Is Local Ecological Knowledge a Useful Conservation Tool for Small Mammals in a Caribbean Multicultural Landscape? ⇑ Samuel T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla De Mona, P.R. by Ángel M

In Search of the Extinct Hutia in Cave Deposits of Isla de Mona, P.R. by Ángel M. Nieves-Rivera, M.S. and Donald A. McFarlane, Ph.D. Isolobodon portoricensis, the extinct have been domesticated, and its abundant (14C) date was obtained on charcoal and Puerto Rican hutia (a large guinea-pig like remains in kitchen middens indicate that it bone fragments from Cueva Negra, rodent), was about the size of the surviving formed part of the diet for the early settlers associated with hutia bones (Frank, 1998). Hispaniolan hutia Plagiodontia (Rodentia: (Nowak, 1991; Flemming and MacPhee, This analysis yielded an uncorrected 14C age Capromydae). Isolobodon portoricensis was 1999). This species of hutia was extinct, of 380 ±60 before present, and a corrected originally reported from Cueva Ceiba (next apparently shortly after the coming of calendar age of 1525 AD, (1 sigma range to Utuado, P.R.) in 1916 by J. A. Allen (1916), European explorers, according to most 1480-1655 AD). This date coincides with the and it is known today only by skeletal remains historians. final occupation of Isla de Mona by the Taino from Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Haiti, The first person to take an interest in the Indians (1578 AD; Wadsworth 1977). The Île de la Gonâve, ÎIe de la Tortue), Puerto faunal remains of the caves of Isla de Mona purpose of this article is to report some new Rico (mainland, Isla de Mona, Caja de was mammalogist Harold E. Anthony, who paleontological discoveries of the Puerto Muertos, Vieques), the Virgin Islands (St. in 1926 collected the first Puerto Rican hutia Rican hutia in cave deposits of Isla de Mona Croix, St. -

Ecologia De Les Illes

Observations on the habitat and ecology of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) in the Dominican Republic Jose A. OTTENWALDER Proyecto Biodiversidad GEF-PNUD/ONAPLAN. Programa de las Naciones para el Desarrollo (PNUD) y Oficina Nacional de Planificacion. Apartado 1424, Mirador Sur. Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana Ottenwalder, J.A. 1999. Observations on the habitat and ecology of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) in the Dominican Republic. Mon. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears, 6 I Mon. Inst. Est. Bal. 66: 123-168. ISBN: 84- 87026-86-9. Palma de Mallorca. The habitat of the Hispaniolan Solenodon (Solenodon paradoxus) was investiga ted in the Dominican Republic in relation to particular environmental parameters (geomorphology, geologicalstructure, soil type, elevation, life zone, vegetation, rainfall, and temperature). Results are discussed in relation to relevant species environment interactions, particularly habitat preferences and life history patterns of the species. Comparisons on the habitat, ecology and life history are made bet ween S. paradoxus and the Cuban Solenodon (S. cubanus), the only other living member of the genus. Keywords: Solenodon, Caribbean, Antilles, Ecology, Conservation Biology. Observaciones sobre el habitat y ecologia del Solenodon de la Hispaniola (Solenodon paradox us) en la Republica Dominicana. EI habitat del Solenodon de la Hispaniola (Solenodon paradoxus) fue estudiado en la Republica Dominicana en relacion a una serie de parametres ambientales (geomorfologia, estructura geologica, tipo de suelo, elevacion, zona de vida, for macion vegetal, precipitacion, y temperatura). Las relaciones especie-habitat son analizadas usando un modelo empirico descriptivo. Las observaciones sobre inte racciones especie-rnedio ambiente resultantes son discutidas particularmente en relacion a preferencias aparentes de habitat y a los patrones de historia natural de la especie. -

Investigating Evolutionary Processes Using Ancient and Historical DNA of Rodent Species

