1968 Revisited 40 Years of Protest Movements Edited by Nora Farik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 30Th Anniversary of June 1976, of the Voivodeship Committee of the Polish United Worker’S Party and Spontaneous

Coins issued in 2006 Coins issued in 2006 National Bank of Poland CoinsCoins – The 30thth Anniversary face value 10 z∏ face value 2 z∏ of June 1976 – metal Ag 925/1000 metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy finish proof finish standard diameter 32.00 mm diameter 27.00 mm weight 14.14 g weight 8.15 g mintage 56,000 pcs mintage 1,000,000 pcs Obverse: An image of the Eagle, established as the State Obverse: An image of the Eagle, established as the State Emblem of the Republic of Poland; on both sides of the Eagle, Emblem of the Republic of Poland. At the top, a semicircular a notation of the year of issue: 20-06. Below the Eagle, an inscription, RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA. On the left-hand side of inscription, Z∏ 2 Z¸. On the rim, an inscription, RZECZPOSPOLITA the Eagle, an inscription, 10, on the right-hand side, an POLSKA, preceded and followed by six pearls. The Mint’s m inscription, Z¸. Below the Eagle, a stylised image of a broken mark,––w , under the Eagle’s left leg. railway track. At the bottom, the notation of the year of issue, m 2006. The Mint’s mark,––w , under the Eagle’s left leg. Reverse: In the central part, an inscription, 1976. Below the inscription, against the background of stylised silhouettes of Reverse: Against the background of a stylised image of two men with their arms raised, on the right-hand side, a cordon of militia officers wearing helmets and shields, a stylised image of a hand. On the left-hand side and at the top, a stylised image of a woman and a boy superimposed. -

Florida Best and Brightest Scholarship ACT Information on ACT Percentile

Florida Best & Brightest Scholarship ACT Information on ACT Percentile Rank In light of the recent Florida legislation related to Florida teacher scores on The ACT, in order to determine whether a Florida teacher scored “at or above the 80th percentile on The ACT based upon the percentile ranks in effect when the teacher took the assessment”, please refer to the following summary. 1. The best evidence is the original student score report received by the teacher 2. If a teacher needs a replacement score report, a. Those can be ordered either by contacting ACT Student Services at 319.337.1270 or by using the 2014-2015 ACT Additional Score Report (ASR) Request Form at http://www.actstudent.org/pdf/asrform.pdf . Reports for testing that occurred prior to September 2012 have a fee of $34.00 for normal processing and can be requested back to 1966. b. The percentile ranks provided on ASRs reflect current year norms, not the norms in effect at the time of testing. c. The following are the minimum composite scores that were “at or above the 80th percentile” at the time of testing based upon the best available historical norm information from ACT, Inc.’s archives. For the following test date ranges: • September, 2011 through August, 2016 : 26 • September, 1993 through August, 2011 : 25 • September, 1991 through August, 1993 : 24 • September, 1990 through August, 1991 : 25 • September, 1989 through August, 1990 : 24 • September, 1985 through August, 1989 : 25 • September, 1976 through August, 1985 : 24 • September, 1973 through August, 1976 : 25 • September, 1971 through August, 1973 : 24 • September, 1970 through August, 1971 : 25 • September, 1969 through August, 1970 : 24 • September, 1968 through August, 1969 : * • September, 1966 through August, 1968 : 25 *ACT, Inc. -

