Strawberry Flats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jain Karma Book (JAINA Education Series 251 – Level 2, 3Rd Edition (Aug 2020))

Jain Karma Book (JAINA Education Series 251 – Level 2, 3rd Edition (Aug 2020)) Compiled by Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington Referenced from materials produced by JAINA Education Committee Federation of Jain Associations of North America JAIN KARMA BOOK 2 Jain Karma Book - JES 251 (JAINA Education Series 251 - Level 2) Third Edition: August 2020 This book has No Copyright for private, personal, and non-commercial use only Please use the religious material respectfully and for nonprofit purposes. JSMW Acknowledgements We want to first thank our parents for making a continuous effort to bring Jain principles into our lives and solidifying the value of being a Jain. It is because of their guidance that we are living a Jain way of life today. We want to thank the Jain Centers across North America that have created a community environment for Jain followers. These centers have volunteers pouring countless hours for their community thus creating a forum for parents, seniors, young adults, and children to gather and unite with a shared goal of spiritual upliftment. We want to thank the Pathshala students of Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington who gave us the inspiration to make this book. Their willingness to learn and grow provided us the motivation to create an age friendly book on a very important and foundational Jain topic. Lastly, a personal thank you to Pravin Shah of Raleigh, NC. Uncle had a vision to provide Jain education to all who wish to receive it and his vision is flourishing from generation to generation. We are grateful for Pravin Uncle’s vision, his support during the creation of this book, and for him spending numerous hours in reviewing this book and providing feedback. -

Diez Datos Para Recordar a Marie Fredriksson, La Voz De Roxette Que Se Apaga

Diez datos para recordar a Marie Fredriksson, la voz de Roxette que se apaga El reciente fallecimiento de la cantante sueca y voz del dúo Roxette, Marie Fredriksson, impacta especialmente de lleno en la generación “sub 50” que entre 1989 y 1995 disfruta de la avalancha de hits que la banda regala al mundo. Su atractiva voz y su clásico pelo corto constituyen parte de su impronta personal, con la que colabora a la creación de verdaderos temas clásicos como “The Look”, “Joyride” y “Dangerous”, entre muchos otros. Aunque, sin duda, su mayor característica se encuentra en el valor con el que encara la lucha contra el cáncer (tumor cerebral), enfermedad con la que logra lidiar durante casi dos décadas. Su compañero de ruta en la reconocida banda pop, el multi-instrumentista Per Gessle, deja claro su afecto por la cantante y compositora en un comunicado: «No hace tanto que pasábamos días y noches en mi pequeño apartamento de Halmstad, escuchando música que nos encantaba, compartiendo sueños imposibles. ¡Y qué sueño fantástico llegamos a compartir! Gracias, Marie, gracias por todo. Fuiste una música realmente única, una cantante de un nivel que quizá no volvamos a experimentar. Pintaste mis canciones en blanco y negro con los colores más maravillosos». Como sencillo homenaje, compartimos un pequeño decálogo que permite hacerse de una idea general en torno a Fredriksson, una voz que forma parte de la banda sonora en la vida de millones de personas. 1.- El nombre completo de Marie es Gun-Marie Fredriksson y nace en la localidad sueca de Ossjo, el 30 de mayo de 1958. -

ROXETTE Aflyser Alt !

