The Application of Precision Measurement in Historic Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy Edited by John Makeham, Australian National University VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/mcp. The Discovery of Chinese Logic By Joachim Kurtz LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kurtz, Joachim. The discovery of Chinese logic / by Joachim Kurtz. p. cm. — (Modern Chinese philosophy, ISSN 1875-9386 ; v. 1) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17338-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Logic—China—History. I. Title. II. Series. BC39.5.C47K87 2011 160.951—dc23 2011018902 ISSN 1875-9386 ISBN 978 90 04 17338 5 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................. -

Dengfeng Observatory, China

90 ICOMOS–IAU Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage Archaeological/historical/heritage research: The Taosi site was first discovered in the 1950s. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, archaeologists excavated nine chiefly tombs with rich grave goods, together with large numbers of common burials and dwelling foundations. Archaeologists first discovered the walled towns of the Early and Middle Periods in 1999. The remains of the observatory were first discovered in 2003 and totally uncovered in 2004. Archaeoastronomical surveys were undertaken in 2005. This work has been published in a variety of Chinese journals. Chinese archaeoastronomers and archaeologists are currently conducting further collaborative research at Taosi Observatory, sponsored jointly by the Committee of Natural Science of China and the Academy of Science of China. The project, which is due to finish in 2011, has purchased the right to occupy the main field of the observatory site for two years. Main threats or potential threats to the sites: The most critical potential threat to the observatory site itself is from the burials of native villagers, which are placed randomly. The skyline formed by Taer Hill, which is a crucial part of the visual landscape since it contains the sunrise points, is potentially threatened by mining, which could cause the collapse of parts of the top of the hill. The government of Xiangfen County is currently trying to shut down some of the mines, but it is unclear whether a ban on mining could be policed effectively in the longer term. Management, interpretation and outreach: The county government is trying to purchase the land from the local farmers in order to carry out a conservation project as soon as possible. -

Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’S New Year’S Eve Celebrations

Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge Suggested citation: Frew, E. & Mair. J. (2014). Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations. In Frost, W. & Laing, J. (Eds) Rituals and traditional events in the modern world. Routledge Hogmanay Rituals: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations Elspeth A. Frew La Trobe University Judith Mair Department of Management Monash University ABSTRACT Hogmanay, which is the name given to New Year’s Eve in Scotland, is a long-standing festival with roots going far back into pagan times. However, such festivals are losing their traditions and are becoming almost generic public celebrations devoid of the original rites and rituals that originally made them unique. Using the framework of Falassi’s (1987) festival rites and rituals, this chapter utilises a duoethnographic approach to examine Hogmanay traditions in contemporary Scotland and the extent to which these have been transferred to another country. The chapter reflects on the traditions which have survived and those that have been consigned to history. Hogmanay and Paganism: Scotland’s New Year’s Eve Celebrations INTRODUCTION New Year’s Eve (or Hogmanay as it is known in Scotland) is celebrated in many countries around the world, and often takes the form of a public celebration with fireworks, music and a carnival atmosphere. However, Hogmanay itself is a long-standing festival in Scotland with roots going far back into pagan times. Some of the rites and rituals associated with Hogmanay are centuries old, and the tradition of celebrating New Year Eve (as Hogmanay) on a grander scale than Christmas has been a part of Scottish life for many hundreds of years. -

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Sunrise and Sunset Azimuths in the Planning of Ancient Chinese Towns. International Journal of Sciences, Alkhaer, UK, 2013, 2 (11), pp.52-59. 10.18483/ijSci.334. hal- 02264434 HAL Id: hal-02264434 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02264434 Submitted on 8 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, Italy Abstract: In the planning of some Chinese towns we can see an evident orientation with the cardinal direction north-south. However, other features reveal a possible orientation with the directions of sunrise and sunset on solstices too, as in the case of Shangdu (Xanadu), the summer capital of Kublai Khan. Here we discuss some other examples of a possible solar orientation in the planning of ancient towns. We will analyse the plans of Xi’an, Khanbalik and Dali. Keywords: Satellite Imagery, Orientation, Archaeoastronomy, China 1. Introduction different from a solar orientation with sunrise and Recently we have discussed a possible solar sunset directions. -