Southeast Asia SIGINT Summary, 7 February 1968

Doc ID: 6637207 Doc Ref ID: A6637206 •• •• • •• • • • • • • ••• • • • • • • 3/0/STY/R33-68 07 February 1968 Dist: O/UT (SEA SIGSUM 33-68) r THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS CODEWORD MATERIAL Declassified and Approved for Release by NSA on 10-17-2018 pursuant to E . O. 13526 Doc ID: 6637207 Doc Ref ID: A6637206 TOP SECR:f:T T1tII'4~ 3/0/STY/R33-68 07 Feb 68 220oz DIST: O/UT NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY SOUTHEAST ASIA SIGINT SUMMARY This report is presented in two sections; Section A summarizes significant developments noted throughout Southeast Asia during the period 31 January - 6 February 1968; Section B summarizes those developments noted throughout Southeast Asia available to NSA at the time of publication on 7 February, All infonnation in this report is based entirely on SIGINT except where otherwise specifically indicated. CONTENTS Situation Summary ..• • t I f • 1l e • ,,_ _, f I' t I • • I' 1 (SECTION A) I. Communist Southeast Asia A. Military Responsive I 1. Vietnamese Communist Communications - South Vietnam . • • • . • • • . 5 2. DRV Communications. • ., • fl f t· C 12 Doc ID: 6637207 Doc Ref ID: A6637206 INon - Responsive I 3/0/STY/R33~68 ·· . C<:>NTE~TS (SECTION B) I. Communist Southeast Asia A. ·· Military 1. Vietnamese Communist Communications - South Vietnam ••••• o ••• o •• 0 • 21 2. DRV Communications. 27 ii TOP SiCR~T TRINE Doc ID: 6637207 Doc Ref ID: A6637206 INon - Re.sponsive I . .. TOP SE:Cltef Tltf?rqE .. 3iO/STY/R33-68 . CONTENTS iii 'fOP ~~Cltr;T TRit~E Doc ID: 6637207 Doc Ref ID: A6637206 TOP SECRET TRINE 3/0/STY/R33-68 SITUATION SUMMARY (SECTION A) During the past week, Vietnamese Communist elements in Military Region (MR) Tri-Thien-Hue have been employing tactical signal plans, a practice which, in the past~ has been indica tive of offensive activity on the part of the units involved. -

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

The 1968 Exhibit Exhibition Walkthrough

CONTACTS: Lauren Saul Sarah Fergus Director of Public Relations Public Relations Manager 215.409.6895 215.409.6759 [email protected] [email protected] THE 1968 EXHIBIT EXHIBITION WALKTHROUGH The year 1968 reverberates with an awesome power down to the present day. A year of violence and upheaval, of intense political divisions, of wars abroad and wars at home. A year of vivid colors, startling sounds, and searing images. A year that marked a turning point for a generation coming of age. A turbulent, relentless cascade of events that changed America forever. The 5,000-foot exhibition is divided chronologically, by months of the year. Each month is themed around key events to highlight the various political, military, cultural, and social shifts that happened that year—from the height of the Vietnam War and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, from the bitter 1968 presidential election to the Apollo 8 mission when humans first orbited the moon. Visitors enter the exhibition gallery through a beaded curtain into an alcove that displays each month of 1968 with a brightly-colored icon. Video footage plays while guests take in famous quotes from the year, before entering into the first month. JANUARY: “THE LIVING ROOM WAR” The immensity of the Vietnam War came crashing into American living rooms in 1968 as it never had before. On the night of January 31—during a cease-fire for Tet, the Vietnamese New Year’s feast—North Vietnamese forces launched a series of bold surprise attacks, striking hundreds of military and civilian targets throughout South Vietnam, including the U.S. -

Campaign 1968 Collection Inventory (**Materials in Bold Type Are Currently Available for Research)

