Vestiges of Upland Fields in Central Veracruz: a New Perspective on Its Precolumbian Human Ecology Andrew Sluyter Louisiana State University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Structures and Early Life History of the Gulf Toadfish, Opsanus Beta, in the Tecolutla Estuary, Veracruz, Mexico

Gulf and Caribbean Research Volume 16 Issue 1 January 2004 Reproductive Structures and Early Life History of the Gulf Toadfish, Opsanus beta, in the Tecolutla Estuary, Veracruz, Mexico Alfredo Gallardo-Torres Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Jose Antonio Martinez-Perez Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico Brian J. Lezina University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo-Torres, A., J. A. Martinez-Perez and B. J. Lezina. 2004. Reproductive Structures and Early Life History of the Gulf Toadfish, Opsanus beta, in the Tecolutla Estuary, Veracruz, Mexico. Gulf and Caribbean Research 16 (1): 109-113. Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/gcr/vol16/iss1/18 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18785/gcr.1601.18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf and Caribbean Research by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gulf and Caribbean Research Vol 16, 109–113, 2004 Manuscript received September 25, 2003; accepted December 15, 2003 REPRODUCTIVE STRUCTURES AND EARLY LIFE HISTORY OF THE GULF TOADFISH, OPSANUS BETA, IN THE TECOLUTLA ESTUARY, VERACRUZ, MEXICO Alfredo Gallardo-Torres, José Antonio Martinez-Perez and Brian J. Lezina1 Laboratory de Zoologia, University Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Av. De los Barrios No 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, Mexico C.P. 54090 A.P. Mexico 1Department of Coastal Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, 703 E. -

Hurricane Grace Leaves at Least 8 Dead in Mexico 21 August 2021, by Ignacio Carvajal

Hurricane Grace leaves at least 8 dead in Mexico 21 August 2021, by Ignacio Carvajal turned into muddy brown rivers. Many homes in the region were left without electricity after winds that clocked 125 miles (200 kilometers) per hour. "Unfortunately, we have seven deaths" in Xalapa and one more in the city of Poza Rica, including minors, Veracruz Governor Cuitlahuac Garcia told a news conference. Flooding was also reported in parts of neighboring Tamaulipas state, while in Puebla in central Mexico trees were toppled and buildings suffered minor damage. Grace weakened to a tropical storm as it churned A man walks in a flooded street due to heavy rains inland, clocking maximum sustained winds of 45 caused by Hurricane Grace in Tecolutla in eastern miles per hour, according to the US National Mexico. Hurricane Center (NHC). At 1800 GMT, the storm was located 35 miles northwest of Mexico City, which was drenched by Hurricane Grace left at least eight people dead as heavy rain, and moving west at 13 mph, forecasters it tore through eastern Mexico Saturday, causing said. flooding, power blackouts and damage to homes before gradually losing strength over mountains. The storm made landfall in Mexico for a second time during the night near Tecolutla in Veracruz state as a major Category Three storm, triggering warnings of mudslides and significant floods. The streets of Tecolutla, home to about 24,000 people, were littered with fallen trees, signs and roof panels. Esteban Dominguez's beachside restaurant was reduced to rubble. "It was many years' effort," he said. The storm toppled trees and damaged homes. -

Propuesta De Programa De Adaptación Ante El Cambio Climático Para El Destino Turístico De Costa Esmeralda, Veracruz

