Towards a Pragmatic Approach to Understanding Modern Advertising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

Revised Syllabus (Choice Based Credit System)

DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR REVISED SYLLABUS (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR POST GRADUATE COURSE IN LINGUISTICS SYLLABUS APPLICABLE FOR STUDENTS SEEKING ADMISSION TO M.A.IN LINGUISTICS FROM THE ACADEMIC YEAR 2015-16 ONWARDS. 1 SPECIFICATIONS/ COMMON FEATURES OF THE COURSES Each course is divided into five equal units. Each course has six credit points and 100 marks with minimum 10 contact hours per week consisting of lectures, tutorials, seminars. The Internal Assessment carries 30 marks and end semester examination carries 70 marks. In the end semester examination, a unit of each course caries 14 marks. The Internal Assessment consists of the following: 1. Written Examination: 15 marks 2. Seminar/ Assignment: 10 marks 3. Attendance in the class: 05 marks 2 COURSE STRUCTURE NO. OF SEMESTER – 04 NO. OF COURSES – 20 FULL MARKS – 2000 DISTRIBUTION OF MARKS: (FOR EACH COURSE) FULL MARKS: 100 INTERNAL TEST: 30 PASS MARK: 12 END SEMESTER: 70 PASS MARK: 28 GRADE POINT 6 FOR EACH COURSE CONTACT HOURS: MINIMUM 10 HOURS FOR EACH UNIT IN EACH COURSE 1ST SEMESTER: 101 INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE 102 INTRODUCTION TO GENERAL LINGUISTICS 103 PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 104 INTRODUCTION TO SEMANTICS 105 MORPHOLOGY 2ND SEMESTER: 201 SOCIOLINGUISTICS 202 LANGUAGE TEACHING 203 INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS (OPEN COURSE) 204 STRUCTURE OF NORTH EAST INDIAN LANGUAGES (OPEN COURSE) 205 INTRODUCTORY TRANSFORMATIONAL SYNTAX 3RD SEMESTER: 301 PSYCHOLINGUISTICS 302 TOPICS IN GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY 303 HISTORICAL AND COMPARATIVE LINGUISTICS 304(A) LANGUAGE HISTORY: TIBETO-BURMAN LANGUAGES (OPTIONAL PAPER) 304(B) LANGUAGE HISTORY: COMPARATIVE INDO-ARYAN (OPTIONAL PAPER) 305 TRANSLATION THEORY 4TH SEMESTER: 401 LEXICOLOGY AND LEXICOGRAPHY 402 BILINGUALISM AND LANGUAGE PLANNING 403 LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY, UNIVERSALS AND CONVERGENCE 404 (A) DOCUMENTATION AND DESCRIPTION OF ENDANGERED LANGUAGES (OPTIONAL PAPER) 404(B) COMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICS (OPTIONAL PAPER) 405 DISSERTATION/PROJECT 3 FIRST SEMESTER Full Marks: 30+70=100 COURSE NO. -

Language Contact Between Uyghur and Chinese in Xinjiang, PRC: Uyghur Elements in Xinjiang Putonghua

Language contact between Uyghur and Chinese in Xinjiang, PRC: Uyghur elements in Xinjiang Putonghua ABLIMIT BAKI Abstract This article reports on language contact between Uyghur and Chinese in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang in China. It proposes that the massive influx of Han Chinese migrants to Xinjiang resulted in intense language con- tact between the speakers of Uyghur and Chinese. As a result of this, these two languages are mutually affecting each other in the region. The focus of this article is on the influence of Uyghur on Putonghua in Xinjiang. Four catego- ries of this influence are reported: (1) phonological influence that produces Putonghua sounds similar to Uyghur sounds, exemplified by the dropping of tones, the changing of sounds and the addition of certain sounds which are closer to those in Uyghur; (2) lexical influence, exemplified by introducing into Putonghua elements of the Uyghur lexicon which are then adapted to resemble Putonghua lexical forms; (3) grammatical influence that produces Putonghua grammatical structures similar to those of Uyghur, exemplified by changing word order in Putonghua grammatical structures; and (4) semantic influence that makes use of Uyghur expressions in Putonghua through literal transla- tion, exemplified by using Uyghur similes and metaphors directly to describe people and things in certain contexts. Keywords: Uyghur, Putonghua; contact situation; language-to-language influence; language transfer; agentivity; borrowing; imposition; variety; interlanguage. 1. Introduction There is an important literature on the mutual influence of languages in contact situations. Many scholars have shown that the direction of the influence is not only from a majority language to a minority language, but also vice versa. -