Investigating evolutionary processes using ancient and historical DNA of rodent species Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of London Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX Selina Brace November 2010 1 Declaration I, Selina Brace, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, it is always clearly stated. Selina Brace Ian Barnes 2 “Why should we look to the past? ……Because there is nowhere else to look.” James Burke 3 Abstract The Late Quaternary has been a period of significant change for terrestrial mammals, including episodes of extinction, population sub-division and colonisation. Studying this period provides a means to improve understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, and to determine processes that have led to current distributions. For large mammals, recent work has demonstrated the utility of ancient DNA in understanding demographic change and phylogenetic relationships, largely through well-preserved specimens from permafrost and deep cave deposits. In contrast, much less ancient DNA work has been conducted on small mammals. This project focuses on the development of ancient mitochondrial DNA datasets to explore the utility of rodent ancient DNA analysis. Two studies in Europe investigate population change over millennial timescales. Arctic collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) specimens are chronologically sampled from a single cave locality, Trou Al’Wesse (Belgian Ardennes). Two end Pleistocene population extinction-recolonisation events are identified and correspond temporally with - localised disappearance of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). A second study examines postglacial histories of European water voles (Arvicola), revealing two temporally distinct colonisation events in the UK. -

Solenodon Genome Reveals Convergent Evolution of Venom in Eulipotyphlan Mammals

Solenodon genome reveals convergent evolution of venom in eulipotyphlan mammals Nicholas R. Casewella,1, Daniel Petrasb,c, Daren C. Cardd,e,f, Vivek Suranseg, Alexis M. Mychajliwh,i,j, David Richardsk,l, Ivan Koludarovm, Laura-Oana Albulescua, Julien Slagboomn, Benjamin-Florian Hempelb, Neville M. Ngumk, Rosalind J. Kennerleyo, Jorge L. Broccap, Gareth Whiteleya, Robert A. Harrisona, Fiona M. S. Boltona, Jordan Debonoq, Freek J. Vonkr, Jessica Alföldis, Jeremy Johnsons, Elinor K. Karlssons,t, Kerstin Lindblad-Tohs,u, Ian R. Mellork, Roderich D. Süssmuthb, Bryan G. Fryq, Sanjaya Kuruppuv,w, Wayne C. Hodgsonv, Jeroen Kooln, Todd A. Castoed, Ian Barnesx, Kartik Sunagarg, Eivind A. B. Undheimy,z,aa, and Samuel T. Turveybb aCentre for Snakebite Research & Interventions, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, L3 5QA Liverpool, United Kingdom; bInstitut für Chemie, Technische Universität Berlin, 10623 Berlin, Germany; cCollaborative Mass Spectrometry Innovation Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; dDepartment of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76010; eDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; fMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; gEvolutionary Venomics Lab, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, 560012 Bangalore, India; hDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; iDepartment of Rancho La Brea, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, -

The Last Survivors: Current Status and Conservation of the Non-Volant Land

1 The Last Survivors: current status and conservation of the non-volant land 2 mammals of the insular Caribbean 3 4 SAMUEL T. TURVEY,* ROSALIND J. KENNERLEY, JOSE M. NUÑEZ-MIÑO, AND RICHARD P. 5 YOUNG 6 7 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London NW1 4RY (STT) 8 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Les Augrès Manor, Trinity, Jersey JE3 5BP, Channel 9 Islands (RJK, JNM, RPY) 10 11 *Correspondent: [email protected] 12 13 Running header: Status of Caribbean land mammals 14 1 15 The insular Caribbean is among the few oceanic-type island systems colonized by non-volant 16 land mammals. This region also has experienced the world’s highest levels of historical 17 mammal extinctions, with at least 29 species lost since AD 1500. Representatives of only 2 18 land-mammal families (Capromyidae and Solenodontidae) now survive, in Cuba, Hispaniola, 19 Jamaica, and the Bahama Archipelago. The conservation status of Caribbean land mammals 20 is surprisingly poorly understood. The most recent IUCN Red List assessment, from 2008, 21 recognized 15 endemic species, of which 13 were assessed as threatened. We reassessed all 22 available baseline data on the current status of the Caribbean land-mammal fauna within the 23 framework of the IUCN Red List, to determine specific conservation requirements for 24 Caribbean land-mammal species using an evidence-based approach. We recognize only 13 25 surviving species, 1 of which is not formally described and cannot be assessed using IUCN 26 criteria; 3 further species previously considered valid are interpreted as junior synonyms or 27 subspecies. -

