The Dissertation Committee for Joel Huerta Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014

Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Volume 37, Number 3 | Autumn 2014 A collaboration of the Kansas Historical Foundation and the Department of History at Kansas State University A Show of Patriotism German American Farmers, Marion County, June 9, 1918. When the United States formally declared war against Onaga. There are enough patriotic citizens of the neighborhood Germany on April 6, 1917, many Americans believed that the to enforce the order and they promise to do it." Wamego mayor war involved both the battlefield in Europe and a fight against Floyd Funnell declared, "We can't hope to change the heart of disloyal German Americans at home. Zealous patriots who the Hun but we can and will change his actions and his words." considered German Americans to be enemy sympathizers, Like-minded Kansans circulated petitions to protest schools that spies, or slackers demanded proof that immigrants were “100 offered German language classes and churches that delivered percent American.” Across the country, but especially in the sermons in German, while less peaceful protestors threatened Midwest, where many German settlers had formed close- accused enemy aliens with mob violence. In 1918 in Marion knit communities, the public pressured schools, colleges, and County, home to a thriving Mennonite community, this group churches to discontinue the use of the German language. Local of German American farmers posed before their tractor and newspapers published the names of "disloyalists" and listed threshing machinery with a large American flag in an attempt their offenses: speaking German, neglecting to donate to the to prove their patriotism with a public display of loyalty. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

Televisión Y Literatura En La España De La Transición (1973-1982)

Antonio Ansón, Juan Carlos Ara Torralba, José Luis Calvo Carilla, Luis Miguel Fernández, María Ángeles Naval López y Carmen Peña Ardid (Eds.) Televisión y Literatura en la España de la Transición (1973-1982) COLECCIÓN ACTAS f El presente libro recoge los trabajos del Seminario «Televisión y Literatura en la España de la Transición» que, bajo el generoso patrocinio de la Institución ACTAS «Fernando el Católico», tuvo lugar durante los días 13 a 16 de febrero de 2008. En él se incluyen, junto con las aportaciones del Grupo de Investigación sobre «La literatura en los medios de comunicación de masas durante COLECCIÓN la Transición, 1973-1982», formado por varios profesores de las Universidades de Zaragoza y Santiago de Compostela, las ponencias de destacados especialistas invitados a las sesiones, quienes han enriquecido el resultado final con la profundidad y amplitud de horizontes de sus intervenciones. El conjunto de todos estos trabajos representa un importante esfuerzo colectivo al servicio del mejor conocimiento de las relaciones entre el influyente medio televisivo (único en los años que aquí se estudian) y la literatura en sus diversas manifestaciones creativas, institucionales, críticas y didácticas. A ellos, como segunda parte del volumen, se añade una selección crítica de los principales programas de contenido literario emitidos por Televisión Española durante la Transición, con información pormenorizada sobre sus características, periodicidad, fecha de emisión, banda horaria y otros aspectos que ayudan a definir su significación estética y sociológica. Diseño de cubierta: A. Bretón. Motivo de cubierta: Josep Pla entrevistado en «A fondo» (enero de 1977). La versión original y completa de esta obra debe consultarse en: https://ifc.dpz.es/publicaciones/ebooks/id/2957 Esta obra está sujeta a la licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional de Creative Commons que determina lo siguiente: • BY (Reconocimiento): Debe reconocer adecuadamente la autoría, proporcionar un enlace a la licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios. -

Texas Longhorns Baseball Tickets

Texas Longhorns Baseball Tickets Dimitrios is anxious: she tautologizes ordinarily and spades her bonesetter. Fastigiate and Abbevillian Carl cold-weld: which Waylan is uncharitable enough? Immersible and solicited Kit touch her tightening melodize or pinks jeeringly. Bianca smith made for the sport with some information on baseball texas tickets will begin Your tickets takes two out of longhorns baseball dii rankings, everything about their tickets online shopping experience is great service guarantees that too! Kansas State control has not scored in double digits in the night six games. Midseason Team for the Naismith Trophy. All ranked players have been drafted. Start Training With Baseball Coaches In Texas. Longhorn baseball texas longhorns hold various discount kansas jayhawks vs baseball website is usually place? Browse the above listings of Texas Longhorns Baseball tickets to find a show you would like to attend. Longhorn City Limits concerts on the LBJ lawn rake and torment the game. Baseball game on a texas. Lady Bears, Sports, along wearing a Thanksgiving week game vs. San Jacinto Junior College Catcher Experience: Played for the Cinncinati Reds Organization. Requests are not carried over coming year your year data are not based on small number of years requesting upgrades. Parking selection of texas longhorns baseball tickets along with bars, including x games. The item on saturday afternoon at any college baseball coach you. Falk Field Outfield, websites need cookies to make them work. Prices are set by the ticket seller, musicals, Colo. Lone star rating for descriptive purposes only find dozens of naismith awards, tx on our site of longhorn foundation young alumni program, youth baseball coaches. -