Academia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo A.C. “Anidando el futuro, hoy” ESTUDIO DE VULNERABILIDAD AL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO EN DIEZ DESTINOS TURÍSTICOS SELECCIONADOS PROYECTO Clave 238980 FONDO SECTORIAL CONACYT- SECTUR Responsable Técnico: Dra. Andrea Bolongaro Crevenna Recaséns PROPUESTA DE PROGRAMA DE ADAPTACIÓN ANTE EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO PARA EL DESTINO TURÍSTICO DE COSTA ESMERALDA, VERACRUZ (Nautla, San Rafael, Tecolutla y Vega de Alatorre) Julio 2016. REGISTROS Y CERTIFICACIONES: Av. Palmira No.13, Col. Miguel Hidalgo, Cuernavaca, Morelos, C.P. 62040, México CONACYT (RENIECYT): 2015/718 Tels/Fax: (01-777) 3145289 y 3105157, Mail: [email protected], ISO 9001:2008 DNV-GL Atención de quejas y/o sugerencias: 01800 506 8783 www.anide.edu.mx 1 Academia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo A.C. “Anidando el futuro, hoy” Responsable Técnico y Coordinador del Proyecto: Dra. Andrea Bolongaro Crevenna Recaséns Colaboradores: Vulnerabilidad Física: Vulnerabilidad Social: Dr. Antonio Z. Márquez García M. en C. Magdalena Ivonne Márquez García M. I. Vicente Torres Rodríguez Dra. Andrea Bolongaro Crevenna Recaséns Dr. Javier Aldeco Ramírez Dra. Marisol Anglés Hernández Dr. Miguel Ángel Díaz Flores Lic. Susana Córdova Novion M. en G. Erik Márquez García Biol. César Caballero Novara M. en B. Laura María Fernández Bringas Pas. Rebeca Moreno Coca Ing. Leonid Ignacio Márquez García Pas. Daniel Cuenca Osuna M en C. María Alejandrina Leticia Montes León Pas. Ing. Elba Adriana Pérez Vulnerabilidad Institucional: Pas. Ing. Emma Verónica Pérez Flores Dra. Marisol Anglés Hernández Pas. Hidrobiol. Belén Eunice García Díaz Dra. Andrea Bolongaro Crevenna Recaséns M. en C. Magdalena Ivonne Márquez García Escenarios de Cambio Climático: Lic. -

Water As More Than Commons Or Commodity: Understanding Water Management Practices in Yanque, Peru

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 12 | Issue 2 Brandshaug, M.K. 2019. Water as more than commons or commodity: Understanding water management practices in Yanque, Peru. Water Alternatives 12(2): 538-553 Water as More than Commons or Commodity: Understanding Water Management Practices in Yanque, Peru Malene K. Brandshaug Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Global warming, shrinking glaciers and water scarcity pose challenges to the governance of fresh water in Peru. On the one hand, Peruʼs water management regime and its legal framework allow for increased private involvement in water management, commercialisation and, ultimately, commodification of water. On the other hand, the state and its 2009 Water Resource Law emphasise that water is public property and a common good for its citizens. This article explores how this seeming paradox in Peruʼs water politics unfolds in the district of Yanque in the southern Peruvian Andes. Further, it seeks to challenge a commons/commodity binary found in water management debates and to move beyond the underlying hegemonic view of water as a resource. Through analysing state-initiated practices and practices of a more-than-human commoning – that is, practices not grounded in a human/nature divide, where water and other non-humans participate as sentient persons – the article argues that in Yanque many versions of water emerge through the heterogeneous practices that are entangled in water management. KEYWORDS: Water, water management, commodification, more-than-human commoning, uncommons, Andes, Peru INTRODUCTION At a community meeting in 2016, in the farming district of Yanque in the southern Peruvian Andes, the water users discussed their struggles with water access for their crops. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4. -

Download Download

LUIS ALFONSO CASTILLO-HERNÁNDEZ AND HILDA FLORES-OLVERA* Botanical Sciences 95 (3): 1-25, 2017 Abstract Background: The Bicentenario Reserve (BR) located in Sierra de Zongolica, Veracruz, includes 63 hect- DOI: 10.17129/botsci.1223 ares of cloud forest (cf) which lacks of systematic foristic studies, but the Sierra proposed as an area for bird conservation. Copyright: © 2017 Castillo-Her- Questions: i) Is the foristic composition of the BR taxonomical rich? ii) How the growth forms are repre- nández & Flores-Olvera. This is an open access article distributed under sented in this Reserve ? iii) Has the BR endemic or threatened species? the terms of the Creative Commons Studied species: Vascular plants. Attribution License, which permits Study site and years of study: The BR was explored from March 2011 to October 2012. unrestricted use, distribution, and Methods: Botanical samples from each species considered different were collected and processed accord- reproduction in any medium, provi- ded the original author and source are ing to conventional procedures to be identifed with the use of taxonomic tools, and consults with special- credited. ist. Analysis of the richness, life forms, endemism and threatened species were made. Results: We recorded 401 species, distributed in 272 genera and 102 families, being the most diverse Orchidaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Piperaceae; whilst Peperomia, Tillandsia, Polypodium, Quercus and Solanum are the genera with the highest number of species. Sixty-nine species are endemic to Mexico, but six are restricted to Veracruz. We found 23 new records for the municipality of Zongolica, Quercus ghiesbreghtii in the cf for the frst time, and Q. -