The Behavior of Solenodon Paradoxus in Captivity with Comments on the Behavior of Other Insectivora

The Behavior of Solenodon paradoxus in Captivity with Comments on the Behavior of Other Insectivora JOHN F. EISENBERG1 Department of Zoology, University of Maryland & EDWIN GOULD2 Department of Mental Hygiene, Laboratory of Comparative Behavior, Johns Hopkins University (Plates I & II) I. INTRODUCTION For comparative purposes the authors utilized Solenodon paradoxus, confined to the island the extensive collection of living tenrecs main- of Hispaniola, and S. cubanus, endemic to Cuba, tained by Dr. Gould at Johns Hopkins Uni- versity, and drew upon their previous behavioral comprise the sole living members of the family studies of insectivores, which have already been Solenodontidae. A full-grown specimen of S. published in part elsewhere (Eisenberg, 1964; paradoxus may weigh up to 1 kgm. and attain a Gould, 1964, 1965). head and body length of 300 mm. Although large size and primitive molar cusp pattern have led II. SPECIMENS AND MAINTENANCE taxonomists to include this genus with the tenrecs Four specimens of Solenodon paradoxus (one of Madagascar, further morphological studies male, three females) were purchased from a have led certain workers to conclude that Sol- dealer in the Dominican Republic. The male enodon is a primitive soricoid more closely allied (M) and one female (J) were immature and, to the shrews than to the zalambdadont tenrecs extrapolating from their weights (Mohr, 1936 (McDowell, 1958). II), were judged to be four and six months old, The behavior of S. paradoxus was reviewed respectively. The juveniles were studied as a by Dr. Erna Mohr (1936-38). Since her series of pair by Dr. Eisenberg. In addition, all four ani- papers, however, much more has been learned mals were employed in two-animal encounters concerning the behavior of not only the soleno- and were recorded during studies of vocal com- don but also the insectivores of the families munication. -

Deciduous Forest

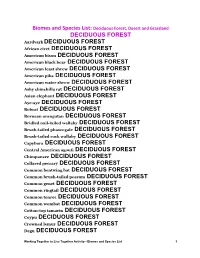

Biomes and Species List: Deciduous Forest, Desert and Grassland DECIDUOUS FOREST Aardvark DECIDUOUS FOREST African civet DECIDUOUS FOREST American bison DECIDUOUS FOREST American black bear DECIDUOUS FOREST American least shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST American pika DECIDUOUS FOREST American water shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST Ashy chinchilla rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Asian elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Aye-aye DECIDUOUS FOREST Bobcat DECIDUOUS FOREST Bornean orangutan DECIDUOUS FOREST Bridled nail-tailed wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed phascogale DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed rock wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Capybara DECIDUOUS FOREST Central American agouti DECIDUOUS FOREST Chimpanzee DECIDUOUS FOREST Collared peccary DECIDUOUS FOREST Common bentwing bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Common brush-tailed possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Common genet DECIDUOUS FOREST Common ringtail DECIDUOUS FOREST Common tenrec DECIDUOUS FOREST Common wombat DECIDUOUS FOREST Cotton-top tamarin DECIDUOUS FOREST Coypu DECIDUOUS FOREST Crowned lemur DECIDUOUS FOREST Degu DECIDUOUS FOREST Working Together to Live Together Activity—Biomes and Species List 1 Desert cottontail DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern chipmunk DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern gray kangaroo DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern mole DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern pygmy possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Edible dormouse DECIDUOUS FOREST Ermine DECIDUOUS FOREST Eurasian wild pig DECIDUOUS FOREST European badger DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest hog DECIDUOUS FOREST Funnel-eared bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Gambian rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Geoffroy's spider monkey -

Mitogenomic Sequences Support a North–South Subspecies Subdivision Within Solenodon Paradoxus