2016-04-18 17:20 CEST ROXETTE aflyser alt ! Roxette were supposed to start the last leg of their massive RoXXXette 30th Anniversary Tour on June 3rd. However, singer Marie Fredriksson has been advised by her doctorsto refrain from touring and as a consequence all the summer shows are cancelled. Their last performance was to be at the Grand Arena in Cape Town, South Africa on February 8 earlier this year. Marie Fredriksson:”It’s been an amazing 30 years! I feel nothing but joy and happiness when I look back ontheRoxette world tours. All our showsand memories over the years will forever be a big part of my life. I’m particularly proud and grateful for coming back in 2009 after my severe illness and to have been able to take Roxette around the globe a couple of more times. Sadly, now my touring days are over and I want to take this opportunity to thank our wonderful fans that has followed us on our long and winding journey. I look forward to the release of our album ”Good Karma” in June – for me it’s our best album ever!” Per Gessle: Who would have thought this small town band from the Swedish west coast wereto be still on the looseafter 30 years! We’ve done mind-blowing gigs all over the world that has taken us far beyond our wildest and craziest dreams. I want to thank all our fellow musicians and collaborators on and off the road. Thanks also to our beautiful fans, all of you who have listened, encouraged, waited, travelled, all of you who have shared the singing, laughter, joy and tears. -

Download the File “Tackforalltmariebytdr.Pdf”

Käraste Micke med barn, Tillsammans med er sörjer vi en underbar persons hädangång, och medan ni har förlorat en hustru och en mamma har miljoner av beundrare världen över förlorat en vän och en inspirationskälla. Många av dessa kände att de hade velat prata med er, dela sina historier om Marie med er, om vad hon betydde för dem, och hur mycket hon har förändrat deras liv. Det ni håller i era händer är en samling av över 6200 berättelser, funderingar och minnen från människor ni förmodligen inte kän- ner personligen, men som Marie har gjort ett enormt intryck på. Ni kommer att hitta både sorgliga och glada inlägg förstås, men huvuddelen av dem visar faktiskt hur enormt mycket bättre världen har blivit med hjälp av er, och vår, Marie. Hon kommer att leva kvar i så många människors hjärtan, och hon kommer aldrig att glömmas. Tack för allt Marie, The Daily Roxette å tusentals beundrares vägnar. A A. Sarper Erokay from Ankara/ Türkiye: How beautiful your heart was, how beautiful your songs were. It is beyond the words to describe my sorrow, yet it was pleasant to share life on world with you in the same time frame. Many of Roxette songs inspired me through life, so many memories both sad and pleasant. May angels brighten your way through joining the universe, rest in peace. Roxette music will echo forever wihtin the hearts, world and in eternity. And you’ll be remembered! A.Frank from Germany: Liebe Marie, dein Tod hat mich zu tiefst traurig gemacht. Ich werde deine Musik immer wieder hören. -

Insights Into Karma

INSIGHTS INTO KARMA Also by Alexander Peck and co-authored with Eva Peck: Pathway to Life – Through the Holy Scriptures Journey to the Divine Within – Through Silence, Stillness and Simplicity Let's Talk Anew – Modern Conversation Themes in English [ESL book] For more information on Alexander Peck, see these websites at: www.spirituality-for-life.org www.prayer-of-the-heart.org www.pathway-publishing.org 2 INSIGHTS INTO KARMA The Law of Cause and Effect Alexander Peck 3 The right of Alexander Peck to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. © Alexander Peck, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means except for the quotation of brief passages for the purpose of private study, research, or review. Cover design: Eva Peck Cover photo purchased from www.dreamstime.com Photo credits: Jindrich Degen Cover picture: The wagon wheel alludes to the Buddhist Wheel of Life. Karma is a law that influences all of life, expressed in the words "what goes around, comes around". Quotations for section divider pages are taken from: Mascaró, Juan, trans. The Dhammapada: The Path of Perfection. London: Penguin Books, 1973. They are intended to reflect the cause-effect theme underlying the book. This book was produced using the Blurb creative publishing service. It can be purchased online through: www.pathway -publishing.org Pathway Publishing Brisbane, Australia 4 This book is dedicated to You, the reader. May it be a cause for your personal Enlightenment. -

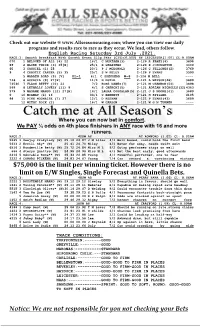

Website @ Where You Can View Our Daily Programs and Results Race to Race As They Occur

