Their Language of Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

Out of Sight*

ikramullah Out of Sight* It was an august afternoon. The sun, lodged in a sky washed clean by the rain, stared continuously at the world with its wrathful eyes. By that time, the traffic had died down and the main bazaar of the town of Sultan- pur had become completely deserted. The pitch-black road lying senseless in the middle of the bazaar, soaking wet with perspiration, had taken on an even darker hue. The shopkeepers sat quietly in their shops behind awnings fastened to bamboo poles extending out to the road. What wretch would leave his house in such weather to go shopping? Sitting on the chair inside his shop, Ismail saw his friendís eight- or ten-year-old son Mubashshir pass by under his awning, walking backwards with a satchel around his neck. A smile suddenly appeared on Ismailís face. Kids will be kids, he thought. Feeling bored and alone since he couldnít find anything to interest him, he had devised this private pastime of walking home backwards. Ismail called him over: ìHey Mubashshir, come here!î ìComing Baba Ji,î saying that, the boy climbed the two wooden-plank stairs and stood facing Ismail. His demeanor showed respect and his won- dering eyes were asking, ìWhatís the matter?î ìWhy are you walking backwards? Want to bump into some bicyclist or pedestrian?î ìNo, Baba Ji, Iím careful. Every now and then I turn around to look.î ìDonít act silly. Walk straight up the road, face forward. Do you understand?î The boy said yes, and as he started going down the two steps Ismail asked, ìIs your father back from Lahore yet?î ìNo. -

EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Artefacts Available for Loan

EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Artefacts available for loan WOLVERHAMPTON LIBRARIES EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Parkfield Centre Wolverhampton Road East Wolverhampton WV4 6AP Tel: 01902 555907 Email: [email protected] OPENING HOURS Monday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 6:00 Tuesday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Wednesday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Thursday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Friday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 4:30 The resources detailed in this booklet are available to loan by teachers and other educationalists whose schools have bought in to the Education Library Service Level Agreement. Resources are available to be booked in advance. Please telephone or email any booking requests. 1 Religion Christianity: Easter TK 200 Pt.1 Contents: 1 Crucifix 1 Cross of the risen Christ 1 Paschal Candle 3 Palm crosses 1 Gold Cloth (“Colour for Easter”) 1 Booklet – “Easter and Holy Week” 1 Stations of the Cross booklet 2 Easter cards 3 Posters – The Easter Story, Easter Eggs and An Easter table 1 Hot cross bun – varnished 1 Decorated tin egg (2 parts) 4 Laminated A4 sheets Easter candle + description Palm cross + description 2 Christianity: Christmas TK 200 Pt.2 Contents: 1 Candle 1 Mince Pie (plastic) 1 Mistletoe 1 Holly 1 Nativity Scene 3 Christianity: Christmas TK 200 Pt.3 Contents: 6 Christmas Cards 1 Nativity Crib with Figures and Light 1 White Stole 1 Advent Candle 1 Advent Calendar 1 Fabric for Display Drape 1 Music CD 3 Wise Men – Russian Figures 3 Wise Men in Straw from Czech Republic 1 Icon – Madonna and Child 1 Stained Glass with Christmas Story 1 Book – Christmas Story 1 Christmas Book – Activities for Pupils and Notes for Teachers 4 Christianity: Prayer and Devotion TK 200 Pt.4 Contents: 1 Rosary 1 Thurible 1 Incense Pot 1 Bag of Incense 2 Charcoal Bricks 2 Votive Candles 4 Icons – Madonna and Child Last Supper Our Lord Virgin Mary 1 Bible 1 New Testament and Psalms 1 Book of Common Prayer 1 Lectionary 1 Booklet – “The Baptists” 5 Christianity: Rites of Passage TK 200 Pt.5 Contents: 1. -

