensis Villa- A. -

Morphological and Genetic Comparative

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 373- 383, 2008 Morphological and genetic comparative analyses of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) from Central Mexico, with description of a new species Análisis comparativo morfológico y genético de diferentes poblaciones de Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) del Centro de México, con la descripción de una especie nueva Domínguez-Domínguez Omar1*, Pérez-Rodríguez Rodolfo1 and Doadrio Ignacio2 1Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Fuente de las Rosas 65, Fraccionamiento Fuentes de Morelia, 58088 Morelia, Michoacán, México 2Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, España. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. A genetic and morphometric study of populations of Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis (Bean, 1898) from the Lerma and Ameca basins and Cuitzeo, Zacapu and Chapala Lakes in Central Mexico was conducted. For the genetic analysis, 7 populations were sampled and 2 monophyletic groups were identifi ed with a genetic difference of DHKY= 3.4% (3-3.8%), one being the populations from the lower Lerma basin, Ameca and Chapala Lake, and the other populations from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes. For the morphometric analysis, 4 populations were sampled and 2 morphotypes identifi ed, 1 from La Luz Spring in the lower Lerma basin and the other from Zacapu and Cuitzeo Lakes drainages. Using these 2 sources of evidence, the population from La Luz is regarded as a new species Zoogoneticus purhepechus sp. nov. _The new species differs from its sister species Zoogoneticus quitzeoensis_ in having a shorter preorbital distance (Prol/SL x = 0.056, SD = 0.01), longer dorsal fi n base length (DFL/SL x = 0.18, SD = 0.03) and 13-14 rays in the dorsal fi n. -

The Evolution of the Placenta Drives a Shift in Sexual Selection in Livebearing Fish

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13451 The evolution of the placenta drives a shift in sexual selection in livebearing fish B. J. A. Pollux1,2, R. W. Meredith1,3, M. S. Springer1, T. Garland1 & D. N. Reznick1 The evolution of the placenta from a non-placental ancestor causes a species produce large, ‘costly’ (that is, fully provisioned) eggs5,6, gaining shift of maternal investment from pre- to post-fertilization, creating most reproductive benefits by carefully selecting suitable mates based a venue for parent–offspring conflicts during pregnancy1–4. Theory on phenotype or behaviour2. These females, however, run the risk of mat- predicts that the rise of these conflicts should drive a shift from a ing with genetically inferior (for example, closely related or dishonestly reliance on pre-copulatory female mate choice to polyandry in conjunc- signalling) males, because genetically incompatible males are generally tion with post-zygotic mechanisms of sexual selection2. This hypoth- not discernable at the phenotypic level10. Placental females may reduce esis has not yet been empirically tested. Here we apply comparative these risks by producing tiny, inexpensive eggs and creating large mixed- methods to test a key prediction of this hypothesis, which is that the paternity litters by mating with multiple males. They may then rely on evolution of placentation is associated with reduced pre-copulatory the expression of the paternal genomes to induce differential patterns of female mate choice. We exploit a unique quality of the livebearing fish post-zygotic maternal investment among the embryos and, in extreme family Poeciliidae: placentas have repeatedly evolved or been lost, cases, divert resources from genetically defective (incompatible) to viable creating diversity among closely related lineages in the presence or embryos1–4,6,11. -

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Invasive Species in Aquatic Systems: Population, Community, Food Web And

INVASIVE SPECIES IN AQUATIC SYSTEMS: POPULATION, COMMUNITY, FOOD WEB AND LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVES. by NORMAN MERCADO – SILVA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Zoology) At the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON 2005 i Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………ii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….v Chapter 1……………………………………………………………………………………….1 THESIS INTRODUCTION Chapter II……………………………………………………………………………………....10 WALLEYE RECRUITMENT DECLINE AS A CONSEQUENCE OF RAINBOW SMELT INVASIONS IN WISCONSIN LAKES Chapter III………………………………………………………………………………………47 LONG-TERM CHANGES IN THE FISH ASSEMBLAGE OF THE LAJA RIVER, GUANAJUATO, CENTRAL MEXICO. Chapter IV………………………………………………………………………………………77 FOOD WEB STRUCTURE OF AN IMPACTED SEMI-DESERTIC FRESHWATER SYSTEM IN MEXICO’S CENTRAL PLATEAU Chapter V………………………………………………………………………………………119 FORECASTING THE SPREAD OF INVASIVE RAINBOW SMELT (OSMERUS MORDAX) IN THE LAURENTIAN GREAT LAKES REGION OF NORTH AMERICA ii ABSTRACT INVASIVE SPECIES IN AQUATIC SYSTEMS: POPULATION, COMMUNITY, FOOD WEB AND LANDSCAPE PERSPECTIVES. NORMAN MERCADO-SILVA Under the supervision of Professor Jake Vander Zanden At the University of Wisconsin - Madison The introduction and establishment of invasive species is one of the major causes of changes in the composition, structure, function and viability of freshwater ecosystems. Invasive species have impacts at different levels of organization ranging from genetic (e.g., hybridization and introgression) -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