Check out our website @ www.Allseasonsracing.com; where you can view our daily programs and results race to race as they occur. We lead, others follow. English Racing Saturday 3rd July ,2021. RACE:1: Smooth Breakfast With Gareth Evans Sllg Stks (Cl5)£6,500) 6f LEICESTER[1:00] CL:8.00AM 070 1 BELOVED OF ALL (6) 22 16/1 C MURTAGH(3) 2-126 R FAHEY(6) 3898 89 2 BLINK TWICE (3) 35[B] 25/1 E GREATREX 2-126 E J-HOUGHTON 3400 60 3 CASSIEL (1) 25 20/1 P J MCDONALD 2-126 C FELLOWES(2) 3769 9 4 CHAOTIC CARTER (5) 35 25/1 S W KELLY 2-126 P EVANS 3390 5 WARREN ROAD (9) [V] PL-1 6/1 C SHEPHERD W-6 2-126 M BELL ---- 746 6 ACCACIA (8) 27[P] 11/4 H DOYLE 2-121 A WATSON(46) 3689 74540 7 FLASH BETTY (10) 22 7/2 ROSE DAWES(7) 2-121 M CHANNON(54) 3898 569 8 LETHALLY LOVELY (11) 9 4/1 S CHERCHI(5) 2-121 ADRIAN NICHOLLS(32)4363 579 9 MADAME MANGO (12) 27[H] 14/1 LAURA COUGHLAN(5) 2-121 J S MOORE(41) 3689 0 10 MIAMAY (4) 16 33/1 C BENNETT 2-121 H SPILLER 4105 98 11 PINK MOONRISE (7) 27 12/1 D KEENAN 2-121 P EVANS(43) 3689 12 WITHY ROCK (2) 16/1 W CARSON 2-121 W G M TURNER ---- Where you can now bet in comfort. We PAY ¼ odds on 4th place finishers in ANY race with 16 and more runners. -

Abecední KOMPLETNÍ SEZNAM HUDBY a MLUVENÉHO SLOVA - Do 1

abecední KOMPLETNÍ SEZNAM HUDBY A MLUVENÉHO SLOVA - do 1. pol. 2018 32743 CD 1975 I like it when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so2015 unaware of it / 25795 CD (Hed) Planet Earth The best of 2006 27813 CD 10,000 Maniacs Our time in Eden 1992 20981 CD 10,000 Maniacs The wishing chair 1985 30174 CD 100°C Brant rock 2008 23819 CD 100°C Evergreen 2004 27836 CD 10cc Bloody tourists 1978 29213 CD 10cc Sheet music 2000 25740 CD 12 Stones 12 Stones 2002 28482 CD -123 min. Dream 2009 22108 CD -123 min. Home 2002 24338 CD -123 min. Mom 2005 21160 CD -123 min. Shooba dooba 1999 21515 CD -123 min. Try 2001 29214 CD 2 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic sounds of The 13th Floor Elevators 2010 28616 CD 16 Horsepower Folklore 2002 26441 CD 2 Unlimited The Hits 2006 31106 CD 30 Seconds to Mars Love lust faith and dreams 2013 31107 CD 30 Seconds to Mars This is war 2009 32670 CD 4 Non Blondes Bigger, better, faster, more! / 1992 23750 CD 4TET 1st 2004 25313 CD 4TET 2nd 2005 26813 CD 4TET 3rd 2008 32436 CD 4TET 4th / 2016 31873 CD 5 Seconds of Summer 5 Seconds of Summer 2014 25959 CD 50 Cent Curtis 2007 23335 CD 50 Cent Get rich or die tryin' 2003 24826 CD 50 Cent The Massacre 2005 29454 CD 5th Dimension The age of aquarius 1969 29451 CD 808 State 808:88:98-10 years of 808 State 1998 25960 CD A bude hůř Basket 2001 33131 CD Aaronovitch, Ben Měsíc nad Soho / 2017 32419 CD Aaronovitch, Ben Řeky Londýna / 2016 20430 CD ABBA Gold 1992 20361 CD ABBA More ABBA Gold 1993 26814 CD V ABBA The albums 2008 32461 CD Abbott, Rachel Zabij mě znovu / 2016 24546 -