Sikh Religion and Islam

Sikh Religion and Islam A Comparative Study G. S. Sidhu M.A. Gurmukh Singh Published by: - © Copyright: G. S. Sidhu and Gurmukh Singh No. of Copies: Year Printer: ii INDEX ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS BOOK ........................................ 1 MAIN ABBREVIATIONS:........................................................................... 1 SOURCES AND QUOTATIONS .................................................................. 1 QUOTATIONS FROM THE HOLY SCRIPTURES ........................................... 2 SIKH SOURCES ..................................................................................... 2 ISLAMIC SOURCES ................................................................................. 2 FOREWORD .................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 1 ..................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 6 1.1 THE NEED FOR RELIGION ........................................................ 6 1.2 THE NEED FOR THIS STUDY ..................................................... 7 1.3 SIKHISM AND ISLAM: INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS ................... 11 CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................... 14 APPROACHES .............................................................................. 14 2.1 SIKHISM .............................................................................. -

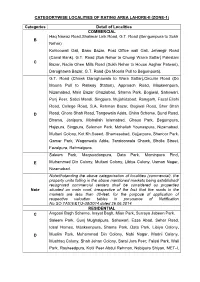

Categorywise Localities of Rating Area Lahore-Ii (Zone-1)

CATEGORYWISE LOCALITIES OF RATING AREA LAHORE-II (ZONE-1) Categories Detail of Localities COMMERCIAL Haq Nawaz Road,Shalimar Link Road, G.T. Road (Bengumpura to Sukh B Nehar) Kohloowali Gali, Bano Bazar, Post Office wali Gali, Jehangir Road (Canal Bank), G.T. Road (Suk Nehar to Chungi Warra Sattar) Pakistani C Bazar, Nadia Ghee Mills Road (Sukh Nehar to House Asghar Patwari), Daroghawla Bazar, G.T. Road (Do Mooria Pull to Begumpura). G.T. Road (Chowk Daroghawala to Wara Sattar),Circular Road (Do Mooria Pull to Railway Station), Approach Road, Maskeenpura, Nizamabad, Main Bazar Ghaziabad, Shama Park, Bogiwal, Sahowari, Punj Peer, Sabzi Mandi, Singpura, Mujahidabad, Ramgarh, Fazal Ellahi Road, College Road, S.A. Rehman Bazar, Bogiwal Road, Sher Shah D Road, Ghore Shah Road, Tangewala Adda, China Scheme, Bund Road, Bhama, Janipura, Mohallah Islamabad, Ghaus Park, Begumpura, Hajipura, Singpura, Suleman Park, Mohallah Younaspura, Nizamabad, Multani Colony, Kot Kh.Saeed, Shamasabad, Gujjarpura, Shanoor Park, Qamar Park, Wagonwala Adda, Tandoorwala Chowk, Bholla Street, Fazalpura, Rehmatpura. Saleem Park, Maqsoodanpura, Data Park, Mominpura Pind, E Muhammad Din Colony, Multani Colony, Libiya Colony, Usman Nagar, Nizamabad. Notwithstanding the above categorization of localities (commercial), the property units falling in the above mentioned markets being established/ recognized commercial centers shall be considered as properties Note situated on main road, irrespective of the fact that the roads in the markets are less than 30-feet, for the purpose of application of respective valuation tables in pursuance of Notification No.SO.TAX(E&T)3-38/2014 dated 26.06.2014. RESIDENTIAL C Angoori Bagh Scheme, Inayat Bagh, Mian Park, Surraya Jabeen Park. -