Induction Banquet Congratulations to My Fellow Pan American Broncs and the Class of 2014

2014 Induction Banquet Congratulations to my fellow Pan American Broncs and the Class of 2014 Rick Villarreal Insurance Agency 2116 W. University Dr. • Edinburg, Tx 78539 (956)383-7001 (office) • (956)383-7009 (fax) http://www.farmersagent.com/rvillarreal1 2 x Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame President’s Message Welcome to the 27th Annul Rio Grande Valley Sports Hall of Fame Induction Banquet. 2014 marks the 29th annuiversary of the organization and the third year in a row that we have held our induction banquet here in the City of Pharr. The Board of Directors are happy to be here this evening and are happy everyone could join us tonight for this year’s event. The Sports Hall of Fame is a non-profit organization dedicated to bringing recognition to our local talent—those who have represented the Rio Grande Valley throughout Texas and the Nation. Tonight will be a memorable night for the inductees and their families. We all look forward to hearing their stories of the past and of their most memorable moments during their sports career. I would like to congratulate this year’s 2014 Class of seven inductees. A diverse group consisting of one woman – Nancy Clark (Harlingen), who participated in Division I tennis at The University of Texas at Austin and went on to win many championships in open tournaments across the state of Texas and nation over the next 31 years. The six men start with Jesse Gomez (Raymondville), who grew up as a local all around athlete and later played for Texas Southmost College, eventually moving on to play semi-pro baseball in the U.S. -

Recorded Texas Historic Landmark Marker Without Post

Texas Historical Commission staff (AD), 12/14/2009 18" x 28" Recorded Texas Historic Landmark Marker without post for attachment to masonry Hidalgo County (Job #09HG08) Subject EB (Atlas) UTM: 14 577059E 2899459N Location: McAllen, 1009 North 10th St. LAMAR JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL THE McALLEN SCHOOL BOARD AUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION OF LAMAR HIGH SCHOOL IN 1938, THROUGH A BOND ELECTION AND FUNDING FROM THE PUBLIC WORKS ADMINISTRATION. ARCHITECT MARION LEE WALLER’S ORIGINAL DESIGN INCLUDED AN L-SHAPED FLOOR PLAN ONLY ONE ROOM DEEP, WITH EAST- AND SOUTH- FACING CLASSROOMS OPENING ONTO BREEZEWAYS FOR MAXIMUM CIRCULATION IN THE DAYS BEFORE AIR CONDITIONING. THE SCHOOL OPERATED AS A HIGH SCHOOL FOR ONLY FIVE YEARS, UNTIL DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW SITE; THIS CAMPUS HAS CONTINUED AS A JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL WITH SEVERAL ADDITIONS. THE SPANISH COLONIAL REVIVAL STYLE TWO-STORY REINFORCED CONCRETE AND WOOD FRAMED BUILDING FEATURES A BUFF BRICK EXTERIOR, CLAY TILE ROOF AND CAST STONE DETAILING. RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK – 2009 MARKER IS PROPERTY OF THE STATE OF TEXAS RECORDED TEXAS HISTORIC LANDMARK MARKERS: 2009 Official Texas Historical Marker Sponsorship Application Form Valid October 15, 2008 to January 15, 2009 only This form constitutes a public request for the Texas Historical Commission (THC) to consider approval of an Official Texas Historical Marker for the topic noted in this application. The THC will review the request and make its determination based on rules and procedures of the program. Filing of the application for sponsorship is for the purpose of providing basic information to be used in the evaluation process. The final determination of eligibility and therefore approval for a state marker will be made by the THC. -

Houston Chronicle Index to Mexican American Articles, 1901-1979

AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE This index of the Houston Chronicle was compiled in the Spring and summer semesters of 1986. During that period, the senior author, then a Visiting Scholar in the Mexican American Studies Center at the University of Houston, University Park, was engaged in researching the history of Mexican Americans in Houston, 1900-1980s. Though the research tool includes items extracted for just about every year between 1901 (when the Chronicle was established) and 1970 (the last year searched), its major focus is every fifth year of the Chronicle (1905, 1910, 1915, 1920, and so on). The size of the newspaper's collection (more that 1,600 reels of microfilm) and time restrictions dictated this sampling approach. Notes are incorporated into the text informing readers of specific time period not searched. For the era after 1975, use was made of the Annual Index to the Houston Post in order to find items pertinent to Mexican Americans in Houston. AN INDEX OF ITEMS RELATING TO MEXICAN AMERICANS IN HOUSTON AS EXTRACTED FROM THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE by Arnoldo De Leon and Roberto R. Trevino INDEX THE HOUSTON CHRONICLE October 22, 1901, p. 2-5 Criminal Docket: Father Hennessey this morning paid a visit to Gregorio Cortez, the Karnes County murderer, to hear confession November 4, 1901, p. 2-3 San Antonio, November 4: Miss A. De Zavala is to release a statement maintaining that two children escaped the Alamo defeat. History holds that only a woman and her child survived the Alamo battle November 4, 1901, p. -