Ancient India

Ancient India 5.2 – Origins of Hinduism Essential Question: How do India’s rich history and culture affect the world today? Big Idea: Hinduism, the largest religion in India today, developed out of ancient Indian beliefs and practices. Key Word Definition Memory Clue Aryan/Indian social divisions similar to other social hierarchies varnas Brahmins - priests Kshatriyas – rulers/warriors Vaisyas – farmers, traders, craftspeople Sudras – laborers, non-Aryans When the varnas became further divided, the result caste system was more groups, or castes. The caste system divided Indian society into groups based on a person’s birth, wealth, or occupation. A group within Indian society that did not belong to untouchables any caste. They could only hold certain, often unpleasant jobs. sutras The guides that listed the rules for the caste system Aryan religion was based on the four Vedas, which are religious writings containing sacred hymns & poems. Vedas The oldest is the Rigveda, which includes hymns of praise to many gods. Hinduism The largest religion in India today, based on the blending of the Vedas, Vedic texts, and other religious ideas from different cultures Some important Hindu beliefs include polytheism, reincarnation, and karma. atman This is the Hindu word for soul. It should be reunited with Brahman, the universal spirit. Key Word Definition Memory Clue The process of rebirth where a soul is born and reincarnation reborn into different physical forms until it can see through the illusion of life and reach salvation The effects that good or bad actions have on a person’s soul - Evil actions cause bad karma, which results in being karma reborn into a lower caste in a person’s next life. -

Bootleg: the Secret History of the Other Recording Industry

BOOTLEG The Secret History of the Other Recording Industry CLINTON HEYLIN St. Martin's Press New York m To sweet D. Welcome to the machine BOOTLEG. Copyright © 1994 by Clinton Heylin. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. ISBN 0-312-13031-7 First published in Great Britain by the Penguin Group First Edition: June 1995 10 987654321 Contents Prologue i Introduction: A Boot by Any Other Name ... 5 Artifacts 1 Prehistory: From the Bard to the Blues 15 2 The Custodians of Vocal History 27 3 The First Great White Wonders 41 4 All Rights Reserved, All Wrongs Reversed 71 5 The Smokin' Pig 91 6 Going Underground 105 7 Vicki's Vinyl 129 8 White Cover Folks! 143 9 Anarchy in the UK 163 10 East/West 179 11 Real Cuts at Last 209 12 Complete Control 229 Audiophiles 13 Eraserhead Can Rub You Out 251 14 It Was More Than Twenty Years Ago . 265 15 Some Ultra Rare Sweet Apple Trax 277 16 They Said it Couldn't be Done 291 17 It Was Less Than Twenty Years Ago . 309 18 The Third Generation 319 19 The First Rays of the New Rising Sun 333 20 The Status Quo Re-established 343 21 The House That Apple Built 363 22 Bringing it All Back Home 371 Aesthetics 23 One Man's Boxed-Set (Is Another Man's Bootleg) 381 24 Roll Your Tapes, Bootleggers 391 25 Copycats Ripped Off My Songs 403 Glossary 415 The Top 100 Bootlegs 417 Bibliography 420 Notes 424 Index 429 Acknowledgements 442 Prologue In the summer of 1969, in a small cluster of independent LA record stores, there appeared a white-labelled two-disc set housed in a plain cardboard sleeve, with just three letters hand-stamped on the cover - GWW. -

