Hein Donner the Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lembit Olli 55. Sünniaastapäeva

LEMBIT OLLI 55. SÜNNIAASTAPÄEVA MÄLESTUSTURNIIR KIIRMALES J u h e n d 1. VÕISTLUSTE KORRALDAJA. Võistluse korraldab Tallinna Maleklubi ning võistlust toetavad Tallinna Kultuuri- ja Spordiamet, Kristiine Linnaosa Valitsus ja Eesti Kultuurkapital. 2. AEG JA KOHT. Lembit Olli 55. sünniaastapäeva mälestusturniir toimub 13. juunil 2021. aastal algusega kell 11.00 Tallinnas Tallinna Puuetega Inimeste Koja saalis (Endla 59, Tallinn). Nimeline registreerimine ja osavõtumaksu tasumine 13. juunil kuni 10.30. 3. KORRALDAMINE. Võistlus viiakse läbi individuaalturniirina. Mängitakse šveitsi süsteemis 7 vooru. Mõtlemisaeg on 15 minutit mõlemale vastasele partii lõpuni + iga käigu sooritamiseks lisandub 3 sekundit. 4. OSAVÕTJAD. Osaleda võivad malehuvilised, kes tasuvad osamaksu (mehed 12€; noored sa. 2003 ja nooremad, naised ning seeniorid sa. 1956 ja vanemad 8€). Alates 12.06.2021. a. on osavõtumaks 15€ ja soodustust omavad maletajad 10€. Osavõtumaksu saab kanda Tallinna Maleklubi kontole EE541010220237168226 SEB Pangas või tasuda võistluspäeval sularahas. Eelregistreerimine võistlusele toimub veebipõhises kalenderplaanis kuni 11. juuni 2021 kell 23:59 http://www.maleliit.ee/kalender/ 11. juuniks registreerunud suurmeistrid on osavõtumaksust vabastatud. 5. PAREMUSJÄRJESTUSE SELGITAMINE. Võrdse arvu punktide korral kahel või enamal maletajal selgitatakse paremusjärjestus alljärgnevalt: 1) Buchholtz ühe nõrgema tulemuseta; 2) Buchholtz kahe nõrgema tulemuseta; 3) omavaheline kohtumine. 6. AUTASUSTAMINE. Võistluste kolme paremat ja eriauhindade parimaid -

An Arbiter's Notebook

An Arbiter's Notebook Does Canada Exist? In 1971 Hans Ree and Boris Spassky shared first place at the Canadian Open Championship in Vancouver. Jan Hein Donner wrote an article, wondering how it was possible that Hans Ree made such a good result in Canada, titled Does Canada Exist? in Schaakbulletin 46 (the predecessor to New In Chess). I broach this subject because Canada is not well known as a chess country, but all of the sudden I have received many comments about an incident there. To be honest, it is very sad, especially since the aggrieved party was a young boy. I received letters from Luc Fortin, (Canada); Mike Burr, (USA); Dan Dornian, (Canada); and Larry Luiting, (Canada) regarding my answer in a An Arbiter's previous column. Notebook I have also received some additional information in regards to the incident in the game Sam Lipnowski (2127) vs. Dane Mattson (1730), Round 10, 2004 Geurt Gijssen Canadian Open (Kapuskasing, Ontario). After Black’s 59th move the position was as follows. It appears that Ra8 mate is unstoppable, but Black played 60…Rxg6+ and White answered with 61 fxg6 – Black is suddenly winning because there is no mate after 61…h1=Q. Black then went to the arbiter to obtain new scoresheets with the position as follows (see next diagram): file:///C|/cafe/geurt/geurt.htm (1 of 8) [9/14/2004 11:19:59 AM] An Arbiter's Notebook When he returned to the board, he probably expected White to resign. Instead, Black resigned because he faced mate in the following position (see next diagram): Of course, White cheated by moving the rook from a3 to b3. -

