Review of Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ijllt) Issn: 2617-0299

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT) ISSN: 2617-0299 www.ijllt.org Formalist Criticism: Critique on Reynaldo A. Duque’s Selected Ilokano Poems Ranec A. Azarias1* & Apollo S. Francisco 2 1Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College-Santiago Campus, Santiago, Ilocos Sur, Philippines 2 Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College-Sta. Maria Campus, Sta. Maria, Ilocos Sur, Philippines Corresponding Author: Ranec A. Azarias, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: September 18, 2019 Philippines is country with rich literatures that embody the culture and history Accepted: October 16, 2019 of the Filipinos. One of the rich sources of literatures is that of the Ilokano Published: November 30, 2019 people in the Ilocos region of Luzon. However, dearth of critical studies on Volume: 2 Ilokano literature is evident. As such, this study analyzed the selected Issue: 6 DOI: 10.32996/ijllt.2019.2.6.44 contemporary Ilokano poems of Reynaldo A. Duque using the frameworks of KEYWORDS Formalism namely literariness and organic whole. Through content analysis and close reading, the study discovered that Reynaldo A. Duque employed archetypal technique, eight literary devices in his poems: persona, tone, mood, rhyme, rhythm, formalism, Ilokano literature, figures of speech, symbolism, imagery, theme and syntax; the meaning of the literary criticism poem progresses as the eight devices are being decoded; each device gives a clue to the meaning of the poems. Nevertheless, Ilokano literature and text still reveal universal truth specifically on universality of human character or emotions and of the society’s culture; it possesses literary elements. 1. INTRODUCTION1 standpoint, a work of literature is evaluated on the In understanding a work of literature, one must be basis of its literary devices and the susceptibility of the familiar with literary criticism. -

Mutual Conversion of Spanish Missionaries and Filipino Natives

Mutual Conversion of Spanish Missionaries and Filipino Natives Mutual Conversion of Spanish Missionaries and Filipino Natives: Christian Evangelization in the Philippines, 1578 – 1609 A. Introduction The period of 1578 to 1609 can be called the “golden age” of Christian evangelization in the Philippines by the Spanish missionaries. John Leddy Phelan’s notes: “The decades from 1578 until 1609, after which date the Philippines began to feel the full impact of the Dutch war, were the "golden age" of the missionary enterprise. Fired with apostolic zeal, this generation of missionaries was inspired by a seemingly boundless enthusiasm.”1 This “golden age” was marked by an amazingly rapid and peaceful evangelization of the Filipino natives by the Spanish missionaries. By early 1600’s, less than 50 years after a sustained presence in the islands, most of the natives were converted to Christianity with approximately 250 missionaries. "As the sixteenth century drew to its close, the Spanish missionaries in the Philippines had laid the firm foundation upon which was to rise the only Christian-Oriental nation in the Far East."2 The military conquest of Philippine islands was relatively bloodless in comparison to the conquests of West Indies. Catholicism provided the main instrument of colonization for the Spanish conquistadores. In effect there was not much use of Spanish military might as there was for Spanish missionaries. Indeed the colonization of the Philippines by Spain was done through Chrisitianity. Behind this relatively peaceful assimilation of the Philippines through Christianity are abundant dynamics of mutual conversion between Spanish missionaries and Filipino natives. In the encounter between Christianity and indigenous religion of the Filipino natives both 1 John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565 – 1700, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959, 70. -

The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803;

