Scrapper / Matt Bell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Announcing A

• . ' 10 'WEB '•STTfIPgT OST3*R, -B,' f.~ . ' I ' ' I .¦ I . 1 / - - - I -* --—== ¦¦— ¦_ ANNOUNCING A. new 8'cylinder V-type car at medium price ... Tv VIKING This week General Motors presents an en- scratch; they were not committed to any design. By E l tirely new automobile. the most grueling of tests, every phase of perform- s It is the Viking* ance was c^ec^ compared—General Motors j T . o r j r • i t i requiring only that the ultimate result meet its It is an 8-cylmder car, of iac-inch wheel • standard of quality and maximum ; i n «• i T't* i ' value—and the . , . base,’ with Bodies by t isher. , T r i J 90-degree V-type 8-cylinder engine won its place Its price is $1,595 at the factory. , I I under the viking s hood . in the factories and It is built Oldsmobile Th; bodies of the viking were designed by I sold through Oldsmobile dealers. Fisher, whose craftsmen sought distinction along 1 * * ' * * the most difficult path s the achievement of beauty i . Details will be given in the coming advertise- and elegance through simple lines. ments of the Viking. The purpose of this message General Motors is proud of the Viking and ac- is to tell briefly why and how General Motors knowledges the generous public patronage which has produced this new car. has made it possible to offer a new car of such qual- There has been a public demand for an 8-cylinder at medium price, car of General Motors quality in the medium price * * * * * field. -

Chronological Histories Olamerican Car Makers

28 AUTOMOTIVE NEWS (1940 ALMANAC ISSUE) Chronological Histories ol American Car Makers (Continued from Page 26) Chrysler Corp. “ Total Cadillac-LaSalle—Cont’d Produc- Price Year Models tion Range* Factories Milestone. Voftf (Total All Units Tkm of Cin Sales to Body Style List Mlleitonee Dealers (Typical Car) Price — Produced 1925 Maxwell 4 137,668 Maxwell 4 Touring Highland Park Chryeler Chrysler Six 5895 to Chrysler Newcastle automotive design andfj 6.000,000 tooling rearrangement Six Sedan $2065 Evansville time In 1932 V-S LaS. J45-B 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2.645 Over spent for and Jew, the V-8 366-B 9,253 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 3.095 for complete line of new models. Super-safe head- fig g; 3,796 on Cadillac cars. Aircooled Kercheval compression engines safety’ V-12 370-B 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) lights first introduced Dayton bodies, JS V-16 462-B 5-P. Sedan 5,095 generator; completely silent transmission; full range air cleaners equipment. Chrysler Corp. organizedanJh3*?* • ride regulator. Wire wheels standard "i"*” iHM?' 1933 V-8 LaS. 346-C 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2,495 v-16 production restricted to 400 cars. Fisher no-draft asraaray V-8 356-C 6,839 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 2.995 ventilation. LaSalle first American made car with Cn -* V-12 370-C 5-P. Town sedan (trunk) 1.685 spare tire concealed within body. sxxir«. s V-16 452-C 5-P. Fleetwood sedan B^so Coupe) to supply Chrysler 58 170.392 Chrysler 58 Touring Highland Pork Introduced rubber 1834 Str. -

Car Owner's Manual Collection

Car Owner’s Manual Collection Business, Science, and Technology Department Enoch Pratt Free Library Central Library/State Library Resource Center 400 Cathedral St. Baltimore, MD 21201 (410) 396-5317 The following pages list the collection of old car owner’s manuals kept in the Business, Science, and Technology Department. While the manuals cover the years 1913-1986, the bulk of the collection represents cars from the 1920s, ‘30s, and 40s. If you are interested in looking at these manuals, please ask a librarian in the Department or e-mail us. The manuals are noncirculating, but we can make copies of specific parts for you. Auburn……………………………………………………………..……………………..2 Buick………………………………………………………………..…………………….2 Cadillac…………………………………………………………………..……………….3 Chandler………………………………………………………………….…...………....5 Chevrolet……………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chrysler…………………………………………………………………………….…….7 DeSoto…………………………………………………………………………………...7 Diamond T……………………………………………………………………………….8 Dodge…………………………………………………………………………………….8 Ford………………………………………………………………………………….……9 Franklin………………………………………………………………………………….11 Graham……………………………………………………………………………..…..12 GM………………………………………………………………………………………13 Hudson………………………………………………………………………..………..13 Hupmobile…………………………………………………………………..………….17 Jordan………………………………………………………………………………..…17 LaSalle………………………………………………………………………..………...18 Nash……………………………………………………………………………..……...19 Oldsmobile……………………………………………………………………..……….21 Pontiac……………………………………………………………………….…………25 Packard………………………………………………………………….……………...30 Pak-Age-Car…………………………………………………………………………...30 -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

