Water As More Than Commons Or Commodity: Understanding Water Management Practices in Yanque, Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Privatization in Developing Countries: Principles, Implementations and Socio-Economic Consequences

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 10 (2015) 17-31 EISSN 2392-2192 Water privatization in developing countries: Principles, implementations and socio-economic consequences Sayan Bhattacharya1,*, Ayantika Banerjee2 1Department of Environmental Studies, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata, India 2Department of Environmental science, Asutosh College, Kolkata, India *E-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Water related problems are continuously affecting the social infrastructures and jeopardizing the productivity of modern globalized society. As the water crisis intensifies, several governments around the world are advocating a radical solution: the privatization, commoditization and mass diversion of water. Water privatization involves transferring of water resources control and/or water management services to private companies. The water management service may include operation and management, bill collection, treatment, distribution of water and waste water treatment in a community. The privatization of water has already happened in several developed countries and is being pushed in many developing countries through structural adjustment policies. Water privatization will invariably increase the price of this common property resource because there are hidden costs involved in water collection, purification and distribution systems. Increase in water consumption will be satisfied through the market dynamics often at the cost of the poor who cannot afford the increased water tariffs. The corporations will recover their costs by exploiting the consumers irrespective of their economic conditions. Another possible threat of water privatization is the unsustainable water extraction by the water corporations for maximizing profits and subsequent destructions of water bodies and aquifers. Corporations in search of profits can compromise on water quality in order to reduce costs. -

Distinction Between Privatization of Services and Commodification of Goods: the Case of the Water Supply in Porto Alegre Rafael Flores

Distinction between privatization of services and commodification of goods: the case of the water supply in Porto Alegre Rafael Flores To cite this version: Rafael Flores. Distinction between privatization of services and commodification of goods: the case of the water supply in Porto Alegre. 11th edition of the World Wide Workshop for Young Environmental Scientists (WWW-YES-2011) - Urban Waters: resource or risks?, Jun 2011, Arcueil, France. hal- 00607834 HAL Id: hal-00607834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00607834 Submitted on 11 Jul 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distinction between privatization of services and commodification of goods: the case of the water supply in Porto Alegre Rafael Kruter FLORES* * Postgraduate Program of Administration, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Washington Luís, 855, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract One of the main debates regarding urban water in the last years concerns the privatization of water and sewage services. The critique of the privatization of the services is usually associated with the critique of the commodification of the good. This paper makes a conceptual distinction between both processes, reflecting on the case of the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil. -

(Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú

Indice Diagnostico Ambiental del Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopo-Salar de Coipasa (Sistema TDPS) Bolivia-Perú Indice Executive Summary in English UNEP - División de Aguas Continentales Programa de al Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente GOBIERNO DE BOLIVIA GOBIERNO DEL PERU Comité Ad-Hoc de Transición de la Autoridad Autónoma Binacional del Sistema TDPS Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Departamento de Desarrollo Regional y Medio Ambiente Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos Washington, D.C., 1996 Paisaje del Lago Titicaca Fotografía de Newton V. Cordeiro Indice Prefacio Resumen ejecutivo http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (1 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Antecedentes y alcance Area del proyecto Aspectos climáticos e hidrológicos Uso del agua Contaminación del agua Desarrollo pesquero Relieve y erosión Suelos Desarrollo agrícola y pecuario Ecosistemas Desarrollo turístico Desarrollo minero e industrial Medio socioeconómico Marco jurídico y gestión institucional Propuesta de gestión ambiental Preparación del diagnóstico ambiental Executive summary Background and scope Project area Climate and hydrological features Water use Water pollution Fishery development Relief and erosion Soils Agricultural development Ecosystems Tourism development Mining and industrial development Socioeconomic environment Legal framework and institutional management Proposed approach to environmental management Preparation of the environmental assessment Introducción Antecedentes Objetivos Metodología Características generales del sistema TDPS http://www.oas.org/usde/publications/Unit/oea31s/begin.htm (2 of 4) [4/28/2000 11:13:38 AM] Indice Capítulo I. Descripción del medio natural 1. Clima 2. Geología y geomorfología 3. Capacidad de uso de los suelos 4. -