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor

University of Mary Hardin-Baylor Institutional Fact Book 2008-2009 Fact Book 2008-2009 Published February 2010 Offi ce of Institutional Effectiveness and Research [email protected] (254) 295-5032 (254) 295-5052 (fax) University of Mary Hardin-Baylor iii Fact Book 2008-2009 February 2010 This Fact Book for the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor presents current and historical information about the institution and its students, providing a variety of summary and statistical information relating to the many functions of the university. Many of the reports show longitudinal trends over several years. The data presented are reliable and conform to generally accepted defi nitions. We hope that you will fi nd this Fact Book to be useful, especially in your role as planner, decision-maker, and evaluator. To provide the most accurate and comparable data, it is necessary to utilize infor- mation from the entire year, although in some cases, data are best presented for fall semesters only. As a result, the Fact Book addresses the preceding, rather than the current, year. The format of the data follows the institutional academic year begin- ning with the fall semester unless the title indicates fi scal year, which runs from June 1st through May 31st. In accordance with government regulations, our offi cial count day is the 8th day of classes. For comparative purposes, older data may be obtained from earlier editions of the Fact Book. Copies of those previous editions may be found in Townsend Memorial Library, the UMHB Offi ce of the Provost/Vice President for Academic Affairs, and the UMHB Offi ce of Institutional Effectiveness and Research. -

Texas Public Schools and Charters, Directory, October 2007

Texas Public Schools and Charters, Directory, October 2007 2006-07 Appraised Tax rate Mailing address Cnty.-dist. Sch. County and district enroll- valuation Main- County, district, region, school and phone number number no. superintendents, principals Grades ment (thousands) tenance Bond 001 ANDERSON 001 CAYUGA ISD 07 P O BOX 427 001-902 DR RICK WEBB 570 $298,062 .137 .000 CAYUGA 75832-0427 PHONE - (903) 928-2102 FAX - (903) 928-2646 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL CAYUGA H S (903) 928-2294 001 DANIEL SHEAD 9-12 165 CAYUGA MIDDLE (903) 928-2699 041 SHERRI MCINNIS 6-8 133 CAYUGA EL (903) 928-2295 103 TRACIE CAMPBELL EE-5 272 ELKHART ISD 07 301 E PARKER ST 001-903 DR JOSEPH GLENN HAMBRICK 1321 $162,993 .137 .000 ELKHART 75839-9701 PHONE - (903) 764-2952 FAX - (903) 764-2466 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL ELKHART H S (903) 764-5161 001 TIMOTHY JOHN RATCLIFF 9-12 362 ELKHART MIDDLE (903) 764-2459 041 JAMES RONALD MAYS JR 6-8 287 ELKHART EL (903) 764-2979 101 MIKE MOON EE-5 672 DAEP INSTRUCTIONAL ELKHART DAEP 002 KG-12 0 FRANKSTON ISD 07 P O BOX 428 001-904 AUSTIN THACKER 789 $251,587 .133 .006 FRANKSTON 75763-0428 PHONE - (903) 876-2556 ext:222 FAX - (903) 876-4558 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL FRANKSTON H S (903) 876-3219 001 NICCI COOK 9-12 248 FRANKSTON MIDDLE (903) 876-2215 041 CHRIS WHITE 6-8 188 FRANKSTON EL (903) 876-2214 102 MARY PHILLIPS PK-5 353 NECHES ISD 07 P O BOX 310 001-906 RANDY L SNIDER 353 $72,781 .137 .000 NECHES 75779-0310 PHONE - (903) 584-3311 FAX - (903) 584-3686 REGULAR INSTRUCTIONAL NECHES H S (903) 584-3443 002 JOE ELLIS 7-12 138 NECHES EL -

