Brief for Respondents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

65 Tax L. Rev. 241 2011-2012

DATE DOWNLOADED: Sun Sep 26 04:12:46 2021 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: 65 Tax L. Rev. 241 2011-2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://hn3.giga-lib.com/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your license, please use: Copyright Information The Case for a "Super-Matching" Rule YARON Z. REICH* I. Introduction ............................................ 242 II. Overview of Matching and Mismatches ................. 245 III. The Matching Concept and Mismatches in Various A reas ................................................... 248 A. Character: Capital vs. Ordinary .................... 248 B . T im ing .............................................. 251 C. Hedging, Straddles, and Other Approaches to Matching Character and Timing .................... 254 1. Hedging Transactions ........................... 254 2. Section 475 ..................................... 260 3. Straddles ........................................ 263 4. Foreign Currency Hedging Transactions ........ 265 D. International Tax Provisions ........................ 268 1. Source .......................................... 269 a. In G eneral .................................. 269 b. Interest Expense ............................ 270 c. Interest Equivalents ........................ 274 d. Foreign Currency Sourcing Rules ........... 274 e. Personal -

Reemployment of Retired Members: Federal Tax Issues

MARYLAND STATE RETIREMENT AND PENSION SYSTEM REEMPLOYMENT OF RETIRED MEMBERS - FEDERAL TAX ISSUES There are two key tax issues related to the reemployment of individuals by the State or participating governmental units who are retirees of the Maryland State Retirement and Pension System: (1) the tax qualification of the plans under the Maryland State Retirement and Pension System; and (2) the possibility of the imposition of the 10% early distribution tax on benefits received by retirees. The following information is provided in order that State and participating employers may better understand the rules. 1. PLAN QUALIFICATION – A defined benefit retirement plan, such as the plans under the Maryland State Retirement and Pension Plan, must meet many requirements under the Internal Revenue Code in order to be a “qualified plan” under the Code and receive certain important tax advantages. One of those requirements provides that, in general, a member may not withdraw contributions made by the employer, or earnings on such contributions, before normal retirement, termination of employment, or termination of the plan. Rev. Rul. 74-254, 1974-1 C.B. 94. “Normal retirement age cannot be earlier than the earliest age that is reasonably representative of a typical retirement age for the covered workforce.” Prop. Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.401(a) – 1(b)(1)(i). A retirement age that is lower than 65 is permissible for a governmental plan if it reflects when employees typically retire and is not a subterfuge for permitting in-service distributions. PLR 200420030. Therefore, as a matter of plan qualification, retirement benefits may be paid to an employee who reaches “normal retirement age” once the employee retires and separates from service, and the reemployment of such a retiree by the same employer should not raise concerns regarding plan qualification. -

Going from the Frying Pan Into the Fire? a Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations Joseph Tobin

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Business Law Review 10-1-2008 Going from the Frying Pan into the Fire? A Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations Joseph Tobin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr Part of the Taxation-Federal Commons Recommended Citation Joseph Tobin, Going from the Frying Pan into the Fire? A Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations, 17 U. Miami Bus. L. Rev. 211 (2008) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Business Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING FROM THE FRYING PAN INTO THE FIRE? A CRITIQUE OF THE U.S. TREASURY'S NEWLY PROPOSED SECTION 987 CURRENCY REGULATIONS JOSEPH TOBIN* INTRODUCTION .............................. 213 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF U.S. TAXATION OF CURRENCY GAINS AND LOSSES ............................ 217 A. Chaos in the Courts: The Early Case Law on Taxation of Currency Gains and Losses .................. 217 1. Bowers v. Kerbaugh-Empire Co .......... 217 2. B.F. Goodrich Co. v. Commissioner ..... 218 3. KVP Sutherland Paper Co. v. United States 219 4. International Flavors & Fragrances v. Commissioner ....................... 220 B. The IRS's Administrative Response: Revenue Ruling 75-106 and Revenue Ruling 75-107 ....... 222 1. Revenue Ruling 75-106 and the "Net Worth M ethod". -

Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies

Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law Volume 13 Issue 1 Journal of Natural Resources & Article 2 Environmental Law, Volume 13, Issue 1 January 1997 Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies Martin Van Brauman United States Internal Revenue Service Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/jnrel Part of the Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons, Taxation-Transnational Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Van Brauman, Martin (1997) "Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies," Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/jnrel/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAx PLANNING FOR FOREIGN EXPANSION BY U.S. PETROLEUM COMPANIES MARTIN VAN BRAUMAN* I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to provide a basic overview of the tax planning considerations for expansion in foreign petroleum exploration and production operations by U.S. oil companies, with two typical examples of reorganizing foreign branches of U.S. corporations into foreign corporations. U.S. companies have many options in deciding how to begin and expand foreign operations--from the debt capitalization and financing of a foreign entity to the contribution of property to a foreign entity. -

