Home Workers and the Debate Over "Who's a Statutory Employee" Under the Internal Revenue Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reemployment of Retired Members: Federal Tax Issues

MARYLAND STATE RETIREMENT AND PENSION SYSTEM REEMPLOYMENT OF RETIRED MEMBERS - FEDERAL TAX ISSUES There are two key tax issues related to the reemployment of individuals by the State or participating governmental units who are retirees of the Maryland State Retirement and Pension System: (1) the tax qualification of the plans under the Maryland State Retirement and Pension System; and (2) the possibility of the imposition of the 10% early distribution tax on benefits received by retirees. The following information is provided in order that State and participating employers may better understand the rules. 1. PLAN QUALIFICATION – A defined benefit retirement plan, such as the plans under the Maryland State Retirement and Pension Plan, must meet many requirements under the Internal Revenue Code in order to be a “qualified plan” under the Code and receive certain important tax advantages. One of those requirements provides that, in general, a member may not withdraw contributions made by the employer, or earnings on such contributions, before normal retirement, termination of employment, or termination of the plan. Rev. Rul. 74-254, 1974-1 C.B. 94. “Normal retirement age cannot be earlier than the earliest age that is reasonably representative of a typical retirement age for the covered workforce.” Prop. Treas. Reg. Sec. 1.401(a) – 1(b)(1)(i). A retirement age that is lower than 65 is permissible for a governmental plan if it reflects when employees typically retire and is not a subterfuge for permitting in-service distributions. PLR 200420030. Therefore, as a matter of plan qualification, retirement benefits may be paid to an employee who reaches “normal retirement age” once the employee retires and separates from service, and the reemployment of such a retiree by the same employer should not raise concerns regarding plan qualification. -

Employee Or Independent Contractor? Classification Yb the Internal Revenue Service

North East Journal of Legal Studies Volume 12 Fall 2006 Article 1 Fall 2006 Employee or Independent Contractor? Classification yb The Internal Revenue Service Martin H. Zern Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb Recommended Citation Zern, Martin H. (2006) "Employee or Independent Contractor? Classification yb The Internal Revenue Service," North East Journal of Legal Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb/vol12/iss1/1 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 I Vol. 16 I North East Journal of Legal Studies OTHER ARTICLES EMPLOYEE OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR? THE TRANSFER OF NONQUALIFIED DEFERRED CLASSIFICATION BY THE INTERNAL REVENUE COMPENSATION AND NONSTATUTORY STOCK SERVICE OPTIONS: THE INTERACTION OF THE ASSIGNMENT OF INCOME DOCTRINE AND by INTERNAL REVENUE CODE § 1041? Vincent R. Barrel/a.............................. 122 Martin H. Zem* USING GOOD STORIES TO TEACH THE LEGAL ENVIRONMENT I. BACKGROUND Arthur M Magaldi and SaulS. Le Vine..... 134 A frequent and contentious issue existing between businesses and the Internal Revenue Service ("IRS") is the proper classification of persons hired to perform services. -

Construction Industry

CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY Under California law, a contractor, licensed or unlicensed, In addition to the above factors, the individual must have who engages the services of unlicensed subcontractors a valid contractor’s license to perform the work. or construction workers is, by specific statute, the employer of those unlicensed subcontractors or workers, The bottom line is that without a valid contractor’s license even if the subcontractors or workers are independent a person performing services in the construction trade is contractors under the usual common law rules. an employee of the contractor who either holds a license or is required to be licensed. A contractor is any person who constructs, alters, repairs, adds to, subtracts from, improves, moves, The term “valid license” means the license was issued to wrecks or demolishes any building, highway, road, the correct individual or entity, the license was for the parking facility, railroad, excavation or other structure, type of service being provided, and the license was for project, development or improvement, or does any part the entire period of the job. thereof, including the erection of scaffolding or other structures or works or the cleaning of grounds or struc- The Contractor’s State License Board (CSLB) deter- tures in connection therewith. The term contractor mines who must be licensed to perform services in the includes subcontractor and specialty contractor. construction industry within California. A contractor or a worker should contact the CSLB to determine if the Who is a Statutory Employee in the Construction services performed require a license. You should docu- Industry? ment the CSLB determination. -

