One Man's Justice: My Life in the Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Jackpot:” the Hang-Up Holding Back the Residual Category of Abuse of Process*

“Jackpot:” the Hang-Up Holding back the Residual Category of Abuse of Process* JEFFERY COUSE ** ABSTRACT The abuse of process doctrine allows courts to stay criminal proceedings where state misconduct compromises trial fairness or causes ongoing prejudice to the integrity of the justice system (the “residual category”). The Supreme Court revisited the residual category in the 2014 case R v Babos. In Babos, the Supreme Court provided a three-stage test for determining whether an abuse of process in the residual category warrants a stay of proceedings. This article critically examines Babos and its progeny. Notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s insistence that the focus of the residual category is societal, all three stages of the test remain disconcertingly preoccupied with the circumstances of the individual accused. Courts’ reluctance to give undeserving accused the “jackpot” remedy of a stay has prevented the court from dissociating itself from state misconduct. Instead, courts have imposed remedies which inappropriately redress wrongs done to the accused. This paper suggests four ways for courts to better advance the societal aim of the residual category. First, a cumulative approach should be taken to multiple instances of state misconduct rather than an individualistic one. Second, courts ought to canvass creative remedies in considering whether an * This paper was written in a personal capacity and does not in any way reflect the views of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice or the Ministry of the Attorney General. ** Jeffery Couse graduated from the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law in 2016 and he was called to the Bar on June 26, 2017. -

Download Download

Generations and the Transformation of Social Movements in Postwar Canada DOMINIQUE CLE´ MENT* Historians, particularly in Canada, have yet to make a significant contribution to the study of contemporary social movements. State funding, ideological conflict, and demographic change had a critical impact on social movements in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, as this case study of the Ligue des droits de l’homme (Montreal) shows. These developments distinguished the first (1930s–1950s) from the second (1960s–1980s) generation of rights associations in Canada. Generational change was especially pronounced within the Ligue. The demographic wave led by the baby boomers and the social, economic, and political contexts of the period had a profound impact on social movements, extending from the first- and second-generation rights associations to the larger context including movements led by women, Aboriginals, gays and lesbians, African Canadians, the New Left, and others. Les historiens, en particulier au Canada, ont peu contribue´ a` ce jour a` l’e´tude des mouvements sociaux contemporains. Le financement par l’E´ tat, les conflits ide´olo- giques et les changements de´mographiques ont eu un impact de´cisif sur les mouve- ments sociaux au Canada lors des anne´es 1960 et 1970, comme le montre la pre´sente e´tude de cas sur la Ligue des droits de l’homme (Montre´al). Ces de´veloppements ont distingue´ les associations de de´fense des droits de la premie`re ge´ne´ration (anne´es 1930 aux anne´es 1950) de ceux de la deuxie`me ge´ne´ration (anne´es 1960 aux anne´es 1980) au Canada. -

Adrian Keane and Paul Mckeown, the Modern Law of Evidence, 12Th Edition Update: September 2019

Adrian Keane and Paul McKeown, The Modern Law of Evidence, 12th Edition Update: September 2019 Chapter 11: Hearsay in criminal cases Cases where a witness is unavailable Page 328 Section 116(1)(a) will also operate to prevent s 116 being used where there is an overwhelming probability that the witness would rely on the privilege against self- incrimination and would decline to give evidence in the terms of the statement. See R v Hayes [2018] 1 Cr App R 134 (10), CA at [58]-[59] Relevant person cannot be found even though such steps as are reasonably practicable to take to find him have been taken Page 330 Where the judge concludes that the requirements of s 116(2)(d) are met, the statement is admissible and it is an error of approach to then consider as the ‘next step’, admissibility under s 114(1)(d). The next step is to consider the question of fairness and the application of s 78 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. See R v Kiziltan [2018] 4 WLR 43, CA at [16]. Business and other documents Section 117 Page 337 Where a statement contained in a document is an opinion, it does not meet the test for admissibility under s 117(1)(a), since oral evidence of opinion is inadmissible (unless it is an expert opinion): R v Hayes [2018] 1 Cr App R 134 (10), CA. Admissibility in the interests of justice Section 114(1)(d): inclusionary discretion Pages 340-341 Where the identity of a witness is not known, it may be possible to use s 114(1)(d) if the witness is untraceable and in the circumstances in which the statement was © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

Volume 13 No. 3

Nikkei Images National Nikkei Museum and Heritage Centre Newsletter ISSN#1203-9017 Fall 2008, Vol. 13, No. 3 The ‘River Garage’ by Theodore T. Hirota My father the foot of Third Hayao Hirota was Avenue it spread born on January e a s t w a r d a w a y 25, 1910, in the from the Canadian small fishing vil- Fishing Company’s lage of Ladner, Gulf of Georgia located on the Cannery and burned left bank of the down the Star, Ste- Fraser River in veston, and Light- British Columbia house Canneries as just a few miles well as the London, from where the Richmond, and Star river empties into Hotels before the the Gulf of Geor- fire was stopped at gia. On the right Number One Road. bank of the lower The walls of the arm of the Fraser The Walker Emporium hardware store catered to Steveston’s fishing Hepworth Block industry in the early 1900s. (Photo courtesy T. Hirota) River and right remained the only at the mouth of Block reputedly were ballast from structure left stand- the river, another fishing village, the early sailing ships and were ing on the entire south side of Steveston, was home to 14 salmon replaced by canned salmon on the Moncton Street. All that was left fishing canneries in 1900. return trip to Britain. along the waterfront after the fire At the time of my father’s When a fire broke out were row upon rows of blackened birth, a substantial hardware store at the Star Cannery’s Chinese pilings. -

