A CASE STUDY of CANARY WHARF, LONDON by Ara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 King's Arms Yard

1 KING’S ARMS YARD LONDON EC2 The Amundi Collection INVESTMENT SUMMARY 1 King’s Arms Yard is a core City of London office investment. Grade A office building situated within 50 metres of the Bank of England. 100% prime City of London location. 56,071 sq ft of high quality office and ancillary accommodation over basement, lower ground, ground and six upper floors. Rolfe Judd designed scheme, completed in 2009 with a BREEAM Very Good rating. Prominent corner site with excellent natural daylight from three elevations and stunning views over the Bank of England. Held long leasehold for a term expiring in 2141 with a current head rent payable of £5,000 per annum. The property is securely let to eight tenants at a current gross passing rent of £2,763,197 per annum reflecting a below market rent of only £49.28 per sq ft overall. The WAULT is approximately 3.1 years to expiries. Offers are invited in excess of £58,300,000, subject to contract and exclusive of VAT, for our client’s long leasehold interest in 1 King’s Arms Yard. This represents an attractive net initial yield of 4.65% and a capital value of £1,040 per sq ft, assuming acquisition costs of 1.80% through the purchase of the Luxembourg SARL. 1 King’s Arms Yard – London 100 BISHOPSGATE TOWER 42 22 BISHOPSGATE LEADENHALL BUILDING THE LLOYD’S BUILDING LOCATION BROADGATE LIVERPOOL STREET FINSBURY CIRCUS 1 KING’S ARMS YARD LONDON EC2 MOORGATE BANK BANK OF ENGLAND ROYAL EXCHANGE 1 King’s Arms Yard – London LOCATION 1 King’s Arms Yard occupies a prime corner site on King’s Arms Yard and Tokenhouse Yard of approximately 0.24 acres. -

Broadgate, Ec2 Industrial-Style, Contemporary Workspace Where Shoreditch Meets the City

BROADWALK HOUSE BROADGATE, EC2 INDUSTRIAL-STYLE, CONTEMPORARY WORKSPACE WHERE SHOREDITCH MEETS THE CITY Broadwalk House offers flexible office space, reimagined by transformation specialist architects Barr Gazetas in 2020. Level 3 (16,663 sq ft) benefits from a brand new ‘plug & play’ finish and is ready for immediate occupation. An additional 3,563 sq ft of flexible workspace is available on the ground floor. Room for 190+ people with the option of extra space New dramatic reception Vibrant and stimulating environment New cycle racks, showers and lockers Built-in cabled workstations ready to plug in, sit down and work WiredScore Gold BROADGATE: WHERE INNOVATION OLD STREET AND FINANCE PLAY OLD STREET STREET Built around 4.5 acres of public squares, Broadgate is the largest pedestrianised OLD neighbourhood in central London and the meeting ground of Europe’s capitals of investment and tech. It is a public arena for new food, retail and culture, and comes alive with a year-round programme of over 100 events. Its outstanding amenities include everything from GREAT EASTERN STREET world-class dining to the latest in sports and wellness facilities. ROAD CITY CONNECTIVITY Liverpool Street Station plus Moorgate and Shoreditch High Street provide access to five tube lines; London overground; national trains; buses and Crossrail (opening 2019). D A O SHOREDITCH HIGH STREET N R Farringdon 2 mins URTAI C Canary Wharf 6 mins Bond Street 7 mins COMMERCIAL STREET Stratford 8 mins WORSHIP STREET WORSHI P STREET GATE L Paddington O 9 mins F King’s Cross -