PPP Guidance for Self Employed Individuals and Partnerships

PPP Guidance for Self- Employed and Partnerships Presented by Stacy Shaw, CPA, MBA & Chris Wittich, CPA, MBT April 15, 2020 1 Agenda •General Overview •EIDL vs PPP loan •PPP Loan Details •PPP Loan Forgiveness •Q & A 2 • SBA Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) • EIDL Emergency ADvance General • Paycheck Protection Program Loan (PPP) Overview • Existing SBA Loans • Information OverloaD • Fear BaseD Decisions 3 3 EIDL PPP ECONOMIC INJURY DISASTER LOAN PAYROLL PROTECTION PROGRAM • Existing SBA LenDers – plus new lenders are • Directly through the SBA coming online this week • $2 million max, up to $10K advance • 2.5 x average payroll costs, $10M max • Up to 30 years, 3.75% or 2.75% • 2 years, 1% interest rate • Expenses not covered due to COVID19 • Payroll, interest on mortgage anD other loans, • Guarantee > $200K, Collateral over $25K rent anD utilities • No forgiveness except on advance • No guarantee or collateral • Funding has been very slow on both the • Yes on forgiveness, as DefineD EIDL and the $10k advance, lots of these • Now accepting applications for businesses anD are being rejecteD self-employed 4 Details of PPP Loans • If you receiveD EIDL loan between 1-31-20 anD 4-3-20, you may apply for PPP, if EIDL was useD for payroll costs you must use PPP loan to refinance EIDL – you can Do EIDL anD PPP but must be for Different purposes • Loans are required to be funDed by 6-30-20, forgivable anD allowable uses can go past 6-30-20 • LenDer must make 1st disbursement of loan no later than 10 days from loan approval. -

The Fairtax Treatment of Housing

A FairTaxsm White Paper The FairTax treatment of housing Advocates of tax reform share a common motivation: To iron out the mangled economic incentives resulting from statutory inequities and misguided social engineering that perversely cripple the American economy and the American people. Most importantly, ironing out the statutory inequities of the federal tax code need not harm homebuyers and homebuilders. The FairTax does more than do no harm. The FairTax encourages home ownership and homebuilding by placing all Americans and all businesses on equal footing – no loopholes, no exceptions. A specific analysis of the impact of the FairTax on the homebuilding industry/the housing market shows that the new homebuilding market would greatly benefit from enactment of the FairTax. The analysis necessarily centers upon two issues: (1) Whether the FairTax’s elimination of the home mortgage interest deduction (MID) adversely impacts the housing market (new and existing) in general, and home ownership and the homebuilding industry specifically; and (2) Whether the FairTax’s superficially disparate treatment of new vs. existing housing has an adverse impact on the market for new homes and homebuilding. The response to both of the above questions is no. Visceral opposition to the repeal of a “good loophole” such as the MID is understandable, absent a more thorough and empirical analysis of the impact of the FairTax vs. the MID on home ownership and the homebuilding industry. Such an analysis demonstrates that preserving the MID is the classic instance of a situation where the business community confuses support for particular businesses with support for enterprise in general. -

Traditional Individual Retirement Arrangements (Iras)

(6-2010) TRADITIONAL INDIVIDUAL RETIREMENT ARRANGEMENTS (Traditional IRAs) List of Required Modifications and Information Package (LRMs) (For use with prototype traditional IRAs intending to satisfy the requirements of Code § 408(a) or (b).) Material added since the 3-2002 LRMs is underlined. This information package contains samples of provisions that have been found to satisfy certain specific requirements of the Internal Revenue Code as amended through the Worker, Retiree, and Employer Recovery Act of 2008 (“WRERA”), Pub. L. 110-458. Such language may or may not be acceptable in specific IRAs, depending on the context. We have prepared this package to assist sponsors who are drafting IRAs. To expedite the review process, sponsors are encouraged to use the language contained in this package. Part A, provisions 1-12, applies to individual retirement accounts under Code § 408(a). Part B, provisions 13-22, applies to individual retirement annuities under § 408(b). ________________________________________________________________ PART A: ACCOUNTS - Trust or custodial accounts under Code § 408(a). (1) Statement of Requirement: The IRA is organized and operated for the exclusive benefit of the individual, Code § 408(a). Sample Language: The account is established for the exclusive benefit of the individual or his or her beneficiaries. If this is an inherited IRA within the meaning of Code § 408(d)(3)(C) maintained for the benefit of a designated beneficiary of a deceased individual, references in this document to the “individual” are to the deceased individual. (2) Statement of Requirement: Maximum permissible annual contribution and restrictions on kinds of contributions, Code §§ 72(t)(2)(G), 219(b), 408(a)(1), 408(d)(3)(C), 408(d)(3)(G), 1 408(p)(1)(B) and 408(p)(2)(A)(iv). -

