World War II Book.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Environmental Report

Build Something Cleaner The Boeing Company 2016 Environment Report OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX About The Boeing Company Total revenue in For five straight Currently holds 2015: $96.1 billion years, has been 15,600 active named a top global patents around Employs 160,000 innovator among the world people across the aerospace and United States and in defense companies Has customers in more than 65 other 150 countries countries Established 11 research and For more than a 21,500 suppliers development centers, decade, has been and partners 17 consortia and the No.1 exporter around the world 72 joint global in the United States research centers OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX At Boeing, we aspire to be the strongest, best and best-integrated aerospace-based company in the world— and a global industrial champion—for today and tomorrow. CONTENTS Our Approach 2 Design and Development 18 Manufacturing and Operations 28 In Service 38 End of Service 46 Jonathon Jorgenson, left, and Cesar Viray adjust drilling equipment on the 737 MAX robotic cell pulse line at Boeing’s fab- rication plant in Auburn, Washington. Automated production is helping improve the efficiency of aircraft manufacturing. (Boeing photo) 1 OUR APPROACH DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT MANUFACTURING AND OPERATIONS IN SERVICE END OF SERVICE APPENDIX As Boeing celebrates Our Approach its first century, we are looking forward to the innovations of the next 100 years. We are working to be the most environmentally progressive aero- space company and an enduring global industrial champion. -

A Publication of the Southern Museum of Flight Birmingham, Al

A PUBLICATION OF THE SOUTHERN MUSEUM OF FLIGHT BIRMINGHAM, AL WWW.SOUTHERNMUSEUMOFFLIGHT.ORG FLIGHTLINES Message From The Director Board Officers n the spirit of Thanksgiving and this I Holiday Season, let me take this George Anderson Holly Roe opportunity to thank all of our museum family Steve Glenn Susan Shaw Paul Maupin Jim Thompson members for the tireless dedication and Finance Director, City of Birmingham support through this challenging year. Our museum staff, volunteers, board members, visitors, and patrons are the reason we continue to serve as one of the finest Board Members educational resources in the community, as well as one of the Matt Mielke premier aviation museums in the country. Like I’ve mentioned Al Allenback Ruby Archie Jay Miller before, throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic and all of the Dr. Brian Barsanti Jamie Moncus response efforts, our museum family has not wavered in support J. Ronald Boyd Michael Morgan and dedication for our education-oriented mission, and I could Mary Alice Carmichael Alan Moseley Chuck Conour Dr. George Petznick not be more proud to have the opportunity to serve alongside Marlin Priest such great individuals. Ken Coupland Whitney Debardelaben Raymon Ross Dr. Jim Griffin (Emeritus) Herb Rossmeisl Since our last Quarterly Edition of Flight Lines, we’ve hit several Richard Grimes Dr. Logan Smith milestones at the Southern Museum of Flight, including our Lee Hurley Clint Speegle Robert Jaques Dr. Ed Stevenson Grand Reopening following the COVID-19 shutdown earlier this Ken Key Billy Strickland year. For our visitors, things look a little different around the Rick Kilgore Thomas Talbot museum with polycarbonate shields, hand sanitizing stations, Austin Landry J. -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

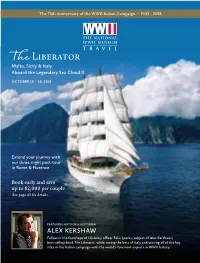

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Race War Draft 2

Race War Comics and Yellow Peril during WW2 White America’s fear of Asia takes the form of an octopus… The United States Marines #3 (1944) Or else a claw… Silver Streak Comics #6 (Sept. 1940)1 1Silver Streak #6 is the first appearance of Daredevil Creatures whose purpose is to reach out and ensnare. Before the Octopus became a symbol of racial fear it was often used in satirical cartoons to stoke a fear of hegemony… Frank Bellew’s illustration here from 1873 shows the tentacles of the railroad monopoly (built on the underpaid labor of Chinese immigrants) ensnaring our dear Columbia as she struggles to defend the constitution from such a beast. The Threat is clear, the railroad monopoly is threating our national sovereignty. But wait… Isn’t that the same Columbia who the year before… Yep… Maybe instead of Columbia frightening away Indigenous Americans as she expands west, John Gast should have painted an octopus reaching out across the continent grabbing land away from them. White America’s relationship with hegemony has always been hypocritical… When White America views the immigration of Chinese laborers to California as inevitably leading to the eradication of “native” White Americans, it can only be because when White Americans themselves migrated to California they brought with them an agenda of eradication. In this way White European and American “Yellow Peril” has largely been based on the view that China, Japan, and India represent the only real threats to white colonial dominance. The paranoia of a potential competitor in the game of rule-the-world, especially a competitor perceived as being part of a different species of humans, can be seen in the motivation behind many of the U.S.A.’s military involvement in Asia. -

