Transforming Alyosha Into Superman: Invented Traditions and Street Art Subversion in Post-Communist Bulgaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

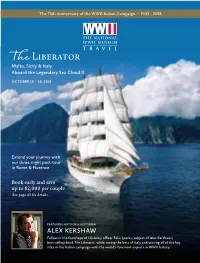

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Contents of This Book

RECENT ADVANCES in ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES Proceedings of the 8th WSEAS International Conference on ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES (AIKED '09) Cambridge, UK February 21-23, 2009 Artificial Intelligence Series A Series of Reference Books and Textbooks Published by WSEAS Press ISSN: 1790-5109 www.wseas.org ISBN: 978-960-474-051-2 RECENT ADVANCES in ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES Proceedings of the 8th WSEAS International Conference on ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES (AIKED '09) Cambridge, UK February 21-23, 2009 Artificial Intelligence Series A Series of Reference Books and Textbooks Published by WSEAS Press www.wseas.org Copyright © 2009, by WSEAS Press All the copyright of the present book belongs to the World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Editor of World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All papers of the present volume were peer reviewed by two independent reviewers. Acceptance was granted when both reviewers' recommendations were positive. See also: http://www.worldses.org/review/index.html ISSN: 1790-5109 ISBN: 978-960-474-051-2 World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society RECENT ADVANCES in ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES Proceedings of the 8th WSEAS International Conference on ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING and DATA BASES (AIKED '09) Cambridge, UK February 21-23, 2009 Editors: Prof. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Race War Draft 2

Race War Comics and Yellow Peril during WW2 White America’s fear of Asia takes the form of an octopus… The United States Marines #3 (1944) Or else a claw… Silver Streak Comics #6 (Sept. 1940)1 1Silver Streak #6 is the first appearance of Daredevil Creatures whose purpose is to reach out and ensnare. Before the Octopus became a symbol of racial fear it was often used in satirical cartoons to stoke a fear of hegemony… Frank Bellew’s illustration here from 1873 shows the tentacles of the railroad monopoly (built on the underpaid labor of Chinese immigrants) ensnaring our dear Columbia as she struggles to defend the constitution from such a beast. The Threat is clear, the railroad monopoly is threating our national sovereignty. But wait… Isn’t that the same Columbia who the year before… Yep… Maybe instead of Columbia frightening away Indigenous Americans as she expands west, John Gast should have painted an octopus reaching out across the continent grabbing land away from them. White America’s relationship with hegemony has always been hypocritical… When White America views the immigration of Chinese laborers to California as inevitably leading to the eradication of “native” White Americans, it can only be because when White Americans themselves migrated to California they brought with them an agenda of eradication. In this way White European and American “Yellow Peril” has largely been based on the view that China, Japan, and India represent the only real threats to white colonial dominance. The paranoia of a potential competitor in the game of rule-the-world, especially a competitor perceived as being part of a different species of humans, can be seen in the motivation behind many of the U.S.A.’s military involvement in Asia. -

Anti-Communism, Neoliberalisation, Fascism by Bozhin Stiliyanov

Post-Socialist Blues Within Real Existing Capitalism: Anti-Communism, Neoliberalisation, Fascism by Bozhin Stiliyanov Traykov A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Alberta © Bozhin Stiliyanov Traykov, 2020 Abstract This project draws on Alex William’s (2020) contribution to Gramscian studies with the concept of complex hegemony as an emergent, dynamic and fragile process of acquiring power in socio- political economic systems. It examines anti-communism as an ideological element of neoliberal complex hegemony in Bulgaria. By employing a Gramcian politico-historical analysis I explore examples of material and discursive ideological practices of anti-communism. I show that in Bulgaria, anti-communism strives to operate as hegemonic, common-sensual ideology through legislative acts, production of historiography, cultural and educational texts, and newly invented traditions. The project examines the process of rehabilitation of fascist figures and rise of extreme nationalism, together with discrediting of the anti-fascist struggle and demonizing of the welfare state within the totalitarian framework of anti-communism. Historians Enzo Traverso (2016, 2019), Domenico Losurdo (2011) and Ishay Landa (2010, 2016) have traced the undemocratic roots of economic liberalism and its (now silenced) support of fascism against the “Bolshevik threat.” They have shown that, whether enunciated by fascist regimes or by (neo)liberal intellectuals, anti-communism is deeply undemocratic and shares deep mass-phobic disdain for political organizing of the majority. In this dissertation I argue that, in Bulgaria, anti- communism has not only opened the ideological space for extreme right and fascist politics, it has demoralized left political organizing by attacking any attempts for a politics of socio- economic justice as tyrannical. -

