Eugene Cernan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's First Moon Landing

America’s First Moon Landing (July 21, 1969) Apollo 11, which was launched into his oval mural commemorating America’s Moon landing space from the Kennedy Space Center, embellishes the Brumidi Corridors in the Senate wing of the Florida, began its epic voyage to the Moon on July 16, 1969. On board were Capitol. The mural’s three main elements are: the rocket that Commander Neil A. Armstrong, Lunar propelled the astronauts into orbit; astronauts Neil Armstrong Module Pilot Edwin E. ”Buzz“ Aldrin, Jr., and Buzz Aldrin planting the United States flag on the Moon, and Command Module Pilot Michael with the lunar module Eagle in the background and the space capsule Collins. After 24 hours in lunar orbit, the T command/service module, Columbia, Columbia circling the Moon; and a view of Earth as seen from the Moon. separated from the lunar module, Eagle. Although the Eagle landed on the Moon in the afternoon of July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin began their descent to the lunar surface in the Eagle while Armstrong and Aldrin did not erect the flag until the next morning, which Collins stayed behind to pilot the explains why the scene is dated July 21, 1969. Columbia. The lunar module touched Muralist Allyn Cox painted the work. The son of artists Kenyon down on the Moon at Tranquility Base on July 20, 1969, at 4:17 P.M. EDT.Arm and Louise King Cox, Allyn Cox was born in New York City. He was strong reported, “The Eagle has landed.” educated at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League At 10:56 P.M., Armstrong stepped in New York, and the American Academy in Rome. -

USGS Open-File Report 2005-1190, Table 1

TABLE 1 GEOLOGIC FIELD-TRAINING OF NASA ASTRONAUTS BETWEEN JANUARY 1963 AND NOVEMBER 1972 The following is a year-by-year listing of the astronaut geologic field training trips planned and led by personnel from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Branches of Astrogeology and Surface Planetary Exploration, in collaboration with the Geology Group at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, Texas at the request of NASA between January 1963 and November 1972. Regional geologic experts from the U.S. Geological Survey and other governmental organizations and universities s also played vital roles in these exercises. [The early training (between 1963 and 1967) involved a rather large contingent of astronauts from NASA groups 1, 2, and 3. For another listing of the astronaut geologic training trips and exercises, including all attending and the general purposed of the exercise, the reader is referred to the following website containing a contribution by William Phinney (Phinney, book submitted to NASA/JSC; also http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/alsj/ap-geotrips.pdf).] 1963 16-18 January 1963: Meteor Crater and San Francisco Volcanic Field near Flagstaff, Arizona (9 astronauts). Among the nine astronaut trainees in Flagstaff for that initial astronaut geologic training exercise was Neil Armstrong--who would become the first man to step foot on the Moon during the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969! The other astronauts present included Frank Borman (Apollo 8), Charles "Pete" Conrad (Apollo 12), James Lovell (Apollo 8 and the near-tragic Apollo 13), James McDivitt, Elliot See (killed later in a plane crash), Thomas Stafford (Apollo 10), Edward White (later killed in the tragic Apollo 1 fire at Cape Canaveral), and John Young (Apollo 16). -

In Memory of Astronaut Michael Collins Photo Credit

Gemini & Apollo Astronaut, BGEN, USAF, Ret, Test Pilot, and Author Dies at 90 The Astronaut Scholarship Foundation (ASF) is saddened to report the loss of space man Michael Collins BGEN, USAF, Ret., and NASA astronaut who has passed away on April 28, 2021 at the age of 90; he was predeceased by his wife of 56 years, Pat and his son Michael and is survived by their daughters Kate and Ann and many grandchildren. Collins is best known for being one of the crew of Apollo 11, the first manned mission to land humans on the moon. Michael Collins was born in Rome, Italy on October 31, 1930. In 1952 he graduated from West Point (same class as future fellow astronaut, Ed White) with a Bachelor of Science Degree. He joined the U.S. Air Force and was assigned to the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing at George AFB in California. He subsequently moved to Europe when they relocated to Chaumont-Semoutiers AFB in France. Once during a test flight, he was forced to eject from an F-86 after a fire started behind the cockpit; he was safely rescued and returned to Chaumont. He was accepted into the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. In 1960 he became a member of Class 60C which included future astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Irwin, and Tom Stafford. His inspiration to become an astronaut was the Mercury Atlas 6 flight of John Glenn and with this inspiration, he applied to NASA. In 1963 he was selected in the third group of NASA astronauts. -