Nominations for Occ/Bod & Members 2001-02 Nominating

The Options Clearing Corporation #14766 BackTO: to InfomemoALL CLEAR SearchING MEMBERS FROM: James C. Yong, First Vice President, Deputy General Counsel and Secretary DATE: December 28, 1999 SUBJECT: NOMINATIONS FOR THE OPTIONS CLEARING CORPORATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND MEMBERS OF THE 2001-2002 NOMINATING COMMITTEE Please be advised that the Nominating Committee will meet on January 26, 2000 at the offices of OCC. At the meeting, the Committee will nominate (i) three candidates for election as Member Directors of OCC for a three-year term ending in April, 2003, and (ii) three candidates for election as members of the Nominating Committee for a two-year term ending in April, 2002. The Nominating Committee will consider potential candidates proposed by Clearing Members. Please note that in order to be qualified for election either as a Member Director or as a member of the Nominating Committee, a candidate must be a Designee of a Clearing Member. A list of Clearing Member Designees is attached. Please forward the name of any Designee you would like to propose for election as a Member Director or a Member of the Nominating Committee either to: James C. Yong Secretary The Options Clearing Corporation 440 S. LaSalle Street, Suite 2400 Chicago, IL 60605 or to the members of the 2000-2001 Nominating Committee. For your convenience, the name and address of the members of the 2000-2001 Nominating Committee are: Norman R. Malo Dennis J. Donnelly National Financial Services Corporation McDonald Investments, Inc. 200 Liberty Street 800 Superior Avenue New York, NY 10281 Cleveland, OH 44114 James C. -

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs ACD Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club www.acdclub.org AACA Antique Automobile Club of America www.aaca.org BMW BMW Car Club of America www.bmwcca.org CCCA Classic Car Club of America [email protected] CCA Corvette Club of America, www.vette-club.org FCA Ferrari Club of America www.ferrariclubofamerica.org GOOD-GUYS Good-Guys Hotrod Association www.good-guys.com HCCA Horseless Carriage Club of America www.hcca.org HHRA National Hotrod Association www.nhra.com MBCA Mercedes-Benz Club of America www.mbca.org MCA Mustang Club of America www.mustang.org NMCA National Muscle Car Association www.nmcadigital.com NSRA National Street Rod Association www.nsra-usa.com PCA Porsche Club of America www.pca.org RROC Rolls-Royce Owners Club www.rroc.org SCCA Sportscar Club of America www.scca.com SVRA Sportscar Vintage Racing Association www.svra.org VMCCA Veteran Motor Car Club Of America www.vmcca.org VCCA Vintage Car Club of American www.soilvcca.com VMC Vintage Motorsports Council www.the-vmc.com VSCCA Vintage Sports Car Club of America www.vscca.org VCA Volkswagen Club of America www.vwclub.org SINGLE MARQUE: AUTOS AC AC Owners Club http://acowners.club ALFA ROMEO Alfa Romeo Owners Club http://www.aroc-usa.org ALLARD Allard Owners Club www.allardownersclub.org ALVIS North American Alvis Owners Club http://www.alvisoc.org AMC American Motors Owners Association www.amonational.com AMERICAN AUSTIN/BANTAM American Austin/Bantam Club www.austinbantamclub.com AMPHICAR International Amphicar Owners Club www.amphicar.com AUBURN/CORD/DUESENBERG Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club http://www.acdclub.org AUSTIN-HEALEY Austin-Healey Club of America http://www.healeyclub.org AVANTI Avanti Owners Association International, www.aoai.org BRICKLIN Bricklin International Owners Club www.bricklin.org BUGATTI American Bugatti Club, http://www.americanbugatticlub.org BUICK Buick Club of America www.buickclub.org CADILLAC Cadillac and LaSalle Club, www.cadillaclasalleclub.org CHECKER Checker Car Club of America www.checkerworld.org CHEVROLET American Camaro Assoc. -

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

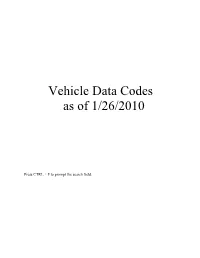

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

Club Racing Media Guide and Record Book

PLAYGROUND EARTH BEGINS WHERE YOUR DRIVEWAY ENDS. © 2013 Michelin North America, Inc. BFGoodrich® g-ForceTM tires bring track-proven grip to the street. They have crisp steering response, sharp handling and predictable feedback that bring out the fun of every road. They’re your ticket to Playground EarthTM. Find yours at bfgoodrichtires.com. Hawk Performance brake pads are the most popular pads used in the Sports Car Club of America (SSCA) paddock. For more, visit us at www.hawkperformance.com. WHAT’SW STOPPING YOU? Dear SCCA Media Partners, Welcome to what is truly a new era of the Sports Car Club of America, as the SCCA National Champi- onship Runoffs heads west for the first time in 46 years to Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca. This event, made possible with the help of our friends and partners at Mazda and the Sports Car Rac- ing Association of the Monterey Peninsula (SCRAMP), was met with questions at its announcement that have been answered in a big way, with more than 530 drivers on the entry list and a rejunvenaton of the west coast program all season long. While we haven’t been west of the Rockies since River- side International Raceway in 1968, it’s hard to believe it will be that long before we return again. The question on everyone’s mind, even more than usual, is who is going to win? Are there hidden gems on the west coast who may be making their first Runoffs appearance that will make a name for themselves on the national stage, or will the traditional contenders learn a new track quickly enough to hold their titles? My guess is that we’ll see some of each. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name West Loop - LaSalle Street Historic District other names/site number 2. Location Roughly bounded by Wacker Drive, Wells Street, Van Buren Street street & number and Clark Street N/A not for publication N/A city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois code IL county Cook code 031 zip code 60601-60604 60606, 60610 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Rocket Review Fall Super Edition

