One Century in the University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Complutense De Madrid Facultad De Geografía E Historia Conformación Y Desarrollo Del Sistema Parvulario Chileno

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE GEOGRAFÍA E HISTORIA CONFORMACIÓN Y DESARROLLO DEL SISTEMA PARVULARIO CHILENO, 1905-1973: UN CAMINO PROFESIONAL CONDICIONADO POR EL GÉNERO MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Paloma Abett de la Torre Díaz Bajo la dirección de la doctora María Teresa Nava Rodríguez MADRID, 2013 © Paloma Abett de la Torre Díaz, 2013 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Facultad de Geografía e Historia DOCTORADO INTERUNIVERSITARIO LA PERSPECTIVA FEMINISTA COMO TEORÍA CRÍTICA Conformación y Desarrollo del Sistema Parvulario Chileno 1905-1973: Un camino profesional condicionado por el género Autora: Paloma Abett de la Torre Díaz Tesis Doctoral dirigida por: María Teresa Nava Rodríguez [2] Agradecimientos La posibilidad de desarrollar mis estudios doctorales en España, ha sido obra de personas e instituciones a las cuales quiero reconocer. En primer lugar, agradezco de manera especial a la Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica de Chile (CONICYT) por financiar, a través de una beca de estudios doctorales en el extranjero, mi formación académica en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, y en ese contexto, a mis profesoras del Doctorado, especialmente a mi tutora María Teresa Nava Rodríguez, quien no sólo dirigió este trabajo, sino que además ha sido atenta y generosa frente a mis constantes requerimientos de toda índole. En segundo lugar, quisiera agradecer a la Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano por facilitarme las condiciones para realizar mis estudios; a mis compañeros Felipe y María José que me ayudaron en mis quehaceres, y muy especialmente, a mi amiga y compañera Beatriz, no sólo por el apoyo académico sino también por nuestras largas conversaciones y su férrea compañía. -

Clara Campoamor. El Voto Femenino Y Yo

1 CLARA CAMPOAMOR EN BUSCA DE LA IGUALDAD “ Y para llegar al final hay que cruzar por el principio; a veces bajo lluvia de piedras.” Clara Campoamor. El voto femenino y yo. NEUS SAMBLANCAT MIRANDA ( GEXEL-CEFID) Palabras como libertad, dignidad, coraje, igualdad jurídica o libre elección parecerían hoy menos transparentes si no hubiera existido una mujer como Clara Campoamor Rodríguez. Una mujer fuerte, de cara aniñada, de grandes ojos negros y espesas cejas, extrovertida, generosa, alegre. Nació en Madrid, el día 12 de febrero de 1888, a las diez de la mañana.2 Su partida de nacimiento, escrita a modo de crónica, da cuenta del origen de sus padres: Manuel Campoamor Martínez, natural de Santoña (Santander) y Pilar Rodríguez Martínez, natural de Madrid. Sus abuelos paternos, Juan Antonio Campoamor y Nicolasa Martínez, procedían de las localidades de San Bartolomé de Otur (Oviedo) y de Argoños (Santander). Sus abuelos maternos, Silvestre Rodríguez y Clara Martínez, eran naturales de Esquivias (Toledo) y de Arganda del Rey (Madrid).3 Clara Campoamor no lo tuvo fácil en la vida: quedó huérfana de padre muy pronto.4 Para ayudar a su madre y 1 Este texto es la introducción revisada y ampliada a mi edición de la obra de Clara Campoamor, La revolución española vista por una republicana ( Bellaterra, Barcelona, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Servei de Publicacions, 2002, 212 pp.). En 2002, el título de la introducción era: Clara Campoamor, pionera de la modernidad. Las páginas citadas de la obra pertenecen a dicha edición. El estudio se publica con la autorización de la Asociación Clara Campoamor. -