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Faculty Creative and Scholarly Works 4-20-2016 Mitogenomic sequences support a north–south subspecies subdivision within Solenodon paradoxus Adam L. Brandt Kirill Grigorev Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández Liz A. Paullino William J. Murphy See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/faculty_staff_works Authors Adam L. Brandt, Kirill Grigorev, Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández, Liz A. Paullino, William J. Murphy, Adrell Núñez, Aleksey Komissarov, Jessica R. Brandt, Pavel Dobrynin, David Hernández-Martich, Roberto María, Stephen J. O'Brien, Luis E. Rodríguez, Juan C. Martínez-Cruzado, Taras K. Oleksyk, and Alfred L. Roca This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group in Mitochondrial DNA Part A on 15/03/2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/24701394.2016.1167891. 1 Mitochondrial DNA, Original Article 2 3 4 Title: Mitogenomic sequences support a north-south subspecies subdivision within 5 Solenodon paradoxus 6 7 8 Authors: Adam L. Brandt1,2+, Kirill Grigorev4+, Yashira M. Afanador-Hernández4, Liz A. 9 Paulino5, William J. Murphy6, Adrell Núñez7, Aleksey Komissarov8, Jessica R. Brandt1, 10 Pavel Dobrynin8, J. David Hernández-Martich9, Roberto María7, Stephen J. O’Brien8,10, 11 Luis E. Rodríguez5, Juan C. Martínez-Cruzado4, Taras K. Oleksyk4* and Alfred L. 12 Roca1,2,3* 13 14 +Equal contributors 15 *Corresponding authors: [email protected]; [email protected] 16 17 18 Affiliations: 1Department -

Alexis Museum Loan NM

STANFORD UNIVERSITY STANFORD, CALIFORNIA 94305-5020 DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY PH. 650.725.2655 371 Serrra Mall FAX 650.723.0589 http://www.stanford.edu/group/hadlylab/ [email protected] 4/26/13 Joseph A. Cook Division of Mammals The Museum of Southwestern Biology at the University of New Mexico Dear Joe: I am writing on behalf of my graduate student, Alexis Mychajliw and her collaborator, Nat Clarke, to request the sampling of museum specimens (tissue, skins, skeletons) for DNA extraction for use in our study on the evolution of venom genes within Eulipotyphlan mammals. Please find included in this request the catalogue numbers of the desired specimens, as well as a summary of the project in which they will be used. We have prioritized the use of frozen or ethanol preserved tissues to avoid the destruction of museum skins, and seek tissue samples from other museums if only skins are available for a species at MSB. The Hadly lab has extensive experience in the non-destructive sampling of specimens for genetic analyses. Thank you for your consideration and assistance with our research. Please contact Alexis ([email protected]) with any questions or concerns regarding our project or sampling protocols, or for any additional information necessary for your decision and the processing of this request. Alexis is a first-year student in my laboratory at Stanford and her project outline is attached. As we are located at Stanford University, we are unable to personally pick up loan materials from the MSB. We request that you ship materials to us in ethanol or buffer. -

Solenodon Genome Reveals Convergent Evolution of Venom in Eulipotyphlan Mammals

Solenodon genome reveals convergent evolution of venom in eulipotyphlan mammals Nicholas R. Casewella,1, Daniel Petrasb,c, Daren C. Cardd,e,f, Vivek Suranseg, Alexis M. Mychajliwh,i,j, David Richardsk,l, Ivan Koludarovm, Laura-Oana Albulescua, Julien Slagboomn, Benjamin-Florian Hempelb, Neville M. Ngumk, Rosalind J. Kennerleyo, Jorge L. Broccap, Gareth Whiteleya, Robert A. Harrisona, Fiona M. S. Boltona, Jordan Debonoq, Freek J. Vonkr, Jessica Alföldis, Jeremy Johnsons, Elinor K. Karlssons,t, Kerstin Lindblad-Tohs,u, Ian R. Mellork, Roderich D. Süssmuthb, Bryan G. Fryq, Sanjaya Kuruppuv,w, Wayne C. Hodgsonv, Jeroen Kooln, Todd A. Castoed, Ian Barnesx, Kartik Sunagarg, Eivind A. B. Undheimy,z,aa, and Samuel T. Turveybb aCentre for Snakebite Research & Interventions, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place, L3 5QA Liverpool, United Kingdom; bInstitut für Chemie, Technische Universität Berlin, 10623 Berlin, Germany; cCollaborative Mass Spectrometry Innovation Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; dDepartment of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76010; eDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; fMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; gEvolutionary Venomics Lab, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, 560012 Bangalore, India; hDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305; iDepartment of Rancho La Brea, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, -

World Wildlife Fund Mint Sets BEAUTIFUL POSTAGE STAMPS from AROUND the WORLD F-VF, NH OR BETTER

World Wildlife Fund Mint Sets BEAUTIFUL POSTAGE STAMPS FROM AROUND THE WORLD F-VF, NH OR BETTER Stamps are all Fine to Very Fine or Better, Never Hinged Please order by country name and Scott #. Where there isn’t a Scott #, please give description AFGHANISTAN Scott # Year & Description Retail Price 1172-75 1985 Leopard (4) ........................................................... 10.75 .. 1998 Steppe Sheep Se-tenant Strip of 4 .......................... 11.00 .. same, Se-tenant Sheet of 16 .......................................... 44.00 .. 2004 Himalayan Musk Deer (4)........................................ 13.00 .. same, Se-tenant Vertical Strip of 4 .................................. 13.50 .. same, Se-tenant Sheet of 16 .......................................... 53.50 AITUTAKI 533-36 2002 Tahitian Blue Lorikeet (4) ........................................ 7.25 533-36 same, 4 Mini-Sheets of 4................................................ 28.75 ALBANIA 2332-35 1990 Chamois Se-tenant Block of 4.................................. 8.50 ALGERIA 872-75 1988 Barbary Macaque (4).............................................. 8.00 ANGOLA 781-84 1990 Sable Antelope Se-tenant Block of 4 ....................... 10.00 1058 1999 Lesser Flamingo Se-tenant Strip of 4........................ 7.00 1058 same, Se-tenant Sheet of 16 .......................................... 27.50 1279 2004 Black & White Colobus, Se-tenant Block of 4............. 6.00 1279 same, Se-tenant Horizontal Strip of 4............................... 6.00 1279 same, Se-tenant Sheet -

Talpid Mole Phylogeny Unites Shrew Moles and Illuminates Overlooked Cryptic Species Diversity Kai He,‡,†,1,2 Akio Shinohara,†,3 Kristofer M

Talpid Mole Phylogeny Unites Shrew Moles and Illuminates Overlooked Cryptic Species Diversity Kai He,‡,†,1,2 Akio Shinohara,†,3 Kristofer M. Helgen,4 Mark S. Springer,5 Xue-Long Jiang,*,1 and Kevin L. Campbell*,2 1State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MN , Canada 3Department of Bio-resources, Division of Biotechnology, Frontier Science Research Center, University of Miyazaki, Miyazaki, Japan 4National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 5Department of Biology, University of California, Riverside, CA ‡Present address: The Kyoto University Museum, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan †These authors contributed equally to this work. *Corresponding authors: E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Associate editor: Emma Teeling Abstract The mammalian family Talpidae (moles, shrew moles, desmans) is characterized by diverse ecomorphologies associated with terrestrial, semi-aquatic, semi-fossorial, fossorial, and aquatic-fossorial lifestyles. Prominent specializations involved with these different lifestyles, and the transitions between them, pose outstanding questions regarding the evolutionary history within the family, not only for living but also for fossil taxa. Here, we investigate the phylogenetic relationships, divergence times, and biogeographic history of the family using 19 nuclear and 2 mitochondrial genes (16 kb) from 60% of described species representing all 17 genera. Our phylogenetic analyses help settle classical questions in the evolution of moles, identify an ancient (mid-Miocene) split within the monotypic genus Scaptonyx, and indicate that talpid species richness may be nearly 30% higher than previously recognized. Our results also uniformly support the monophyly of long-tailed moles with the two shrew mole tribes and confirm that the Gansu mole is the sole living Asian member of an otherwise North American radiation.