Application Form, Form Our Agreement with You

Valu-Trac Administration Services Additional Investor Information Document VT Tcam Investment Funds VT Tcam Absolute Return Portfolio VT Tcam Growth Portfolio VT Tcam Income Portfolio Authorised Corporate Director: Valu-Trac Investment Management Limited Orton Fochabers Moray Scotland IV32 7QE Investment Manager: Tcam Asset Management Limited Level 1 Princes Exchange 1 Earl Grey Street Edinburgh EH3 9BN Tel: +44 (0)131 297 3767 Fax: +44 (0)131 297 3769 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tcam.com Depositary: National Westminster Bank Plc _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Valu-Trac Administration Services is a division of Valu-Trac Investment Management Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority Orton, Moray Level 13, Broadgate Tower Scotland, IV32 7QE 20 Primrose Street Tel: +44(0)1343 880344 London Fax: +44(0)1343 880267 EC2A 2EW Valu-Trac Administration Services Valu-Trac Investment Management Limited (‘VT’) is authorised and +44(0) 1343 880344, fax to +44(0) 1343 880267 or by email to regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, Register No. 145168. [email protected]. Your complaint will be fully investigated and a full Further information may be obtained from the Financial Services register resolution sought. A copy of our complaints policy is available upon by visiting the FCA website at https://register.fca.org.uk/, by telephoning request. 0800 111 6768 or by writing to the FCA at 25 The North Colonnade, Canary Wharf, London E14 5HS. When we have considered your complaint we will issue you with our final response letter. If you are not satisfied with our response, or if we Please read the Additional Investor Information including the Terms and cannot issue a final response letter within eight weeks of receipt of your Conditions carefully. -

Culture Mile Look and Feel Strategy

CULTURE MILE LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY DETAILED DELIVERY PLAN 1 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 05 • The team • Structure of this document • Public and Stakeholder engagement THE AIMS 01 - Form a Culture Spine 17 02 - Take the Inside Out 35 03 - Discover and Explore 51 04 - Be Recognisable and be Different 69 SUMMARY DELIVERY PLAN 81 APPENDIX 87 • Appendix 1 - Form a Culture Spine • Appendix 2 - Take the Inside Out • Appendix 3 - Discover and Explore • Appendix 4 - Be Recognisable and be Different 3 4 CULTURE MILE LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY INTRODUCTION 5 THE TEAM FLUID As lead consultant we are responsible for the project management, leadership and vision development. Fluid led on the site analysis, research, engagement and development of the public realm strategy. LEAD CONSULTANT ALAN BAXTER VISION DEVELOPMENT Provided heritage expertise and input into the transport, PUBLIC REALM STRATEGY movement and access strategies. CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY (CAS) Developed the cultural strategies that aid place activation and advised on governance considerations. SEAM Looked at the opportunities for lighting to aid wayfinding, highlight landmarks and give expression to key spaces. ARUP DIGITAL PUBLIC INFORMATION HERITAGE Developed digital tools for interactive communications CULTURAL STRATEGY LIGHTING STRATEGY LANDSCAPE AND GREENING TRANSPORT AND MOVEMENT and public information. SECURITY ARUP LANDSCAPE Developed the landscape, green infrastructure and sustainability principles and advised on management. ARUP SECURITY Advised on security matters, providing guidance on protecting people and property in the public realm. 6 STRUCTURE OF THIS DOCUMENT LOOK AND FEEL STRATEGY This document is organised into four sections: 1. PUBLIC AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT - Contains information on findings of engagement about Culture Mile and the Look and Feel Strategy. -

2-3 Finsbury Avenue, Broadgate in the City of London Planning Application No: 16/00149/FULEIA