White Knight Review September-October- 2010

Chess Magazine Online E-Magazine Volume 1 • Issue 1 September October 2010 Nobel Prize winners and Chess The Fischer King: The illusive life of Bobby Fischer Pt. 1 Sight Unseen-The Art of Blindfold Chess CHESS- theres an app for that! TAKING IT TO THE STREETS Street Players and Hustlers White Knight Review September-October- 2010 White My Move [email protected] Knight editorial elcome to our inaugural Review WIssue of White Knight Review. This chess magazine Chess E-Magazine was the natural outcome of the vision of 3 brothers. The unique corroboration and the divers talent of the “Wall boys” set in motion the idea of putting together this White Knight Table of Contents contents online publication. The oldest of the three is my brother Bill. He Review EDITORIAL-”My Move” 3 is by far the Chess expert of the group being the Chess E-Magazine author of over 30 chess books, several websites on the internet and a highly respected player in FEATURE-Taking it to the Streets 4 the chess world. His books and articles have spanned the globe and have become a wellspring of knowledge for both beginners and Executive Editor/Writer BOOK REVIEW-Diary of a Chess Queen 7 masters alike. Bill Wall Our younger brother is the entrepreneur [email protected] who’s initial idea of a marketable website and HISTORY-The History of Blindfold Chess 8 promoting resource material for chess players became the beginning focus on this endeavor. His sales and promotion experience is an FEATURE-Chessman- Picking up the pieces 10 integral part to the project. -

New Zealand Chess

NEW ZEALAND CHESS SUPPLIES P.O.Box 42{90 Wainuiomata Phone (04)564-8578 Fax (04)564-8578 New Zealand Email : [email protected] Mall order and wholesale stocklets ol the wideet selection ol modern chess literature ln Austsalasla. Chess sets, boards, clocks, statlonery and al! playlng equlpment. Chess Dlstrlbutors ol all leadlng brands of chess computers and software. Send S.A.E. lor brochure and catalogue (state your intereet). P LASTIC CH ESSMEN'STAU NTON' STYLE . CLU B/TOU R NAMENT STANDARD Official magazine of the New Zealand Chess Federation (Inc.) gomm King, solid, exka weighted, wide felt base (ivory & black matt finish)$28.00 95mm King solid, weighted, felt base (black & white semi-gloss finish) $17.50 Vol 24 Number I February 1998 $3.50 (incl. GSQ Plastic container with clip tight lid for above sets $8.00 FOLDI NG CH ESSBOARDS - CLU B/TO U RNAMENT STAN DARD 480 x 48omm thick cardboard (green and lemon) $6.00 45o x 45o mm thick vinyl (dark brown and off white) $14.50 VINYL CHESSBOARDS - CLUB/TOURNAMENT STANDARD 45o x 47o mm roll-up mat type, algebraic symbols at borders to assist move recognition (green and white) $8.0o 440 x 44omm semi-flex and non{olding, algebraic symbols as above (dark brown and off-white) $9.00 cHESS MOVE TTMERS (CLOCKS) Turnier German-made popular wind-up club clock, brown plastic $69.00 Standard German-made as above, in imitation wood case $79.00 DGT official FIDE digital chess timer ,. $169.00 SAITEK digital game timer $129.00 CLUB AND TOURNAMENT STATIONERY Bundle of 2oo loose score sheets, 80 -

Timman's Triumphs

Jan Timman Timman’s Triumphs My 100 Best Games New In Chess 2020 Contents Explanation of symbols..............................................6 Introduction .......................................................7 Chapter 1 The road to the top (1967-1977) .........................13 Chapter 2 The blockade (1978-1980) . .67 Chapter 3 Best of the West (1981-1985)...........................113 Chapter 4 The battle for the world title (1986-1993) . .175 Chapter 5 The world title starts getting out of reach (1994-2000) ...237 Chapter 6 In the new millennium (2001-2019)....................291 Index of players ..................................................345 Index of openings ................................................349 5 Introduction In August 2018, I started making a selection of 100 of my best games for this book. As I had expected, it was a difficult task. When you’ve had a long career in chess, and played many thousands of games, there will be hundreds among them on which you can look back with satisfaction. Siegbert Tarrasch published his book Dreihundert Schachpartien in 1895, when he was 33 years old. In such a case, with so many games, the selection process is much ‘looser’. In 1998, Anatoly Karpov also published a selection of 300 games from a period of three decades. Thus, he, too, had more freedom to show all his special victories to the public. I myself published Timman’s Selected Games with Cadogan in 1995, which was brought out by New In Chess under the title Chess the Adventurous Way. It features 80 games from the period 1983-1994. Curiously, I have only included 10 games from that selection in this book. This illustrates the difficulties I experienced with my new selection. -

Eesti Naiste Maleliikumine Ärkas Hilja Nagu Eelmises Malenurgas Lubatud Sai, Siis Teeme Seekord Juttu Eesti Naiste Malemeistriv