Water Footprint Assessment of Bananas Produced by Small Banana Farmers in Peru and Ecuador

Water footprint assessment of bananas produced by small banana farmers in Peru and Ecuador L. Clercx1, E. Zarate Torres2 and J.D. Kuiper3 1Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment (TASTE Foundation), Koopliedenweg 10, 2991 LN Barendrecht, The Netherlands; 2Good Stuff International CH, Blankweg 16, 3072 Ostermundigen, Bern, Switzerland; 3Good Stuff International B.V., PO Box 1931, 5200 BX, s’-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands. Abstract In 2013, Good Stuff International (GSI) carried out a Water Footprint Assessment for the banana importer Agrofair and its foundation TASTE (Technical Assistance for Sustainable Trade & Environment) of banana production by small farmers in Peru and Ecuador, using the methodology of the Water Footprint Network (WFN). The objective was to investigate if the Water Footprint Assessment (WFA) can help define strategies to increase the sustainability of the water consumption of banana production and processing of smallholder banana producers in Peru and Ecuador. The average water footprint was 576 m3 t-1 in Ecuador and 599 m3 t-1 for Peru. This corresponds respectively to 11.0 and 11.4 m3 per standard 18.14 kg banana box. In both samples, approximately 1% of the blue water footprint corresponds to the washing, processing and packaging stage. The blue water footprint was 34 and 94% of the total, respectively for Ecuador and Peru. This shows a strong dependency on irrigation in Peru. The sustainability of the water footprint is questionable in both countries but especially in Peru. Paradoxically, the predominant irrigation practices in Peru imply a waste of water in a context of severe water scarcity. The key water footprint reduction strategy proposed was better and more frequent dosing of irrigation water. -

Hydro-Social Permutations of Water Commodification in Blantyre City, Malawi

Hydro-Social Permutations of Water Commodification in Blantyre City, Malawi A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Isaac M.K. Tchuwa School of Environment Education and Development Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 List of Figures ................................................................................................................. 6 List of Tables ................................................................................................................... 7 List of Graphs ................................................................................................................. 7 List of Photos .................................................................................................................. 8 List of Maps .................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract ......................................................................................................................... 10 Declaration .................................................................................................................... 11 Copyright Statement .................................................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... -

Water a Right Not a Commodity.Pdf

WATER, A RIGHT NOT A COMMODITY JAUME DELCLÒS (coord.) WATER, A RIGHT NOT A COMMODITY PROPOSALS FROM CIVIL SOCIETY FOR A WATER PUBLIC MODEL This book has been printed in 100% Ancient Forest Friendly paper from sustainable forests. The production process is TCF (Total Clorin Free) in order to collaborate with a forest manage- ment respectful with the environment and economically sustainable. This book has the support of: Cover design: Laura Niubó. © Pedro Arrojo Agudo, José Esteban Castro, Vicky Cann, Eloi Badia, Lluís Basteiro, Ana Gris, Lluís Basteiro, Maude Barlow, Philipp Terhorst, Jaume Delclòs, Ayats, Adriana Marquisio, Al-Hassan Adam, José Esteban Castro, Josep Centelles, Olivier Hoedeman, Silvano Silvério da Costa, Carlos Crespo. © This edition First published: March 2009. ISBN: Legal deposit: Typesetting: Printed by Printed in Spain. Total o partial reproduction prohibited. CONTENTS Foreword 9 I. Type and roots of conflict over water in the world,Pedro Arrojo Agudo 11 II. Notes on the commodification process of water: a review of privatization from a historical perspective, José Esteban Castro 39 III. The role of donors and its support to promote water privatization in developing countries, Vicky Cann 61 IV. The failure of water privatization, Eloi Badia, Lluís Basteiro and Ana Gris 79 V. The inclusion of water in the General Agreement on Trade in Services, Lluís Basteiro 103 VI. The right to water, Maude Barlow 113 VII. Politicizing participation in urban water services, Philipp Terhorst 129 VIII. Public management with a social participation and control towards the water as a Human Right, Jaume Del- 7 clòs and Ayats 143 IX. -