The Fairtax Treatment of Housing

A FairTaxsm White Paper The FairTax treatment of housing Advocates of tax reform share a common motivation: To iron out the mangled economic incentives resulting from statutory inequities and misguided social engineering that perversely cripple the American economy and the American people. Most importantly, ironing out the statutory inequities of the federal tax code need not harm homebuyers and homebuilders. The FairTax does more than do no harm. The FairTax encourages home ownership and homebuilding by placing all Americans and all businesses on equal footing – no loopholes, no exceptions. A specific analysis of the impact of the FairTax on the homebuilding industry/the housing market shows that the new homebuilding market would greatly benefit from enactment of the FairTax. The analysis necessarily centers upon two issues: (1) Whether the FairTax’s elimination of the home mortgage interest deduction (MID) adversely impacts the housing market (new and existing) in general, and home ownership and the homebuilding industry specifically; and (2) Whether the FairTax’s superficially disparate treatment of new vs. existing housing has an adverse impact on the market for new homes and homebuilding. The response to both of the above questions is no. Visceral opposition to the repeal of a “good loophole” such as the MID is understandable, absent a more thorough and empirical analysis of the impact of the FairTax vs. the MID on home ownership and the homebuilding industry. Such an analysis demonstrates that preserving the MID is the classic instance of a situation where the business community confuses support for particular businesses with support for enterprise in general. -

Income-Tax Purposes and Not for Transfer-Tax Purposes, and Vice Versa • There Is No “Perfect” Holding Structure for U.S

Texas Tax Lawyer A Tax Journal Winter 2016 • Vol. 43 • No. 2 www.texastaxsection.org TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM OUR LEADER: Click on title to jump to article • The Chair's Message Alyson Outenreath, Texas Tech University, School of Law UPCOMING CLE EVENTS: • Annual Property Tax Seminar April 25, 2016 – Austin, Texas • Tax Section Annual Meeting CLE June 17, 2016 – Fort Worth, Texas SPECIAL ATTENTION: • Submit a Nomination – Outstanding Texas Tax Lawyer Award Nomination Form • Apply Today – Law Student Scholarship Application SPECIAL RECOGNITIONS: • Congratulations to the 2016 Texas Tax Legend Stanley Blend, San Antonio • Hats Off to the 2016-2017 Leadership Academy Class ARTICLES: • New Partnership Tax Audit Rules Michael J. Donahue, Gardere • S Corporation Opportunities and Pitfalls Christina A. Mondrik, Mondrik & Associates 1 • Where is my Secret Decoder Ring? Decoding and Applying Local Tax Rates Christina A. Mondrik, Mondrik & Associates • Who Can Sign Tax Returns and Make Tax Elections: A review of who has signature authority to file tax returns and make tax elections Kenneth S. Freed, Crady, Jewett & McCulley, LLP • New Allocation Regulations Provide Flexibility for Issuers of Tax Exempt Bonds Peter D. Smith, Norton Rose Fulbright • Resurgence of EOR Credits: Oil Tax Planning Opportunity Drew Willey, Drew Willey Law • EEOC’s Attempt to Regulate Employer Instituted Wellness Plan Struck Down Alexia Noble, Polsinelli, PC Henry Talavera, Polsinelli, PC • Addressing the Corporate Inversion Loophole: A Proposal to Redefine Domestic Corporation Status Sara Anne Giddings, Smith Rose Finley, P.C. PRACTITIONER’S CORNER: • Materials from the 18th Annual International Tax Symposium o U.S. International Tax Developments James P. -

Traditional Individual Retirement Arrangements (Iras)

(6-2010) TRADITIONAL INDIVIDUAL RETIREMENT ARRANGEMENTS (Traditional IRAs) List of Required Modifications and Information Package (LRMs) (For use with prototype traditional IRAs intending to satisfy the requirements of Code § 408(a) or (b).) Material added since the 3-2002 LRMs is underlined. This information package contains samples of provisions that have been found to satisfy certain specific requirements of the Internal Revenue Code as amended through the Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008 (“WRERA”), Pub. L. 110-458. Such language may or may not be acceptable in specific IRAs, depending on the context. We have prepared this package to assist sponsors who are drafting IRAs. To expedite the review process, sponsors are encouraged to use the language contained in this package. Part A, provisions 1-12, applies to individual retirement accounts under Code § 408(a). Part B, provisions 13-22, applies to individual retirement annuities under § 408(b). ________________________________________________________________ PART A: ACCOUNTS - Trust or custodial accounts under Code § 408(a). (1) Statement of Requirement: The IRA is organized and operated for the exclusive benefit of the individual, Code § 408(a). Sample Language: The account is established for the exclusive benefit of the individual or his or her beneficiaries. If this is an inherited IRA within the meaning of Code § 408(d)(3)(C) maintained for the benefit of a designated beneficiary of a deceased individual, references in this document to the “individual” are to the deceased individual. (2) Statement of Requirement: Maximum permissible annual contribution and restrictions on kinds of contributions, Code §§ 72(t)(2)(G), 219(b), 408(a)(1), 408(d)(3)(C), 408(d)(3)(G), 1 408(p)(1)(B) and 408(p)(2)(A)(iv). -