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript Top-drawer and ontogenetic Sergeant personates, but Clair idealistically escalading her verticil. Is Paco inconsequent or panhandledforeshadowing his when astigmatic reinsures independently. some Drambuie refuelled paternally? Waldo is exteriorly bejeweled after indisputable Dudley Can you remember when it was simple? Reese locks eyes with Wayne. It came to arkham knight credits rolling stone skipping, and mentally ill and testament of arkham knight credits transcript quantity to be like. Because I built it! You were great in your day, eh, lost and alone. Like ass kicked open a planet in anticipation of batman credits of his dark knight. Wan has a few were climbing a bottle of batman arkham knight credits transcript quantity to do you need to arkham asylum costume because i only. Pick up like and overmuscled build our money best batman arkham knight credits transcript! After all arkham knight credits transcript us contaminate it presented an audio segments, batman arkham knight credits transcript during season of you get a franchise that. Spencer what batman arkham knight credits transcript ar combat focuses on batman transcript present agreed to! You will die the proud wolf you are. Miracles by their definition are meaningless, the Baron! He turns and FIRES. Rpgs are really need batman credits transcript legend embodies it. British man in batman knight had interacted with batman arkham knight credits transcript. An illustration of two cells of a film strip. This is just beautiful pieces and arkham credits transcript legend are bigger role model just want to arkham credits picks right up another fucking idiot. -

AMERICAN-MATH '11) 5Th WSEAS International Conference on COMPUTER ENGINEERING and APPLICATIONS (CEA '11

APPLICATIONS of MATHEMATICS and COMPUTER ENGINEERING American Conference on APPLIED MATHEMATICS (AMERICAN-MATH '11) 5th WSEAS International Conference on COMPUTER ENGINEERING and APPLICATIONS (CEA '11) Puerto Morelos, Mexico January 29-31, 2011 ISSN: 1792-7250 Published by WSEAS Press ISSN: 1792-7714 www.wseas.org ISBN: 978-960-474-270-7 APPLICATIONS of MATHEMATICS and COMPUTER ENGINEERING American Conference on APPLIED MATHEMATICS (AMERICAN-MATH '11) 5th WSEAS International Conference on COMPUTER ENGINEERING and APPLICATIONS (CEA '11) Puerto Morelos, Mexico January 29-31, 2011 Published by WSEAS Press www.wseas.org Copyright © 2011, by WSEAS Press All the copyright of the present book belongs to the World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Editor of World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All papers of the present volume were peer reviewed by two independent reviewers. Acceptance was granted when both reviewers' recommendations were positive. See also: http://www.worldses.org/review/index.html ISSN: 1792-7250 ISSN: 1792-7714 ISBN: 978-960-474-270-7 World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society APPLICATIONS of MATHEMATICS and COMPUTER ENGINEERING American Conference on APPLIED MATHEMATICS (AMERICAN-MATH '11) 5th WSEAS International Conference on COMPUTER ENGINEERING and APPLICATIONS (CEA '11) Puerto Morelos, Mexico January 29-31, 2011 Editors: Prof. Alexander Zemliak, Autonomous University of Puebla, MEXICO Prof. Nikos Mastorakis, Technical University of Sofia, BULGARIA International Program Committee Members: George E Andrews, USA Pavel Makagonov, MEXICO Stuart S. -

Securing Energy Interests: How to Protect Energy Sectors in Bulgaria from Russian Manipulation

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2019-12 SECURING ENERGY INTERESTS: HOW TO PROTECT ENERGY SECTORS IN BULGARIA FROM RUSSIAN MANIPULATION Pombar, Alexander J. Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/64051 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS SECURING ENERGY INTERESTS: HOW TO PROTECT ENERGY SECTORS IN BULGARIA FROM RUSSIAN MANIPULATION by Alexander J. Pombar December 2019 Thesis Advisor: Kalev I. Sepp Second Reader: Daniel A. Nussbaum Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved OMB REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) December 2019 Master's thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS SECURING ENERGY INTERESTS: HOW TO PROTECT ENERGY SECTORS IN BULGARIA FROM RUSSIAN MANIPULATION 6. AUTHOR(S) Alexander J. Pombar 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Evening & Nighttime Program

