The Representation of Indigenous Languages of Oceania in Academic Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Approved in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic June 14, 2016 During the Forty-sixth Ordinary Period of Sessions of the OAS General Assembly AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES Organization of American States General Secretariat Secretariat of Access to Rights and Equity Department of Social Inclusion 1889 F Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 | USA 1 (202) 370 5000 www.oas.org ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 More rights for more people OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Organization of American States. General Assembly. Regular Session. (46th : 2016 : Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) : (Adopted at the thirds plenary session, held on June 15, 2016). p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.P) ; (OAS. Official records ; OEA/ Ser.D) ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 1. American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2016). 2. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--America. 3. Indigenous peoples--Legal status, laws, etc.--America. I. Organization of American States. Secretariat for Access to Rights and Equity. Department of Social Inclusion. II. Title. III. Series. OEA/Ser.P AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) OEA/Ser.D/XXVI.19 AG/RES. 2888 (XLVI-O/16) AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES (Adopted at the third plenary session, held on June 15, 2016) THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, RECALLING the contents of resolution AG/RES. 2867 (XLIV-O/14), “Draft American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” as well as all previous resolutions on this issue; RECALLING ALSO the declaration “Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas” [AG/DEC. -

Concept Note and Agenda REGIONAL MEETING on ETHNICITY and HEALTH in the AMERICAS 7-8 December 2015 Introduction Available Data

Concept note and agenda REGIONAL MEETING ON ETHNICITY AND HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS 7-8 December 2015 Introduction Available data indicates that indigenous and afrodescent peoples are amongst the most marginalized populations of the region, encountering considerable challenges with regards to social and health conditions and with higher levels of rurality or urban marginality, unemployment, poverty, and illiteracy. They have less access to, and lower utilization of, health services, particularly quality health services, as compared to the rest of the population. Therefore, their health outcomes are poorer, presenting greater morbidity and mortality both from communicable and chronic diseases as well as external causes. Since 1993, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) approved significant Resolutions to address these challenges and to advance the work on ethnicity and health in the region. In 1993, Member States reached consensus in recognizing the deficits in both living conditions and health among the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Resolution 1 aimed to implement the SAPIA initiative (Health of the Indigenous Peoples Initiative of the Americas) and was reinforced by other two Resolutions on indigenous peoples approved in 1997 and 2006 2. The Strategy for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage, approved in 2014, specifically refers to indigenous and afro-descendant as some of the most affected groups facing problems of exclusion and lack of access to appropriate quality services. In addition, at global levels, there has been increasing attention to indigenous and afrodescent issues: the World Conference on Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) was held at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2014. -

The Straits of Magellan Were the Final Piece in in Paris

Capítulo 1 A PASSAGE TO THE WORLD The Strait of Magellan during the Age of its Discovery Mauricio ONETTO PAVEZ 2 3 Mauricio Onetto Paves graduated in 2020 will be the 500th anniversary of the expedition led by history from the Pontifical Catholic Ferdinand Magellan that traversed the sea passage that now carries his University of Chile. He obtained name. It was an adventure that became part of the first circumnavigation his Masters and PhD in History and of the world. Civilizations from the L’École des Ever since, the way we think about and see the world – and even the Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales universe – has changed. The Straits of Magellan were the final piece in in Paris. a puzzle that was yet to be completed, and whose resolution enabled a He is the director of the international series of global processes to evolve, such as the movement of people, academic network GEOPAM the establishment of commercial routes, and the modernization of (Geopolítica Americana de los siglos science, among other things. This book offers a new perspective XVI-XVII), which focuses on the for the anniversary by means of an updated review of the key event, geopolitics of the Americas between based on original scientific research into some of the consequences of the 16th and 17th centuries. His negotiating the Straits for the first time. The focus is to concentrate research is funded by Chile’s National on the geopolitical impact, taking into consideration the diverse scales Fund for Scientific and Technological involved: namely the global scale of the world, the continental scale Development (FONDECYT), and he of the Americas, and the local context of Chile. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

