Influenza Epidemic in Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

The Weather and Circulation of December 1968

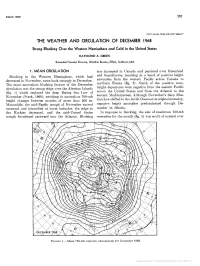

March 1969 281 UDC 551.515.72:551.513.2(73)“1968.12” THEWEATHER ANDCIRCULATION OF DECEMBER 1968 Strong Blocking Over the Western Hemisphere and Cold in the United States RAYMOND A. GREEN Extended Forecast Division, Weather Bureau, ESSA, Suitland, Md. 1. MEAN CIRCULATION also increased inCanada and persisted over Greenland Blocking inthe WesternHemisphere, which had and Scandinavia, resulting in a band of positive height decreased in November, came back strongly in December. anomalies from the western Pacific across Canada to The most anomalous blocking feature of the December northernRussia (fig. 2). South of the positive zone, circulation was the strong ridge over the Aleutian Islands height departures were negative from the eastern Pacific (fig. 1) which replaced the deepBering Sea Low of across theUnited States and from the Atlantic to the November (Stark, 1969)’.resulting in anomalous 700-mb eastern Mediterranean. Although November’s deep Sibe- height changes betweenmonths of more than 200 m. rian Low shifted to the Arctic Ocean at itsoriginalintensity, Meanwhile, the mid-Pacific trough of November moved negativeheight anomalies predominatedthrough De- eastward and intensified at lower latitudes, the ridge in cember in Siberia. the Rockies decreased, andthe mid-United States In response to blocking, the axis of maximum 700-mb troughbroadened eastward intothe Atlantic. Blocking westerlies for the month (fig. 3) was south of normal over FIGURE1.-Mean 700-mb contours (decameters) for December 1968. Unauthenticated | Downloaded 10/02/21 09:23 AM UTC 282 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Vol. 97,No. 3 FIGURE 3.-Mean 700-mbwind speed (meters per second) for FIGURE2.-Departure from normal of mean 700-mb height (dec- December ,1968. -

August, 1968 Operating Engineers, AFL-CIO

·Master Tech Pact Now Ratified "Serving ·the_men who move the ear!h!" \ * * * 0 ENGINEERS· 'NEWS Union Gains Top PUBLISHED TO PROMOTE THE GENERAL WELFARE OF ALL ENGINEERS AND THEIR FAMILIES • Wage Agreement GUAM, WHERE AMERICA'S DAY BEGINS HAWAII, THE 50T H STATE NORTHERN CAliFORNIA, THE GOLDEN STATE NORTHERN N EVADA, SILVER STATE UTAH. HEART OF THE ROCKIES One of the best Technical Engineer Master Agreements ever ne 1, ,.· gotiated went on the books this month following ratification by members of Operating Engineers Local Union No. 3, International Union of Vol. 27-No. 8 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA ~® August, 1968 Operating Engineers, AFL-CIO. The new agreement will cover mem bers working in the forty-six Northern California counties and Northern Nevada. International Vice President and Local 3 Business Manager AI Clem said the new contract went into effect the 1st of August, 1968 and would expire on the 15th of June, 1971. Mr. Clem said he felt both signatories, Bay Counties Civil Engineers & Land Surveyors Associa tion, Inc. and the union, had worked hard to hammer out a, fair Master Agreement. "We are satisfied that this is a contract that both the union and the employer can live with," said Clem, "and our main objective now is to • advocate at every level of government and industry the need for non stop construction programs that will keep our .economy moving ahead and provide jobs for all our members." Local 3 President Paul Edgecombe worked diligently and on a very short deadline to gain current coverage for the city and county person nel working within the jurisdiction of the new technical agreement. -

UNITED NATIONS Distr

UNITED NATIONS Distr. GENERAL GENERAL A/7753 ASSEMBLY 7 November 1969 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH THenty-fourth session Agenda item 63 INFORMJ;TION FROM NON-SELF-GOVERNING TERRITORIES TRANSMITTED UNDER !IRTICLE 73 e OF THE CHAR·TER Report of the Secretary-General l. Under the terms oi' Article 73 e of the Charter of the United Nacions, Member States vhich have or assume responsibilities for the ac1:ninistration of Territories whose peoples have no,; yet attained a full meocsure of self -government cmdertake to transmit regularly to the Secretary-Geners.l infol~mation relatine; to economic, social and educationsl conditions ifl the TerJ.."itories for 1.;hich they are reS)Otlsible, other than those Territories to which che International Trusteeship SJcscem applies. In addition, the General Assembly in several r·esolutions, the most recent of which was resolution 2L,22 (XXIII) of' 18 Dece c;;:.er 1968, urged the e.dministerin:o Pm<ers concerned nto transn1it, or continue to transmit, to the Secretary-Genel.... e.l the information p:!:"escribed in Article 73 e of the Charter, as well as the f'J.ll_est possible inforw.ation on political and constitutional developments in -~he 11 Territories concerned .. 2. The table annexed to the present report sh()';IS the dates on \·lhich information called for in Article 73 e was transmitted to the Secretary-General in respect of the years 1967 and 1958 up to 3 November 1969. 3. The information transmitted under Article 73 e of the Charter follows in general the standard form approved b:r the General Assembly and incLudes information on geography, history, population, economic, social and educational conditions. -

Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts

[ORIGINAL AGREEMENT] VIEW TEXT: English French Other Title: MULTILATERAL: Agreement on the rescue of astronauts, the return of astronauts and the return of - objects launched into outer space.Opened for signature at Washington, London and Moscow on 22 April 1968 Came into force on 3 December 1968, the date of deposit of the instruments of ratification by five Governments including the Governments designated as Depositary Governments under paragraph 2 of article 7, i.e., the Governments of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom of Great Britainand Northern Ireland and the United States of America, in accordance with paragraph 3 of the same article. Instruments of ratification or accession ( a ) were deposited on the dates indicated as follows: State Date of deposit of the instrument ofratification or accession in London (L) Moscow (M) or Washington (W Registration Number: 9574 REGISTERED By: Union of Soviet Socialist Republics AND United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland AND United States of America Date: 15.05.1969 Signed/Adopted: 22.04.1968, WASHINGTON Entry Into Force: 03.12.1968 DEFINITIVE ICJ: No Authority - PARTICIPATION . _r.-.___ .--.-.. ~-.---1_--- ..-- ______l_..-___l_-____ ____________._I.. ___-____c -__ ii PARTICIPANT ;I;i ACTION ‘[DATE ii WITH EFFECT i:: :. I................................ 5 ;j\r ij I ii ii ;; TERRITORIAL ;; British Solomon Islands ; 03.12.1968 ;j:i 03.12.1968 ii ;/ APPLICATION ii .,..................................................................................................................................,....................................................................................:\ -

16004670.Pdf

SEMIANNUALHISTORICAL REPORT&> HEADQUARTERS FIEXD COMMAND DEFENSE ATOMIC. SUPPORT AGENCY SANDIA BASE, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO Activities for the Period 1 July 1968 - 31 December 1968 Other Volumes comprising the Field Command, DAsA' . Semiannual Historical Report as of 31 December . ..::... 1968, are as follows: VOLUME I1 - Bossier Base Shreveport , La. VOLUME I11 - Clarksville Base Clarksville, Term. VOLUME IV - Killeen Base Killeen, Texas VOLUME v - Lake'Mead Base Las Vegas , Nevada VOLUME VI - Manzano Base --.A Albuquerque, New Mexico .: _~_..2 .yy: 2 1s VOLUME VI1 - Sandia Base s'.. Albuquerque, New Mexico .: i% HEADQUARTERS FIELD COMMAND DEFENSE ATOMIC SUPPORT AGENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. Headquarters Field Command 1 Secretary to the Staff 4 Equal Employment Opportunity Office 11 Inspector General 16 Judge Advocate 25 Public Information Office 30 Surgeon 35 Safety Engineer 40 Chap lain 44 Headquarters & Headquarters Co., USA Element 46 Naval Administrative Unit 50 1090th USAF Special Reporting Group 56 Hqs Sqn Sec, 1090th USAF SRG 60 Comptroller 63 Adjutant General 90 Intelligence and Security D' Lrectorate 106 Personnel Directorate 111 Joint Personnel Plans & Requirements Office 114 , Army Personnel Division 119 Navy Personnel Division 127 Air Force Personnel Division 130 Civilian Personnel Division 134 Personnel Services Division 145 Logistics Directorate 150 Engineering Division 158 Logistics Division 197 Research and Development Liaison Directorate 215 Stockpile Management Directorate 279 Nuclear Materiel Directorate 300 -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