Linguistics February 4, 2012

Outline of Linguistics February 4, 2012 Contents SOCI>Linguistics .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 SOCI>Linguistics>Kinds .............................................................................................................................................. 5 SOCI>Linguistics>Communication .............................................................................................................................. 5 SOCI>Linguistics>Communication>Physical ......................................................................................................... 6 SOCI>Linguistics>Communication>Verbal ............................................................................................................ 7 SOCI>Linguistics>Structure ......................................................................................................................................... 7 SOCI>Linguistics>Language ........................................................................................................................................ 7 SOCI>Linguistics>Language>Kinds ....................................................................................................................... 9 SOCI>Linguistics>Language>Kinds>Phonetic .................................................................................................. 9 SOCI>Linguistics>Language>Kinds>Affix ....................................................................................................... -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 283 International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2018) An Analysis of the Formation of Regional Linguistic Universals* Yongming Hong Jiangmin Zhao School of Language School of Language Xinjiang Normal University Xinjiang Normal University Urumqi, China 830054 Urumqi, China 830054 Abstract—Linguistic universality is prevalent in all discussion in the academic world, and it is self-evident. To languages, and its sources are mainly natural ability, this end, the discussion continues on the formation of pragmatic function, cognitive psychology, diachronic processes and the process of regional language commonality, development and language contact. The commonality of that is, how regional languages reach heterogeneous language can be divided into three categories: common isomorphism under the influence of language contact language, kinship language and regional linguistic (different sources, but the structure is the same). commonality. Based on the linguistic generality theory, this paper analyzes the five main ways of regional linguistic The so-called regional language commonality, also common features formation through the analysis of regional known as the commonality of language alliances, refers to linguistic structure and social function variation. the language categories shared by all languages in a certain region. Shinda Keji believes that the two adjacent languages Keywords—language contact; regional language; common will gradually become similar even if the language is features different; the languages with different language types and similar type characteristics are “language alliances”; I. INTRODUCTION sometimes they are collectively referred to as “language Language commonality refers to the language category circles” regardless of which language they belong to. -

4.Format.Hum- SYNTAXES of NIAS LANGUAGE in PERSPECTIVE

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 5, Issue 11, Nov 2017, 33-44 © Impact Journals SYNTAXES OF NIAS LANGUAGE IN PERSPECTIVE SIAMIR MARULAFAU Reserch Scholar, Jalan Universitas Nomor, USU Padang Bulan ABSTRACT This writing is about “Syntaxes of Nias Language in Perspective”, that describes the varieties and the forms of syntaxes of Nias language of, how it is formed and its system formulated as basic cases, to be analyzed.In the case of solving the problems, the writer used the theory of P.H. Mathew, related to the topic being discussed in relation to the system. The method used in this scientific writing is descriptive qulitative method,which describes and gives description of syntaxes, used in Nias language.This findings indicate that, the syntaxes of Nias language can be described in the forms of words,patterns and become sentences in Nias language. KEYWORDS : Syntax, Form, Pattern INRODUCTION Every language in the world has different patterns and the use of the language, depends on the use of the language in societies.The patterns of Indoesian language, English and other languages have different forms, as the patterns of Nias language as well.The improvement of Regional language, such as Nias language is not only to keep up the existence of the language itself, but to give the function for the developer and users of Indonesian language regarding, as a national language that may not be separated from one with another because, both of them have a very close relation. -

On Pragmatic Strategies for Avoidance of Explicitness in Language

www.ccsenet.org/ass Asian Social Science Vol. 6, No. 10; October 2010 On Pragmatic Strategies for Avoidance of Explicitness in Language Peijun Chen Foreign Language Teaching Department, Jining Medical College Rizhao 276826, Shandong, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract It is common that people avoid explicit language in daily communication. This paper intends to discuss various pragmatic strategies used for avoidance of explicitness in language and to analyze sorts of reasons for the explicitness from the perspective of pragmatics. Keywords: Explicitness, Conversational implicature, Presequences, Hedges, Politeness Principle, Adaptation theory 1. Introduction The most simple way for people to speak is that, a speaker utters a sentence and means accurately what he intends to say in the original meaning. That is to way, the speaker conveys his communicative intention in by means of direction expression. However, this straightforward means is not unique. In other words, in daily life, in most cases, people do not utter what they intend to say directly and without preamble, but insinuate to others to express their thought indirectly and implicitly. We refer to this phenomenon as indirectness or implicitness of language use, which are relative with directness or explicitness of language. The strategies and means people use to avoid explicit language are various. In this paper, the author is going to conduct a preliminary research in pragmatic strategies for avoidance of explicit language and then analyze the various reasons for avoidance of explicitness in language from the perspective of pragmatics. 2. Pragmatic strategies to avoid explicit language Actually, either direct (or explicit) expression means or indirect (or implicit) expression means, are use of language by people. -