The Commodification of the Public Service of Water: a Normative Perspective Adrian Walsh University of New England

Public Reason 3 (2): 90-106 © 2011 by Public Reason The Commodification of the Public Service of Water: A Normative Perspective Adrian Walsh University of New England Abstract. This paper examines some key normative issues that arise from the commodifica- tion of the public supply of water. Since the end of World War Two, the provision of water for domestic consumption has, in most Western countries, been regarded as a fundamental public service and, as such, has typically been supplied by the State cheaply or free of charge to users. (Water for agricultural and industrial purposes has also often been so provided.) However, in recent times, in many parts of the world, water markets have been established. This clearly has distributive implications and, potentially, depending upon one’s theoretical framework, raises problems of distributive justice. However, questions concerning the proper distribution of wa- ter have garnered little attention from political philosophers and applied ethicists, nor has there been much discussion of the moral permissibility of commodifying water. This is surprising given the centrality of water to human civilisation. In the early sections of the paper I outline several of the normative and conceptual puzzles surrounding water. I then explore a number of plausible objections that might be raised against commodifying water and consider what role they should play in our all-things-considered judgments about the moral permissibility of water markets. I conclude with some reflections on the role of philosophical inquiry in applied public policy-making. Key words: commodification, water, distributive justice, public services, environmental values. I. CommodIficatIon, Water, and PhIlosoPhy Water is a fundamental human good that many contemporary governments supply for domestic use as well as for both agricultural and industrial purposes. -

Privatisation of Water

Forthcoming in: International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice The Commodification and Exploitation of Fresh Water: Property, Human Rights and Green Criminology Hope Johnson, Nigel South and Reece Walters Abstract In recent years, both developing and industrialised societies have experienced riots and civil unrest over the corporate exploitation of fresh water. Water conflicts increase as water scarcity rises and the unsustainable use of fresh water will continue to have profound implications for sustainable development and the realisation of human rights. Rather than states adopting more costly water conservation strategies or implementing efficient water technologies, corporations are exploiting natural resources in what has been described as the “privatization of water”. By using legal doctrines, states and corporations construct fresh water sources as something that can be owned or leased. For some regions, the privatization of water has enabled corporations and corrupt states to exploit a fundamental human right. Arguing that such matters are of relevance to criminology, which should be concerned with fundamental environmental and human rights, this article adopts a green criminological perspective and draws upon Treadmill of Production theory. Keywords Green criminology, eco-crime, Treadmill of Production, bottled water, water governance, water privatization, water security Introduction ‘On 28 July 2010, through Resolution 64/292 , the United Nations General Assembly explicitly recognized the human right to water and sanitation and acknowledged that clean drinking water and sanitation are essential to the realisation of all human rights.’ (United Nations, 2013). 1 Conflicts over fresh water, notably in arid regions such as the Middle East and Africa, have occurred for thousands of years (Barnaby, 2009; Pacific Institute, 2014). -

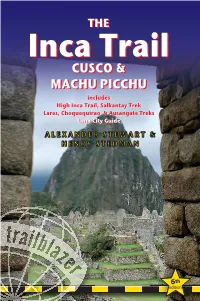

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels, -

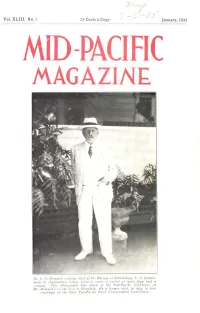

Midpacific Volume43 Issue1.Pdf

Vol. XLIII. No. 1 25 Cents a Copy January, 1932 MID-PACIFIC MAGAZINE Dr. L. 0. Howard, retiring chief of the Bureau of Entomology, U. S. Depart- ment of Agriculture, whose services cover a period of more than half a century. This photograph was taken at the Pan-Pacific Clubhouse on Dr. Howard's recent visit to Honolulu. On a former visit, in 1924, he was chairman of the First Pan-Pacific Food Conservation Conference. -W/r(4`d Indnal./L1LIRnrii RrARTIDLIRRTRRTinnoLu 4. t 04r filliii-ilartfir filaga3tur CONDUCTED BY ALEXANDER HUME FORD Volume XLIII Number 1 • CONTENTS FOR JANUARY, 1932 . 1 . 4, Scientific Problems of the Pineapple Industry - - - 3 4 By Dr. Royal N. Chapman 1 X' All About Bamboo 9 . Rice 15 1 L By Dr. F. G. Krauss el • i • Problems in Copra Industry 19 . • Irrigation in Peru 25 • By C. W. Sutton • . • • ! Some General Information on Panama 33 i By Rene C. Reynolds • r • );.,.. Cinchona, A Tree That Has Altered Maps - - - 41 • g 1• .1 .1 • Cinchona Culture in Java 43 . ri An Excursion to the Riu-Kiu Islands 49 1 • By P. J. Schmidt ,.4.. The Production and Marketing of Diatomaceous Earth - 55 By A. L. Lomax 1 59 l4 The Eel in Japan 5 I '. Frogs in Hawaii 61 . By E. H. Bryan, Jr. ■ 1 • Bulletin of the Pan-Pacific Union, New Series No. 143 - 65 :4. ICI. • Journal of the Pan-Pacific Research Institution, Vol. VII, No. 1. ., ,,,.._ agazine ,„; Gip fi: id-farifir n '-= Published monthly by ALEXANDER HUMS FORD, Pan-Pacific Club Building, Honolulu, T. -

To See Saeed Khan's Water Rights Paper

Coordinated Attacks on Human Rights Through Sovereign and Corporate Complicity on Water Exploitation: The Case of American Government Action and Nestlé The United Nations General Assembly, in 2010, declared access to safe and clean drinking water to be a human right. One of the greatest threats to this fundamental right is the complicity of sovereign and corporate forces seeking to commodity water and deprive populations of their access to that precious resource. The Swiss conglomerate Nestlé has a global reach that impacts several sectors, including water. In fact, Nestlé is the world’s largest producer of bottled water. Yet, Nestlé is able to coordinate with willing and eager governments to extract financial and tax benefits while even availing the legal system to prevent local communities access to their own water supply. In Pakistan, for example, Nestlé digs wells at inaccessible depths to allow them exclusive access to water for bottling while preventing villagers from obtaining potable water. Such action may be properly framed as a form of new colonialism, whereby local populations are denied their own resources by their governments and corporate interests. In the U.S. State of Michigan, Nestlé extracts 130 million gallons of fresh water annually for its bottle water industry; the state government charged the company a permit fee of only $200 per annum to do so. At the same time, Nestlé files lawsuits against local communities to deny them access to their own water supply. The same Michigan government has been allegedly responsible, either through gross negligence or otherwise, for the catastrophic impact caused by the 2015 Flint Water Crisis, where thousands of residents, mostly people of colour, continue to suffer a lack of clean, safe water and for whom the costs to physical, mental and cognitive health will be at a generational scale. -

Changing Water Use and Management in the Context of Glacier Retreat: a Case Study of the Peruvian Village of Huashao”

“Changing water use and management in the context of glacier retreat: a case study of the Peruvian village of Huashao” Susan Conlon January 2018 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of East Anglia, School of International Development © "This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract In Peru´s Callejón de Huaylas, the physical and social dynamics of water use and management are changing rapidly. A shift from subsistence to commercial crop production in comunidades campesinas is leading to intensive water use, compounding the impacts of glacier retreat on water availability. The 2009 Water Resources Law aims to address water scarcity and conflict though ‘formalising’ water use and management, bringing increased state control over water user organizations. This study explores how villagers in a water user organization in Huashao interacted with state discourses and practices of ‘formalization’. It uses discourse analysis to examine ‘formalization’ and its relationship to changing policies at the national and global levels. Through an ethnographic case study, it explores villagers’ everyday water use practices and the outcomes for social and institutional relationships. It investigates changing water use and management, the role of water users in shaping these changes and the influence of historical interactions with the market and NGO initiatives. The thesis shows that globalized discourses of water scarcity and climate change adaptation travel from global to local levels to subtly disperse state control over local water use and management.