Campaign 1968 Collection Inventory (**Materials in bold type are currently available for research) Campaign. 1968. Appearance Files. (PPS 140) Box 1 (1 of 3) 1968, Sept. 7 – Pittsburgh. 1968, Sept. 8 – Washington, D.C. – B’nai B’rth. 1968, Sept. 11 – Durham, N.C. 1968, Sept. 11 – Durham, N.C. 1968, Sept. 12 – New Orleans, La. 1968, Sept. 12 – Indianapolis, Ind. 1968, Sept. 12 – Indianapolis, Ind. 1968, Sept. 13 – Cleveland, Ohio. 1968, Sept. 13 – Cleveland, Ohio. 1968, Sept. 14 – Des Moines, Ia. 1968, Sept. 14 – Santa Barbara, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – Yorba Linda, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – 17 – Anaheim, Calif. 1968, Sept. 16 – Anaheim, Calif. 1968, Sept. 18 – Fresno, Calif. 1968, Sept. 18 – Monterey, Calif. 1968, Sept. 19 – Salt Lake City, Utah. 1968, Sept. 19 – Peoria, Ill. 1968, Sept. 19 – Springfield, Mo. 1968, Sept. 19 – New York City. Box 2 1968, Sept. 20-21 – Philadelphia. 1968, Sept. 20-21 – Philadelphia. 1968, Sept. 21 – Motorcade : Philadelphia to Camden, N.J. 1968, Sept. 23 – Milwaukee, Wis. 1968, Sept. 24 – Sioux Falls, S.D. 1968, Sept. 24 – Bismarck, N.D. 1968, Sept. 24 – Boise, Idaho. 1968, Sept. 24 – Boise, Idaho. 1968, Sept. 24-25 – Seattle, Wash. 1968, Sept. 25 – Denver, Colo. 1968, Sept. 25 – Binghamton, N.Y. 1968, Sept. 26 – St. Louis, Mo. 1968, Sept. 26 – Louisville, Ky. 1968, Sept. 27 – Chattanooga, Tenn. 1968, Sept. 27 – Orlando, Fla. 1968, Sept. 27 – Tampa, Fla. Box 3 1968, Sept. 30-Oct. 1 – Detroit, Mich. 1968, Oct. 1 – Erie, Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Pa. 1968, Oct. 1 – Williamsburg, Va. 1968, Oct. 3 – Atlanta, Ga. 1968, Oct. 4 – Spartenville, S. -

MPS-0746712/1 the GUARDIAN 18.3.68 Police Repel Anti—War Mob

MPS-0746712/1 THE GUARDIAN 18.3.68 Police repel anti—war mob at US embassy BY OUR OWN REPORTERS Britain's biggest anti-Vietnam war demonstration ended in London yesterday with an estimated 300 arrests: 86 people were treated by the St John Ambulance Brigade for injuries and 50, including 25 policemen, one with serious spine injury, were taken to hospital. Demonstrators and police—mounted and on foot—engaged in a protracted battle, throwing stones, earth, firecrackers and smoke bombs. Plastic blood, an innovation, added a touch of vicarious brutality. It was only after considerable provocation that police tempers began to fray and truncheons were used, and then only for a short time. The demonstrators seemed determined to stay until they had provoked a violent response of some sort from the police. This intention became paramount once they entered Grosvenor Square. Mr Peter Jackson, Labour MP for High Peak, said last night that he would put down a question in the Commons today about "unnecessary violence by police." Earlier in the afternoon, members of the Monday Club, including two MPs, Mr Patrick Wall and Mr John Biggs- Davison, handed in letters expressing support to the United States and South Vietnamese embassies More than 1,000 police were waiting for the demonstrators in Grosvenor Square. They gathered in front of the embassy while diagonal lines stood shoulder to shoulder to cordon off the corners of the square closest to the building. About 10 coaches filled with constables waited in the space to rush wherever they were needed and a dozen mounted police rode into the square about a quarter of an hour before the demonstrators arrived. -