planning report D&P/3763/02 4 September 2017 2-3 Finsbury Avenue, Broadgate in the City of London planning application no: 16/00149/FULEIA Strategic planning application stage II referral Town & Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended); Greater London Authority Acts 1999 and 2007; Town & Country Planning (Mayor of London) Order 2008. The proposal Demolition of existing buildings and construction of a part 36, part 20, part 13, part 8 storey building (maximum 168.4m AOD) to provide office accommodation; flexible retail uses; cafe/restaurant; events space and a publicly accessible roof terrace and associated landscaping (total floor area 85,378sq.m. GEA). The applicant The applicant is Bluebutton Properties Ltd and the architect is Arup Associates. Key dates Stage 1 report: 21 April 2016 Committee meeting: 4 October 2017 Strategic issues summary Principle of development. Proposed uplift in office floorspace supported in CAZ; contribution to affordable housing and affordable workspace secured; free-of-charge public access to roof terrace secured. (paras 8-11) Design: Amendments to proposals have addressed Stage 1 issues. (paras 12-18) Climate change: Energy issues addressed; carbon off-set contribution secured. (para 19) Transport: Further information and amendments have addressed Stage 1 issues on cycle parking provision, and conditions and section 106 obligations secured. (paras 20-22) The Council’s decision The City of London Corporation has resolved to grant permission, subject to conditions and a section 106 legal agreement. Recommendation That the City of London Corporation be advised that the Mayor is content for it to determine the case itself, subject to any action that the Secretary of State may take, and does not therefore wish to direct refusal or direct that he is to be the local planning authority. -

Hidden Cities: Reinventing the Non-Space Between Street and Subway

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Jae Min Lee University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Jae Min, "Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2984. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Abstract The connections leading to underground transit lines have not received the attention given to public spaces above ground. Considered to be merely infrastructure, the design and planning of these underground passageways has been dominated by engineering and capital investment principles, with little attention to place-making. This underground transportation area, often dismissed as “non-space,” is a by-product of high-density transit-oriented development, and becomes increasingly valuable and complex as cities become larger and denser. This dissertation explores the design of five of these hidden cities where there has been a serious effort to make them into desirable public spaces. Over thirty-two million urbanites navigate these underground labyrinths in New York City, Hong Kong, London, Moscow, and Paris every day. These in-between spaces have evolved from simple stairwells to networked corridors, to transit concourses, to transit malls, and to the financial engines for affordable public transit. -

Download the Art

CONSTANCE DE JONG • Speaking of the River JAY BATTLE • Vanishing Point PUBLIC ART AT 1. 2000 • Audio benches 5. 1999 • Derbyshire stone, steel CANARY WHARF O • CANARY RIVERSIDE Speaking of the River O • CANARY RIVERSIDE Vanishing Point was sponsored by Canary Wharf Group but This map identifies the works of art purchased, commissioned or looks a little like the shell of a mythical sea was part of a wider project commissioned creature that has perhaps been washed loaned by Canary Wharf Group, which include stand-alone pieces by Public Art Development Trust, which up from the Thames. The stone has been and integrated artist architectural works. The works are numbered linked the river Thames in London with the polished to reveal the natural, lined core. sequentially as to their location on the estate from west to east, river Hudson in New York. De Jong created a Having trained as a stone mason in Canada, and the text indicates whether they are sited inside ‘I’ with blue gentle, evocative sound-scape using recorded Battle came to England to study stone numbering, or outside ‘O’ with orange numbering. interviews and stories that relate the human carving and in 1997 became Head Carver experience of both these locations, told by at Salisbury Cathedral, contributing to Artists and key to works on map: people for whom the river is a daily presence. its constant restoration works as well as Bob Allen 1 6 Giusseppe Lund 3 Two audio benches are located 100m apart on running his own studio where he creates Ron Arad 2 Michael Lyons 51 54 the riverside promenade. -