Eesti naiste maleliikumine ärkas hilja Nagu eelmises malenurgas lubatud sai, siis teeme seekord juttu Eesti naiste malemeistrivõistluste ajaloost. Kui esimesed Eesti meeste meistrivõistlused leidsid aset juba aastavahetusel 1922/1923, siis naiste seas selgitati esmakordselt parim alles pärast II maailmasõda, 1945. aasta sügisel. Eesti naiste maleliikumise kohta enne II maailmasõda leiame andmeid üsna napilt. Heino Hindre koostatud raamatust “Male Eestis” (1965) saame lugeda: “1925. a on tähiseks meie naiste maleliikumise ajaloos. Esmakordselt toimus Tartus maleturniir tütarlastele, millest võttis osa seitse mängijat. Turniiri võitis Hint (5 p). Esimese võistluse naismaletajaile korraldas Eesti Koolinoorsoo Keskliidu Tartu osakonna malesektsioon. Turniiri võitja nimetati Tartu keskkoolide naismeistriks. Kuid möödus veel 11 aastat, enne kui jõuti esimeste Eesti esivõistluste korraldamiseni naismaletajatele.” 1926. aastal tütarlaste malevõistluste korraldamine Tartus jätkus, turniiri võitis Alma Palm 7 punktiga 8st, järgnesid Endla Tamm (6 p) ja Nadežda Peterson (5 p). Uusi teateid Eesti naiste maleliikumise kohta leiame eelpool nimetatud teosest “Male Eestis” (1965) seoses järgmiste ridadega: “Oli möödunud 11 aastat, kui jälle korraldati turniir naismaletajatele. See toimus 1936. a oktoobris. Korraldajaks oli TEMS (Tallinna Eesti Maleselts). Turniiri võitis Maria Orav, kes oli kaua Eesti “Vera Menchikuks”...” Siinkohal olgu lisatud, et Vera Menchik (1906-1944) oli esimene naiste maailmameister aastail 1927-1944, kes oma tollastest rivaalidest -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 2 • Issue 5 September/October 2011 Albert Einstein Arrested Chess Players and Chess Prison The Geography of Chess and HOW CHESS SPREAD ACROSS THE NATIONS Chess Chess Tournaments Isaac Asimov and Chess White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine Table of Contents contents EDITORIAL- “My Move” 3 4 ARTICLE- Albert Einstein and Chess INTERACTIVE CONTENT FEATURE- Chess in Prison 8 ARTICLE- Arrested Chess Players 11 ________________ • Click on title in Table of Contents HUMOR- How to Annoy Your Opponent 16 to move directly to page. NEWS - Chess News around the World 17 • Click on “White Knight Review” on the top of each HISTORY- Chess Tournaments 18 page to return to Table of Contents. ARTICLE- Isaac Isimov and Chess 23 • Click on red type to continue to next page FEATURE- The Geography of Chess 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW-“Beyond Deep Blue: 28 • Click on email to Chess in the Stratosphere” open by Monty Newborn up email program • Click up URLs to ANNOTATED GAME -Robert McGuire – 29 go to Tibor Weinberger websites. COMMENTARY- “Ask Bill” 31 September-October 2011 White Knight Review September/October 2011 My Move [email protected] editorial -Jerry Wall The great thing about chess is that anybody can play it. From the very young to the elderly, from the very poor to the affluent. It crosses race barriers, economical status, and even intellectual acuity. It can be White Knight enjoyed at any level and in just about any place you can set up a board. -

Neurology, Psychiatry and the Chess Game: a Narrative Review Neurologia, Psiquiatria E O Jogo De Xadrez: Uma Revisão Narrativa Gustavo Leite FRANKLIN1, Brunna N

https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20190187 VIEW AND REVIEW Neurology, psychiatry and the chess game: a narrative review Neurologia, psiquiatria e o jogo de xadrez: uma revisão narrativa Gustavo Leite FRANKLIN1, Brunna N. G. V. PEREIRA2, Nayra S.C. LIMA3, Francisco Manoel Branco GERMINIANI1, Carlos Henrique Ferreira CAMARGO4, Paulo CARAMELLI5, Hélio Afonso Ghizoni TEIVE1, 4 ABSTRACT The chess game comprises different domains of cognitive function, demands great concentration and attention and is present in many cultures as an instrument of literacy, learning and entertainment. Over the years, many effects of the game on the brain have been studied. Seen that, we reviewed the current literature to analyze the influence of chess on cognitive performance, decision-making process, linking to historical neurological and psychiatric disorders as we describe different diseases related to renowned chess players throughout history, discussing the influences of chess on the brain and behavior. Keywords: cognition; recreational games; neurology; psychiatry; decision making; behavior; history. RESUMO O jogo de xadrez compreende diferentes domínios da função cognitiva, exige grande concentração e atenção e está presente em muitas culturas como instrumento de alfabetização, aprendizado e entretenimento. Ao longo dos anos, muitos efeitos do jogo no cérebro foram estudados. Dessa forma, revisamos a literatura atual para analisar a influência do xadrez no desempenho cognitivo, no processo de tomada de decisão, vinculando-a a distúrbios neurológicos e psiquiátricos históricos ao descrevermos diferentes doenças relacionadas a renomados jogadores de xadrez ao longo da história, discutindo as influências do xadrez no cérebro e no comportamento. Palavras-chave: cognição; jogos recreativos; neurologia; psiquiatria; tomada de decisões; comportamento; história. -