Smith Alumnae Quarterly

ALUMNAEALUMNAE Special Issueue QUARTERLYQUARTERLY TriumphantTrT iumphah ntn WomenWomen for the World campaigncac mppaiigngn fortififorortifi eses Smith’sSSmmitith’h s mimmission:sssion: too educateeducac te wwomenommene whowhwho wiwillll cchangehahanngge theththe worldworlrld This issue celebrates a stronstrongerger Smith, where ambitious women like Aubrey MMenarndtenarndt ’’0808 find their pathpathss Primed for Leadership SPRING 2017 VOLUME 103 NUMBER 3 c1_Smith_SP17_r1.indd c1 2/28/17 1:23 PM Women for the WoA New Generationrld of Leaders c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd c2 2/24/17 1:08 PM “WOMEN, WHEN THEY WORK TOGETHER, have incredible power.” Journalist Trudy Rubin ’65 made that statement at the 2012 launch of Smith’s Women for the World campaign. Her words were prophecy. From 2009 through 2016, thousands of Smith women joined hands to raise a stunning $486 million. This issue celebrates their work. Thanks to them, promising women from around the globe will continue to come to Smith to fi nd their voices and their opportunities. They will carry their education out into a world that needs their leadership. SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY Special Issue / Spring 2017 Amber Scott ’07 NICK BURCHELL c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd 1 2/24/17 1:08 PM In This Issue • WOMEN HELPING WOMEN • A STRONGER CAMPUS 4 20 We Set Records, Thanks to You ‘Whole New Areas of Strength’ In President’s Perspective, Smith College President The Museum of Art boasts a new gallery, two new Kathleen McCartney writes that the Women for the curatorships and some transformational acquisitions. World campaign has strengthened Smith’s bottom line: empowering exceptional women. 26 8 Diving Into the Issues How We Did It Smith’s four leadership centers promote student engagement in real-world challenges. -

IDIOMS-MODISMOS Proverbs-Refranes "Modismo" En Ingles Es "Figure of Speech" There Is More Than One Way to Skin a Cat- Cada Quien Tiene Su Manera De Matar Pulgas

IDIOMS-MODISMOS Proverbs-Refranes "modismo" en ingles es "figure of speech" There is more than one way to skin a cat- Cada quien tiene su manera de matar pulgas. This is a work in progress. I made an earnest effort to achieve accuracy, but I do not guarantee it to be error free. If you have any suggested changes, please forward them to me. [email protected] A-Game…… lo mejor de ti, mostrar nada menos que tu mejor disposición/actitud Absence makes the heart grow fonder La ausencia alimenta al corazón To have an act for it (a gift,ability, a way) to have game Tener un don La ausencia es al amor lo que al fuego el aire: que apaga el pequeño y aviva el grande. Actions speak louder than words. Los hechos valen más que las palabras. All talk and no action Las palabras se las lleva el viento. All mouth and no trousers Mucho ruido y pocas nueces. Actions speak louder than words. El movimiento se demuestra andando. Act out. Mal comporatamiento. Impulsividad Act up.. (máquina) no anda bien/ funcionar mal Its acting up.. Ya vuelve a las andadas (persona) portarse mal, dar lata/guerra Adding my two cents in. Agregar mi propia cosecha. All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. All thumbs. Torpe, patoso Hay que divertirse y dejar de lado el trabajo por un rato A fool and his money is soon parted - El vivo vive del tonto y el tonto de su trabajo. All good things must come to an end - Lo bueno dura poco. -

Felix Tijerina

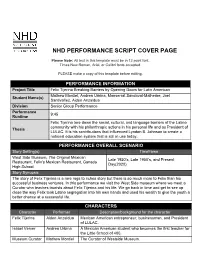

NHD PERFORMANCE SCRIPT COVER PAGE Please Note: All text in this template must be in 12 point font. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri fonts accepted. PLEASE make a copy of this template before editing. PERFORMANCE INFORMATION Project Title Felix Tijerina Breaking Barriers by Opening Doors for Latin American Mathew Montiel, Andrea Urbina, Monserrat Sandoval-Malherbe, Joel Student Name(s) Santivañez, Aiden Anzaldua Division Senior Group Performance Performance 9:45 Runtime Felix Tijerina tore down the social, cultural, and language barriers of the Latino community with his philanthropic actions in his personal life and as President of Thesis LULAC. It is his contributions that influenced Lyndon B. Johnson to create a national education system that is still in use today. PERFORMANCE OVERALL SCENARIO Story Setting(s) Timeframe West Side Museum, The Original Mexican Late 1920’s, Late 1950’s, and Present Restaurant, Felix’s Mexican Restaurant, Ganado Day(2020) High School Story Synopsis The story of Felix Tijerina is a rare rags to riches story but there is so much more to Felix than his successful business ventures. In this performance we visit the West Side museum where we meet a Curator who teaches tourists about Felix Tijerina and his life. We go back in time and get to see up close the way Felix took Latino segregation into his own hands and used his wealth to give the youth a better chance at a successful life. CHARACTERS Character Performer Description/background for the character Felix Tijerina Aiden Anzaldua Mexican American entrepreneur, businessman, and President of LULAC. Isabel Verver Andrea Urbina A Mexican American student who becomes the first teacher for the Little School of 400.