Village Survey of Brahmaur, Part-VI-No-5,Vol-XX, Himachal Pradesh

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XX - PART VI -- No.5 HIMACHAL PRADESH A Village Survey of BRAHMAUR Brahmaur Sub-Tehsil, Chamba District Investigation & Draft by DHARAM PAL KAPUR Guidance and Final Draft by RIKHI RAM SHARMA Assistant SUl'erintendent of Census 01'erations Editor RAM CHANDRA PAL SINGH of the Indian Administrative Service Superintendent of Census Operations ~ OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR " GENERAL, INDIA, NEW DElHI. 2011 [LIBRARY] Class No._' t 315.452 \ Book NO._1 1961 BRA VSM i , 44121 Accession N I J CONTENTS FOREWORD III PREFACE VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VIII I THE VILLAGE 1 tlztroduction.--Physical Aspects-Configuration-Geology, Rock and Soil-Flora-Fauna-Water Supply-Size-Market .and Administrative Institutions-History, 2 THE PEOPLE AND THEIR MATERIAL EQUIPMENT 12 Caste Composition-Housing Pattern-Dress-Ornaments Household Goods-Food Habits-Utensils-Birth Customs Marriage Customs-Death Rites. 3 ECONOMY 35 Economic Resources-Workers and Non·workers-Agricul~ ture-Horticulture-Animal HlisbandrY-Malundi and Pohals and their Migration Calendar-Village Crafts-Income Expenditure-Indebtedness and Mortgages. 4 SOCIAL AND CULTURAL LIFE 53 Migration-Religion-Temples-Fairs and Festivals-Folk Dances-Folk Songs-Amusements-Beliefs and Superstitions -~tatus of Women-Un touch ability-Inheritance-Language. 5 PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS 71 Education-Public Health and Sanitation-Community Deve [opment-Cooperatives-Panchayats-Conc[usion. L/P(D)4SCOHP-4(a) n CONTENTS APPENDICES ApPENDIX I-Extracts from Antiquities of Chamba, Volume I, by J. Ph. Vogel, Superintendent, 4rchaeological Sur vey, Northern Circle 79 APPENDIX II-Extracts from the Punjab States Gazetteer, Vol. XXII A, Chamba State, 1904 (pp. 261-266), by Dr. Hutchinson' .of the Church ,of Scotland Mission, Chamba ".~. -

Punjabi Sanatam Dharam Wedding

Some common surnames: Malhotra Chawla Wadhwa Singh Kapoor Khanna Dhawan Arora Punjabi Sanatam Dharam Wedding INTRODUCTION TO A TYPICAL NORTH INDIAN WEDDING The North Indian community is known for having lavish festivals and weddings. Their wedding preparations begin well in advance and the ‘sangeet’ parties have become elaborate occasions lasting almost for a week sometimes! The bridegroom generally mounts a richly caparisoned mare and his ‘baraat’ (procession) is replete with a live band; relatives and friends accompanying him sing and dance all the way to the wedding venue! Families exchange lavish gifts all throughout the marriage ceremonies. Their weddings are usually held in hotels or banquet halls and in cities like New Delhi huge ‘shamianas’ (decorative tents) are erected in parks to host the wedding ceremonies and quite often, the reception. PANJABI SANATAN DHARAM WEDDING 1. ROKNA OR THAKA: Acceptance of the alliance In the olden days most North Indian weddings were practically arranged by the local barber. He would be responsible for gathering details of the family, namely the background, the financial status and above all the ‘gotra’ or ancestory. Once the families were in agreement a small ceremony called the ‘shagun’ or ‘rokna’ or ‘thaka’ would be held in the presence of very close relatives, where as a token the elders would exchange a small amount of Rs. 1.25! ‘Rokna’ is an important part of the North Indian wedding although the ‘shagun’ now could be any amount of money – instead of the customary Rs. 1.25, which was so common in the olden days. Requirements: 11,21.31,or 51 Sweet Boxes Dry Fruits Cash gifts for groom Seasonal fruits Clothes for the groom 2. -

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE for RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17Th, 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: LAHORE, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Lahore District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionR ajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations (http://www.lahorepolice.gov.pk/) Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 9,396,398 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99230660 Male 4,949,706 (53%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 SP Iqbal Town Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99233331 Tapas urban populated Female 4,446,692 (47%) 3 Iqbal Town 0092 42 37801375 DISTRICT 22 213 360 211 92 40 17 4 SP Saddar Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99262023-4 Rural 1,650,134 (18%) LAHORE CITY 10 76 115 51 40 15 9 Urban 7,746,264 (82%) LAHORE 5 SP Saddar Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092 42 99262028-7 12 137 245 160 52 25 8 Tehsils 2 CANTT 6 Johar Town 0092 42 99231472 Towns & Cantonment 9 & 1 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 7 SP Cantt. Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99220615/ 99221126 UC 165 8 SP Cantt. Div. (Inv. Wing) 0092-52-3553613 Road Network Infrastructure: District Roads: 1,244.41 (km), NHWs: 48.43 (km), Prov. Highways: Revenue Villages/Mouza 360 9 SP Model Town Div. (Ops. Wing) 0092 42 99263421-2 113.6 (km) R&B Sector: 245.31 (km), Farm to Market: 343.47 (km), District Council Roads: 493.6 (km) 10 SP Model Town (Inv. -

Title Items-In-Peace-Keeping Operations - India/Pakistan - Secretary-General's Representative on the Question of Withdrawal of Troops