PARÁMETROS REPRODUCTIVOS DE Dormitator Maculatus

Instituto Tecnológico de Boca del Río Subdirección Académica División de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación “2020, Año de Leona Vicario, Benemérita Madre de la Patria” SECRETARÍA DE EDUCACIÓN PÚBLICA TECNOLÓGICO NACIONAL DE MEXICO INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO DE BOCA DEL RÍO DIVISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO E INVESTIGACIÓN “PARÁMETROS REPRODUCTIVOS DE Dormitator maculatus (BLOCH, 1972) Y SU RELACIÓN CON FACTORES AMBIENTALES DE LA LAGUNA DE ALVARADO VER., PARA PROPONER ASPECTOS BÁSICOS DE CULTIVO” TESIS QUE COMO REQUISITO PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE: DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS EN ACUACULTURA PRESENTA CLAUDIA ARACELI DÁVILA CAMACHO DIRECTOR DE TESIS DRA. ITZEL GALAVIZ VILLA COMITÉ TUTORAL DRA. FABIOLA LANGO REYNOSO, DRA. MARÍA DEL REFUGIO CASTAÑEDA CHÁVEZ, DRA. CECILIA QUIROGA BRAHMS, DR. JESÚS MONTOYA MENDOZA Y DRA. CINTHYA A. SOSA VILLALOBOS. FEBRERO 2020. BOCA DEL RÍO, VERACRUZ, MÉXICO. Km. 12 Carr. Veracruz-Córdoba, Boca del Río, Ver. C.P. 94290 Tel. (229) 690 5010 correo: [email protected] www.tecnm.mx | www.bdelrio.tecnm.m RESUMEN RESUMEN RESUMEN Dormitator maculatus (Bloch, 1792), es una especie nativa, endémica de las vertientes del Atlántico Occidental, desde Estados Unidos de América hasta Brasil, en la región del Sistema Lagunar de Alvarado Veracruz, México. D. maculatus conocida como "Naca", es un especie objetivo de la pesquería artesanal, pues es considerada un recurso de alto valor comercial en la región debido al valor gastronómico de la gónada o hueva. En los últimos años las actividades antropogénicas han impactado su hábitat con contaminantes químicos y biológicos que afectan el agua y los sedimentos, además de la sobreexplotación de la especie por su fácil captura en época de reproducción. -

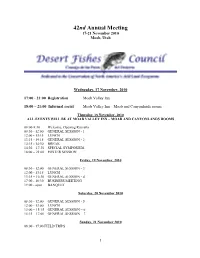

DFC Abstracts2010-11-04

42nd Annual Meeting 17-21 November 2010 Moab, Utah Wednesday, 17 November, 2010 17:00 - 21:00 Registration Moab Valley Inn 18:00 – 21:00 Informal social Moab Valley Inn – Moab and Canyonlands rooms Thursday, 18 November, 2010 ALL EVENTS WILL BE AT MOAB VALLEY INN – MOAB AND CANYONLANDS ROOMS 08:00-8:30 Welcome, Opening Remarks 08:30 - 12:00 GENERAL SESSION - 1 12:00 - 13:15 LUNCH 13:15 - 14:15 GENERAL SESSION - 2 14:15 - 14:30 BREAK 14:30 – 17:30 SPECIAL SYMPOSIUM 18:00 – 21:00 POSTER SESSION Friday, 19 November, 2010 08:30 - 12:00 GENERAL SESSION - 3 12:00 - 13:15 LUNCH 13:15 – 16:30 GENERAL SESSION - 4 17:00 - 18:30 BUSINESS MEETING 19:00 - open BANQUET Saturday, 20 November 2010 08:30 - 12:00 GENERAL SESSION - 5 12:00 - 13:00 LUNCH 13:00 – 15:15 GENERAL SESSION – 6 15:15 – 17:00 GENERAL SESSION – 7 Sunday, 21 November 2010 08:00 - 17:00 FIELD TRIPS 1 42nd Annual Meeting 17-21 November 2010 Moab, Utah Thursday, 18 November, 2010 2010-11-18 08:00:00 OPENING REMARKS GENERAL SESSION 1: Moderator—Dave Speas 2010-11-18 08:30:00 Oregon / Northern California Area Report, November 2010 Scheerer, Paul 1, Leal, Jimmy 2, Mauer, Alan 3, Reid, Stewart 4, Markle, Douglas 5, Sidlauskis, Brian 5, Miller, Stephanie 1, Divine, Paul 6. (1-Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Native Fish Investigations Project, 2- Bureau of Land Management, 3-U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 4-Western Fishes, 5-Oregon State University, 6- California Department of Fish and Game). -

Patterns of Evolution in Gobies (Teleostei: Gobiidae): a Multi-Scale Phylogenetic Investigation