President Richard Nixon's Daily Diary, July 16-31, 1969

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest 7/30/1969 A 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest from Don- 7/30/1969 A Maung Airport, Bangkok 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/23/1969 A Appendix “B” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/24/1969 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/26/1969 A Appendix “B” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/27/1969 A Appendix “A” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-3 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 16, 1969 – July 31, 1969 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) rnc.~IIJc.I'" rtIl."I'\ttU 1"'AUI'4'~ UAILJ UIAtU (See Travel Record for Travel Activity) ---- -~-------------------~--------------I PLACi-· DAY BEGA;'{ DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) JULY 16, 1969 TIME DAY THE WHITE HOUSE - Washington, D. -

PEANUTS and SPACE FOUNDATION Apollo and Beyond

Reproducible Master PEANUTS and SPACE FOUNDATION Apollo and Beyond GRADE 4 – 5 OBJECTIVES PAGE 1 Students will: ö Read Snoopy, First Beagle on the Moon! and Shoot for the Moon, Snoopy! ö Learn facts about the Apollo Moon missions. ö Use this information to complete a fill-in-the-blank fact worksheet. ö Create mission objectives for a brand new mission to the moon. SUGGESTED GRADE LEVELS 4 – 5 SUBJECT AREAS Space Science, History TIMELINE 30 – 45 minutes NEXT GENERATION SCIENCE STANDARDS ö 5-ESS1 ESS1.B Earth and the Solar System ö 3-5-ETS1 ETS1.B Developing Possible Solutions 21st CENTURY ESSENTIAL SKILLS Collaboration and Teamwork, Communication, Information Literacy, Flexibility, Leadership, Initiative, Organizing Concepts, Obtaining/Evaluating/Communicating Ideas BACKGROUND ö According to NASA.gov, NASA has proudly shared an association with Charles M. Schulz and his American icon Snoopy since Apollo missions began in the 1960s. Schulz created comic strips depicting Snoopy on the Moon, capturing public excitement about America’s achievements in space. In May 1969, Apollo 10 astronauts traveled to the Moon for a final trial run before the lunar landings took place on later missions. Because that mission required the lunar module to skim within 50,000 feet of the Moon’s surface and “snoop around” to determine the landing site for Apollo 11, the crew named the lunar module Snoopy. The command module was named Charlie Brown, after Snoopy’s loyal owner. These books are a united effort between Peanuts Worldwide, NASA and Simon & Schuster to generate interest in space among today’s younger children. -

A Mercury Astronaut, Spacewalker and Rookie 25 January 2017, by Marcia Dunn

Apollo 1's crew: a Mercury astronaut, spacewalker and rookie 25 January 2017, by Marcia Dunn Mercury capsule, the Liberty Bell 7. The hatch to the capsule prematurely blew off at splashdown on July 21, 1961. Grissom was pulled to safety, but his spacecraft sank. Next came Gemini. NASA assigned Grissom as commander of the first Gemini flight in 1965, and he good-naturedly picked Molly Brown as the name of the spacecraft after the Broadway musical "The Unsinkable Molly Brown." He was an Air Force test pilot before becoming an astronaut and his two sons ended up in aviation. Scott retired several years ago as a FedEx pilot, while younger Mark is an air traffic controller in Oklahoma. Their mother, Betty, still lives in Houston. This undated photo made available by NASA shows the Apollo 1 crew, from left, Edward H. White II, Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, and Roger B. Chaffee. On Jan. 27, Scott recalls how his father loved hunting, fishing, 1967, a flash fire erupted inside their capsule during a skiing and racing boats and cars. "To young boys, countdown rehearsal, with the astronauts atop the rocket all that stuff is golden," he says. at Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 34. All three were killed. (NASA via AP) ___ EDWARD WHITE II The three astronauts killed 50 years ago in the first White, 36, made history in 1965 as America's first U.S. space tragedy represented NASA's finest: the spacewalker. second American to fly in space, the first U.S. spacewalker and the trusted rookie. -

Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 6-2013 The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress Andrew Follett College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Follett, Andrew, "The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 584. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/584 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Government from The College of William and Mary by Andrew Follett Accepted for . John Gilmour, Director . Sophia Hart . Rowan Lockwood Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2013 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 3 Part 1: Introduction and Background 4 Pre Soviet Collapse: Early American Failures in Space 13 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Successful Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo Programs 17 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Quasi-Successful Shuttle Program 22 Part 2: The Thin Years, Repeated Failure in NASA in the Post-Soviet Era 27 The Failure of the Space Exploration Initiative 28 The Failed Vision for Space Exploration 30 The Success of Unmanned Space Flight 32 Part 3: Why NASA Fails 37 Part 4: Putting this to the Test 87 Part 5: Changing the Method. -

2008 NATIONAL SPACE TROPHY RECIPIENT - Eugene Andrew Cernan Rotary National Award for Space Achievement

2008 NATIONAL SPACE TROPHY RECIPIENT - Eugene Andrew Cernan Rotary National Award for Space Achievement he Rotary Na- ing at the U.S. Naval Post Graduate School. Their daughter Ttional Award for Tracy was born in March 1963. A few months later, he got a Space Achievement call asking if he’d volunteer for the astronaut program. “Well, (RNASA) Founda- yes sir!” Cernan responded. “Not only that, sir, but hell, yes! tion recognizes retired Sir!” (ibid, 53). He finished his degree and reported to Johnson Navy Captain Eugene Space Center as one of 14 new astronauts. Andrew Cernan with Cernan’s first mission, Gemini 9, launched on June 3, the 2008 National 1966. The flight required the launch of a rendezvous target fol- Space Trophy “for lowed by the separate launch of the crew. The crew performed outstanding achieve- the rendezvous in record time. But docking was not possible ments as an astronaut; because the nose shroud remained attached. Commander Tom second American to Stafford (1930--) radioed Houston, “We have a weird-looking walk in space; crew machine up here. It looks like an angry alligator” (ibid, 122). member on second Nevertheless, the crew successfully demonstrated multiple flight to the moon; rendezvous techniques. commander of the last At an altitude of 161 miles; Cernan became the second landing on the moon; American to walk in space. “I grabbed the edges of the hatch Eugene Andrew Cernan. and as an advocate for and climbed out of my hole until I stood on my seat.” He (Photo courtesy of The Cernan space exploration and Corporation) education.” The 2007 Trophy winner and former Flight Director Gene Kranz said, “I had the privilege of launching Cernan on his first mission into space and again at the beginning of his journey on Apollo 17. -

The Turtle Club

The Turtle Club The Turtle Club was dreamed up by test pilots during WWII, the Interstellar Association of Turtles believes that you never get anywhere in life without sticking your neck out. When asked,” Are you a Turtle?” Shepard leads you must answer with the password in full no matter the Corvette how embarassing or inappropriate the timing is, or and Astronaut you forfeit a beverage of their choice. parade, Coca Beach, FL. To become a part of the time honored tradition, you must be 18 years of age or older and be approved by the Imperial Potentate or High Potentate. Memebership cards will be individually signed by Wally Schirra and Schirra rides his Sigma 7 Ed Buckbee. A limited number of memberships are Mercury available. Apply today by filling out the order form spacecraft. below or by visiting www.apogee.com and follow the prompts to be a card carrying member of the Turtle Club! A portion of the monies raised by the Turtle Club Membership Drive will be donated to the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation and Space Camp Scholarships. Turtle Club co-founder Shepard, High Potentate Buckbee and Imeperial Potentate and co-founder Schirra enjoy a gotcha! Order your copy today of The Real Space Cowboys along with your Turtle Club Membership _______________________________________________ Name _______________________________________________ Address _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ City ___________________________ __________________ State Zip _______________________________________________ email ______________________ _____ __________________ Phone Age Birthdate You must be 18 years of age or older to become a member of the Turtle Club. __ No. of books @ $23.95 ______ Available Spring 2005 __ No. -

Apollo 11 Astronaut Neil Armstrong Broadcast from the Moon (July 21, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