"I AM a 1968 Memphis Sanitation MAN!": Race, Masculinity, and The

LaborHistory, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2000 ªIAMA MAN!º: Race,Masculinity, and the 1968 MemphisSanitation Strike STEVEESTES* On March 28, 1968 Martin LutherKing, Jr. directeda march ofthousands of African-American protestersdown Beale Street,one of the major commercial thoroughfares in Memphis,Tennessee. King’ splane had landedlate that morning, and thecrowd was already onthe verge ofcon¯ ict with thepolice whenhe and other members ofthe Southern Christian LeadershipConference (SCLC) took their places at thehead of the march. The marchers weredemonstrating their supportfor 1300 striking sanitation workers,many ofwhom wore placards that proclaimed, ªIAm a Man.ºAs the throng advanceddown Beale Street,some of the younger strike support- ersripped theprotest signs off the the wooden sticks that they carried. Theseyoung men,none of whomwere sanitation workers,used the sticks to smash glass storefronts onboth sidesof the street. Looting ledto violent police retaliation. Troopers lobbed tear gas into groups ofprotesters and sprayed mace at demonstratorsunlucky enough tobe in range. High above thefray in City Hall, Mayor HenryLoeb sat in his of®ce, con®dent that thestrike wasillegal, andthat law andorder wouldbe maintained in Memphis.1 This march wasthe latest engagement in a®ght that had raged in Memphissince the daysof slaveryÐ acon¯ict over African-American freedomsand civil rights. In one sense,the ª IAm aManºslogan wornby thesanitation workersrepresented a demand for recognition oftheir dignity andhumanity. This demandcaught whiteMemphians bysurprise,because they had always prided themselvesas being ªprogressiveºon racial issues.Token integration had quietly replaced public segregation in Memphisby the mid-1960s, butin the1967 mayoral elections,segregationist candidateHenry Loeb rodea waveof white backlash against racial ªmoderationºinto of®ce. -

Pdf Icon[PDF – 369

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE Health Services and Mental Health Ministration Washington D.C. 20201 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT HeaZkJJzterview SurveyDaiiz VOL. 18, NO. 9 FROM THE SUPPLEMENT I DECEMBER5, 1869 NATIONAL CENTER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS Cigarette Smoking Status-June 1966, August 1967, and August 1968 For the past 3 years the National Center for former smokers among males than among females, Health Statistics has contracted with the U.S. Bureau the proportion of female former cigarette smokers of the Census to include a supplement to the Current is increasing at a faster rate than that of males. From Population Survey on smoking habits in the United June 1966 to August 1968 the proportion of male former States. The first data were collected as a supplement smokers increased by 12 percent and the proportion of to the Current population Survey of June 1966, the female former smokers increased by 22 percent. In second supplement was added to the questionnaire in addition the increase occurred primarily among males August 1967, and the third in August 1968. Similar in the age group 17-24 years while it was spread data were collected during the period July 1964-July throughout all age categories for females. 1966 as a part of the ongoing Health Interview Sur In 1966 an estimated 39.6 percent of the population a vey. (See “Current Estimates from the Health Inter- aged 17 years and over smoked cigarettes; in 1968 the view Survey, United States, 1967,” Vital and Health comparable percentage was 37.7, a drop of 5 percent. -

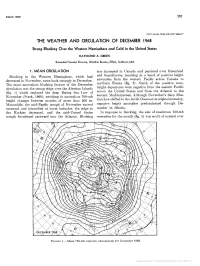

The Weather and Circulation of December 1968

March 1969 281 UDC 551.515.72:551.513.2(73)“1968.12” THEWEATHER ANDCIRCULATION OF DECEMBER 1968 Strong Blocking Over the Western Hemisphere and Cold in the United States RAYMOND A. GREEN Extended Forecast Division, Weather Bureau, ESSA, Suitland, Md. 1. MEAN CIRCULATION also increased inCanada and persisted over Greenland Blocking inthe WesternHemisphere, which had and Scandinavia, resulting in a band of positive height decreased in November, came back strongly in December. anomalies from the western Pacific across Canada to The most anomalous blocking feature of the December northernRussia (fig. 2). South of the positive zone, circulation was the strong ridge over the Aleutian Islands height departures were negative from the eastern Pacific (fig. 1) which replaced the deepBering Sea Low of across theUnited States and from the Atlantic to the November (Stark, 1969)’.resulting in anomalous 700-mb eastern Mediterranean. Although November’s deep Sibe- height changes betweenmonths of more than 200 m. rian Low shifted to the Arctic Ocean at itsoriginalintensity, Meanwhile, the mid-Pacific trough of November moved negativeheight anomalies predominatedthrough De- eastward and intensified at lower latitudes, the ridge in cember in Siberia. the Rockies decreased, andthe mid-United States In response to blocking, the axis of maximum 700-mb troughbroadened eastward intothe Atlantic. Blocking westerlies for the month (fig. 3) was south of normal over FIGURE1.-Mean 700-mb contours (decameters) for December 1968. Unauthenticated | Downloaded 10/02/21 09:23 AM UTC 282 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Vol. 97,No. 3 FIGURE 3.-Mean 700-mbwind speed (meters per second) for FIGURE2.-Departure from normal of mean 700-mb height (dec- December ,1968. -