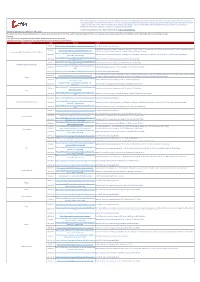

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

1 12Th Oecd-Japan Seminar: “Globalisation And

12TH OECD-JAPAN SEMINAR: “GLOBALISATION AND LINGUISTIC COMPETENCIES: RESPONDING TO DIVERSITY IN LANGUAGE ENVIRONMENTS” COUNTRY NOTE: AUSTRALIA LINGUISTIC CHALLENGES FOR MINORITIES AND MIGRANTS Australia is today a culturally diverse country with people from all over the world speaking hundreds of different languages. Australia has a broad policy of social inclusion, seeking to ensure that all Australians, regardless of their diverse backgrounds are fully included in and able to contribute to society. With its long history of receiving new visitors from overseas, and particularly with the explosion of immigration following World War II, Australia has a great deal of experience in dealing with the linguistic challenges of migrants and minorities. Instead of simply seeking to assimilate new arrivals, Australia seeks to integrate those people into society so that they are able to take full advantage of opportunities, but in a way that respects their cultural traditions and indeed values their diverse experiences. Snapshot of Australian immigration Australia's current Immigration Program allows people from any country to apply to visit or settle in Australia. Decisions are made on a non-discriminatory basis without regard to the applicant's ethnicity, culture, religion or language, provided that they meet the criteria set out in law. In 2005–06, there were 131 600 (ABS, 2006) people who settled permanently in Australia. The top ten countries of origin are: Country of birth % 1 United Kingdom 17.7 2 New Zealand 14.5 3 India 8.6 4 China (excluded SARs and Taiwan) 8.0 5 Philippines 3.7 6 South Africa 3.0 7 Sudan 2.9 8 Malaysia 2.3 9 Singapore 2.0 10 Viet Nam 2.0 Other 35.3 Total 100.0 1 According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2006 census data: Australia's immigrants come from 185 different countries Australians identify with some 250 ancestries and practise a range of religions. -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

OUTLINE Vii PL1-8844 Languages of Eastern Asia, Africa, Oceania PL1-481 Ural-Altaic Languages PL21-396 Turkic Languages PL400-43

OUTLINE PL1-8844 Languages of Eastern Asia, Africa, Oceania PL1-481 Ural-Altaic languages PL21-396 Turkic languages PL400-431 Mongolian languages PL450-481 Tungus Manchu languages PL491-494 Far Eastern languages and literature PL495 Ainu PL501-889 Japanese language and literature PL501-699 Japanese language PL700-889 Japanese literature PL700-751.5 History and criticism PL752-783 Collections PL784-866 Individual authors and works PL885-889 Local literature PL901-998 Korean language and literature PL901-946 Korean language PL950-998 Korean literature PL950.2-969.5 History and criticism PL969.8-985 Collections PL986-994.98 Individual authors and works PL997-998 Local literature PL1001-3208 Chinese language and literature PL1001-1960 Chinese language PL2250-3208 Chinese literature PL2250-2443 History and criticism PL2450-2659 Collections PL2661-2979 Individual authors and works PL3030-3208 Provincial, local, colonial, etc. PL3301-3311 Non-Chinese languages of China PL3501-3509.5 Non-Aryan languages of India and Southeastern Asia in general PL3512 Malaysian literature PL3515 Singapore literature PL3518 Languages of the Montagnards PL3521-4001 Sino-Tibetan languages PL3551-4001 Tibeto-Burman languages PL3561-3801 Tibeto-Himalayan languages PL3601-3775 Tibetan PL3781-3801 Himalayan languages PL3851-4001 Assam and Burma PL4051-4054 Karen languages PL4070-4074 Miao-Yao languages PL4111-4251 Tai languages PL4281-4587 Austroasiatic languages PL4301-4470 Mon-Khmer (Mon-Anam) languages PL4321-4329 Khmer (Cambodian) vii OUTLINE Languages of Eastern -

Considerations for Non-Dominant Language Education in the Global South

FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education Vol. 5, Iss. 3, 2019, pp. 12-28 LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICIES AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION EFFORTS IN CANADA: CONSIDERATIONS FOR NON-DOMINANT LANGUAGE EDUCATION IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Onowa McIvor1 University of Victoria, Canada Jessica Ball University of Victoria, Canada Abstract Indigenous languages are struggling for breath in the Global North. In Canada, Indigenous language medium schools and early childhood programs remain independent and marginalized. Despite government commitments, there is little support for Indigenous language-in-education policy and initiatives. This article describes an inaugural, country- wide, federally-funded, Indigenous-led language revitalization research project, entitled NE OL EW̱ (one mind-one people). The project brings together nine Indigenous partners to build a country-wide network and momentum to pressure multi-levels of government to honourȾ agreementsṈ enshrining the right of children to learn their Indigenous language. The project is documenting approaches to create new Indigenous language speakers, focusing on adult language learners able to keep the language vibrant and teach their language to children. The article reflects upon how this Northern emphasis on Indigenous language revitalization and country-wide networking initiative is relevant to mother tongue-based education and policy examples in the Global South. The article underscores the need for both community level initiatives (top-down) and government level policy and funding (bottom up) to support child and adult Indigenous language learning. Keywords: Indigenous language practices, language-in-education policies, policy reform, First Nations, Indigenous, Canada, Global North, Global South 1 Correspondence: Dr. Onowa McIvor, C/O Dept. of Indigenous Education, University of Victoria, PO Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria BC V8W 2Y2; Email: [email protected] O. -

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia

Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Putra, Kristian Adi Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 19:51:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/630210 YOUTH, TECHNOLOGY AND INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION IN INDONESIA by Kristian Adi Putra ______________________________ Copyright © Kristian Adi Putra 2018 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kristian Adi Putra, titled Youth, Technology and Indigenous Language Revitalization in Indonesia and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -~- ------+-----,T,___~-- ~__ _________ Date: (4 / 30/2018) Leisy T Wyman - -~---~· ~S:;;;,#--,'-L-~~--~- -------Date: (4/30/2018) 7 Jonath:2:inhardt ---12Mij-~-'-+--~4---IF-'~~~~~"____________ Date: (4 / 30 I 2018) Perry Gilmore Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate' s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021 This bulletin is compiled to give all stakeholders an overview of the current impact of COVID-19 on Pacific shipping activities. It draws on sources from government, commercial and humanitarian sectors. The bulletin will now be circulated monthly. Overview • UN Bodies call for seafarers and aviation workers to be given priority access to vaccines • Massive congestion in European and Asian ports anticipated due to resolved Suez Canal blockage State / Territory Date Source Details 26-Mar-21 https://info.swireshipping.com/shipping-schedules/oceania See link for Swire Shipping schedule. Kaimana Hila arrives on 4 March. Maunawili arrives on 11 March. Daniel K. Inouye arrives on 18 March. Manukai arrives 25 March. Maunawili departs 25-Feb-21 https://www.matson.com/fss/reports/guam_s.pdf Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands on 9 March. Daniel K. Inouye departs on 14 March. Manukai departs 21 March. https://www.pdl123.co.nz/common/downloads/images/sch 24-Feb-21 Neptune Pacific has vessels arriving on 7 & 21 March, 10 & 21 April, 5 & 24 May, 4 & 18 June, 7 & 18 July, 20 & 31 August and 14 September. -

Palauea, Honua'ula, Maui

OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS RESEARCH DIVISION Palauea Palauea, Honua‘ula, Maui By Holly K. Coleman Palauea is the name of an ahupua‘a (land division) in the moku (district) of Honua‘ula on the island of Maui. Many believe that Palauea and surrounding areas were focal points and ceremonial centers of the fishing communities of Honua‘ula (Six, 2013). Today, a high concentration of archaeological and cultural sites can be found in the Pa- lauea Cultural Preserve, which is one of the few undevel- oped land parcels in an area surrounded by luxury resi- dences and resorts. At least fourteen native plant species, including what is believed to be the largest natural stand of maiapilo (Capparis sandwichiana), and at least thirteen archaeological complexes have been identified within the preserve area (Donham, 2007). In April 2013, the Dowling Corporation formally con- veyed the Palauea Cultural Preserve to the Office of Ha- waiian Affairs (OHA). Palauea remains a vital cultural and historical resource for Native Hawaiians and the broader community. The goal of this Information Sheet is to explore some of the cultural and historical narratives of Palauea and the surrounding areas, particularly as OHA transitions into the role of care- taker of this place. This Information Sheet will also strengthen the agency’s foundation of knowledge for this wahi pana (storied, legendary place). Left: View of Molokini and Kaho‘olawe from Palauea Heiau. Source: Shane Tegarden Photography for OHA, 2013. Research Division Land, Culture, and History Section Information Sheet, October 2013 Office of Hawaiian Affairs 560 N. Nimitz Hwy, Suite 200, Honolulu, HI 96817 www.oha.org 1 OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS RESEARCH DIVISION Traditional Land Divisions Winds and Rains of Honua‘ula Honua‘ula was known as a dry land; indeed, Honua‘ula means “red land or earth” and may have also been the named for a variety of sweet potato grown in the area as a staple food (Pukui & Elbert, 1974).