The Collaborative City

the londoncollaborative The Collaborative City Working together to shape London’s future March 2008 THE PROJECT The London Collaborative aims to increase the capacity of London’s public sector to respond to the key strategic challenges facing the capital. These include meeting the needs of a growing, increasingly diverse and transient population; extending prosperity while safe- guarding cohesion and wellbeing, and preparing for change driven by carbon reduction. For more information visit young- foundation.org/london Abbey Wood Abchurch Lane Abchurch Yard Acton Acton Green Adams Court Addington Addiscombe Addle Hill Addle Street Adelphi Wharf Albion Place Aldborough Hatch Alder- manbury Aldermanbury Square Alderman’s Walk Alders- brook Aldersgate Street Aldersgate Street Aldgate Aldgate Aldgate High Street Alexandra Palace Alexandra Park Allhal- lows and Stairs Allhallows Lane Alperton Amen Corner Amen CornerThe Amen Collaborative Court America Square City Amerley Anchor Wharf Angel Working Angel Court together Angel to Court shape Angel London’s Passage future Angel Street Arkley Arthur Street Artillery Ground Artillery Lane Artillery AperfieldLane Artillery Apothecary Passage Street Arundel Appold Stairs StreetArundel Ardleigh Street Ashen Green- tree CourtFORE WAustinORD Friars Austin Friars Passage4 Austin Friars Square 1 AveINTRO MariaDUctio LaneN Avery Hill Axe Inn Back6 Alley Back of Golden2 Square OVerVie WBalham Ball Court Bandonhill 10 Bank Bankend Wharf Bankside3 LONDON to BarbicanDAY Barking Barkingside12 Barley Mow Passage4 -

CORPORATION of LONDON

Committee: Date: Item no. Planning and Transportation 3rd February 2015 Subject: Valid planning applications received by Department of the Built Environment Public 1. Pursuant to the instructions of your Committee, I attach for your information a list detailing development applications received by the Department of the Built Environment since my report to the last meeting. 2. Any questions of detail arising from these reports can be sent to [email protected]. DETAILS OF VALID APPLICATIONS Application Address Proposal Date of Number & Ward Validation 14/01006/FULMAJ Sugar Quay, Lower Variation of condition 53 (adherence 09/12/2014 Billingsgate Thames Street, to the approved plans) of planning London, EC3R permission reference no. 6EA, 12/01104/FULMAJ dated 16th September 2013 to make minor material amendments to the permitted scheme including lowering of the first floor soffit level and repositioning of the two north cores, rationalisation of restaurant deliveries and refuse collection, facade and landscaping improvements and associated works. 14/01216/FULL Dashwood House, The formation of an external seating 18/12/2014 Bishopsgate 69 Old Broad area with associated screening and Street, London, ramp and shopfront alterations EC2M 1QS including the installation of two awnings. 14/01254/FULL 133 Middlesex Extension at roof level [55sq.m GIA] 22/12/2014 Bishopsgate Street, London, E1 to provide an additional storey of 7JF accommodation (third floor). 14/01285/FULEIA 100 Liverpool Refurbishment and extension of 07/01/2015 Bishopsgate -

C257 LIS XSM10 Broadgate Utilities WB and Excavation Combined Report.Pdf

Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall Excavated Evaluation and GWBs, Fieldwork Report (XSM10) C257-MLA-T1-RGN-CRG03-50014 v2 Non-technical summary This report covers a summary of the results from archaeological fieldwork carried out by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) on the site of the future Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall, Liverpool Street, London EC2M, within the City of London. The site consists of the new utilities corridor and other utilities diversions within the Broadgate Ticket Hall construction worksite. The report was commissioned from MOLA by Crossrail Ltd. The phases of fieldwork covered in this report include the utilities corridor, sewer shafts MHS1 and MHS2-100 and the open cut sewer diversion. A sewer heading leading from MHS2-100 was undertaken as a general watching brief. This fieldwork follows the initial phase of archaeological evaluation in 2010–2011 (MOLA for Crossrail 2012, C257-MLA-X-RGN-CRG02-50064 [v2]) and 2011–2012 (MOLA for Crossrail 2012, C257-MLA-X-XCS-CRG02-50012 [v2]); the current report amalgamates these results in order to further inform the forthcoming excavation of the future ticket hall. Natural terrace gravels were reached in every trench, overlain by waterlain deposits of alluvial clay interspersed with occasional bands of gravel. These are thought to represent episodes of flooding from the Walbrook stream. The eastern edge of the stream itself was present at the western side of the site, running north–south. While a small group of redeposited struck flints was recovered during the fieldwork, there was no tangible evidence for prehistoric activity on the site itself. Evidence was found for several phases of Roman activity, dating to the early 2nd century AD, demonstrating water management in this area of the Walbrook valley. -