fA/<(Yf r* ^,<?^ffyf/M^^ f^rM M<H ^ ^y^ /"^v/// f> .6S THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS 1493-1898 The PHILIPPINE ISLANDS 1493-1898 Explorations by Early Navigators, Descriptions of the Islands and their Peoples, their History and Records of the Catholic Missions, as related in contemporaneous Books and Manuscripts, showing the Political, Eco- nomic, Commercial and Religious Conditions of those Islands from their earliest relations with European Nations to the close of the Nineteenth Century TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINALS Edited and annotated by Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, with historical intro- duction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. With maps, portraits and other illustrations Volume XXXV—1640-164^ The Arthur H. Clark Company Cleveland, Ohio MCMVI COPYRIGHT 1906 THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXV Preface. ........ 9 Documents of 1640- 1644 The Dominican missions, 1635-39. Baltasar de Santa Cruz, O. P. [From his Historia de la provincia del Santo Rosario (Zaragoza, 1693).] 25 The Recollect missions, 1625-40. [Extracts from the works of Juan de la Concepcion and Luis de Jesus.] . '59 News from Filipinas, 1640-42. [Unsigned]; [Manila, 1641], and July 25, 1642 . .114 Decree regarding the Indians. Felipe IV; ^arago9a, October 24, 1642 . .125 Formosa lost to Spain. Juan de los Angeles, O.P.; Macasar, March, 1643 • • .128 Letter to Corcuera. Felipe IV; Zaragoza, August 4, 1 643 1 63 Documents of 1644- 1649 Concessions to the Jesuits. Balthasar de La- gunilla, S. J., and others; 1640-44 . .169 Events in the Philippines, 1643-44. [Un- signed and undated.] . -

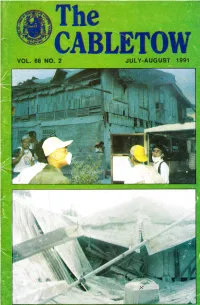

Volume 68, Issue 2 (1991)

CONTENTS Editorial Grand Masters Zeroing- ln Corner 3 All about Volcanos 5 Volcanoes the World Over 6 Mount Pinatubo 8 Pinatubo Pictorial 10 The Lesser Lights 23 Progress Report 29 Voice from the Past 34 The Philatelist 36 Masonic Education 39 My Dear Son 41 Brotherhood Amist Adversity 42 News in Pictures 44 EDITORIAL STAFF , ,..........,.......,...,..,. F ERNANDO VT,,PASGUA;,.YP. """" Ed-itoi:ini"'i#,..'......................,,....,'' G.'..,DU;MrXO','...'.'.. , ....,.., I,.ANTONiO OSCAR L. FUNG ,.,, ",,"",,,'.c.,iinitiiibiiini:,Ediibi;i,,,,,,,t:,,,,,,,:,,';,;,., ,,, MABA'II GI HERNANDEZ CONRADO V: SANG-A ::'FELIFRANCO',R, LUTO OUR COVER : The state of pinatubo Lodge No. 52, F & A M. After the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo CABLETOW I EDITORIAL PREPARING FOR DISASTERS Within a period of less than onp year, three major natural ca' lamities or disasters occurred in the Philippines. The first disaster that struck was the Intensity 7 earthquake of July 15, 1990 that devastated Baguio City' Dagrrpan City' Cabanatuan City and wide areas in the provinces of Nueva ncila, Nueva Vizcaya, Pangasinan, La Union and Benguet. On November 12 to14,1990 the second disaster occurred in the form of Typhoon "RUPING" that cut a wide swath of destruc' tion through Central Visayas rvith winds of 165 kilometers per hour, particula4ly thru Cebu Cit-v, Bacolod City,Ikril<l City and the provinces in Cebu, Negros and Panay Islands. As if these were not enough, a third disaster took place u'hen the Mt. Pinatubo volcano that had been dormant for 6001'ears erupted with a tremendous explosion 9n June 15, l99l that blerv off its top aild sent ashes and pumiceinto theatmosphere, turning day into night in several towns in the provinces of Zambales, Tarlac, Pampanga and Bataan, and causing lahar (mud-flou's) to go cascading down the mountain to the low-lying towns of these provinces. -