Administrative Report for the Year Ending 30 June 1968 (To 15 May 1968)

RESTRICTED INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC FISHERIES II ICNAF Comm.Doc.68/8 Serial No.2059 (A.b.l7) ANNUAL MEETING - JUNE 1968 Administrative Report for the Year ending 30 June 1968 (to 15 May 1968) 1. The Commission's Officers Chairman of Commission Mr V.M.Kamentsev (USSR) Vice-Chairman of Commission Dr A.W.H.Needler (Canada) Chairman of Panel 1 Mr O. Lund (Norway) Chairman of Panel 2 Mr W.e.Tame (UK) (to September 1967) Chairman of Panel 3 Dr F. Chrzan (Poland) Chairman of Panel 4 Captain T. de Almeida (Portugal) Chairman of Panel 5 Mr T.A.Fulham (USA) Chairman of Panel A (Seals) Dr A.W.H.Needler (Canada) These officers, with one exception, were elected at the 1967 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of two years. Dr A.W.H.Needler was elected Chairman of Panel A at the 1966 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of two years. Chairman of Standing Committee on Research and Statistics Nr Sv. Aa. Horsted (Denmark) Chairman of Standing Committee on Finance and Administration Mr R. Green (USA) Chairman of Standing Committee on Regulatory Measures Mr J. Graham (UK) The Chairmen of Research and Statistics and Finance and Administration were elected at the 1967 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of one year. The Chairman of the Standing Committee on Regulatory Measures was elected at the first meeting of the Committee, 30 January 1968. 2. Panel Memberships for 1967/68 (cf. ICNAF Camm.Doc.68fl) Panel .1 l. 1. .!!. .2. ! Total Canada + + + + + 5 Denmark + + 2 France + + + + 4 Germany + + 2 Iceland + 1 Italy + + 2 Norway + + 2 Poland + + + 3 Portugal + + + + 4 Romania + 1 Spain + + + + 4 USSR + + + + + 5 UK + + + 3 USA ;. -

April 1968: Dr. Benjamin Mays E. Delivers Final Eulogy for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr

April 1968: Dr. Benjamin Mays E. delivers final eulogy for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, then recently retired as president of Morehouse College, delivers the final eulogy for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at Morehouse on April 9, 1968. Photograph courtesy of Baylor University. Benjamin Mays and the Rev. Martin Luther King promised each other: He who outlived the other would deliver his friend’s last eulogy. On April 9, 1968, Mays made good on the promise. After funeral services at Ebenezer Baptist Church, King’s mahogany coffin was born to Morehouse College on a rickety farm wagon pulled by two mules. There, Mays, the school’s 70-year-old president emeritus, delivered a final eulogy that also renounced what many saw coming: a turn toward violence for the black movement. King was “more courageous than those who advocate violence as a way out,” Mays told the estimated 150,000 mourners. “Martin Luther faced the dogs, the police, jail, heavy criticism, and finally death; and he never carried a gun, not even a knife to defend himself. He had only his faith in a just God to rely on.” Indeed, King’s assassination by James Earl Ray left many questioning the future of nonviolent protest in the late 1960s. Quoted in Time magazine a week after King’s funeral, Floyd McKissick, chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, offered this sober judgment: “The way things are today, not even Christ could come back and preach nonviolence.” Photo taken by photographer Flip Schulke on April 9, 1968 at Morehouse College.