See bound volume for ^SéS 1 T° of this series for addenda/corrigenda/revisions 2/ -J to this document. fgSïiilGï.tfl) C0T/94/"dd.l GENERAL AGREEMENT ON 22 April 1968 TARIFFS AND TRADE Special Distribution ARRANGEMENT REGàgglNG INTiiaNiiTXONAL TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES Request made by Italy under Article 3 The following communication has been received by the Director-General from the Italian Permanent Mission for notification to the Cotton Textiles Committee. I have the honour to advise you that the consultations requested by the Italian Government with the authorities of the United Arab Republic, under the Geneva Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Cotton Textiles, took place at Rome from 21 to 29 March 1968. The results of these consultations are set forth in an agreement of which I enclose the text, for the information of the Cotton Textiles Committee. ./. COT/94/Add.l Page 2 MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDINGS Reached by Representatives of the Government of Italy and the United rirab Republic Relating to Cotton Textiles The following are the understandings reached between representatives of the Italian Government and the Government of the United Arab Republic with respect to the conclusion of an agreement concerning imports of cotton textiles (Tariff headings Nos. 55.09.71 and .r5.09.72) from the United Lrab Republic. 1. As a temporary moasure the Italian Government limits its imports of cotton textiles (Tariff headings Nos. 55.09.71 and 55-09.72) from the United Arab Republic at a level of 915 tons constituting the eight and a half month period beginning 15 April 1968, ending 31 December 1968, distributed as follows: From 15 April 3.963 to 14 July 1968 - 305 tons; From 15 July 1968 to 14 October 1968 - 305 tons and remaining 305 tors from 15 October to 31 December 1968. -

Commandant's Annual Report, 1968-1969

COMMANDANT'S ANNUAL REPORT 1968-1969 The Judge Advocate General's School United States Army Charlottesville, Virginia Permit me to extend my sincere appreciation for the generous re sponse I have received .. in the development of our JAG School curricula. Because of the outstanding instruction our Thai Judge Advocates have received at the ... School in Charlottesville, I was desirous of obtaining [their] texts [and course] materials [to assist us] ... LTG SUK PERUNAVIN The Judge Advocate General Ministry of Defense Bangkok. Thailand Since its formation, your school has established an enviable record that has earned the respect and admiration of all the services. The manner in which the graduates of the Judge Advocate General's School ;u:complish their varied duties throughout the world reflects greatly on the fullfillment of your mission. DELK M. ODEN Major General, USA Commandant U. S. Army Aviation School I desire to . .. commend you for the outstanding manner in which you are supp0r.ting the United States Army Reserve . .. Your contributions .. are numerous and reflect great initiative . these are the type of activities which confirm the One Army Concept. WILLIAM J. SUTION Major General, USA Chief, Army Reserve The Board is highly impressed with the VISion, dedication and pro fessional attitude of the Commandant and his staff and faculty. They can all take great pride and satisfaction in the excellent academic community which they have maintained at The Judge Advocate General's School. R eport of the Board of Visitors The Judge Advocate General's School, U. S. Army FOREWORD This year, 1969, marks the eighteenth consecutive year of continuous operation of The Judge Advocate General's School in Charlottesville. -

Conference on the Human Environment

United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law DECLARATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON THE HUMAN ENVIRONMENT Following a proposal of the Government of Sweden, formalized in a letter dated 20 May 1968, the Economic and Social Council decided to place the question of convening an International Conference on the Problems of the Human Environment on the agenda of its mid-1968 session (letter dated 20 May 1968 from the Permanent Representative of Sweden addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, E/4466/Add.1). The explanatory memorandum attached to the letter stated that the changes in the natural surroundings, brought about by man, had become an urgent problem for developed as well as developing countries, and that these problems could only be solved through international co-operation. The Swedish Government proposed to convene a conference under the auspices of the United Nations, to work on a solution for the problems of human environment. To assist the Economic and Social Council in its consideration of the question, the Secretary-General prepared a report outlining the work and programmes of the various organizations of the United Nations family, relevant to the problems of the human environment (E/4553). During its mid-1968 session, a draft resolution entitled “Question of convening an international conference on the problems of human environment” was submitted to the Economic and Social Council (E/L.1226). After revision, the Economic and Social Council adopted resolution 1346 (XLV) of 30 July 1968, by which it recommended that the General Assembly include the item entitled “The problems of human environment” in the agenda of its twenty-third session and consider the desirability of convening a conference on problems of the human environment. -