Geschichte Die Jahre 1986-1993

Geschichte Die Jahre 1986‐1993 Biel International Chess Festival Die Jahre 1986‐1993 Seit 1986 nehmen sowjetische Spieler am Grossmeisterturnier teil. Sie spielen eine dominierende Rolle, was sich unter anderem in den Siegen von Lev Polugajevski und Vassily Iwantschuk und natürlich der Überlegenheit von Anatoly Karpov zeigt. Letzterer kann sich insgesamt drei Mal durchsetzen, erstmals 1990. Die Turniere werden immer stärker und die Konkurrenz grösser. Der Sommer 1993 bildet einen weiteren Höhepunkt mit der erneuten Organisation eines Interzonenturniers mit 73 Spielern aus der ganzen Welt. Sieger wird Boris Gelfand. 1986: Eine neue Dimension Die Zuschauer und die Organisatoren sprechen von einem Übergangsjahr zwischen dem Interzonenturnier 1985 und dem Turnier 1987, dem zwanzigjährigen Jubiläum. Aber sie steigern sogar noch das Turnierangebot mit einem Grossmeisterturnier mit der erstmals erreichten Kategorie 12 sowie einem weiteren geschlossenen Turnier und einem Damen Turnier, das die Georgierin Nana Alexandria gewinnt. Nicht zu vergessen sind die weiteren Open, die sich über mehrere Tage oder sogar über die ganze Dauer erstrecken. Das Ganze ist aber nur durch einen Sponsorwechsel möglich, indem die UBS nach 5 Jahren den Platz der Credit Suisse überlässt. Dr. William Wirth, einer der Generaldirektoren der Grossbank mit Hauptsitz in Zürich, engagiert sich stark für die Unterstützung des Schachspiels. So profitieren ebenfalls andere Veranstalter vom Schachengagement der Bank, unter anderem auch der Schweizerische Schachverband. Die Unterstützung wird bis ins Jahr 1997 dauern. Es gibt drei Neuheiten zu erwähnen: Erstens können die Resultate über Videotext eingesehen werden, zweitens nimmt zum ersten Mal überhaupt ein Schachcomputer („Mephisto Amsterdam“) an einem Open teil und drittens wird ein ehemaliger Weltmeisterschaftskandidat, Lev Polugajevski aus der Sowjetunion, ins Grossmeisterturnier eingeladen. -

The Magic Year of 1971

The Magic Year an interesting alternative. representatives (each) from Oregon 14.Rc1 c6 15.Qh5 Qxh5 16.Nxh5 0–0 and Washington and two from British of 1971 17.Bc4 Columbia. Players drew lots to see which opponent they would not face. Bob Zuk By John Donaldson of Surrey, B.C., won, scoring 5-1. Viktors Pupols and future Grandmaster Peter Chess has a long and rich tradition Biyiasas shared second and third a half in the Northwest with many important point back. The remaining scores were: 4. competitions held in the region the George Krauss 3 ½ 5. Mike Franett 3; 6. past century including several U.S. and Mike Morris 1 ½ 7-8. Clark Harmon and Canadian Championships. It’s not easy to Mike Montchalin 1. pick one year as the most memorable, but if forced to choose I would select 1971 The following game forced Biyiasas as both World Champion Boris Spassky to play catch-up from the get-go. and soon-to-be titleholder Bobby Fischer played in Vancouver. Position after 17.Bc4 Mike Franett The first major event to be completed Peter Biyiasas [A42] in 1971 was the Washington State 17...b5? Northwest Invitational Championship in February. The annual 17...g6 18.Ng3 Kg7 with equal chances. Portland, OR (1) invitational event, dating back to the early March 5, 1971 1930s, was won by John Braley with 18.Be2 Nc5 a score of 7-0 with Viktors Pupols two 1.d4 g6 2.c4 Bg7 3.e4 d6 4.Nc3 Nc6 18...Rac8 19.Ng3 and the knight comes to 5.Be3 e5 6.d5 Nce7 7.g4 f5 points behind him. -