CATALOGUE of RARE BOOKS University of Santo Tomas Library

CATALOGUE OF RARE BOOKS University of Santo Tomas Library VOLUME 3, PART 1 FILIPINIANA (1610-1945) i CATALOGUE OF RARE BOOKS i ii CATALOGUE OF RARE BOOKS UNIVERSITY OF SANTO TOMAS LIBRARY VOLUME 3 : Filipiniana 1610-1945 Editor : Angel Aparicio, O.P. Manila, Philippines 2005 iii Copyright © 2005 by University of Sto. Tomas Library and National Commission for Culture and the Arts All rights reserved ISBN 971-506-323-3 Printed by Bookman Printing House, Inc. 373 Quezon Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines iv CONTENTS List of Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols Used vi List of Figures viii Foreword xi Prologue xiii Catalogue of Filipiniana Rare Books Printed from the Year 1610 to 1945 1 Catalogue of Filipiniana Rare Books (Without Date) 707 Appendix A: Reprints 715 Appendix B: Photocopies 722 Appendix C: Bibliography on the University of Santo Tomas Internment Camp 727 Appendix D: The UST Printing Press 734 References 738 Indexes Authors 742 Titles 763 Cities and Printers 798 v LIST of ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS and SYMBOLS USED Book sizes F° - Folio (more than 30 cm.) 4° - Quarto (24.5-30 cm.) 8° - Octavo (19.5-24 cm.) 12° - Duodecimo (17.5-19 cm.) 16° - Sectodecimo (15-17 cm.) 18° - Octodecimo (12.5-14.5 cm.) 32° - Trigesimo-secundo (10-12 cm.) a.k.a. - also known as app. - appendix bk., bks. - book(s) ca. - circa (about) col./ cols. - column(s) comp. - compiler D.D. - Doctor of Divinity ed. - edition/editor/editors Est., Estab. - Establicimiento (establishment) et al. - et alii (and others) etc. - et cetera (and the other; the rest) front. -

Las Costumbres De Los Tagalos De Filipinas Según El Pa- Dre Plasencia

PRESENCIA EXTREMEÑA EN EXTREMO ORIENTE: LAS COSTUMBRES DE LOS TAGALOS DE FILIPINAS SEGÚN EL PA- DRE PLASENCIA FERNANDO CID LUCAS AEO. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid A mi tocayo, al profesor Serrano Mangas, in memoriam INTRODUCCIÓN La única vez que puede hablar en persona con esa “biblioteca humana” que fue el dominico Jesús González Valles creo que fue en Madrid, al hilo de un congreso que organizaba la Universidad Complutense -o, mejor y más justo sería decir, en colabora- ción con la Asociación de Estudios Japoneses en España- hace ya bastantes años. Con el respeto que me causaba saber que él era el autor de textos impecables que yo había leído y releído, dedicados a la religión y la espiritualidad japonesa, cuyos títu- los no me resisto a no incluir aquí, siquiera en breve nota a pie de página1, sólo acerté a darle la enhorabuena por su ponencia, entre tembloroso y titubeante. Supongo que 1 Entre otros títulos, más que reseñables son sus libros Historia de la filosofía japonesa, Madrid, Tecnos, 2002 y Filosofía de las artes japonesas. Artes de guerra y caminos de paz, Madrid, Verbum, 2009; o sus artículos seminales titulados: “Primeras influencias de la filosofía occidental en el pensamiento japonés”, Studium, nº 4, 1964, pp. 75-112; “El encuentro del Cristianismo con el Shintoismo”, Studium, nº 9, 1969, 3-33; “Las fuentes de la espiritualidad religiosa japonesa”, Teología espiritual, nº 54, vol. XVIII, 1974, pp.339-362 y otros muchos más. Alcántara, 81 (2015): pp. 97-107 98 FERNANDO CID LUCAS para darme confianza o para quitarme el respeto que él me infundía, mientras nos es- trechábamos la mano, me preguntó: “¿De dónde es usted?”, a lo que yo respondí con un seco: “De Cáceres”, arguyendo el dominico de forma inmediata: “Pues mucho hi- cieron los extremeños en Extremo Oriente, no se crea que sólo estuvieron presente en América”. -

Sociological Time Travel: Criminality and Criminologists in the Philippine Past

Filomin Candaliza-GutieRRez Sociological Time Travel: Criminality and Criminologists in the Philippine Past This essay is a reflexive assessment of the authors’ research experiences crossing from sociology to history and back for her Ph.D. dissertation on criminality using old archival documents. It highlights the differences in the methodological approaches and data collection practices between the two disciplines, from notions of sampling to the regard of what constitutes authoritative sources data. More importantly, it recognizes the common quest of historical sociology and social history to draw intellectual inspiration and fresh research impetus from the orientations and techniques from one another’s discipline. Finally, the piece narrates her post-dissertation work on the history of knowledge production on criminality in the Philippines, a project that necessitated the historical grounding of biographies, social scientific knowledge, and of research itself. Keywords: Historical sociology, social history, primary sources, secondary data, Philippine criminology Philippine Sociological Review (2013) • Vol. 61 • pp. 69-86 69 Arrest Warrant Ordering the Capture of a Criminal Fugitive. (Source: Philippine National Archives. Asuntos Criminales, Varias Provincias, 1850-1901) 70 Philippine Sociological Review (2013) • Vol. 61 • no. 1 ociology is notorious for doing cross-sectional analyses of contemporary society. For many Filipino researchers in sociology, S the ‘biography-history’ or the ‘troubles-issues’ guidepost of C.W. Mills (1959) translates well to locating individuals in their contemporary milieu rather than in sustained temporal continuities that engage social life in the Philippine past. Doing the latter is typically entrusted to historians. Much of the sociological researchers in the Philippines have the tendency to relegate the history of the topic being studied as a section allotted to the background, providing some cursory context of what had happened in the past about such a problem. -

Notice Concerning Copyright Restrictions

NOTICE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS This document may contain copyrighted materials. These materials have been made available for use in research, teaching, and private study, but may not be used for any commercial purpose. Users may not otherwise copy, reproduce, retransmit, distribute, publish, commercially exploit or otherwise transfer any material. The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be "used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research." If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. 26. Geothermal Legacy from the Filipinos and Later Migrants by Leonard0 M. Ote Arturo P. Alcaru Agnes C. de Jesus Abstract The early Filipinos did not make much use of the terrestrial heat so abundantly manifested in the region. However, they may have used a mixture of oil and bits of sulfur-rich rocks for medicinal and mystical PROLOGUE purposes. References to fire or heat were associated with volcanoes, which early Filipinos revered as homes for TmPmLIPPmE ARcmELAGo CONSISTS OF mom 7,100 their gods and as symbols of fair islands and islets on the western margin of the Pacific Ocean. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Philippine Culture and the Filipino Identity Miguel A. Bernad Philippine Studies vol. 19, no. 4 (1971): 573–592 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 30 13:30:20 2008 Philippine Culture and the MIGUEL A. BERNAD I N 1958 I had the privilege of visiting the island of Borneo. With me, as my companion and assistant, was a man who has since become my boss: Father Francisco Araneta. We I were guests of the Sarawak Museum, and our expenses while on the island were paid for by the Sarawak Government. Through the kindness of our hosts, and ably chaperoned by two guides- one a Muslim Malay and the other a Catholic Iban- we travelled about in two of the three northern regions of that great and mysterious island, namely in Sarawak and in Brunei. We travelled by landrover, by motorboat up the rivers into the interior, and also (leas extensively) on foot. Borneo (as is well known) is inhabited by people of many tribes or ethnic groups. -

Philippine Gay Culture 39

Philippine Gay Culture Binabae to Bakla Silahis to MSM J. Neil C. Garcia in association with The University of the Philippines Press Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Rd Aberdeen Hong Kong © J. Neil C. Garcia 1996, 2008, 2009 First published by The University of the Philippines Press in 1996, with a second edition in 2008 This edition published by Hong Kong University Press in association with The University of the Philippines Press in 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-985-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. www.hkupress.org secure on-line ordering Printed and bound by Liang Yu Printing Factory Co. Ltd., in Hong Kong, China Contents A Transgressive Reinscription ix Author’s Note for the Second Edition xi Preface xv Introduction 1 Part One Philippine Gay Culture 39 Chapter One 61 The Sixties Chapter Two 82 The Seventies Chapter Three 151 Precolonial Gender-Crossing and the Babaylan Chronicles Chapter Four 198 The Eighties Chapter Five 223 The Nineties Chapter Six 246 Prologue vii viii | Philippine Gay Culture Part Two The Early Gay Writers: Montano, Nadres, Perez 276 Chapter One 287 Where We Have Been: Severino Montano’s “The Lion and the Faun” Chapter Two 334 Orlando Nadres and the Politics of Homosexual Identity Chapter Three 361 Tony Perez’s Cubao 1980: The Tragedy of Homosexuality Conclusion 387 Philippine Gay Culture: 420 An Update and a Postcolonial Autocritique Notes 457 Bibliography 507 Index 527 Introduction That Philippine gay culture exists is an insight not very difficult to arrive at. -