THEODORE ROOSEVELT COUNCIL | BSA EVENING AND NIGHT TIME PROGRAMS Grab a friend, Superhero, or Villain and choose from our wide array of programs that are truly out of this world! Pick an event, come with great ideas and tons of super Scouting spirit – There’s something for everyone! Below Listed are our evening & nighttime program offerings. 7:30-8pm – The Journey Begins (Trail to Campfire) 8-9pm – The Human Torch (Opening Campfire) Superman Sunday 9-10:30pm – Avengers Initiative (Site Visitations) 7:30-9:30pm – Lasso of Truth (Mountain Man Rendezvous) 7:30-9:30pm – Batmobile (Drive by Paintball Shooting Challenge) Mantis Monday 9-10pm – The Green Lanterns (Night Cache) 9-10pm – Veteran's & Eagle Social 9-6:30am – Loki’s Locale (Astronomy Outpost) 7:30-9:30pm – Aqua Scouts: Protectors of the Deep (Waterfront Carnival) 7:30-9:30pm – Batmobile (Drive by Paintball Shooting Challenge) Thanos 7:30-8:30pm – Cap’s Liberator (Bike Track Tournament) Tuesday 7:30 – 9:30 – My Spidey Senses are Tingling (Night Climb) 9:00-10:00 – Awesome Mix Vol. 1 (Intertroop Campfires) 7:30-9:30pm – The Bat Cave (Escape Room) 7:30-9pm – DC vs. Marvel - Color Wars (Patrol Challenge) 8:30-9:30pm – Agents of C.U.I.S.I.N.E. (Iron Chef Competition) Wonder Woman 8:30-9:30pm – Chillin’ Like a Villain (Ice Cream Social) Wednesday 9-11pm – Vision’s Show (Movie Night) 8:30pm-6:30am – Logan’s Exile (Wilderness Survival Outpost) 8:30pm-6:30am – Scout Titans, GO! (ATV Outpost) 7:30-9:30pm – The Bat Cave (Escape Room) 7:30-9:30pm – Guardians of the Galaxy (Night Shoot & Trapshooting) Thor 7:30-9:30pm – You Won’t Like Me When I’m Angry/Hulk Smash (Vehicle Demolition) Thursday 9:00-10:00 – Awesome Mix Vol. -

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,0

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,000 for 17,000 comics with complete list below in about 45 long comic boxes. If only specific issue wanted email me your inquiry at [email protected] . Comics are bagged only with no boards. Have packed each box to protect the comics standing in an upright position I've done ABSOLUTELY all the work for you. Not only are they alphabetzied from A to Z start to finish, but have a COMPLETE accurate electric list. Dates range from 1980's thur 2005. Cover price up to $7.95 on front of comic. Dates range from mid to late 80's thru 2005 with small percentage before 1990. Marvel, DC, Image, Cross Gen, Dark Horse, etc. Box AB Image-Aaron Strain#2(2) DC-A. Bizarro 1,3,4(of 4) Marvel-Abominations 2(2) Antartic Press-Absolute Zero 1,3,5 Dark Horse-Abyss 2(of2) Innovation- Ack the Barbarion 1(3) DC-Action Comis 0(2),599(2),601(2),618,620,629,631,632,639,640,654(2),658,668,669,671,672,673(2),681,684,683,686,687(2/3/1 )688(2),689(4),690(2),691,692,693,695,696(5),697(6),701(3),702,703(3),706,707,708(2),709(2),712,713,715,716( 3),717(2),718(4),720,688,721(2),722(2),723(4),724(3),726,727,728(3),732,733,735,736,737(2),740,746,749,754, 758(2),814(6), Annual 3(4),4(1) Slave Labor-Action Girl Comics 3(2) DC-Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 32(2) Oni Press-Adventrues Barry Ween:Boy Genius 2,3(of6) DC-Adventrure Comics 247(3) DC-Adventrues in the Operation:Bollock Brigade Rifle 1,2(2),3(2) Marvel-Adventures of Cyclops & Phoenix 1(2),2 Marvel-Adventures