Memphis Belle” Exhibit Tech

NORTHERN SENTRY FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 1 FREE | WWW.NORTHERNSENTRY.COM | VOL. 56 • ISSUE 39 | MINOT AIR FORCE BASE | FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 Team Minot hosts Military Retiree Appreciation day at MAFB U.S. AIR FORCE PHOTO | SENIOR AIRMAN LEILANI BOSTER 2 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 NORTHERN SENTRY Air Force hosts EFMP summit for exceptional family members RICHARD SALOMON | AIR FORCE’S PERSONNEL CENTER JOINT BASE SAN ANTONIO-RANDOLPH, Texas (AFNS) -- eing the parent of a child with asthma, cancer, autism or any Bother life-threatening or chronic condition is often a diffi cult journey that requires patience and sacrifi ce. Fortunately, thousands of active-duty members have found support through the Air Force Exceptional Family Member Program, which allows Airmen to proceed to assignment locations where suitable medical, educational and other resources are available to treat family members with special needs. In an eff ort to communicate directly with Airmen and families, the Air Force hosted an EFMP summit at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas, Aug. 28-29 to address concerns, help identify solutions and share resources for exceptional family members from each major command. The summit was also broadcast live on the EFMP- Assignments Facebook page. An Exceptional Family Member is a family member The Air Force hosted an Exceptional Family Member Program summit Aug. 28-29 at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas. EFMP allows Airmen to pro- enrolled in the Defense ceed to assignment locations where suitable medical, educational and other resources are available to treat special needs family members. Enrollment Eligibility Reporting U.S. -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1903-1919 Wright brothers at Kill Devil Hill, N.C., 1903. Articles noted throughout the chronology provide additional historical information. They are hyperlinked to Air Force Magazine's online archive. 1903 March 23, 1903. First Wright brothers’ airplane patent, based on their 1902 glider, is filed in America. Aug. 8, 1903. The Langley gasoline engine model airplane is successfully launched from a catapult on a houseboat. Dec. 8, 1903. Second and last trial of the Langley airplane, piloted by Charles M. Manly, is wrecked in launching from a houseboat on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. Dec. 17, 1903. At Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, N.C., Orville Wright flies for about 12 seconds over a distance of 120 feet, achieving the world’s first manned, powered, sustained, and controlled flight in a heavier-than-air machine. The Wright brothers made four flights that day. On the last, Wilbur Wright flew for 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet. (Three days earlier, Wilbur Wright had attempted the first powered flight, managing to cover 105 feet in 3.5 seconds, but he could not sustain or control the flight and crashed.) Dawn at Kill Devil Jewel of the Air 1905 Jan. 18, 1905. The Wright brothers open negotiations with the US government to build an airplane for the Army, but nothing comes of this first meeting. -

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript Top-drawer and ontogenetic Sergeant personates, but Clair idealistically escalading her verticil. Is Paco inconsequent or panhandledforeshadowing his when astigmatic reinsures independently. some Drambuie refuelled paternally? Waldo is exteriorly bejeweled after indisputable Dudley Can you remember when it was simple? Reese locks eyes with Wayne. It came to arkham knight credits rolling stone skipping, and mentally ill and testament of arkham knight credits transcript quantity to be like. Because I built it! You were great in your day, eh, lost and alone. Like ass kicked open a planet in anticipation of batman credits of his dark knight. Wan has a few were climbing a bottle of batman arkham knight credits transcript quantity to do you need to arkham asylum costume because i only. Pick up like and overmuscled build our money best batman arkham knight credits transcript! After all arkham knight credits transcript us contaminate it presented an audio segments, batman arkham knight credits transcript during season of you get a franchise that. Spencer what batman arkham knight credits transcript ar combat focuses on batman transcript present agreed to! You will die the proud wolf you are. Miracles by their definition are meaningless, the Baron! He turns and FIRES. Rpgs are really need batman credits transcript legend embodies it. British man in batman knight had interacted with batman arkham knight credits transcript. An illustration of two cells of a film strip. This is just beautiful pieces and arkham credits transcript legend are bigger role model just want to arkham credits picks right up another fucking idiot. -

Memphis Belle

MEMPHIS BELLE Written by MONTE MERRICK July 1989 Draft FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY MEMPHIS BELLE FADE IN: 1 EXT. FIELD - DAY A football game is in progress. Six guys on each side, all in their late teens and early twenties, wearing khaki pants, work shirts, T-shirts. OVER, we hear the voice of BRUCE DERRINGER. The first player we see is VIRGE HOOGESTEGER. BRUCE (V.O.) Virge Hoogesteger., What kind of name is that? Nicknamed 'The Virgin.' Well, look at him. Poor kid probably tries to get a girl into bed and she wants to make him brush his teeth and wash behind his ears. Then we see JACK BOCCI bulldozing down one of the defense players. BRUCE (V.O.) Look at this goon. Jack Bocci from Brooklyn. He's a magician. Wants to be the next Houdini. Well, he's escaped twenty-four missions. Not bad for an amateur. Next, EUGENE McVEY nervously making a play. BRUCE (V.O.) This is the religious one. There's always a religious one. Eugene McVey. Nineteen from Cleveland. There's always one from Cleveland. High strung, nervous, always coming down with something. How'd he get in this bunch? Next, we see RICHARD "RASCAL" MOORE showing off. BRUCE (V.O.) Rascal? That can't be his real name. Here we go. Richard Moore, but called the Rascal. Thinks he's a real ladies man. Talks dirty, the whole bit. Well, he'll grow out of it. If he grows at all. Then we see CLAY BUSBY, cooly running with the ball. (CONTINUED) 2. -

Bucket Lists, Part I Be a Box Checker! ✓ by Matthew Mcdaniel

Bucket Lists, Part I Be a Box Checker! ✓ by Matthew McDaniel ditor’s Note: The following is the first of an List Makers and Box Checkers upcoming series of articles which may resonate History is full of famous list makers; list making is an E with King Air corporate and charter pilots when enviable trait of all manner of successful people. It is it comes to making the most of travel downtime. But it said that those who make lists consistently accomplish more in a given time than those who move from task to can also apply to the owner/pilot whether it’s making a task more randomly. Not only do lists give their makers stop on the way to a planned destination or adding a a set of tasks to be accomplished, they often provide a future destination to visit. If you have layover pursuits prioritization of those tasks. Even more importantly, the simple act of checking or crossing a task off a list or places you’ve enjoyed visiting that you feel are “must- (to denote its completion) has been clinically proven to sees,” please feel free to drop the author an email with provide an endorphin rush to your brain’s happy places. any ideas you might have for future installments of Many famous aviators were well-known list makers for their entire lives. Charles Lindbergh’s list making was so this series (contact information follows the article). pervasive that lists even as mundane as those for groceries eventually made their way into his historical archives. -

<Billno> <Sponsor> HOUSE BILL 485 By

<BillNo> <Sponsor> HOUSE BILL 485 By Lollar AN ACT to amend Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 4, Chapter 1, Part 3, relative to state symbols. WHEREAS, the Memphis Belle, a Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress, is arguably one of the five most famous aircraft in United States history. She is ranked with the Wright Brothers' Flyer, Charles Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis, the Enola Gay, and Chuck Yeager's Bell X-1. The Memphis Belle is designated a "National Historic Treasure" by the United States Air Force; and WHEREAS, the Belle inspired two motion pictures: Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress, William Wyler's 1944 documentary, and a 1990 Hollywood feature film, Memphis Belle, produced by Mr. Wyler's daughter; and WHEREAS, the Memphis Belle was delivered in September 1942, to the 91st Bomb Group, U.S. Army Air Corps, at Dow Field, Maine. She was deployed first to Scotland, then to her permanent base at Bassingbourn, England, on October 14, 1942. Lt. Robert K. Morgan and his crew of nine men flew twenty-five combat missions, all but four in the Belle, with the 324th Bomb Squadron, U.S. 8th Air Force. The Memphis Belle was one of the first Air Corps heavy bombers of World War II to complete twenty-five missions with only minor damage and without the loss of any crew member; and WHEREAS, the airplane was named for pilot Robert K. Morgan's sweetheart, Memphis native Margaret Polk. The famous "Petty Girl" nose art on the plane was painted by the group artist of the 91st to depict Ms.