Project Sheet Broadgate.Ai

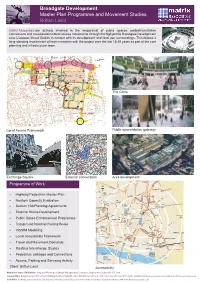

Broadgate Development Master Plan Programme and Movement Studies British Land Matrix Associates are actively involved in the reappraisal of public spaces, pedestrian/station connections and travel patterns/local access movements through the high profile Broadgate Development over Liverpool Street Station in context with its development and land use surroundings. This follows a long-standing involvement of team members with the project over the last 15-20 years as part of the core planning and infrastructure team. EXISTING RATIONALISE UPGRADE CROSSING TS EXISTING NEW 2 WAY ENTRY LAYOUT TS TS POLICE * * N * CORDON* POINT ATE BISHOPSG SHOREDITCH HIGH ST NORTON FOLGATE PROPOSED EXCHANGE ARCADE *TS CONGESTION T CHARGING E FUTURE 201 E POINT R BISHOPSGATE T T PROPOSED S TAXI * RAILTRACK NS ACCESS R * E DEVELOPMENT LIVERPOOL EAST EXCHANGE CONNECTION TO T PROPOSED HOUSE STREET A T PLATFORMS E RAIL E TAXIS E * T STATION NORTH- UNDERGROUND E GR SIGNAL ELIMINATE E R E GATE R T PEDESTRIAN BOX T MROS S EXCHANGE I HOUSE S ROUTE PEDESTRIAN P * PR SQUARE I * H SQUARE ELIMINATE BUS S * SUN ST PASSAGE STANDING R O * W * * *OLD BROAD ST CURTAIN ROAD NEW CLOSE OFF L STAIRS O AP PUBLIC O PO P LD R ST SPACE E * V I WORKS TO * L RELEASE REPLACE TS LIVERPOOL ST FRONTAGE WITH PRIORITY * CONTROL * * * The Circle BLO MF RATIONALISE IELD S JUNCTION* T ACE CROWN PL ST N O D L E SUN STREET WILSON STREET E POLICE CORDON H PLAC POINT GATEWAY OUT S * MOORGATE EXISTING TS Local Access Framework Public space/station gateway Exchange Square External connections Area development AD 1500m RO Y E N K Programme of Work C A CIT H N Y RO AD A RD COLUMBI TY GOSSET RD NI. -

01708550118 Trusted EC3 Billingsgate Emergency Walk In

01708550118 Trusted EC3 Billingsgate Emergency Walk In Cooker Install Specialists EC4 Broadgate EC2 Commercial Walk In Oven Repair Engineers EC1 Farringdon WC1 Covent Gardens WC2 Advantages for having commercial gas wok to do the cooking The main advantage of wok beyond its constructed material is its curved concave shape. The shape produces a small, hot area at the bottom which allows some of the food to be seared by intense heat while using relatively little fuel. The large sloped sides also make it easier for chefs to employ the tossing cooking technique on solid and thick liquid food with less spillage and a greater margin of safety. Curved sides also allows a person to cook without having to "chase the food around the pan" since bite-sized or finely chopped stir-fry ingredients usually tumble back to the center of the wok when agitated. The curve also provides a larger usable cooking surface versus western-styled pots and pans, which typically have vertical edges. This allows large pieces of food seared at the bottom of the wok to be pushed up the gently sloped sides to continue cooking at a slower rate. While this occurs another ingredient for the same dish needing high heat is being cooked at the bottom. The pointed bottom also allows even small amounts of oil to pool. As such, large food items can be shallow fried, while finely chopped garlic, hot peppers, green onions, and ginger can be essentially deep-fried in both cases with very small amount of cooking oil. We repair, maintain, service and install all commercial – domestic