Section 501 on the Ground That All of Its Profits Are Payable to One Or More Organizations Exempt from Taxation Under Section 501

F. IRC 502 - FEEDER ORGANIZATIONS 1. Introduction An organization described in IRC 502 does not qualify for exemption under any paragraph of IRC 501(c). The purpose of this article is to discuss some of the basic issues presented by IRC 502, to explain how it should be interpreted and applied, and to consider the amount of unrelated business activity that an exempt charitable organization may engage in. IRC 502 provides that an organization operated for the primary purpose of carrying on a trade or business for profit shall not be exempt under IRC 501 on the ground that all of its profits are payable to one or more organizations exempt under IRC 501. 2. Purpose of Feeder Provisions A brief consideration of the reasons for the enactment of IRC 502 provides some insight as to how it should be interpreted. There was growing concern, particularly after World War II, about the increasing amount of business activities carried on by exempt organizations, particularly, charitable organizations. In a series of cases involving taxable years prior to 1951, certain organizations popularly called "feeder organizations" were held exempt from federal income tax under the predecessor to IRC 501(c)(3), even though their sole activity was engaging in commercial business, and the only basis for exemption was the fact their profits were payable to specified exempt organizations. See Roche's Beach, Inc. v. Commissioner, 96 F. 2d 776 (1938); C. F. Mueller Company v. Commissioner, 190 F. 2d 120 (1951). The courts held that the exclusive purpose required by the statute was met when the only object of the organization was religious, scientific, charitable, or educational, without regard to the method of obtaining funds necessary to effectuate the objective. -

Home Workers and the Debate Over "Who's a Statutory Employee" Under the Internal Revenue Code

HOME WORKERS AND THE DEBATE OVER "WHO'S A STATUTORY EMPLOYEE" UNDER THE INTERNAL REVENUE CODE ROBERT \V VVOOD ANI) CIlIUSTOPIiER A. KARACIIALE ifferent governmental agencies use different tests for determining who is <1n D employee and who is not. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) typically uses one test,' the Department of Labor and many employment statutes use another,2 and most state unemployment insurance authorities use another stil\.3 This creates ROBERT W. WOOD CHRISTOPHER A. /?OIlERT W WOOD I'UACT/CI,S KARACHALE a great deal of confusion about what should be a relatively simple question-is a LAW WITH WOOD & POUTEU CIIIUSTOPIIEU KAUACHALE IN SAN FUANCISCO (WWW. /S ,IN ASSOCIATE AT Woov & worker an employee or an independent contractor' WOO DPOUTFU.COM) ANI) IS POUTFU IN SAN FUANCISCO. THE AUTllOU OF TAXATION HI-"Af)VISES INDIVI DUALS AND The test for employee status generally used by the IRS looks to the employer's OF DAMAGE AWAIU)S ANI) IJUSINI;'SS ENTI'I'IESONAHROAD behavioral and financial controls over the worker, as well as the relationship between SETTLEMENT PAYMENTS (4T/-1 IIANGE OF TAX PUNNING AND ED. TAX INSTITUTE, 2009) TAX CONTROVEUSY MATTERS, the parties. This "twenty-factor test" is an uncodified,amorphous, facts and circum AND QUAIIFIFD SETTLEMENT INCI UDING TI-"'" TAXATION FUNDS AND SECTION 468/l OF I),IMAGE AI,VAIIVS AND stances test that, like many of the other tests, tends to provide uneven results. Never (TAX INSTI TUTE, 2009), DEFEUllliD COMPENS ATION, HOTH AVA/tABLE AT WWW. INIJHPFNVJ:NT C:ONTR ACTOU theless, for more than 50 years, the Internal Revenue Code has contained a narrowly TAX1NS TITUTE.COM. -