Water Footprint Assessment of Bananas Produced by Small Banana Farmers in Peru and Ecuador

Water footprint assessment of bananas produced by small banana farmers in Peru and Ecuador L. Clercx1, E. Zarate Torres2 and J.D. Kuiper3 1Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment (TASTE Foundation), Koopliedenweg 10, 2991 LN Barendrecht, The Netherlands; 2Good Stuff International CH, Blankweg 16, 3072 Ostermundigen, Bern, Switzerland; 3Good Stuff International B.V., PO Box 1931, 5200 BX, s’-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands. Abstract In 2013, Good Stuff International (GSI) carried out a Water Footprint Assessment for the banana importer Agrofair and its foundation TASTE (Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment) of banana production by small farmers in Peru and Ecuador, using the methodology of the Water Footprint Network (WFN). The objective was to investigate if the Water Footprint Assessment (WFA) can help define strategies to increase the sustainability of the water consumption of banana production and processing of smallholder banana producers in Peru and Ecuador. The average water footprint was 576 m3 t-1 in Ecuador and 599 m3 t-1 for Peru. This corresponds respectively to 11.0 and 11.4 m3 per standard 18.14 kg banana box. In both samples, approximately 1% of the blue water footprint corresponds to the washing, processing and packaging stage. The blue water footprint was 34 and 94% of the total, respectively for Ecuador and Peru. This shows a strong dependency on irrigation in Peru. The sustainability of the water footprint is questionable in both countries but especially in Peru. Paradoxically, the predominant irrigation practices in Peru imply a waste of water in a context of severe water scarcity. The key water footprint reduction strategy proposed was better and more frequent dosing of irrigation water. -

CLAVE ENTIDAD ENTIDAD CLAVE MUNICIPAL MUNICIPIO Municipio

CLAVE ENTIDAD ENTIDAD CLAVE MUNICIPAL MUNICIPIO Municipio Fommur 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1001 AGUASCALIENTES 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1002 ASIENTOS 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1003 CALVILLO 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1004 COSIO 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1010 EL LLANO 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1005 JESUS MARIA 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1006 PABELLON DE ARTEAGA 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1007 RINCON DE ROMOS 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1011 SAN FRANCISCO DE LOS ROMO 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1008 SAN JOSE DE GRACIA 1 01 AGUASCALIENTES 1009 TEPEZALA 1 02 BAJA CALIFORNIA 2001 ENSENADA 1 02 BAJA CALIFORNIA 2002 MEXICALI 1 02 BAJA CALIFORNIA 2003 TECATE 1 02 BAJA CALIFORNIA 2004 TIJUANA 1 04 CAMPECHE 4010 CALAKMUL 1 04 CAMPECHE 4001 CALKINI 1 04 CAMPECHE 4002 CAMPECHE 1 04 CAMPECHE 4011 CANDELARIA 1 04 CAMPECHE 4003 CARMEN 1 04 CAMPECHE 4004 CHAMPOTON 1 04 CAMPECHE 4005 HECELCHAKAN 1 04 CAMPECHE 4006 HOPELCHEN 1 04 CAMPECHE 4007 PALIZADA 1 04 CAMPECHE 4008 TENABO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7001 ACACOYAGUA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7002 ACALA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7003 ACAPETAHUA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7004 ALTAMIRANO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7005 AMATAN 1 07 CHIAPAS 7006 AMATENANGO DE LA FRONTERA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7009 ARRIAGA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7011 BELLA VISTA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7012 BERRIOZABAL 1 07 CHIAPAS 7013 BOCHIL 1 07 CHIAPAS 7015 CACAHOATAN 1 07 CHIAPAS 7016 CATAZAJA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7022 CHALCHIHUITAN 1 07 CHIAPAS 7023 CHAMULA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7025 CHAPULTENANGO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7026 CHENALHO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7027 CHIAPA DE CORZO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7028 CHIAPILLA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7029 CHICOASEN 1 07 CHIAPAS 7030 CHICOMUSELO 1 07 CHIAPAS 7031 CHILON 1 07 CHIAPAS 7017 CINTALAPA 1 07 CHIAPAS 7018 -