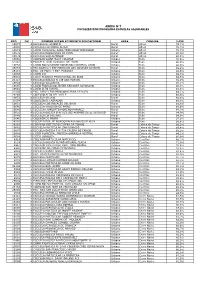

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

Clara Campoamor, Paulina Luisi Y La Guerra Civil Española

Eugenia Scarzanella Amistad y diferencias políticas: Clara Campoamor, Paulina Luisi y la Guerra Civil española [...] reciba estas palabras mas como las de una madre al hijo prodigo, como el consejo sano de quien la quiere y desea tenderle la mano viendo venir sobre Ud males mayores que su estado de ánimo no le permite apreciar con la debida claridad, de quien desea con el corazon salvarla de mayores errores (carta de Paulina Luisi a Clara Campoamor, Monte- video 5 de diciembre de 1937). Un afecto debe acusarse de todo menos de haber callado cuando debía hablar (carta de Clara Campoamor a Paulina Luisi, Lausanne, 30 de di- ciembre de 1937).* 1. Introducción En el archivo literario de la Biblioteca Nacional de Montevideo se conserva, entre las cartas de Paulina Luisi, su correspondencia con Clara Campoamor. La componen 41 cartas, todas inéditas, 39 de Clara a Paulina y dos de Paulina a Clara. El epistolario abarca los años que van desde 1920 hasta 1937.1 Mi ensayo se centra sobre todo en las siete cartas (dos de Paulina y cinco de Clara), escritas en 1937, en vísperas del exilio de Clara en América Latina. A diferencia de las anteriores no se ocupan de su actividad común en las organizaciones femeninas internacionales y en la Sociedad de las Naciones, terreno en el que se había consolidado la amistad entre la feminista uruguaya y la feminista española. Tema central de estas dramáticas cartas, que ates- tiguan una incomprensión profunda entre las dos amigas y anuncian la amarga ruptura de la relación, es la situación política española. -

Spanish Women in Defense of the 2Nd Republic

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, vol.5 - nº3 (2011), 025-044 1646-5954/ERC123483/2011 025 Also in the newspapers: Spanish women in defense of the 2nd Republic Matilde Eiroa San Francisco*, José Mª Sanmartí Roset** * Facultad de Humanidades, Comunicación y Documentación Universidad Carlos III de Madrid ** Facultad de Humanidades, Comunicación y Documentación Universidad Carlos III de Madrid Abstract This article analyzes the journalistic facet of a generation of Spanish women who were formed in the 1920s and 1930s; women who had an important public presence in the Republican years due to their struggle for freedoms and social progress. In order to gain a clearer understanding of this reality, we used a deductive and comparative perspective in our research. This perspective itself forms part of the theoretical framework of the history of communication and the new political history- two conceptual proposals which provide us with the opportunity to examine the internal factors in women’s history. Our main aim in the article has been to recover the informative output that these women built up throughout the leading communication media at the time; an output which perhaps constitutes the least known aspect of a feminist collective which was so prominent in political or literary circles. Keywords: Women, Spain, Civil War, Journalism, 2nd Republic. Introduction The historiography produced on the subject of 20th century Spain already includes a number of studies that have recovered the names of women who contributed in different ways to the political, social, economic and cultural evolution of the country. This is particularly the case in the periods of the Second Republic (1931-1939) or the Civil War (1936-1939), where research has used primary and secondary sources to reconstruct the histories of the most relevant of these women. -

NOTICIAS Tesis Doctoral, Aunque Ahora Matilde Eiroa Se Ha Centrado Más En Su Labor Diplomática Y Periodística Durante La Segunda República Y La Guerra Civil 2