PATTERNS OF EVOLUTION IN GOBIES (TELEOSTEI: GOBIIDAE): A MULTI-SCALE PHYLOGENETIC INVESTIGATION A Dissertation by LUKE MICHAEL TORNABENE BS, Hofstra University, 2007 MS, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 2010 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MARINE BIOLOGY Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Corpus Christi, Texas December 2014 © Luke Michael Tornabene All Rights Reserved December 2014 PATTERNS OF EVOLUTION IN GOBIES (TELEOSTEI: GOBIIDAE): A MULTI-SCALE PHYLOGENETIC INVESTIGATION A Dissertation by LUKE MICHAEL TORNABENE This dissertation meets the standards for scope and quality of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi and is hereby approved. Frank L. Pezold, PhD Chris Bird, PhD Chair Committee Member Kevin W. Conway, PhD James D. Hogan, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Lea-Der Chen, PhD Graduate Faculty Representative December 2014 ABSTRACT The family of fishes commonly known as gobies (Teleostei: Gobiidae) is one of the most diverse lineages of vertebrates in the world. With more than 1700 species of gobies spread among more than 200 genera, gobies are the most species-rich family of marine fishes. Gobies can be found in nearly every aquatic habitat on earth, and are often the most diverse and numerically abundant fishes in tropical and subtropical habitats, especially coral reefs. Their remarkable taxonomic, morphological and ecological diversity make them an ideal model group for studying the processes driving taxonomic and phenotypic diversification in aquatic vertebrates. Unfortunately the phylogenetic relationships of many groups of gobies are poorly resolved, obscuring our understanding of the evolution of their ecological diversity. This dissertation is a multi-scale phylogenetic study that aims to clarify phylogenetic relationships across the Gobiidae and demonstrate the utility of this family for studies of macroevolution and speciation at multiple evolutionary timescales. -

Resistance and Resilience of Murray-Darling Basin Fishes to Drought Disturbance

Resistance and Resilience of Murray- Darling Basin Fishes to Drought Disturbance Dale McNeil1, Susan Gehrig1 and Clayton Sharpe2 SARDI Publication No. F2009/000406-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 602 SARDI Aquatic Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 April 2013 Final Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority - Native Fish Strategy Project MD/1086 “Ecosystem Resilience and the Role of Refugia for Native Fish Communities & Populations” McNeil et. al. 2013 Drought and Native Fish Resilience Resistance and Resilience of Murray- Darling Basin Fishes to Drought Disturbance Final Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority - Native Fish Strategy Project MD/1086 “Ecosystem Resilience and the Role of Refugia for Native Fish Communities & Populations” Dale McNeil1, Susan Gehrig1 and Clayton Sharpe2 SARDI Publication No. F2009/000406-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 602 April 2013 Page | ii McNeil et. al. 2013 Drought and Native Fish Resilience This Publication may be cited as: McNeil, D. G., Gehrig, S. L. and Sharpe, C. P. (2013). Resistance and Resilience of Murray-Darling Basin Fishes to Drought Disturbance. Final Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Authority - Native Fish Strategy Project MD/1086 ―Ecosystem Resilience and the Role of Refugia for Native Fish Communities & Populations‖. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2009/000406-1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 602. 143pp. Front Cover Images – Lake Brewster in the Lower Lachlan River catchment, Murray-Darling Basin during extended period of zero inflows, 2007. Murray cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii), olive perchlet (Ambassis agassizii) and golden perch (Macquaria ambigua) from the, lower Lachlan River near Lake Brewster, 2007 (all images - Dale McNeil). -

Multi-Locus Fossil-Calibrated Phylogeny of Atheriniformes (Teleostei, Ovalentaria)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 86 (2015) 8–23 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Multi-locus fossil-calibrated phylogeny of Atheriniformes (Teleostei, Ovalentaria) Daniela Campanella a, Lily C. Hughes a, Peter J. Unmack b, Devin D. Bloom c, Kyle R. Piller d, ⇑ Guillermo Ortí a, a Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA b Institute for Applied Ecology, University of Canberra, Australia c Department of Biology, Willamette University, Salem, OR, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, LA, USA article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships among families within the order Atheriniformes have been difficult to resolve Received 29 December 2014 on the basis of morphological evidence. Molecular studies so far have been fragmentary and based on a Revised 21 February 2015 small number taxa and loci. In this study, we provide a new phylogenetic hypothesis based on sequence Accepted 2 March 2015 data collected for eight molecular markers for a representative sample of 103 atheriniform species, cover- Available online 10 March 2015 ing 2/3 of the genera in this order. The phylogeny is calibrated with six carefully chosen fossil taxa to pro- vide an explicit timeframe for the diversification of this group. Our results support the subdivision of Keywords: Atheriniformes into two suborders (Atherinopsoidei and Atherinoidei), the nesting of Notocheirinae Silverside fishes within Atherinopsidae, and the monophyly of tribe Menidiini, among others. We propose taxonomic Marine to freshwater transitions Marine dispersal changes for Atherinopsoidei, but a few weakly supported nodes in our phylogeny suggests that further Molecular markers study is necessary to support a revised taxonomy of Atherinoidei.