TIDSKRIFT Fö FÖR SCHACK

TIDSKRIFT fö FÖR SCHACK / TIDSKRIFT FÖR SCHACK NR 6 GRUNDAD 1895 JULI -- AUGUSTI Tidskrift för Schack är officiellt organ och mediemsblad för Sveriges Schackförbund. Ägare: Sveriges Schackförbund. Kanstliadress: Slottsgatan 155, 602 20 Norrköping, tel O11/10 74 20. Redaktör och ansvarig utgivare: Bo Plato, Gethornskroken 21, 28149 Hässleholm, tel 0451/128 50, telefax 0451/147 90. Prenumerationer och ekonomi: Ingemar Eriksson, Sveriges Schackförbund, Slotts- gatan 155, 602 20 Norrköping, tel 011/10 74 20 (arb), 011/724 67 (bost). SSF:s Publikationskommitté: Stbig Jonasson, Bo Plato, Ingemar Eriksson, Ulrika Swan. Prenumerationer: Samtliga prenumeranter är medlemmar av Tidskrift för Schacks HANINGE 1997 Kamratförbund. Prenumerationsavgiften för 1997 är för medlemmar 1 Sveriges Schackförbund 320:-, för övriga 350:-- Stödprenumeration 425:-. BH I SM-tävlingarna i Torvalla sporthall i Haninge gjordes totalt 759 Annonspriser: Helsida 2000:—, halvsida I 200:-, kvartssida 700:—, sista sidan av om- starter av 651 deltagare. Det är —- med undantag för Haparanda 1994 slaget 3 000:-. —- den lägsta startsiffran på 25 år. För annonsörer som sysslar med schacklig verksamhet utgår 50 96 rabatt. 3 Av tradition står Stockholms Schackförbund för SM vart tionde år, I Eriksdalshallen Postgiro: 6046 34-6. 1987 redovisades 1 017 starter, i Älvsjömässan tio år tidigare 1 126 (alla tiders rekord). Mot den bakgrunden ter sig 1997 års siffra generande tåg. Var hittar man förklaringen? All korrespondens sänds till någon av ovan angivna adresser. 0 Generellt har SM-deltagandet under innevarande decennium varit lägre än under re- Tryck: Norra Skåne Offset, Hässleholm kordåren på 1970-talet. På senare tid kan det säkert delvis förklaras av de dåliga tiderna — många har helt enkelt ont om pengar, och det är numera rätt kostsamt att vara med i SM. -

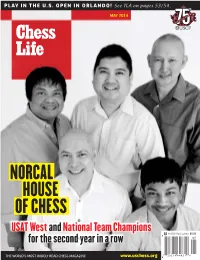

PLAY in the U.S. OPEN in ORLANDO! See TLA on Pages 53/54

PLAY IN THE U.S. OPEN IN ORLANDO! See TLA on pages 53/54. MAY 2014 FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU A USCF PublicationMAY $5.95 05 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 4/9/2014 8:45 PM Page 1 The Ocial Chess Shop of the U.S. Chess Federation NEW!USCF Sales is now an ocial distributor of Sahovski EvgenyInformant Sveshnikov Chess256 pages - $29.95 titles! developments and presents a number of cunning new ideas, many of which come from his Winning with the Najdorf Sicilian NEW! An Uncompromising Repertoire for Black Zaven Andriasyan 240 pages - $29.95 Armenian grandmaster and former World Junior Champion Zaven Andriasyan has found repertoire. New In Chess 2013/3 NEW! The Worlds Premier Chess Magazine 106 pages - $12.99 Garry Kasparov on Magnus Carlsen / Nigel Short: Terror Tourism or my wife in a hijab / Pavel Eljanov: why I played a three-move draw at the Reykjavik Open / How 5 Ukrainian girls broke the Chinese hegemony / Willy Hendriks, author of Move First Think Later Luke McShane / Jan Timman dissects Svidlers opening repertoire / beauty prizes in B0119INFMonaco / and much more- $39.95 ... Chess Informant 119 - Viking Edition The Periodical the Pros Use and Create Millionaire_Layout 1 4/9/2014 8:53 PM Page 1 02-2014_membership_ad 3/12/2014 3:23 PM Page 1 2014 Membership Options Choose Between Premium and Regular USCF Memberships Join now at uschess.org/join or call 1-800-903-8723, ext. 4 PREMIUM USCF MEMBERSHIP RATES PREMIUM MEMBERSHIP CATEGORY 1 YEAR 2 YEAR 3 YEAR PRINTED COPY of Chess Life (monthly) ADULT $ $ $ or Chess Life for Kids (bimonthly) plus 46 84 122 SCHOLASTIC (1) (6 ISSUES CL4K) $ $ $ all other benefits of regular membership.