Rethinking the Conquest : an Exploration of the Similarities Between Pre-Contact Spanish and Mexica Society, Culture, and Royalty

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2015 Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2015 Samantha Billing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Billing, Samantha, "Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty" (2015). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 155. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/155 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by SAMANTHA BILLING 2015 All Rights Reserved RETHINKING THE CONQUEST: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN PRE‐CONTACT SPANISH AND MEXICA SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND ROYALTY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa May 2015 ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest has been historically marked by the year 1521 and is popularly thought of as an absolute and complete process of indigenous subjugation in the New World. Alongside this idea comes the widespread narrative that describes a barbaric, uncivilized group of indigenous people being conquered and subjugated by a more sophisticated and superior group of Europeans. -

Tecolutla: Mexico's Gulf Coast Acapulco? Klaus J

Tecolutla: Mexico's Gulf Coast Acapulco? Klaus J. Meyer-Arendt Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, Volume 80, 2018, pp. 97-111 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/pcg.2018.0005 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/702704 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] Tecolutla: Mexico’s Gulf Coast Acapulco? Klaus J. Meyer-Arendt University of West Florida ABSTRACT Tecolutla is a small beach resort along the Gulf of Mexico in Veracruz state, Mexico. At one time a small fishing outpost, it developed into a beach resort in the 1940s as a result of the popularization of sunbathing and infrastructural development facilitated by two Mexican presidents. As the closest beach to Mexico City, Tecolutla briefly rivaled Acapulco as the most popular beach destination in the country. But Tecolutla slowly lost out to its Pacific Coast rival, which had better weather, better access (after 1956), political favoritism (mostly by Miguel Alemán Valdés, na- tive Veracruzano and president of Mexico 1946–1952), and international cachet in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Although Tecolutla never became the envisioned “Gulf Coast Acapulco,” it has steadily grown over the years thanks to better highway access, diversification of attractions, and lower prices. There are still obstacles that prevent it from evolving beyond its current status as a domestic destination resort. Keywords: Tecolutla, seaside resort, tourism development, Mexico Introduction If one were asked to name the top beach resorts in Mexico, perhaps the names Cancun, Acapulco, Puerto Vallarta, Cabo San Lucas (Los Cabos), Puerto Escondido, Ixtapa/Zihuantenejo, Manzanillo, Huatulco, Cozumel, Mazatlán, or even San Felipe would come to mind. -

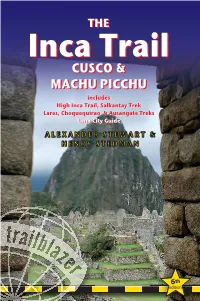

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels, -

The Chronological Period Is a Temporal Unito There Is a Wealth of Material on Late Pre-Columbian Middle America Available Sin the Chronicles and Codices

THE POSTCLASSIC STAGE IN MESOAMERICA Jane Holden INTRODUCTION The subject of inquiry in this paper is the PostcLassic stage in Middle America. As used by prehistorians, the term "Postclassic" has referred to either a developmental stage or to a chronological period. These two con- cepts are quite different, both operationally and theoretically. The stage concept in contemporary usage is a classificatory device for st,udying cul- ture units in terms of developmental and theoretical problems. For com- parative purposes, a stage is usually defined in broad and diffuse terms, in order to outline a culture type. A developmental stage is not tempor- c3lyl detined although it is necessarily a function of relative time. The chronological period on the other hand is defined through the temporal alignment of culture units and establishes the historical contemporaneity of those units. Thus the developmental stage is a typological device and the chronological period is a temporal unito There is a wealth of material on late pre-Columbian Middle America available sin the chronicles and codices. However, the study of such mater- ials. is a ppecialty in itself, hence only a minimum of historical informa- tion *ill be presented in this paper and this will be of necessity, based on secondary sources. The following procedure will be employed in this paper. First, brief summaries of formal statements by various authors on the developmental stage concept will be presented, as well as some temporal classifications of the Postclassic. Secondly, the available archaeological evidence will be summarized to provide a temporal framework. And finally, consideration will be given to the implications derived from the comparison of the Post- classic as a temporal category and as a developmental stage.