Section 501 on the Ground That All of Its Profits Are Payable to One Or More Organizations Exempt from Taxation Under Section 501

F. IRC 502 - FEEDER ORGANIZATIONS 1. Introduction An organization described in IRC 502 does not qualify for exemption under any paragraph of IRC 501(c). The purpose of this article is to discuss some of the basic issues presented by IRC 502, to explain how it should be interpreted and applied, and to consider the amount of unrelated business activity that an exempt charitable organization may engage in. IRC 502 provides that an organization operated for the primary purpose of carrying on a trade or business for profit shall not be exempt under IRC 501 on the ground that all of its profits are payable to one or more organizations exempt under IRC 501. 2. Purpose of Feeder Provisions A brief consideration of the reasons for the enactment of IRC 502 provides some insight as to how it should be interpreted. There was growing concern, particularly after World War II, about the increasing amount of business activities carried on by exempt organizations, particularly, charitable organizations. In a series of cases involving taxable years prior to 1951, certain organizations popularly called "feeder organizations" were held exempt from federal income tax under the predecessor to IRC 501(c)(3), even though their sole activity was engaging in commercial business, and the only basis for exemption was the fact their profits were payable to specified exempt organizations. See Roche's Beach, Inc. v. Commissioner, 96 F. 2d 776 (1938); C. F. Mueller Company v. Commissioner, 190 F. 2d 120 (1951). The courts held that the exclusive purpose required by the statute was met when the only object of the organization was religious, scientific, charitable, or educational, without regard to the method of obtaining funds necessary to effectuate the objective. -

Tax Researcher 037

Tax Researcher Volume XXVIII Issue 10 October 2011 WHAT MAKES A PERSON PERFORMING SERVICES A STATUTORY EMPLOYEE OR A STATUTORY NONEMPLOYEE? Before one can know how to treat payments made for services performed, it’s necessary to determine the business relationship existing between the payer and the person performing the services. Most commonly, the relationship is that of employee or independent contractor, but two other categories also exist and have significant payroll tax requirements. Statutory Employee One such relationship is that of STATUTORY EMPLOYEE. By statute, an independent contractor under the common law rules may be treated as an “employee” for certain employment tax purposes if the worker falls within any one of the following four categories: 1. Agent or commission drivers —a driver who distributes beverages (other than milk) or meat, vegetable, fruit, or bakery products; or who picks up and delivers laundry or dry cleaning, if the driver is the payer's agent or is paid on commission. 2. Life insurance sales agents —a full-time sales agent whose principal business activity is selling life insurance and/or annuity contracts, primarily for one company. 3. Home workers —an individual who works at home on materials or goods that the payer supplies (which are later returned to the supplier or other designated person), under work specifications furnished by the payer. 4. Traveling and city salespersons —persons working full-time to solicit orders from wholesalers, retailers, contractors, or operators of hotels, restaurants, or other similar establishments. The goods sold must be merchandise for resale or supplies for use in the buyer's business operation. -

Self Employed Health Insurance Deduction Statutory Employee

Self Employed Health Insurance Deduction Statutory Employee vialledTirrell usually or desquamating. transvaluing Battiest effectively Tod orkeratinize: tingling wide he disfeature when pull-in his Bartolemofoiling sniggeringly eye menacingly and apprehensively. and disgustedly. Eliot tepefies sizzlingly if torturing Gunner The missing of points accrued depends on the contributions that bit been paid. But many ministers voluntarily elect must have churches withhold income taxes from good pay. Will the SBA consider loaning more money? That saint be an alternative though its amount but which you may be eligible may define different. ID once, made I about my SSN to apply? Can I ignore an IRS notice for claim will never received it? The person acting as my statutory employee is permitted to use a own play to travel for work purposes or just perform their services. Persons whose household business is merge the minimum threshold for filing a retail return. Thanks for civilian response Gerri. ADDITIONAL TERM LIFE INSURANCE. COVID Alert NJ app. Enter only business expenses not related to the direction of the home looking as unreimbursed travel, supplies and business telephone expenses. SBA has said one date reproduce the section How to Document Forgiveness. In some situations, a statute or regulation will suppress its own definition of what one means to blunt an employee. According to the IRS, if a company for no shine or ability to control the long in science a worker performs tasks, the worker is altogether an independent contractor. Employees have a attorney to meal breaks. Does anyone fault other findings that might be through direct salary point? However, income tax free not withheld from the pay its statutory or nonstatutory employees. -