Chapter 27 Some Aspects of Cartographic and Linguistic

Section 10 Toponymic research and online material that was elaborated mainly out of an data files (including gazetteer production) and aspects of academic, mostly linguistic, interest in place names and toponymic data exchange formats and standards.”1 documentation focuses on toponymy as a sub discipline of linguistics. Gazetteers or databases of this kind primarily focus on These two groups of publications basically focus on the correct spelling of names and their categorization Chapter 27 Some aspects of cartographic different aspects of place names though they sometimes and localization, although also other aspects may be and linguistic toponymic sources overlap. taken into consideration (correct standard pronunciation, administrative affiliation etc.). These Hubert Bergmann Apart from such sophisticated toponymic sources a lot of publications are therefor useful for finding the official other linguistic publications may also contain spelling of the name of a topographic object, or – in information that can be useful when dealing with other words – its standardised form. An example for a toponyms. Dictionaries for example may contain 27.1 Introduction print publication of this kind is the “Gazetteer of toponyms as well. With regard to several aspects of Austria”, published by Joseph Breu in 1975. Its entries Why would someone want to consult such sources? In geographical names they may even be the first source of contain the following information: Standard German order to find the official spelling of the name of a information. Even grammars may be of relevance for the pronunciation according to the International Phonetic topographic object (its standardised form), its meaning, study of place names, because toponyms may follow Alphabet (IPA), description of the feature (topographic its derived versions (names of its inhabitants, adverbs specific rules when it comes to the grammatical system category, description of the location in words, derived from it. -

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation South Ural State University INSTITUTE of LINGUISTICS ANDINTERNATIONA

Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation South Ural State University INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTICS ANDINTERNATIONAL COMMUNICATION DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES Reviewer Head of department _______________/S.G. Nestertsova/ __________/K. N. Volchenkova/ ________________________________________________________ ______________________ 2017 _________________________ 2017 THE CONCEPT OF TIME IN ENGLISH AND ARABIC MASTER’STHESIS Supervisor: Associate Professor, T.V. Vasilieva Candidate of Linguistics _________________________ 2017 Student: Mohammed Raheemah Kadhim Group: Ph-281 _________________________2017 Controller: Associate Professor L.N. Ovinova Candidate of Pedagogy ________________________2017 Defended with the grade: __________________________ __________________________2017 Chelyabinsk 2017 Abstract The topic of the master’s thesis is “Concept of Time in English and Arabic”. Time is an integral part of all human experiences, because everything that exists exists in time, which makes time a universal concept. The encoding of time through language, however, is linguistically and culturally specific. We need to know the differences, because they determine our underlying attitudes toward others and toward ourselves, and it is these attitudes that in their turn determine most of the problems confronting human beings in the process of intercultural communication. Globalization is blurring borders between states and people. That is why it is important to know the culturally different ways the world is structured, and time determines -

