Out of Sight*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monthly Journal Devoted to Oriental Philosophy, Art, Literature and Occultism:· Embracing Mesmerism, Spiritualism, and Other Secret Sciences

A MONTHLY JOURNAL DEVOTED TO ORIENTAL PHILOSOPHY, ART, LITERATURE AND OCCULTISM:· EMBRACING MESMERISM, SPIRITUALISM, AND OTHER SECRET SCIENCES. .. VOL. 4. No.8. MADR.AS, MAY, 1883. ?olumns, in order that justice be strictly dealt out j but l~ ra~he}' proceeds to have the M8S. handed to it for pub. lIcatlOn, opened, and carefully read before it can consent 'l'HERE IS NO REIJIGION HIGHER THAN TRUTH. to send it over to its printers. Anable article has never [Family motto of the lIfaharajahs of Benares. ] sought admission into our pages and been rejected for its advocating any of the religious doctrines or views to -J- which its conductor felt personally opposed. On the TO TIlE" DISSATISF'IED." other hand, the editor has never hesitated to give any olle of the above said religions and doctrines its dues, WE have belief in the fitness and usefulness of impar and speak out tho truth whether it pleased a certain fac tial critici1:llll, and, even at time1:l, in that of a judicious tion of its sectarian reader:s) or not. \Ve neither court onslaught upon some of the many creeds and philoso nor claim favonr. N or to satisfy the sentimental emo-· phies, as we have in advocating the publication of all tions and susceptibilities of some of ollr readers· do we such polemics. Any sane man acquainted with human feel prepared to allow our columns to appeal' colourless, nature, must see that this eternal" taking on faith" of least of all, for fear that our own house should be shown the lllost absurdly conflicting dogmas in our age of as 'also of glass.' " scientific progre1:ls will never do, tlH1t it is impossible • that it can last . -

Sikhism Originated with Guru Nanak Five Centuries Ago. from an Early Age He Showed a Deeply Spiritual Character

Sikhism originated with Guru Nanak five centuries ago. From an early age he showed a deeply spiritual character. He broke away from his family’s traditions and belief systems, refusing to participate in empty rituals. Nanak married and entered business, but remained focused on God and meditation. Eventually Nanak became a wandering minstrel. Guru Nanak travelled far and wide teaching people the message of one God who dwells in every one of His creations and constitutes the eternal Truth. He composed poetry in praise of one God, and set it to music. He rejected idolatry, and the worship of demigods. He spoke out against the caste system and he set up a unique spiritual, social, and political platform based on equality, fraternal love, goodness, and virtue. Gurunanak When & Where Born Nanak was born to Kalyan Chand Das Bedi, popularly shortened to Mehta Kalu, and Mata Tripta on 15 April 1469 at Rāi Bhoi Kī Talvaṇḍī (present day Nankana Sahib, Punjab, Pakistan) near Lahore. Brief Life History of Guru Nanak His father was the local patwari (accountant) for crop revenue in the village of Talwandi. His parents were both Hindus and belonged to the merchant caste. At the age of around 16 years, Nanak started working under Daulat Khan Lodi, employer of Nanaki's husband. This was a formative time for Nanak, as the Puratan (traditional) Janam Sakhi suggests, and in his numerous allusions to governmental structure in his hymns, most likely gained at this time. Commentaries on his life give details of his blossoming awareness from a young age. At the age of five, Nanak is said to have voiced interest in divine subjects. -

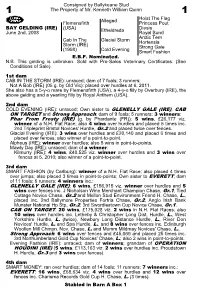

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Ari Trocou De Advogado Às De Seu Julgamento Fésperas ANGELA AQUIS MMM IÇÕES DE