Sarah Provancher Jeanne Hilt (502) 439-7138 (502) 614-4122 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Tuesday, June 5, 2018 CONTACT: Sarah Provancher Jeanne Hilt (502) 439-7138 (502) 614-4122 [email protected] [email protected] DOWNTOWN TO SHOWCASE FÊTE DE LA MUSIQUE LOUISVILLE ON JUNE 21 ST Downtown Louisville to celebrate the Summer Solstice with live music and more than 30 street performers for a day-long celebration of French culture Louisville, KY – A little taste of France is coming to Downtown Louisville on the summer solstice, Thursday, June 21st, with Fête de la Musique Louisville (pronounced fet de la myzic). The event, which means “celebration of music” in French, has been taking place in Paris on the summer solstice since 1982. Downtown Louisville’s “celebration of music” is presented by Alliance Francaise de Louisville in conjunction with the Louisville Downtown Partnership (LDP). Music will literally fill the downtown streets all day on the 21st with dozens of free live performances over the lunchtime hour and during a special Happy Hour showcase on the front steps of the Kentucky Center from 5:30-7:30pm. A list of performance venues with scheduled performers from 11am-1pm are: Fourth Street Live! – Classical musicians including The NouLou Chamber Players, 90.5 WUOL Young Musicians and Harin Oh, GFA Youth Guitar Summit Kindred Plaza – Hewn From The Mountain, a local Irish band 400 W. Market Plaza – FrenchAxe, a French band from Cincinnati Old Forester Distillery – A local jug band The salsa band Milenio is the scheduled performance group for the Happy Hour also at Fourth Street Live! from 5 – 7 pm. "In Paris and throughout France, the Fête de la Musique is literally 24 hours filled with music by all types of musicians of all skill levels. -

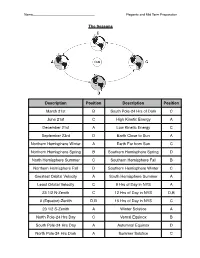

Regents and Midterm Prep Answers

Name__________________________________!Regents and Mid Term Preparation The Seasons Description Position Description Position March 21st B South Pole-24 Hrs of Dark C June 21st C High Kinetic Energy A December 21st A Low Kinetic Energy C September 23rd D Earth Close to Sun A Northern Hemisphere Winter A Earth Far from Sun C Northern Hemisphere Spring B Southern Hemisphere Spring D North Hemisphere Summer C Southern Hemisphere Fall B Northern Hemisphere Fall D Southern Hemisphere Winter C Greatest Orbital Velocity A South Hemisphere Summer A Least Orbital Velocity C 9 Hrs of Day in NYS A 23 1/2 N-Zenith C 12 Hrs of Day in NYS D,B 0 (Equator)-Zenith D,B 15 Hrs of Day in NYS C 23 1/2 S-Zenith A Winter Solstice A North Pole-24 Hrs Day C Vernal Equinox B South Pole-24 Hrs Day A Autumnal Equinox D North Pole-24 Hrs Dark A Summer Solstice C Name__________________________________!Regents and Mid Term Preparation Sunʼs Path in NYS 1. What direction does the sun rise in summer? _____NE___________________ 2. What direction does the sun rise in winter? _________SE_________________ 3. What direction does the sun rise in fall/spring? ________E_______________ 4. How long is the sun out in fall/spring? ____12________ 5. How long is the sun out in winter? _________9______ 6. How long is the sun out in summer? ________15_______ 7. What direction do you look to see the noon time sun? _____S________ 8. What direction do you look to see polaris? _______N_________ 9. From sunrise to noon, what happens to the length of a shadow? ___SMALLER___ 10. -

Summer Solstice

A FREE RESOURCE PACK FROM EDMENTUM Summer Solstice PreK–6th Topical Teaching Grade Range Resources Free school resources by Edmentum. This may be reproduced for class use. Summer Solstice Topical Teaching Resources What Does This Pack Include? This pack has been created by teachers, for teachers. In it you’ll find high quality teaching resources to help your students understand the background of Summer Solstice and why the days feel longer in the summer. To go directly to the content, simply click on the title in the index below: FACT SHEETS: Pre-K – Grade 3 Grades 3-6 Grades 3-6 Discover why the Sun rises earlier in the day Understand how Earth moves and how it Discover how other countries celebrate and sets later every night. revolves around the Sun. Summer Solstice. CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS: Pre-K – Grade 2 Grades 3-6 Discuss what shadows are and how you can create them. Discuss how Earth’s tilt cause the seasons to change. ACTIVITY SHEETS AND ANSWERS: Pre-K – Grade 3 Grades 3-6 Students are to work in pairs to explain what happens during Follow the directions to create a diagram that describes the Summer Solstice. Summer Solstice. POSTER: Pre-K – Grade 6 Enjoyed these resources? Learn more about how Edmentum can support your elementary students! Email us at www.edmentum.com or call us on 800.447.5286 Summer Solstice Fact Sheet • Have you ever noticed in the summer that the days feel longer? This is because there are more hours of daylight in the summer. • In the summer, the Sun rises earlier in the day and sets later every night. -

Vestiges of Midsummer Ritual in Motets for John the Baptist

Early Music History (2011) Volume 30. Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0261127911000027 M A A Email: [email protected] FIRE, FOLIAGE AND FURY: VESTIGES OF MIDSUMMER RITUAL IN MOTETS FOR JOHN THE BAPTIST The thirteenth-century motet repertory has been understood on a wide spectrum, with recent scholarship amplifying the relationship between the liturgical tenors and the commentary in the upper voices. This study examines a family of motets based on the tenors IOHANNE and MULIERUM from the feast of the Nativity of John the Baptist (24 June). Several texts within this motet family make references to well-known traditions associated with the pagan festival of Midsummer, the celebration of the summer solstice. Allusions to popular solstitial practices including the lighting of bonfires and the public criticism of authority, in addition to the cultural awareness of the sun’s power on this day, conspicuously surface in these motets, particularly when viewed through the lens of the tenor. The study suggests the further obfuscation of sacred and secular poles in the motet through attentiveness to images of popular, pre-Christian rituals that survive in these polyphonic works. In the northern French village of Jumièges from the late Middle Ages to the middle of the nineteenth century, a peculiar fraternal ritual took place. Each year on the evening of the twenty-third of June, the Brotherhood of the Green Wolf chose its new chief. Arrayed in a brimless green hat in the shape of a cone, the elected master led the men to a priest and choir; Portions of this study were read at the Medieval and Renaissance Conference at the Institut für Musikwissenschaft, University of Vienna, 8–11 August 2007 and at the University of Chicago’s Medieval Workshop on 19 May 2006. -

Guo Shoujing (Chine, 1989)

T OPTICIENS CÉLÈBRES OPTICIENS CÉLÈBRES Principales dates PORTRAI 1231 – Naissance à Xingtai (actuelle province de Hebei, Chine) 1280 Etablit le Calendrier Shoushi 1286 Nommé Directeur du Bureau de l’astronomie et du calendrier 1290 Rénove et aménage le Gand Canal de Dadu 1292 Nommé Gouverneur du Bureau des travaux hydrauliques 1316 – Décès à Dadu (actuelle Pékin, Chine) Pièce de 5 Yuans à l’efgie de Guo Shoujing (Chine, 1989). Guo Shoujing (ou Kuo Shou-ching) Riad Haidar, [email protected] Grand astronome, ingénieur hydraulique astucieux et mathématicien inspiré, contemporain de Marco Polo à la cour de Kubilai Khan sous la dynastie Yuan, Guo Shoujing est une des grandes gures des sciences chinoises. Surnommé le Tycho Brahe de la Chine, on lui doit plusieurs instruments d’astronomie (dont le perfectionnement du gnomon1 antique) et surtout d’avoir établi le fameux calendrier Shoushi, si précis qu’il servit de référence pendant près de quatre siècles en Asie et que de nombreux historiens le considèrent comme le précurseur du calendrier Grégorien. uo Shoujing naît en 1231 dans une famille modeste de C’est à cette époque que Kubilai, petit-ls du grand conquérant la ville de Xingtai, dans l’actuelle province de Hebei à mongol Genghis Khan, entreprend son ascension du pouvoir su- G l’Est de la Chine (hebei signie littéralement au nord du prême chinois. Il est nommé Grand Khan le 5 mai 1260 et, en euve Jaune). Son grand-père paternel Yong est un érudit, fameux souverain éclairé, commence à organiser l’empire en appliquant à travers la Chine pour sa maîtrise parfaite des Cinq Classiques les méthodes qui ont fait leur preuve lors de ses précédentes ad- qui forment le socle culturel commun depuis Confucius, ainsi que ministrations et qui lui permettront de bâtir un des empires les plus pour sa connaissance des mathématiques et de l’hydraulique. -

Celebrating Winter Solstice 2020

Celebrating Winter Solstice 2020 December 21- 5:02 am EST Interesting & Fun Facts for the Longest Night of the Year More Daylight Hours to Come! Celebrating Winter Solstice Shab-e-Yalda (Yalda Night) is one of the most ancient Persian festivals annually celebrated on winter solstice by Iranians all around the world. Yalda is a winter solstice celebration; it is the last night of autumn and the longest night of the year. Yalda means birth and it refers to the birth of Mitra; the mythological goddess of light. Since days get longer and nights to get shorter in winter, Iranians celebrate the last night of autumn as the renewal of the sun and the victory of light over darkness. To pass the longest night of the year, it is common to eat nuts and fruits, read poetry, make good wishes to give a warm welcome to winter. Earth - Sun Position During Winter Solstice In the Northern Hemisphere, the Winter Solstice is the shortest day of the year. During Winter Solstice, the Northern Hemisphere is the most inclined away from Jupiter and Saturn Will Form Rare the Sun. After the solstice, which falls on "Christmas Star" on Winter Solstice December 21 or 22 every year, the days On December 21, 2020 Jupiter and Saturn begin to lengthen. Probably because the day marks the beginning of the return of the will appear closer in Earth’s night sky than Sun, many cultures celebrate a holiday near they have since 1226 A.D. Winter Solstice, including Christmas, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa. Position of the Sun and Earth During Seasonal Changes View of Solstice from Space Information prepared by Dr. -

Eclipses and the Victory of European Astronomy in China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine (EASTM - Universität Tübingen) EASTM 27 (2007): 127-145 Eclipses and the Victory of European Astronomy in China Lü Lingfeng [Lü Lingfeng is associate professor at Department of History of Science and Archaeometry, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). He re- ceived his Ph.D. from USTC in 2002. He was Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellow at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg from December 2004 to November 2006.] * * * In the late Ming dynasty, European astronomy was introduced into China by the Jesuits. After a long period of competition with traditional Chinese astronomy, it finally came to dominate imperial astronomy in the early Qing dynasty. Accord- ing to historical documents, the most important factor in the success of European astronomy in China was its exactitude in the calculation of celestial phenomena, especially solar and lunar eclipses, which not only played a very special role in traditional Chinese political astrology but belonged among the most important celestial events for judging the precision of a system of calendrical astronomy. 1 This was true in ancient China from the Eastern Han (25-220) period all the way up to the late Ming period (1368-1644). During the calendar-debate between European, Islamic and Chinese astronomy in the Chongzhen reign period (1628- 1644), Xu Guangqi 徐 光 啟 (1562-1633) 2 also pointed out: “The erroneousness and exactness of a calendrical system can obviously only be seen from eclipses, while other phenomena are all too shady and dull to serve as indication.” 3 Re- cently, Shi Yunli and I have made a systematic analysis of the degree of precision of both the calculation and the observation of luni-solar eclipses in the late Ming 1 The astronomer Liu Hong 劉 洪 of the Eastern Han dynasty pointed out that eclipse prediction was an important way to check the accuracy of a calendar. -

Earth-Moon-Sun-System EQUINOX Presentation V2.Pdf

The Sun http://c.tadst.com/gfx/750x500/sunrise.jpg?1 The sun dominates activity on Earth: living and nonliving. It'd be hard to imagine a day without it. The daily pattern of the sun rising in the East and setting in the West is how we measure time...marking off the days of our lives. 6 The Sun http://c.tadst.com/gfx/750x500/sunrise.jpg?1 Virtually all life on Earth is aware of, and responds to, the sun's movements. Well before there was written history, humankind had studied those patterns. 7 Daily Patterns of the Sun • The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. • The time between sunrises is always the same: that amount of time is called a "day," which we divide into 24 hours. Note: The term "day" can be confusing since it is used in two ways: • The time between sunrises (always 24 hours). • To contrast "day" to "night," in which case day means the time during which there is daylight (varies in length). For instance, when we refer to the summer solstice as being the longest day of the year, we mean that it has the most daylight hours of any day. 8 Explaining the Sun What would be the simplest explanation of these two patterns? • The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. • The time between sunrises is always the same: that amount of time is called a "day." We now divide the day into 24 hours. Discuss some ideas to explain these patterns.