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 34 Date 30/05/2006 Time 9:39:27 AM S-0863-0003-08-00001 Expanded Number S-0863-0003-08-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - India/Pakistan - Secretary-General's representative on the question of withdrawal of troops Date Created 24/08/1965 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0863-0003: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant: India/Pakistan Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit UNITED STATIONS Press Services Office of Public Information United Nations, N.Y. (FOR USE OF INFORMATION MEDIA — NOT AH OFFICIAL RECORD) Press Release KASH/131 £4 August 1965 l ' STATEMENT ST.SEE SECTARY-C-MERALON; TEE YJMOWIi SITUATION \ "As already indicated, I am greatly concerned about the situation in Kashmir. It poses a very serious ana dangerous threat to peace. "Therefore, in the course of the past two waeks, I have been in earnest confutation with the peraianent representatives cf the two Governments with a view to stopping the violations o£ the cease-fire line which have been reported to me by General ITimmo, Chief Military Observer of UHMOGIP,* and effecting a restoration of normal conditions along the cease-fire line. "la the same context I have had in mind the possibility of sending urgently a Personal Representative to the area for the purpose of meeting and talking with appropriate authorities of the two Governments and with General Mmmo, and conveying to the Governments my very serious concern about the situation and exploring with them ways and means of preventing any further deterioration in that situation and restoring quiet along the cease-fire line. -

Supplementary 2010

GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGET S T A T E M E N T For 2010-2011 I SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGET STATEMENT 2010 - 2011 SUMMARY BY DEMANDS Reference to Demand Grant Name of Demand Rs. pages Number Number I. Supplementary Demands (Voted) 1 - 4 1 2 Land Revenue 371,515,000 5 - 13 2 5 Forests 248,986,000 14 - 22 3 6 Registration 7,615,000 23 - 24 4 7 Charge on Account of Motor Vehicle Acts. 1,951,000 25 - 27 5 8 Other Taxes and Duties 65,580,000 28 - 38 6 9 Irrigation & Land Reclamation 3,460,447,000 39 - 46 7 12 Jails & Convict Settlements 149,314,000 47 - 82 8 13 Police 2,340,807,000 83 - 84 9 14 Museums 8,934,000 85 - 92 10 17 Public Health 137,838,000 93 - 110 11 18 Agriculture 262,639,000 111 - 112 12 19 Fishries 69,217,000 113 - 115 13 21 Cooperations 21,332,000 116 - 121 14 22 Industries 163,195,000 122 - 137 15 23 Miscellaneous Departments 192,933,000 138 - 145 16 24 Civil Work 801,042,000 146 - 154 17 25 Communications 1,836,741,000 155 - 160 18 27 Relief 7,224,895,000 161 - 161 19 28 Pension 7,803,856,000 162 - 163 20 29 Stationary & Printing 7,902,000 164 - 205 21 31 Miscellaneous 429,593,000 206 - 206 22 32 Civil Defence 4,040,000 207 - 207 23 34 State Trading in Medical Store & Coal 2,113,000 208 - 209 24 38 Agricultural Improvement & Research 689,000 II SUPPLEMENTARY BUDGET STATEMENT 2010 - 2011 SUMMARY BY DEMANDS Reference to Demand Grant Name of Demand Rs. -

Barber (Rejected)