¦r:r*~mifô&*.y *imç strt^ir^-^-r^r-i^rf1''^ '^% ?*f vi *r**g^-ft ^r^mí,rmvr^i^r i... q^rqyi f rf^gi» BIBUOTEOA NlOIONATj ^VB|M AVENIDA RIO BRÀNUO i.l.u tíbkJ-iiftiiàwkl.k CAPITAR jg-apsai»^ «B^a^S»»^^ ¦mnMSKO SAMBENTA DCS ÚLTIMOS FOCOS REBELDES NO PANAMÁ i TEi.rnRAMA taciiía i il tim 'illi tu llilWpppifWÉ^ séEaBBaKrBtçí-i- wsheesekb^(i.K.iA na 7) wmm^ÉÉàiismmàm^Ê CVIldUU«sa ra n ^si ww v* ^^ cll'¦w ¦ ¦ ¦ ¦ 0^r ¦ iUH.0^j w*» V ¦ ^% oipe de Estado USBQft, 7 (UPI — Urgente) — 0 ministro h Inferior, sr. Arnaldo Sclwhi, revBÍou /loje rjue foi fri/sfnvfif. orno tentativa r/e revolução em Porfugoí «o iiièí êe iiifíiço último. Acrescentou o ministro que no ocasião íornm dctnlns 31 pes- sooj, sendo 22 civis e 9 militares, Mais detalhes na pc/ginci 7. •-^affiaraaçsBí SJER^ RÊV/V/DO 0 ASSASSifilO Dl HILWA AMOROSO "liai "barbudo" mais As dos lunins brasileira e cubano tini charuto ann" r n lnlrr funil ba- tiniir. n tinina idealista rir Fidel Castro estere qualidades foram dn Cas- comparadas ontem na nlntfiçn oferecido pelo presiden- /oradas dr um nutro ctiointn baiano, Este Ini um dos acesa dr, 71/e nunca nn i-ntnírin da Esplanada as o te Juscelino Kubitschek no primeiro ministro Fuiri muitos aspertn-, pitorescos observados livremente peln-, Irh durante o qual taram relembrados causas durante 00 minutos. Ari Trocou de Advogado às Castra, quando o chefe do gorcrno brasileira fumou jornalistas no almoço tio Palácio dns Laranjeiras, A efeitos da derrubado de. -

CLASSIC...Albert the Great(Go for Gin), Who Will Be Trying to End a Three-Race Los- Ing Streak When He Starts in the Classic, Br

Tuesday, Thoroughbred Daily News October 23, 2001 TDN For inform ation, call (732) 747- 8060. HEADLINE NEWS said. As for Kona Gold, trainer Bruce Headley said, “He was CLASSIC...Albert The Great (Go For Gin), jum ping and squealing when he pulled up. He’s com ing up who will be trying to end a three- race los- to the race perfect.” ing streak when he starts in the Classic, BESSEMER TRUST JUVENILE...The three favorites for Satur- breezed five furlongs in 1:02 over the day’s race recorded solid works yesterday m orning. GI Belm ont m ain track yesterday m orning. Cham pagne S. winner O ffic e r (Bertrando), who loom s the “That was the plan, we didn’t want to go too fast,” said heaviest favorite on the card, stopped trainer Bob Baffert’s trainer Nick Zito. Jockey Jorge Chavez was in the saddle for clock in :59 2/5 for five furlongs at Santa Anita. “He the m ove and w ill be back aboard the Tracy Farm er- ow ned worked great,” the conditioner said of his unbeaten colt. “It four- year- old Saturday. Gary Stevens rode the bay to a was a nice steady five-eighths. I clocked him going out fourth-place finish in the GI Jockey Club Gold Cup Oct. 6. three- quarters in 1:11.74. He was really aggressive and he “Jorge worked him in 1:05 before the Classic last year and didn’t get tired.” John Toffan and Trudy McCaffery’s he ran fourth,” Zito continued. -