Apollo 11 Astronaut Neil Armstrong Broadcast from the Moon (July 21, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell “One small step for…” Though no American has stepped onto the surface of the moon since 1972, the exiting of the Earth’s atmosphere today is almost commonplace. Once covered live over all TV and radio networks, increasingly US space launches have been relegated to a fleeting mention on the nightly news, if mentioned at all. But there was a time when leaving the planet got the full attention it deserved. Certainly it did in July of 1969 when an American man, Neil Armstrong, became the first human being to ever step foot on the moon’s surface. The pictures he took and the reports he sent back to Earth stopped the world in its tracks, especially his eloquent opening salvo which became as famous and as known to most citizens as any words ever spoken. The mid-1969 mission of NASA’s Apollo 11 mission became the defining moment of the US- USSR “Space Race” usually dated as the period between 1957 and 1975 when the world’s two superpowers were competing to top each other in technological advances and scientific knowledge (and bragging rights) related to, truly, the “final frontier.” There were three astronauts on the Apollo 11 spacecraft, the US’s fifth manned spaced mission, and the third lunar mission of the Apollo program. They were: Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins. The trio was launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida on July 16, 1969 at 1:32pm. -

For Further Information, Contact John T. Colby Jr., Publisher at [email protected]

For further information, contact John T. Colby Jr., Publisher at [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New York, NY – September 28, 2018 – Walter Cunningham, lunar module pilot on the Apollo 7 mission, fighter pilot, physicist, and author of iBooks’s All-American Boys will be inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame held in the National Building Museum in Washington D.C. He was NASA's third civilian astronaut (after Neil Armstrong and Elliot See). Cunningham received his B.A. with honors in 1960, and his M.A. with distinction in 1961, both in physics, from the University of California, Los Angeles. He completed all requirements save for the dissertation for a Ph.D. in physics at UCLA during his time at RAND Corporation, where he spent three years prior his NASA selection. Cunningham during the Apollo 7 mission In October 1963, Cunningham was one of the third group of astronauts selected by NASA. On October 11, 1968, he occupied the Lunar Module Pilot seat for the eleven-day flight of Apollo 7, the first launch of a manned Apollo mission. The flight carried no Lunar Module and Cunningham was responsible for all spacecraft systems except launch and navigation. The crew kept busy with myriad system tests and successfully completed test firing of the service-module- engine ignition and measuring the accuracy of the spacecraft systems. Schirra, with a cold, ran afoul of NASA management during the flight, but Cunningham went on to head up the Skylab Branch of the Astronaut Office and left NASA in 1971. He has accumulated more than 4,500 hours of flying time, including more than 3,400 in jet aircraft and 263 hours in space. -

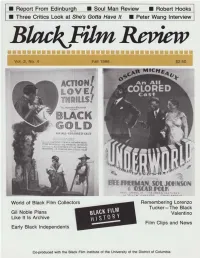

Report from Edinbur H • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview

Report From Edinbur h • Soul Man Review • Robert Hooks Three Critics Look at She's Gotta Have It • Peter Wang Interview World of Black Film Collectors Remembering Lorenzo Tucker- The Black. Gil Noble Plans Valentino Like It Is Archive Film Clips and News Early Black Independents Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Vol. 2, No. 4/Fa111986 'Peter Wang Breaks Cultural Barriers Black Film Review by Pat Aufderheide 10 SSt., NW An Interview with the director of A Great Wall p. 6 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 745-0455 Remembering lorenzo Tucker Editor and Publisher by Roy Campanella, II David Nicholson A personal reminiscence of one of the earliest stars of black film. ... p. 9 Consulting Editor Quick Takes From Edinburgh Tony Gittens by Clyde Taylor (Black Film Institute) Filmmakers debated an and aesthetics at the Edinburgh Festival p. 10 Associate EditorI Film Critic Anhur Johnson Film as a Force for Social Change Associate Editors by Charles Burnett Pat Aufderheide; Keith Boseman; Excerpts from a paper delivered at Edinburgh p. 12 Mark A. Reid; Saundra Sharp; A. Jacquie Taliaferro; Clyde Taylor Culture of Resistance Contributing Editors Excerpts from a paper p. 14 Bill Alexander; Carroll Parrott Special Section: Black Film History Blue; Roy Campanella, II; Darcy Collector's Dreams Demarco; Theresa furd; Karen by Saundra Sharp Jaehne; Phyllis Klotman; Paula Black film collectors seek to reclaim pieces of lost heritage p. 16 Matabane; Spencer Moon; An drew Szanton; Stan West. With a repon on effons to establish the Like It Is archive p.