Friedkin Nontinated As New Revelle Provost

Friedkin Nontinated As times New Revelle Provost UNIVERSITY Of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Chancellor's office Friedkln, a professor of bnng them (~ tudent~ and has announced the biology, was described by faculty member~ ) togethN f'I"mination of Biology Saltman to the San Diego In a relationship that goe~ professor Morris Friedkin as Union as a " humanist who beyond the large lecture provost of Revelle College, . also happens to do hall," he said subject to the approval of science" He told the Triton the UC regents . Times that he feels Friedkl n Fnedkln cam to UCSD In Friedkin would replace will " move effectively and 1969 from the Tufts Dr. Muarry Goodman, who well" in nonscience UniverSity School of filled the post temporarily disciplines Medicine, where he served when Vice-chancellor Paul The nominee said he for a time as head of the Saltman left Revelle to take hopes to stab ilize the biology d partmcnt He ha~ his present position. enrollment of Revelle, also taught at the medical The Revelle Provost commenting that expansion school at Wa shington Search Committee, a at UCSD would be better at University. student-f<\culty group, Third and Fourth Co lleges. He received Bachelor's originally nominated Dr. " I think the major problem and Master's degrees from June' Tap, a professor of at any university today is Iowa I).tate University, psychology at the the detrimental effect of a obtaining a doctorate In University of Minnesota. large student body and a biochemistry from the Tap declined the small facu lty I'd like to University of Chicago nomination for family reasons . -

Good Karma Café Grand Opening Ceremonies Feb. 3

February 2014 Published Since November 1968 Only Good News For 46 Years VOLUME 46 NO. 2 Good Karma Café grand opening ceremonies Feb. 3 By Doug Kates How many times have you sat at the East Activity Center swimming pool and thought, “I wish there was somewhere I could go to get a cold water?” Or how many times have you fin- ished a set of tennis and wished there was somewhere you could go in the community for a snack? Starting Feb. 3, both of these wishes will come true, along with even more possibilities. The Good Karma Café will of- ficially open for business at 10 a.m., Monday, Feb. 3. The entrance will be located in the lower level of the EAC, where the library used to be located. The café will be a source for hot and cold beverages, lunch items, pre- packaged dinners, and fresh and healthy snacks, seven days a week. “I have received many positive comments,” said SCA Manager Dessa Barabba. “People are excited. They can’t wait for the café to open. There is a lot of interest in the take-home items.” For the first five days the café is open, anyone making a purchase will be given a raffle ticket for daily draw- Last month, On Top of the World announced a new café coming to the community. On Feb. 3, resi- ings. You need not be present to win, dents are invited to the East Activity Center to see the new café. Pictured above are the temporary but must stop by the café and make a walls put up during construction. -

14 Questions People Ask About Hinduism and 14 Tweetable Answers

14 Questions People Ask About Hinduism …and 14 tweetable answers! pieter weltevrede Cow Worship, Cremation, Caste, Many Gods, Karma, Reincarnation, Idols, Yoga & More Humanity’s most profound faith is now a global phenomenon. Students, teachers, Why does Hinduism have so many Gods? neighbors and friends are full of questions. Misconceptions run rampant. Here are fourteen thoughtful answers you can use to set the record straight. Hindus all believe in one Supreme God who created the universe. He is all-pervasive. He created many Gods, ave you ever been put on the spot with a provocative people have asked me about my tradition. I don’t know everything, highly advanced spiritual beings, to be His helpers. question about Hinduism, even one that really shouldn’t be but I will try to answer your question.” 3) “First, you should know 1 so hard to answer? If so, you are not alone. It takes some that in Hinduism, it is not only belief and intellectual understanding good preparation and a little attitude adjustment to confi- that is important. Hindus place the greatest value on experiencing Hdently field queries on your faith—be they from friendly co-workers, each of these truths personally.” 4) The fourth type of prologue is students, passersby or especially from Christian evangelists. Back to repeat the question to see if the person has actually stated what in the spring of 1990, a group of teens from the Hindu Temple of he wants to know. Repeat the question in your own words and ask if ontrary to prevailing the natural universe and noth- Greater Chicago, Lemont, sent a request to Hinduism Today for “of- you have understood his query correctly.