Encyclopedia of the Philippines", Zoilo M

CATALOG OF LOCAL HISTORY MATERIALS ON REGION I (Serial/Periodical Articles) ABAYA, EVARISTO Evaristo Abaya. "Encyclopedia of the Philippines", Zoilo M. Galang, ed. 3 : 440, c1950 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman ABAYA, ISABELO Ilustre, Araial. The patriots of Ilocos Sur. "Samtoy", 2(3) : 19+ Jl-S 2000 Location: University of the Philippines Diliman Isabelo Abaya. "Eminent Filinos”, Hector K. Villarroel and others. : 3-4, 1965 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman Isabelo Abaya. "Encyclopedia of the Philippines", Zoilo M. Galang ed. 3 : 441, 3d ed. 1950-58 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman ABLAN, ROQUE Roque Abalan. "Eminent Filipinos”, Hector K. Villarroel and others. : 9-10, 1965 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman AGBAYANI, AGUEDO F. Coronel, Miguel. Pangasinan's Agbayani. "Weekly Nation", 7 : 13, 44 F 7, 1972, il. Location: University of the Philippines Diliman Planned development and its challenges. "Republic", 3 : 18-19+ Ja 14, 1972, il. Location: University of the Philippines Diliman Upgrading Pangasinan's economic future. "Weekly Nation", 7 : 12, 40+ F 7, 1972, il. Location: University of the Philippines Diliman AGCAOILI, ANDRES Andres Agcaoili. "Encyclopedia of the Philippines", Zoila M. Galang, ed. 17 : 10, 1958 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman AGCAOILI, JULIO Julio Agcaoili. "Encyclopedia of the Philippines", Zoilo M. Galang, ed. 3 : 441, 1950 Location: DLSU University of the Philippines Diliman AGED Da Lelong ken da Lelang. "Samtoy", 3(4) : 36-37, O-D 2001, il. Location: University of the Philippines Diliman AGLIPAY, GREGORIO LABAYEN De Achutegui, Pedro S. The Aglipayan churches and the Census of 1960. -

Barangay Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society

Scott "William H enry non ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY PRESS Contents ATF.NEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bellarmine Hall, Katipunan Avenue Loyola Hts., Quezon City Philippines P.O. Box 154, 1099 Manila, the author Copyright 1994 by Ateneo dc Manila and First printing 1994 Second printing 1995 Cover design by Fidel Rillo journals; chaptef: have been published in Philippine Earlier versions of certain chapters chapter 4 ,n PtoUppma Culture and Society (Scott 1990a); 2 in Phiimnne. Quarled) of (Scott 1992 ). chapter 5, m Kinaadman Sacra (Scott 1990b); and part of from the Codex reproduced in this book are taken Foreword ix The illustrations from the Boxer Quirino and Mauro Garcia in article on the Codex by Carlos taken from the Boxei Cod | INTRODUCTION cover illustration , orknce «7 (1958)- 325-453. For the | University of Indiana, winch gav, The Word. “Barangay " • The Word "Filipino” 9 The Filipino People Jded by the Lilly Library of the "L p 9 The Beyer Wave Migration Theory Philippine Languages permission for its reproduction. A Word about Orthography Data 1 National Library Cataloging-in-Publication PART The Visayas Recommended entry: CHAPTER 1: PHYSICAL APPEARANCE 17 Decorative Dentistry. 9 Tattooing 9 Skull Moulding 9 Penis Pins 9 9 9 9 Scott, William Henry. Circumcision Pierced Ears Hair Clothing Jewelry th-century Barangay : sixteen .35 Philippine culture and society / CHAPTER 2: FOOD AND FARMING City Rice 9 Root Crops 9 Sago • Bananas 9 Visayan Farming Terms by William Henry Scott. - Quezon Fanning 9 9 Fishing 9 Domestic Animals 9 Cooking ADMU Press, cl 994. - 1 v Camote Hunting Betel Nut 9 Distilling and Drinking 9 Drinking Etiquette 1.