The Official Publication of The Capitol City Rockets July/Aug/Sept 2007 Volume 18, Issue 4 Scott Phillips—Editor The Rocket Review Fall Super Edition The 2007 All- GM Show held at Mont- gomery Col- Inside this issue: lege in Rock- ville proved to be as excel- Gary Sutherlin’s Travels 2-3 lent as the Local/National Calendar weather. All-GM Wrap Up and 4 More photos Results inside! Ken Quincy’s ‘84 All-GM Show Pictures 5-8 H/O is front and center. Classifieds/Directory and 9-10 Membership All-GM Show Breakdown—Cory Correll To all CCR members, high tech vote tabulation of Many folks drove 1.5 miles Club Events: Everyone wants to Denney Keys, Ken Quincy, to O‟Brien‟s restaurant for thank all the hard workers and Richard Brown. Rick lunch and then came back! Save these and non-member volunteers Merry and his Austrian We will be entertaining Dates: that helped make our annual guest, Gary, did an out- other food vendors for next All-GM show another suc- standing job with the t-shirt year. The new DJ proved Sat, Oct 20, cess this year. Our show is sales. Jim, Jr. and his popular, and we sold a lot of continually getting some daughter Rebecca helped shirts due in part to less 8:30 am-4 pm, concourse-class antique iron Jim and Blanca with the vendor competition this Rockville An- to show up, and I never fail Metro “Carbucks” refresh- year. to be impressed with the ment stand. There were tique and Classic I was told by many quality of the cars. -

Sallee Speaks

Number 36 Volume 13 No 4 October 2017 Sallee Speaks Geoff Pollard’s 37 Coupe, Victoria, Australia, refer rebuild in Para 6a) below Newsletter of the LaSalle Appreciation Society A Chapter of the Cadillac & LaSalle Club Inc. LAS No 36 Oct 2017 I suppose after the sad news I should 1. Director’s Speak give good news. The Grand National was Hello Fellow Sallyites, great fun, there were a number of LaSalles in attendance, and I was able to Just days after the last issue of Sallee speak to many of the members and a few Speaks hit the streets I received a phone who were not. Since I was judging and call on my voice mail from a highly Nancy was hosting the ladies tea and respected Cadillac- LaSalle member. fashion show, Bud and Barbara Coleman Many of you will not know his name but I ran the meeting and provided the can assure you if it wasn’t for Norm Uhlir minutes that appear elsewhere in this there would be no Cad-LaSalle Club. issue. Thank you to the Colemans for Norm Uhlir is one of the three or so covering for us. Editor John tells me that people who conceived the idea of an pictures of the LaSalles at the Grand antique car club dedicated to Cadillacs National will appear over the next few and LaSalles back in 1958 when I was issues. Chairman Ronnie Hux organized still in high school. Norm’s name remains an impressive array of activities, from on the Regional Activities Award given bus tours to a Friday night ‘Flash Back every year at the Grand National Meet to Friday’ dance party with Valley Forge any region in the U.S.A. -

WJBC Radio Collection

1 McLean County Museum of History WJBC Radio Collection Processed by Valerie Higgins Summer 2007 Reprocessed by Michael Kozak Spring 2008 Table of Contents Collection Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Folder Inventory COLLECTION INFORMATION Volume of Collection: Eight Boxes. Collection Dates: 1924-2000. Restrictions: Some brittle documents. Use photocopies unless authorized by Librarian / Archivist. Reproduction Rights: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History. Location: Archives Notes: For additional information, see: WJBC Radio Subject Photograph Collection. 2 Historical Sketch Shortly after graduating from high school in 1924, Lee Stremlau of LaSalle and several of his friends began making unlicensed radio broadcasts from the Hummer Furniture Store in LaSalle, Illinois. They persuaded Wayne Hummer to apply for a license to broadcast, and they were granted one by U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover in the name of the Hummer Furniture Company in 1925. They were given permission to broadcast at 100 watts at a wavelength of 1280 kilocycles and were assigned the call letters WJBC. Stremlau used the letters to create the slogan “Where Jazz Becomes Classic” for the radio station and his business, Lee Stremlau’s Radio and Victrola Shop. The inaugural broadcast, which included a speech by the mayor of the city, was praised in the May 5, 1925 edition of a LaSalle paper, which reported that the Hummer store was flooded with calls congratulating the entrepreneurs. In the next few years, the Federal Radio Commission would reassign WJBC to a new wavelength twice, first to 1320 kilocycles in 1927, on which they shared time with stations WWAE and WCLO, and then to 1200 kilocycles, shared with WJBL, a year later.