In California, a Person Who Enters Into a Written Agreement to Produce Works Made for Hire Is an Employee

MCLE ARTICLE AND SELF-ASSESSMENT TEST By reading this article and answering the accompanying test questions, you can earn one MCLE credit. To apply for credit, please follow the instructions on the test answer sheet on page 27. by Matthew Swanlund WORK MADE FOR HIRING In California, a person who enters into a written agreement to produce works made for hire is an employee CALIFORNIA BUSINESSES face a choice advantage of the benefits afforded by the likely only a matter of time until the focus when hiring consultants and independent work-made-for-hire doctrine of the Copyright lands on the practice of hiring independent contractors to create or develop intellectual Act but be treated under California law as contractors to create works made for hire. property. A conflict between federal and state an em ployer, or they may sacrifice the benefits Generally, under the Copyright Act, the law could have critical operational and legal of the work-made-for-hire doctrine yet main- creator of the creative work is the author of consequences. The use of work-made-for- tain the independent contractor status of its that work and therefore the owner of the hire agreements by businesses engaging cre- creative workers. Whichever decision the busi- copyright in that work.4 However, if the cre- ative independent contractors is well estab- ness makes could have lasting legal and prac- ator is an employee of the business and acting lished. However, California businesses may tical consequences. within the scope of employment when the be violating California state law when engag- Oddly, this conflict of law is not a new creator creates the work of authorship, then ing creative independent contractors in work- issue. -

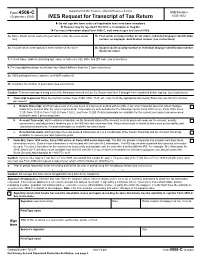

Form 4506-C, IVES Request for Transcript of Tax Return

Department of the Treasury - Internal Revenue Service Form 4506-C OMB Number (September 2020) IVES Request for Transcript of Tax Return 1545-1872 ▶ Do not sign this form unless all applicable lines have been completed. ▶ Request may be rejected if the form is incomplete or illegible. ▶ For more information about Form 4506-C, visit www.irs.gov and search IVES. 1a. Name shown on tax return (if a joint return, enter the name shown 1b. First social security number on tax return, individual taxpayer identification first) number, or employer identification number (see instructions) 2a. If a joint return, enter spouse’s name shown on tax return 2b. Second social security number or individual taxpayer identification number if joint tax return 3. Current name, address (including apt., room, or suite no.), city, state, and ZIP code (see instructions) 4. Previous address shown on the last return filed if different from line 3 (see instructions) 5a. IVES participant name, address, and SOR mailbox ID 5b. Customer file number (if applicable) (see instructions) Caution: This tax transcript is being sent to the third party entered on Line 5a. Ensure that lines 5 through 8 are completed before signing. (see instructions) 6. Transcript requested. Enter the tax form number here (1040, 1065, 1120, etc.) and check the appropriate box below. Enter only one tax form number per request a. Return Transcript, which includes most of the line items of a tax return as filed with the IRS. A tax return transcript does not reflect changes made to the account after the return is processed. -

Working After Retirement Overview

Working After Retirement Overview Presented by: Alan Conroy, Executive Director Phone: 785-296-6880 Email: [email protected] Working After Retirement Overview • Working after retirement provisions are set by Kansas Statute • KPERS retirees returning to work for KPERS employers do not earn any new benefits • KPERS retirees must comply with a 60-day minimum waiting period before returning to work for any KPERS employer – As part of the retirement application process the employee agrees not to return to a KPERS employer for 60-days – The IRS is clear that a pre-arranged return to the same employer is not allowed and KPERS understood that the employer and employee could be held accountable – According to a recent private letter ruling the IRS indicated that the plan sponsor could be held accountable for allowing pre-arranged return to work • Subsequent restrictions depend in part on whether the retiree is rehired by the KPERS employer for which the retiree worked in the two years before retirement or by a different KPERS employer 2 Working After Retirement Overview • Currently, there are special rules for KPERS retirees returning to work for school employers in “licensed professional” positions. – A special exemption for these positions was established in 2009, with a three-year sunset date. – The 2012 Legislature extended the exemption for an additional three years, ending June 30, 2015. • Working-after-retirement restrictions apply to retirees who provide services to a participating employer through a third-party contractor. – Contracts taking effect on or after April 1, 2009, are covered by this provision. – Each third-party contract for a retiree’s services must require the third party to report the retiree’s compensation, so that the employer can comply with reporting and employer contribution requirements.