POST s.r # NAME FATHER NAME FORM# APPLIED QUOTA CNIC # DATE O/B AGE ADDRESS EDUCATION DISTRICT FOR 1 M AZAM M KHALID 183 BARBER OPEN MERIT 34502-4470103-1 15.06.1993 P/O SHAMMAL TEHSIL SHAKARGARH NAROWAL NAROWAL 2 M MUSTAFA M AMEER 224 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201-3884916-1 01.04.1991 ST#11 MAST IQBAL ROAD GENERAL HOSPITAL LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 3 M ZESHAN ABDUL HAMEED 242 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35202-1491539-5 03-06-90 H#4 STR3 SHADRA LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 4 SAEED RASHED ABDUL RASHEED 243 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201-2204548-5 06-05-90 H#20 STR12 SHADI PURA LAHORE MATRIC LAHORE 5 M SABIR NAZWAZ ALI 283 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201-9663842-7 20-6-1988 H#231 STR# 2A FAISAL PARK LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 6 M KHALID YOSIF 383 BARBAR OPAN MERIT 35202-2273250-7 14.09-1990 MANGA MANDI LAHORE NILL LAHORE 7 M ZUBAIR ALI ARIF ALI 636 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201-182462-5 16-12-88 H# E 252 MIAN MEER COLONY LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 8 M SAROSH AKBAR DIN 770 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35401-533924-3 13-04-93 21/4 MALIK PARK RACHNA TOWN FEROZWALA SHAHDRA SKP B.A SKP 9 ASAD ALI BARKAT ALI 818 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35205-0370756-9 11.11.1989 ATTOKE AWAN BUATAPUR LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 10 AROOSH LAIQ JAVED MASIH 881 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201-1275465-5 01.01.1991 GARHI SHAHU LAHORE MIDDLE LAHORE 11 SULTAN MEHMOOD ZAFAR IQBAL 933 BARBER OPEN MERIT 34502-8703176-1 01.09.1995 SHAKARGHAR, NAROWAL MIDDLE NAROWAL 12 ABDUL REHMAN M GULZAR 1298 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35202-0108309-9 01-01-89 AWAN TOWN LAHORE MIDDLE BAHWAL NAGAR 13 MUHAMMAD NABEEL ASIF MUHAMMAD ASIF 2106 BARBER OPEN MERIT 35201.2393871.1 20.07.1990 SALAMT -

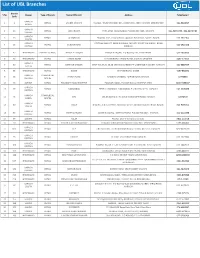

To Download UBL Branch List

List of UBL Branches Branch S No Region Type of Branch Name Of Branch Address Telephone # Code KARACHI 1 2 RETAIL LANDHI KARACHI H-G/9-D, TRUST CERAMIC IND., LANDHI IND. AREA KARACHI (EPZ) EXPORT 021-5018697 NORTH KARACHI 2 19 RETAIL JODIA BAZAR PARA LANE, JODIA BAZAR, P.O.BOX NO.4627, KARACHI. 021-32434679 , 021-32439484 CENTRAL KARACHI 3 23 RETAIL AL-HAROON Shop No. 39/1, Ground Floor, Opposite BVS School, Sadder, Karachi 021-2727106 SOUTH KARACHI CENTRAL BANK OF INDIA BUILDING, OPP CITY COURT,MA JINNAH ROAD 4 25 RETAIL BUNDER ROAD 021-2623128 CENTRAL KARACHI. 5 47 HYDERABAD AMEEN - ISLAMIC PRINCE ALLY ROAD PRINCE ALI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.131, HYDERABAD. 022-2633606 6 46 HYDERABAD RETAIL TANDO ADAM STATION ROAD TANDO ADAM, DISTRICT SANGHAR. 0235-574313 KARACHI 7 52 RETAIL DEFENCE GARDEN SHOP NO.29,30, 35,36 DEFENCE GARDEN PH-1 DEFENCE H.SOCIETY KARACHI 021-5888434 SOUTH 8 55 HYDERABAD RETAIL BADIN STATION ROAD, BADIN. 0297-861871 KARACHI COMMERCIAL 9 65 NAPIER ROAD KASSIM CHAMBERS, NAPIER ROAD,KARACHI. 32775993 CENTRAL CENTRE 10 66 SUKKUR RETAIL FOUJDARY ROAD KHAIRPUR FOAJDARI ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.14, KHAIRPUR MIRS. 0243-9280047 KARACHI 11 69 RETAIL NAZIMABAD FIRST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD, P.O.BOX NO.2135, KARACHI. 021-6608288 CENTRAL KARACHI COMMERCIAL 12 71 SITE UBL BUILDING S.I.T.E.AREA MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI 32570719 NORTH CENTRE KARACHI 13 80 RETAIL VAULT Shop No. 2, Ground Floor, Nonwhite Center Abdullah Harpoon Road, Karachi. 021-9205312 SOUTH KARACHI 14 85 RETAIL MARRIOT ROAD GILANI BUILDING, MARRIOT ROAD, P.O.BOX NO.5037, KARACHI.