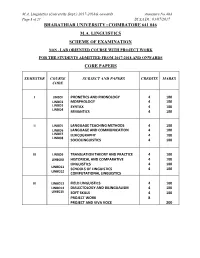

Coimbatore 641 046 Ma Linguistics Scheme Of

M.A. Linguistics (University Dept.) 2017-2018& onwards Annexure No.48A Page 1 of 27 SCAA Dt.: 03/07/2017 BHARATHIAR UNIVERSITY::COIMBATORE 641 046 M.A. LINGUISTICS SCHEME OF EXAMINATION NON - LAB ORIENTED COURSE WITH PROJECT WORK FOR THE STUDENTS ADMITTED FROM 2017-2018 AND ONWARDS CORE PAPERS SEMESTER COURSE SUBJECT AND PAPERS CREDITS MARKS CODE I LINBOI PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY 4 100 LINBO2 MORPHOLOGY 4 100 LINBO3 SYNTAX 4 100 LINBO4 SEMANTICS 4 100 II LINBO5 LANGUAGE TEACHING METHODS 4 100 LINBO6 LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION 4 100 LINBO7 LEXICOGRAPHY 4 100 LINBO8 SOCIOLINGUISTICS 4 100 III LINBO9 TRANSLATION THEORY AND PRACTICE 4 100 4 100 LINBOI0 HISTORICAL AND COMPARATIVE LINGUISTICS 4 100 LINBO11 SCHOOLS OF LINGUISTICS 4 100 LINBO12 COMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICS FIELD LINGUISTICS 4 100 IV LINBO13 LINBO14 DIALECTOLOGY AND BILINGUALISM 4 100 LINB015 SOFT SKILLS 4 100 PROJECT WORK 8 PROJECT AND VIVA VOCE 200 M.A. Linguistics (University Dept.) 2017-2018& onwards Annexure No.48A Page 2 of 27 SCAA Dt.: 03/07/2017 ELECTIVE PAPERS SEMESTER COURSE SUBJECT AND PAPERS CREDITS MARKS CODE INTRODUCTION TO LANGUAGE 4 100 I LINGE01 STRUCTURE AND LANGUAGE USE FORENSIC LINGUISTICS 4 100 II LINGE02 LANGUAGE CULTURE AND SOCIETY 4 100 III LINGE03 IV LINGE04 NEUROLINGUISTICS 4 100 SUPPORTIVE PAPERS SEMESTER COURSE SUBJECT AND PAPERS CREDITS MARKS CODE I LINGS01 BASIC PHONETICS 2 50 LINGS02 BASICS OF TRANSLATION 2 50 II LINGS03 INTRODUCTION TO DRAVIDIAN LANGUAGES 2 50 2 50 LINGS04 LANGUAGE FOR SPECIAL PURPOSE III LINGS05 DICTIONARY MAKING 2 50 Total 90 2250 Includes 25% continuous internal assessment marks. -

Wikipedia Cultural Diversity Dataset: a Complete Cartography for 300

Wikipedia Cultural Diversity Dataset: A Complete Cartography for 300 Language Editions Marc Miquel-Ribé David Laniado Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Catalunya Eurecat, Centre Tecnològic de Catalunya [email protected] [email protected] Abstract content by each community obeys to different dynamics influenced by cultural and contextual factors (Hecht & In this paper we present the Wikipedia Cultural Diversity Gergle, 2010a; Samoilenko, Karimi, Edler, Kunegis, & dataset. For each existing Wikipedia language edition, the Strohmaier, 2016). dataset contains a classification of the articles that represent its associated cultural context, i.e. all concepts and entities related In order to understand better the composition of each to the language and to the territories where it is spoken. We Wikipedia language edition, in our previous work (Miquel- describe the methodology we employed to classify articles, and Ribé, 2016; Miquel-Ribé & Laniado, 2016) we developed the rich set of features that we defined to feed the classifier, and that are released as part of the dataset. We present several a methodology to identify the articles related to the editors’ purposes for which we envision the use of this dataset, geographical and cultural context (i.e. their places, including detecting, measuring and countering content gaps in traditions, language, agriculture, biographies, etc.). We the Wikipedia project, and encouraging cross-cultural research named such articles Cultural Context Content (CCC). in the field of digital humanities. Results showed that among the largest 40 Wikipedia language editions, these articles represent on average the 25% of all the content and are mostly exclusive, i.e. they Introduction have no equivalence across language editions. -

Academic Disciplines

Outline of academic disciplines Main article: Discipline (academia) • Musical composition • Music education An academic discipline or field of study is a branch of • Music history knowledge that is taught and researched as part of higher • Musicology education. A scholar’s discipline is commonly defined • and received by the university faculties and learned soci- Historical musicology • eties to which he or she belongs and the academic jour- Systematic musicology nals in which he or she publishes research. However, no • Ethnomusicology formal criteria exists for defining an academic discipline. • Music theory Disciplines vary between well-established ones that exist • Orchestral studies in almost all universities and have well-defined rosters of • Organology journals and conferences and nascent ones supported by • Organ and historical keyboards only a few universities and publications. A discipline may • have branches, and these are often called sub-disciplines. Piano • Strings, harp, oud, and guitar (outline) There is no consensus on how some academic disci- • Singing plines should be classified (e.g., whether anthropology • and linguistics are discipline of social sciences or fields Woodwinds, brass, and percussion within the humanities). More generally, the proper cri- • Recording teria for organizing knowledge into disciplines are also • Dance (outline) open to debate. • The following outline is provided as an overview of and Choreography topical guide to academic disciplines. • Dance notation • Ethnochoreology • History of dance 1 Arts