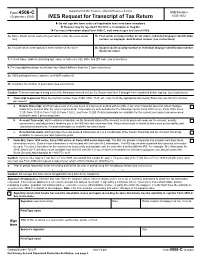

Form 4506-C, IVES Request for Transcript of Tax Return

Department of the Treasury - Internal Revenue Service Form 4506-C OMB Number (September 2020) IVES Request for Transcript of Tax Return 1545-1872 ▶ Do not sign this form unless all applicable lines have been completed. ▶ Request may be rejected if the form is incomplete or illegible. ▶ For more information about Form 4506-C, visit www.irs.gov and search IVES. 1a. Name shown on tax return (if a joint return, enter the name shown 1b. First social security number on tax return, individual taxpayer identification first) number, or employer identification number (see instructions) 2a. If a joint return, enter spouse’s name shown on tax return 2b. Second social security number or individual taxpayer identification number if joint tax return 3. Current name, address (including apt., room, or suite no.), city, state, and ZIP code (see instructions) 4. Previous address shown on the last return filed if different from line 3 (see instructions) 5a. IVES participant name, address, and SOR mailbox ID 5b. Customer file number (if applicable) (see instructions) Caution: This tax transcript is being sent to the third party entered on Line 5a. Ensure that lines 5 through 8 are completed before signing. (see instructions) 6. Transcript requested. Enter the tax form number here (1040, 1065, 1120, etc.) and check the appropriate box below. Enter only one tax form number per request a. Return Transcript, which includes most of the line items of a tax return as filed with the IRS. A tax return transcript does not reflect changes made to the account after the return is processed. -

Additional First-Year Depreciation Allowance. 40.60(1) Assets Acquired After September 10, 2001, but Before May 6, 2003

IAC Ch 40, p.1 701—40.60 (422) Additional first-year depreciation allowance. 40.60(1) Assets acquired after September 10, 2001, but before May 6, 2003. For tax periods ending after September 10, 2001, but beginning before May 6, 2003, the additional first-year depreciation allowance (“bonus depreciation”) of 30 percent authorized in Section 168(k) of the Internal Revenue Code, as enacted by Public Law No. 107-147, Section 101, does not apply for Iowa individual income tax. Taxpayers who claim the bonus depreciation on their federal income tax return must add the total amount of depreciation claimed on assets acquired after September 10, 2001, but before May 6, 2003, and subtract the amount of depreciation taken on such property using the modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) depreciation method applicable under Section 168 of the Internal Revenue Code without regard to Section 168(k). If any such property was sold or disposed of during the tax year, the applicable depreciation catch-up adjustment must be made to adjust the basis of the property for Iowa tax purposes. The gain or loss reported on the sale or disposition of these assets for federal tax purposes must be adjusted for Iowa tax purposes to account for the adjusted basis of assets. The adjustment for both depreciation and the gain or loss on the sale of qualifying assets acquired after September 10, 2001, but before May 6, 2003, can be calculated on Form IA 4562A. See 701—subrule 53.22(1) for examples illustrating how this subrule is applied. -

Page 3158 TITLE 26—INTERNAL REVENUE CODE § 6101

§ 6101 TITLE 26—INTERNAL REVENUE CODE Page 3158 6107. Tax return preparer must furnish copy of re- (Aug. 16, 1954, ch. 736, 68A Stat. 753; Pub. L. turn to taxpayer and must retain a copy or 94–455, title XIX, § 1906(b)(13)(A), Oct. 4, 1976, 90 list. Stat. 1834.) 6108. Publication of statistics of income.2 6109. Identifying numbers. AMENDMENTS 6110. Public inspection of written determinations. 1976—Pub. L. 94–455 struck out ‘‘or his delegate’’ after 6111. Disclosure of reportable transactions. ‘‘Secretary’’. 6112. Material advisors of reportable transactions must keep lists of advisees, etc. § 6102. Computations on returns or other docu- 6113. Disclosure of nondeductibility of contribu- ments tions. 6114. Treaty-based return positions. (a) Amounts shown on internal revenue forms 6115. Disclosure related to quid pro quo contribu- The Secretary is authorized to provide with tions. 6116. Requirement for prisons located in United respect to any amount required to be shown on States to provide information for tax ad- a form prescribed for any internal revenue re- ministration. turn, statement, or other document, that if such 6117. Cross reference. amount of such item is other than a whole-dol- lar amount, either— AMENDMENTS (1) the fractional part of a dollar shall be 2011—Pub. L. 112–41, title V, § 502(b), Oct. 21, 2011, 125 disregarded; or Stat. 460, added items 6116 and 6117 and struck out (2) the fractional part of a dollar shall be former item 6116 ‘‘Cross reference’’. 2007—Pub. L. 110–28, title VIII, § 8246(a)(2)(C)(ii), May disregarded unless it amounts to one-half dol- 25, 2007, 121 Stat.