United Nations Treaty Series 1968

464 United Nations Treaty Series 1968 No. 9262. INTERNATIONAL COFFEE AGREEMENT, 1968. OPEN FOR SIGNATURE AT NEW YORK FROM 18 TO 31 MARCH 19681 RATIFICATIONS and ACCESSION (a) Instruments deposited by the following States on the dates indicated : ECUADOR ..... 16 December 1968 NORWAY ..... 23 December 1968 EL SALVADOR . 16 December 1968 PARAGUAY ..... 27 December 1968 HONDURAS .... 16 December 1968 BOLIVIA ...... 30 December 1968 VENEZUELA .... 18 December 1968 COSTA RICA ..... 30 December 1968 CENTRAL AFRICAN FINLAND ...... 30 December 1968 REPUBLIC .... 20 December 1968 GUINEA ...... 30 December 1968 CONGO (REPUBLIC OF) 20 December 1968 NETHERLANDS* (For PANAMA (a) 21 December 1968 the Kingdom in GHANA ...... 23 December 1968 Europe) . 30 December 1968 * With the following statement : " At the llth meeting of the Council of the International Coffee Organization the group of Importing Members jointly expressed the view that Members of the Organization take the greatest possible care not to interfere with freedom of choice in the carriage of coffee while respecting their obligations under the International Coffee Agreement of 1968. " The declared shipping policy of the Netherlands Government is based on the principle of free circulation of shipping in international trade in free and fair competition. In accordance with this principle international transport of coffee should not be made more costly and hampered by discriminatory shipping provisions giving preferences to national shipping. Rather the aim should be that normal commercial considerations should alone determine the method and flag of shipment. " The Government of the Netherlands trusts that the principle of freedom of choice in shipping will be supported and adhered to by all Governments Parties to the International Coffee Agreement of 1968. -

Colorado Heritage Magazine

The Magazine of History Colorado January/February 2015 The 1968 Exhibit Opening February 7 At the History Colorado Center ALSO IN THIS n Colorado Remembers 1968 ISSUE n Marijuana—A Colorado History n Winter Programs Around the State Colorado Heritage The Magazine of History Colorado Edward C. Nichols Steve Grinstead Managing Editor President and CEO Liz Simmons Editorial Assistance History Colorado Center Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer 1200 Broadway Jay DiLorenzo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services Denver, Colorado 80203 303/HISTORY William J. Convery State Historian Administration Public Relations Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by History 303/866-3355 303/866-3670 Colorado, contains articles of broad general and educational Membership Group Sales Reservations interest that link the present to the past. Heritage is distributed 303/866-3639 303/866-2394 bimonthly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to Museum Rentals Archaeology & Historic Preservation institutions of higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented 303/866-4597 303/866-3392 when submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications Research Librarians State Historical Fund office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Publications 303/866-2305 303/866-2825 office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements of Education Support Us fact or of opinion made by contributors. 303/866-4686 303/866-4737 Postage paid at Denver, Colorado All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a History Colorado on the Web benefit of membership. Individual subscriptions are available through the Membership office for $40 per year (six issues). HistoryColorado.org For details about membership write to Membership Office, History Colorado Center, or email us at [email protected]. -

1968 Revisited 40 Years of Protest Movements Edited by Nora Farik

2008 marks the 40th anniversary of the worldwide protests of 1968. In this brochure protagonists of 1968 in Brazil, Poland, the Czech The events of that time such as the protests against the war in Vietnam, Republic, Russia, Germany, South Africa, Serbia and Belgium share the Prague Spring and the student protests in Western Europe and the their memories and assess the events from today’s perspective. U.S. are closely connected – it was truly a global movement! Heinrich Böll Foundation 15 Rue d’Arlon – B-1050 Brussels – Belgium EU Regional Office Brussels Phone (+32) 2 743 41 00 – Fax (+32) 2 743 41 09 – e-mail: [email protected] – www.boell.be ISSUE 7 1968 revisited – 40 years of protest movements ISSUE 7 1968 revisited 40 years of protest movements Edited by Nora Farik Essays and interviews with protagonists of 1968: Teresa Bogucka (Poland), Daniel Cohn-Bendit (France/West Germany), Alexander Daniel (Russia), Benoît Lechat (Belgium), Klaus Meschkat (West Germany), Bill Nasson (South Africa), Nebojša Popov (Yugoslavia), Marcelo Ridenti (Brazil), Wolfgang Templin (East Germany) and Oldrich Tuma° (Czech Republic) 1968 REVISITED 40 YEARS OF PROTEST MOVEMENTS Heinrich Böll Foundation Published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation EU Regional Office Brussels Printed in Belgium, May 2008 © by the authors and the Heinrich Böll Foundation EU Regional Office Brussels All rights reserved English proof-reading and editing: Margaret Cameron and David Fenske French translation: Dimitri Lemaire French proof-reading and editing: Benoit Lechat and Geneviève Warland Final editing: Nora Farik Production: Micheline Gutman Cover picture: © Archive ÚSD The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone.