Paintings of Jahangir's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glorifying History of Golconda Fort

High Technology Letters ISSN NO : 1006-6748 The Glorifying History of Golconda Fort Dr.K.Karpagam, Assistant Professor, Department of History, D.G.Government Arts College for Women, Mayiladuthurai, Nagapattinam District – 609001 Abstract India is a vast country with a lot of diversity in her physical and social environment. We see people around us speaking different languages, having different religions and practising different rituals. We can also see these diversities in their food habits and dress patterns. Besides, look at the myriad forms of dance and music in our country. But within all these diversities there is an underlying unity which acts as a cementing force. The intermingling of people has been steadily taking place in India over centuries. A number of people of different racial stock, ethnic backgrounds and religious beliefs have settled down here. Let us not forget that the composite and dynamic character of Indian culture is a result of the rich contributions of all these diverse cultural groups over a long period of time. The distinctive features of Indian culture and its uniqueness are the precious possession of all Indians. Significance : The art and architecture of a nation is the cultural identity of the country towards the other countries and that's why the country which has a beach art and architecture is always prestigious to the other countries. The architecture of India is rooted in its history, culture and religion. Among a number of architectural styles and traditions, the contrasting Hindu temple architecture and Indo- Islamic architecture are the best known historical styles. Both of these, but especially the former, have a number of regional styles within them. -

THE ROLE of the MUJTAHIDS of TEHRAN in the IRANIAN CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION 1905-9 Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. By

THE ROLE OF THE MUJTAHIDS OF TEHRAN IN THE IRANIAN CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION 1905-9 Thesis submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. by Vanessa Ann Morgan Martin School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1984 ProQuest Number: 11010525 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010525 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 - 1 - ABSTRACT The thesis discusses the role of the mujtahids of Tehran in the Constitutional Revolution, considering their contribution both in ideas and organisation. The thesis is divided into eight chapters, the first of which deals with the relationship between the Lulama and the state, and the problem of accommodation with a ruler who was illegitimate according to Twelver Shi'ite law. The second chapter discusses the economic and social position of the Lulama, concentrating on their financial resources, their legal duties, and their relationships with other groups, and attempting to show the ways in which they were subject to pressure. In the third chapter, the role of the ^ulama, and particularly the mujtahids, in the coming of the Revolution is examined, especially their response to the centralisation of government, and the financial crisis at the turn of the century. -

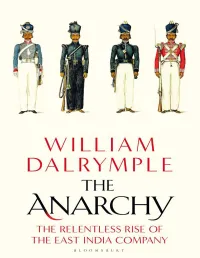

The Anarchy by the Same Author

THE ANARCHY BY THE SAME AUTHOR In Xanadu: A Quest City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium The Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India Begums, Thugs & White Mughals: The Journals of Fanny Parkes The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi 1857 Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857 (with Yuthika Sharma) The Writer’s Eye The Historian’s Eye Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond (with Anita Anand) Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company 1770–1857 Contents Maps Dramatis Personae Introduction 1. 1599 2. An Offer He Could Not Refuse 3. Sweeping With the Broom of Plunder 4. A Prince of Little Capacity 5. Bloodshed and Confusion 6. Racked by Famine 7. The Desolation of Delhi 8. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings 9. The Corpse of India Epilogue Glossary Notes Bibliography Image Credits Index A Note on the Author Plates Section A commercial company enslaved a nation comprising two hundred million people. Leo Tolstoy, letter to a Hindu, 14 December 1908 Corporations have neither bodies to be punished, nor souls to be condemned, they therefore do as they like. Edward, First Baron Thurlow (1731–1806), the Lord Chancellor during the impeachment of Warren Hastings Maps Dramatis Personae 1. THE BRITISH Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive 1725–74 East India Company accountant who rose through his remarkable military talents to be Governor of Bengal. -

Dramatis Personae (Major Figures and Works)

Dramatis Personae (Major Figures and Works) Sirāj al-Dīn ‘Alī Khān “Ārzū” (1689–1756 AD/1101–69 AH) Born to a lineage of learned men descended from Shaykh Chiragh Dihlavi and Shaykh Muhammad Ghaws Gwaliori Shattari, Arzu was raised and edu- cated in Gwalior and Agra. In 1719–20 AD/1132 AH, he moved to Delhi, where he was at the center of scholarly and literary circles. An illustrious scholar, teacher, and poet, he wrote literary treatises, commentaries, poetic collections (dīvāns), and the voluminous commemorative biographical compendium (tazkirih), Majma‘ al-Nafa’is (1750–51 AD/1164 AH) centered on Timurid Hin- dustan. He was teacher to many Persian and Urdu poets, and his position on proper idiomatic innovation was central to the development of north In- dian Urdu poetic culture. Arzu’s main patron was Muhammad Shah’s khān-i sāmān, Mu’tamin al-Dawlih Ishaq Khan Shushtari, and then his eldest son, Najam al-Dawlih Ishaq Khan. Through Ishaq Khan’s second son, Salar Jang, Arzu moved to Lucknow under Shuja‘ al-Dawlih’s patronage in 1754–55, as part of the migration of literati seeking patronage in the regional courts after Muhammad Shah’s death. Arzu died soon after in 1756, and his body was transported back to Delhi for burial. xvi Dramatis Personae Mīr Ghulām ‘Alī “Āzād” Bilgrāmī (1704–86 AD/1116–1200 AH) He was a noted poet, teacher, and scholar (of Persian and Arabic). Born into a scholarly family of sayyids in the Awadhi town of Bilgram, his initial edu- cation was with his father and his grandfather, Mir ‘Abd al-Jalil Bilgrami. -

Riding Through Change History, Horses, and the Restructuring of Tradition in Rajasthan

Riding Through Change History, Horses, and the Restructuring of Tradition in Rajasthan By Elizabeth Thelen Senior Thesis Comparative History of Ideas University of Washington Seattle, Washington June 2006 Advisor: Dr. Kathleen Noble CONTENTS Page Introduction……………………………………………………………………… 1 Notes on Interpretation and Method History…………………………………………………………………………… 7 Horses in South Asia Rise of the Rajputs Delhi Sultanate (1192-1398 CE) Development of Rajput States The Mughal Empire (1526-1707 CE) Decline of the Mughal Empire British Paramountcy Independence (1947-1948 CE) Post-Independence to Modern Times Sources of Tradition……………………………………………………………… 33 Horses in Art Technical Documents Folk Sayings and Stories Col. James Tod Rana Pratap and Cetak Building a Tradition……………………………………………………………… 49 Economics Tourism and Tradition Publicizing Tradition Breeding a Tradition…………………………………………………………….. 58 The Marwari Horse “It's in my blood.” Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….. 67 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………… 70 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. District Map of Rajasthan…………………………………………………… 2 2. Province Map of India………………………………………………………. 2 3. Bone Structure in Marwari, Akhal-Teke and Arab Horses…………………. 9 4. Rajput horse paintings……………………………………………................. 36 5. Shalihotra manuscript pages……………………………………………….... 37 6. Representations of Cetak……………………………………………………. 48 7. Maharaj Narendra Singh of Mewar performing ashvapuja…………………. 54 8. Marwari Horses……………………………………………………………… 59 1 Introduction The academic discipline of history follows strict codes of acceptable evidence and interpretation in its search to understand and explain the past. Yet, what this discipline frequently neglects is an examination of how history informs tradition. Local knowledge of history, while it may contradict available historical evidence, is an important indicator of the social, economic, and political pressures a group is experiencing. History investigates processes over time, while tradition is decidedly anachronistic in its function and conceptualization. -

Supreme Court of India

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA LIST OF BUSINESS PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA FOR MONDAY 01ST MAY 2017 [Website : http://sci.nic.in] FINAL LIST SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 2 of 122 MONDAY 01ST MAY 2017 FINAL LIST SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 3 of 122 MONDAY 01ST MAY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF BUSINESS MONDAY 01ST MAY 2017 COURT NO CORAM 1 [SPECIAL BENCH AT 10.30 A.M.] BEFORE : HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE J. CHELAMESWAR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RANJAN GOGOI HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE MADAN B. LOKUR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PINAKI CHANDRA GHOSE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE KURIAN JOSEPH HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE........................................................................................................................ 6 HON'BLE DR. JUSTICE D.Y. CHANDRACHUD HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJAY KISHAN KAUL 2 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA........................................................................................................ 14 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.M. KHANWILKAR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE MOHAN M. SHANTANAGOUDAR BEFORE : HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.M. KHANWILKAR . [CHAMBER MATTERS] 3 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE J. CHELAMESWAR............................................................................................... 23 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE S. ABDUL NAZEER [SPECIAL BENCH AT 2. 00 P.M.] BEFORE : HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE J. CHELAMESWAR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE ABHAY MANOHAR SAPRE 4 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RANJAN GOGOI.................................................................................................... 31 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE NAVIN SINHA BEFORE : HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE NAVIN SINHA . [IN-CHAMBER MATTERS] 5 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE MADAN B. LOKUR................................................................................................41 HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE DEEPAK GUPTA [SPECIAL BENCH AT 2. 00 P.M.] BEFORE : HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE MADAN B. -

List of Candidates for the Post of Lab Engineer Department of Electrical Engineering

List of candidates for the post of Lab Engineer Department of Electrical Engineering S. NO NAME FATHER’S NAME 1 Muhammad Ilyas Faqir Said Eligible 2 Hassan Jalil Abdul Jalil Eligible 3 Muhammad Junaid Khan Bakht Jehan Khan Eligible 4 Abdul Qayum Khan Wakeel Khan Eligible 5 Muhammad Noman Khan Muhammad Shafiq Eligible 6 Aitizaz Ali Riaz Ali Eligible 7 Asad Khan Mukamil Khan Eligible 8 Muhammad Suleman Malik Malik Khuda Bakhsh Eligible 9 Tauseef Ahmad Munawar Gul Inelligible low gpa 10 Imtiaz Ahmad Azar Khan Naseem Eligible 11 Hamza Mustajab Muhammad Mustajab Khan Eligible 12 Muhammad Haider Nazir Nazir Ud Din Eligible* Degree missing 13 Muhammad Uzair Shah Khan Sharaf Eligible 14 Aminullah Qurasan Khan Eligible 15 Faiz Ur Rehman Noor jamal Eligible 16 Tauqir Ahmad Sardaraz Khan Eligible 17 Mohammad Ihsan Mohammad Younas Eligible 18 Waleed Muhamad Tariq Eligible 19 Zubair Ibrahim Sardar Muhammad Ibrahim Eligible 20 Kiran Asif Shah Eligible 21 Muhammad Idrees Umar Hassan Eligible 22 Lal Said Khan Sahib Eligible 23 Sara islam Nazar ul Islam Eligible 24 Muhammad Anis Khaliq Dad Eligible* PEC, Degree Missing 25 Abbas Mukhtar Muhktiar Ali Eligible 26 Muhammad Azaz Ihsan Ullah Eligible 27 Sajad ullah Rafiq Ahmad Eligible 28 Jawad Ul Islam Fazli Rabbi Eligible 29 Muhammad Ashfaq Faqir Khan Eligible 30 Adil Khan Jamshed Khan Eligible 31 Sohail Hamid Buneri Hamid Gul Eligible 32 Attullah Taj Uddin Eligible 33 Muhammad Shahzad Khan Ashraf Khan Eligible 34 Faisal Maqbool Maqbool Islam Eligible 35 Shifaat Ur Rehman Unar Farooq Eligible 36 Saddam Hussain Muhammad Azam Eligible 37 Syed Noman Syed Nadir Shah Eligible 38 Owais Khan Muhammad Riaz Khan Eligible 39 Muhammmad Fawad Muhammad Jehangir Eligible* PEC Card missing 40 Waqar Ali Muhammad Sher Eligible 41 Abdullah Qayyum Abdul Gayyum Eligible Engr. -

Life Science Journal 2014;11(10S) 47 A

Life Science Journal 2014;11(10s) http://www.lifesciencesite.com A Study on the Effect of Indian Literature through Translation into Persian Language in Iran Moloud shagholi MA in English Translation, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, East Azarbaijan, Iran [email protected] Abstract: Relations, interactions, and cultural commonalities of Iran and India date back to more than three thousand years before and Aryans immigration. The evidence of this claim in the ancient era is the mythical commonalities. The relations of Iran and the Indian subcontinent, before Islam, have been based on common race, common language, and common customs. Iran and Indian subcontinent established through Dari Persian language the same relation that had established through Pahlavi, Avestan and Sanskrit languages before Islam. Translation and gaining alien words and translative interpretations are bred by clash of languages with together which stems from clash of cultures, and this clash and bind of cultures and languages with together is a quite natural and inevitable matter; because there is no language and culture that has not been influenced by other languages and cultures yet its intensity varies. As a language is richer and more powerful in terms of scientific, cultural, economic, and social aspects, it lends more words and concepts to other languages; and as a nation is more dependent upon another country in terms scientific, technical, economic, and political matters, it borrows more words and concepts from that country. This paper will study the probable effect of Indian literature on the Persian language from the perspective of translation. [Moloud shagholi. A Study on the Effect of Indian Literature through Translation into Persian Language in Iran. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

S. No. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders without / invalid CNIC # as of 31-12-2019 S. Folio No. Security Holder Name Father's/Husband's Name Address No. of No. Securities 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN S/O MR. MOHAMMAD WAZIR KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI S/O MR. MOHD ABDUL HAFEEZ 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3,280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN S/O MURTUZA MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD MR. HAMID HUSSAIN C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE S/O A. RAHIM B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9,382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED S/O GHULAM QADDIR KHAN H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN S/O MOHD NASRULLAH KHAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA S/O FAZAL-I-MAHMOOD 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1,919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN S/O ABDUR REHMAN KHAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8,530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN SARDAR M. FAROOQ IBRAHIM 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5,945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN S/O KH. -

TYBA SEM 6 History of Medieval India QUESTIONS Whom Did Babur

TYBA SEM 6 History of Medieval India QUESTIONS Whom did Babur defeat in the battle of Gogra? Which section of the army was given the credit of victory at Panipat to Babur? Name the ruler of Gujarat who was defeated by Akbar in 1572. The first revolt of Shah Jahan's reign was that of: Sher Shah was succeeded by: Prince Khurram was given the title of: Babur was originally the ruler of: How many years did Humayun spend in exile after he lost his kingdom in India? The title of Alamgir was assumed by: The battle between Babur and Rana Sanga was fought at: Akbar fought the Battle of Haldighati with: Sher Shah's last military expedition was directed against: The second Battle of Panipat in 1556 was fought between: Which king of the Marathas was executed by Aurangzeb? Akbar's revenue organisation was based on that of ------- Who organised Akbar's Land Revenue system? Land that was cultivated through the year was called -----. Zabti and Ghallabakshi were forms of --------- Which Mughal king revived the Jizya tax in the 17th century? The Emperor dispensed justice in the -----. Which courts did the Qazis dispense justice according to the Sharia? The Qazi-i-Laskar was in charge of ---- law. The Mughal administration was run by a bureaucracy consisting of different grades of military officers known as: The Mughal Emperor ------ introduced the Mansabdari system. During the reign of Akbar, the mansab of ------ and above was reserved for members of royal family. The --- rank was the personal rank of the mansabdar. The startegically important fort of -

Rulings of the Chair (1999-2017)

1037(18)NA. On PC-9 By Shoaib.M NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN RULINGS OF THE CHAIR 1999-2017 i Copyright: © 2017 by National Assembly Secretariat, Islamabad. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any mean, or stored in data base or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. Title: Rulings of the Chair Compiled, emended Muhammad Saleem Khan & edited by: Deputy Secretary (Legislation) Abdul Majeed Senior Official Reporter (English) Composing & Designing Layout Javed Ahamad Data Processing Assistant Copies: 500 Printed: Pakistan Printing ii PREFACE Rulings, decisions and observations made by the Chair from time to time on different issues play important role in the parliamentary history. They set precedent which gives guidance to subsequent Speakers, members and officers. The instant publication “Rulings of the Chair” consists of decisions taken by the Chair extracted and compiled from the printed debates of the National Assembly for the years 1999-2017.These decisions either involve an interpretation of rule or conduct or any new situation, seeking clarification or ruling of the Chair. Previous compilation “Decisions of the Chair” covers decisions/rulings of the Chair from 1947-1999. For the facility of the reader and to locate the Rulings subject-wise and for ready reference a table of contents and an exhaustive index has been added to the said publication. We are deeply indebted to honourable Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, Speaker, National Assembly, Secretary, Ministry of Law and Justice, Mr. Karamat Hussain Niazi, Special Secretary, Mr. Qamar Sohail Lodhi and Mr. Muhammad Mushtaq Additional Secretary(Legislation) National Assembly Secretariat, who took personal interest in the accomplishment of this difficult task.