The Rule of Law and Judicial Independence: Protecting Core Values in Times of Change

THE RULE OF LAW AND JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE: PROTECTING CORE VALUES IN TIMES OF CHANGE Antonio Lamer' I. Introduction For many, Ivan C. Rand is a name from the past. For me, he is far more than that. When I was called to the Bar of Québec in 1957, Ivan Rand was still a member of the Supreme Court of Canada. The contribution that Ivan Rand made to this country remains significant even after his untimely death in 1969. The Rand formula remains a part of our labour law lexicon. The many thoughtful articles that he contributed to legal journals over the course of his career, as a practitioner, as a judge, and finally as a legal academic, continue to stimulate and to enlighten us. Most importantly the judgments that he wrote, particularly in the area of constitutional law, still provide us with inspiration and guidance as we face the challenges that confront our legal system, particularly those posed by the Charter. In fact, it is a rare decision of the Supreme Court of Canada that deals with one of the fundamental freedoms in the Charter for the first time and does not invoke a passage from one of Justice Rand’s memorable decisions from the 1950s, such as Boucher v. R.,1 Saumur v. Québec (City of),2 or Switzman v. Elbling.3 What makes the decisions of Justice Rand such useful sources of guidance on the interpretation and application of the fundamental freedoms of the Charter is that, unlike most Canadian judges prior to the advent of the Charter, Justice Rand recognized the importance of analyzing issues of constitutional policy in terms of the fundamental or core values of our system of government. -

April 1938 125 Royal Canadian Mounted Police

APRIL 1938 125 ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE HEADQUARTERS OTTAWA. Ont., April 20th, 1938. SECRET NO. 889 WRF.KI .Y SUMMARY RF.PORT ON COMMUNIST AND FASCT.ST ORGANIZATIONS AND AC.ITATION IN CANADA REPORT Tim Buck, fit and increased in weight "through being able to share for a time the good life of the Soviet Union," returned to Toronto on the 18th April and was officially welcomed home at a C.P. mass rally in Massey Hall on the evening of the following day. "Canada welcomes you home, beloved leader," read a slogan emblazoned on a banner which dominated the stage set to suit the occasion. Buck delivered a lengthy address entitled "Europe on the brink of war" in the course of which he charged that through his agreement with Italy, Prime Minister Chamberlain "has completed his systematic betrayal of Spain." APPENDICES TARI F OF CONTENTS APPENDIX NO I-GENERAI. A. Communism. Para. No. 1. C.I.O. to form Federation in opposition to A.E. of L. " " 2. The Communist Party and the Canadian Seamens' Union. " " 3. The campaign in aid of China. Dr. Heng Chih Tao in Western Canada. " " 4. Anti-Padlock Law Conference in Toronto. " " 5. Strikes and Unrest throughout Canada. (i) Taxi Drivers strike at Toronto. (ii) Seamens' Union conducts successful strike. (iii) Relief recipients strike at Calgary. (iv) Edmonton Unemployed stage demonstration. 126 THE DEPRESSION YEARS. PART V B.Easmm. ' 6. Canadian Union of Fascists at Regina urged to concentrate on youth. Attempt to extend National Youth League of Canada. ' 7. Canadian Nationalist Party at Winnipeg shows little activity. -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

The Rise and Decline of the Cooperative Commonwealth

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies B. A. State University of New York at Potsdam, 1987 M. A. State University of New York at Empire State, 2005 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine December 2019 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Nathan Godfried, Professor of History Stephen Miller, Professor of History Howard Cody, Professor Emeritus of Political Science Copyright 2019 Charles A. Deshaies All Rights Reserved ii THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott See and Dr. Jacques Ferland An Abstract of the Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) December 2019 The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was one of the most influential political parties in Canadian history. Without doubt, from a social welfare perspective, the CCF helped build and develop an extensive social welfare system across Canada. It has been justly credited with being one of the major influences over Canadian social welfare policy during the critical years following the Great Depression. This was especially true of the period of the Second World War when the federal Liberal government of Mackenzie King adroitly borrowed CCF policy planks to remove the harsh edges of capitalism and put Canada on the path to a modern Welfare State. -

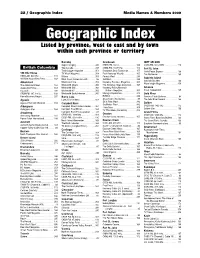

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Benchmark Publication

Friday, 11 November 2016 Weekly Criminal Law Review Editor - Richard Thomas of Counsel A Weekly Bulletin listing Decisions of Superior Courts of Australia covering criminal Search Engine Click here to access our search engine facility to search legal issues, case names, courts and judges. Simply type in a keyword or phrase and all relevant cases that we have reported in Benchmark since its inception in June 2007 will be available with links to each case. Executive Summary The Queen, on the application of Denby Collins v The Secretary of State for Justice (UK - QBD) - criminal law - householder’s defence - householder restrained intruder in headlock who sustained serious injuries - whether householder entitled to rely upon householder’s defence - whether defence limited to ‘reasonable force’ - whether defence incompatible with right to life protection under human rights convention - defence limited to ‘reasonable force’ (WCL) Kelly v R (NSWCCA) - criminal law - sentence appeal - applicant with psychiatric issues and cognitive disorder pleaded guilty to 6 offences, including wounding causing grievous bodily harm (‘GBH’) - applicant represented himself on sentence and failed to adduce relevant, available psychiatric evidence - on appeal, arguing miscarriage because of incompetent representation - appeal allowed, resentenced R v Adams (No 5) (NSWSC) - criminal law - evidence - admissibility of representations contained in historical documents tendered on voir dire - 1983 murder - documents business records of police service - whether hearsay -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University.