Janamsakhi Tradition – an Analytical Study –

Janamsakhi Tradition – An Analytical Study – Janamsakhi Tradition – An Analytical Study – DR. KIRPAL SINGH M.A., Ph.D Edited by Prithipal Singh Kapur Singh Brothers Amritsar JANAMSAKHI TRADITION – AN ANALYTICAL STUDY – by DR KIRPAL SINGH M.A., Ph.D. Former Professor & Head Punjab Historical Studies Deptt. Punjabi University, Patiala ISBN 81-7205-311-8 Firs Edition March 2004 Price : Rs 395-00 Publishers: Singh Brothers Bazar Mai Sewan, Amritsar - 143 006 S.C.O. 223-24, City Centre, Amrisar - 143 001 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.singhbrothers.com Printers : PRINWELL, 146, INDUSTRIAL FOCAL POINT, AMRITSAR Contents – Preface 7 – Introduction 13 1. Genesis of the Janamsakhi Tradition 25 2. Analytical Study of the Janamsakhi Tradition - I 55 3. Analytical Study of the Janamsakhi Tradition - II 204 4. Light Merges with the Divine Light 223 Appendices (i) Glossary of Historical Names in the Janamsakhi 233 (ii) Bibliography 235 – Index 241 6 7 Preface With the Guru’s Grace knowledge is analysed — Guru Nanak (GG 1329) The Janamsakhi literature as such relates exclusively to the life and teachings of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. The spectrum of this genre of literature has several strands. It elucidates mystic concepts of spiritual elevation, provides the earliest exegesis of the hymns of Guru Nanak and illustrates the teachings of Guru Nanak by narrating interesting anecdotes. The most significant aspect of the Janamsakhi literature is that it has preserved the tradition of Guru Nanak’s life that became the primary source of information for all the writings on Guru Nanak. Of late the historical validity of this material has been called to question in the name of methodology. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 4/29/07 • PAGE 2 of 10

CHINESE DRAGON wins off 12-month HEADLINE break...p. 2 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2007 SIMPLY DIVINE THE CAT’S MEOW Stepping up to stakes company for the first time GII Illinois Derby and GIII Gotham S. winner Cowtown yesterday in the GIII Withers S., Divine Park (Chester Cat (Distorted Humor) posted the second-fastest time House) led nearly every step to for yesterday=s five-eighths breeze at maintain his perfect record. AHe Keeneland, covering the distance in stepped his game up a couple of :58.60 (video) while breezing in com- notches,@ said Artie Magnuson, pany with stablemate Magnificent assistant to winning trainer Kiaran Song. After a final quarter in :22 3/5, McLaughlin. AWe=re definitely going the chestnut galloped out in 1:11. in the right direction.@ The bay will AThat=s as good as a horse can work continue his rise up the class lad- right there,@ said trainer Todd Divine Park der, but his next start isn=t yet cer- Pletcher. AHe went very well and fin- Adam Coglianese photo tain. AHe=s a special horse,@ ished up strong.@ Pletcher=s four other Cowtown Cat Magnuson added. AThere=s the Pe- GI Kentucky Derby hopefuls--Any Adam Coglianese photo ter Pan [GII, 9f, BEL, May 20] and the Preakness [GI, Given Saturday (Distorted Humor), $1 million, 1 3/16m, PIM, May 19]. [Owner] Jim [Barry] Circular Quay (Thunder Gulch), Sam P. -

CPIN Pakistan Ahmadis

Country Policy and Information Note Pakistan: Ahmadis Version 4.0 March 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis of COI; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

Al-Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge

Al-Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge Dahlia El-Tayeb M. Gubara Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Dahlia El-Tayeb M. Gubara All rights reserved ABSTRACT Al-Azhar and the Orders of Knowledge Dahlia El-Tayeb M. Gubara Founded by the Fatimids in 970 A.D., al-Azhar has been described variously as “the great mosque of Islam,” “the brilliant one,” “a great seat of learning…whose light was dimmed.” Yet despite its assumed centrality, the illustrious mosque-seminary has elicited little critical study. The existing historiography largely relies on colonial-nationalist teleologies charting a linear narrative of greatness (the ubiquitous ‘Golden Age’), followed by centuries of decline, until the moment of European-inspired modernization in the late nineteenth century. The temporal grid is in turn plotted along a spatial axis, grounded in a strong centrifugal essentialism that reifies culturalist geographies by positioning Cairo (and al-Azhar) at a center around which faithfully revolve concentric peripheries. Setting its focus on the eighteenth century and beyond, this dissertation investigates the discursive postulates that organize the writing of the history of al-Azhar through textual explorations that pivot in space (between Europe and non-Europe) and time (modernity and pre- modernity). It elucidates shifts in the entanglement of disciplines of knowledge with those of ‘the self’ at a particular historical juncture and location, while paying close attention to the act of reading itself: its centrality as a concept and its multiple forms and possibilities as a method. -

EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Artefacts Available for Loan

EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Artefacts available for loan WOLVERHAMPTON LIBRARIES EDUCATION LIBRARY SERVICE Parkfield Centre Wolverhampton Road East Wolverhampton WV4 6AP Tel: 01902 555907 Email: [email protected] OPENING HOURS Monday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 6:00 Tuesday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Wednesday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Thursday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 5:00 Friday 8:30 – 1:00 2:00 – 4:30 The resources detailed in this booklet are available to loan by teachers and other educationalists whose schools have bought in to the Education Library Service Level Agreement. Resources are available to be booked in advance. Please telephone or email any booking requests. 1 Religion Christianity: Easter TK 200 Pt.1 Contents: 1 Crucifix 1 Cross of the risen Christ 1 Paschal Candle 3 Palm crosses 1 Gold Cloth (“Colour for Easter”) 1 Booklet – “Easter and Holy Week” 1 Stations of the Cross booklet 2 Easter cards 3 Posters – The Easter Story, Easter Eggs and An Easter table 1 Hot cross bun – varnished 1 Decorated tin egg (2 parts) 4 Laminated A4 sheets Easter candle + description Palm cross + description 2 Christianity: Christmas TK 200 Pt.2 Contents: 1 Candle 1 Mince Pie (plastic) 1 Mistletoe 1 Holly 1 Nativity Scene 3 Christianity: Christmas TK 200 Pt.3 Contents: 6 Christmas Cards 1 Nativity Crib with Figures and Light 1 White Stole 1 Advent Candle 1 Advent Calendar 1 Fabric for Display Drape 1 Music CD 3 Wise Men – Russian Figures 3 Wise Men in Straw from Czech Republic 1 Icon – Madonna and Child 1 Stained Glass with Christmas Story 1 Book – Christmas Story 1 Christmas Book – Activities for Pupils and Notes for Teachers 4 Christianity: Prayer and Devotion TK 200 Pt.4 Contents: 1 Rosary 1 Thurible 1 Incense Pot 1 Bag of Incense 2 Charcoal Bricks 2 Votive Candles 4 Icons – Madonna and Child Last Supper Our Lord Virgin Mary 1 Bible 1 New Testament and Psalms 1 Book of Common Prayer 1 Lectionary 1 Booklet – “The Baptists” 5 Christianity: Rites of Passage TK 200 Pt.5 Contents: 1. -

Sikh Religion and Islam

Sikh Religion and Islam A Comparative Study G. S. Sidhu M.A. Gurmukh Singh Published by: - © Copyright: G. S. Sidhu and Gurmukh Singh No. of Copies: Year Printer: ii INDEX ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS BOOK ........................................ 1 MAIN ABBREVIATIONS:........................................................................... 1 SOURCES AND QUOTATIONS .................................................................. 1 QUOTATIONS FROM THE HOLY SCRIPTURES ........................................... 2 SIKH SOURCES ..................................................................................... 2 ISLAMIC SOURCES ................................................................................. 2 FOREWORD .................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 1 ..................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 6 1.1 THE NEED FOR RELIGION ........................................................ 6 1.2 THE NEED FOR THIS STUDY ..................................................... 7 1.3 SIKHISM AND ISLAM: INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS ................... 11 CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................... 14 APPROACHES .............................................................................. 14 2.1 SIKHISM ..............................................................................