nooticiasticias EIROA SAN FRANCISCO, Matilde: Isabel de Palencia. Diplomacia, pe- riodismo y militancia al servicio de la República, Málaga, Universidad de Málaga, 2014, 310 págs. Este libro, fruto de una intensa investigación por diversos archivos y centros documentales, recoge la trayectoria de una mujer apasionante como Isabel Oyarzábal. La profesora Matilde Eiroa nos traza los entresijos de su peripecia vital, centrándose especialmente en los años treinta y, sobre todo, durante la guerra civil, cuando llega a ser diplomática al servicio de la República. Prueba del interés y de la calidad de este trabajo queda demostrada con el reconocimiento que supone haber logrado el Premio Victoria Kent de la Universidad de Málaga en su vigésimo tercera edición, que afortunadamente conllevaba la publicación del texto para que todos podamos conocer la historia de esta mujer. Últimamente han proliferado estudios sobre mujeres republicanas, anó- nimas y famosas, debido a varias razones 1 . En primer lugar al interés por rescatar todo aquello que realizaron las vencidas, tantos años ocultos por la dictadura, aparte del castigo y de la persecución que implicaron para las protagonistas. Pero, sobre todo, debido al papel más relevante que tuvieron las republicanas respecto a las franquistas, en relación con los discursos emancipadores e igualitarios que se desarrollaron entre las diversas fuerzas políticas y sindicales que contribuyeron al esfuerzo de guerra de la República. Sobre la periodista y escritora socialista Isabel Oyarzábal de Palen- cia, que se convirtió en la primera mujer embajadora de España en plena contienda, en 2009 apareció la biografía de Olga Paz Torres, fruto de una 1. -

Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona 1898–1937

Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona 1898–1937 This is a study of social protest and repression in one of the twentieth century’s most important revolutionary hotspots. It explains why Barcelona became the undisputed capital of the European anarchist movement and explores the sources of anarchist power in the city. It also places Barcelona at the centre of Spain’s economic, social, cultural and political life between 1898 and 1937. During this period, a range of social groups, movements and institutions competed with one another to impose their own political and urban projects on the city: the central authorities struggled to retain control of Spain’s most unruly city; nationalist groups hoped to create the capital of Catalonia; local industrialists attempted to erect a modern industrial city; the urban middle classes planned to democratise the city; and meanwhile, the anarchists sought to liberate the city’s workers from oppression and exploitation. This resulted in a myriad of frequently violent conflicts for control of the city, both before and during the civil war. This is a work of great importance in the field of contemporary Spanish history and fills a significant gap in the current literature. Chris Ealham is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History, Lancaster University. He is co-editor of The Splintering of Spain: Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War. His work focuses on labour and social protest in Spain, and he is currently working on a history of urban conflict in 1930s Spain. Routledge/Cañada Blanch Studies -

Clara Campoamor: Cartas Desde El Exilio

Clara Campoamor: cartas desde el exilio Neus Samblancat Miranda UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BARCELONA CADA VEZ MÁS EN los últimos años la bibliografía sobre la literatura del exilio español de 1939 se nutre de estudios1-algunos de ellos con perspectiva de género-que analizan la actividad literaria, jurídica o social de una brillante generación de mujeres nacidas a finales del siglo XIX o comienzos del XX que irrumpieron con fuerza en los años de la 11 República. Entre ellas, Carmen de Burgos, Carmen Baroja, María Goyri, Isabel Oyarzábal, María de Maeztu, María Lejárraga, Victoria Kent, Zenobia Camprubí, Matilde Huici, Concha Méndez, Emestina de Champurcín, Rosa Chacel, Constancia de la Mora, María Teresa León, Maruja Mallo, Federica Montseny o Ana María Martínez Sagi. Todas formaron parte de ese grupo de mujeres modemas--con estudios superiores algunas de ellas, reunidas otras en tomo al Lyceum Club-que, desde las primeras décadas del siglo XX, lucharon por su independencia económica y por el acceso a todas las profesiones «en igual medida y aptitud que el varón,»2 en palabras de Clara Campoamor. Quien con voz profética auguró en su conferencia impartida en la Academia de Jurisprudencia de Madrid el 13 de abril de 1925: El siglo XX será, no lo dudéis, el de la emancipación femenina[ ... ] Es imposible imaginar a una mujer de los tiempos modernos que, como principio básico de individualidad, no aspire a la libertad.3 1 V. Antonina Rodrigo, Mujer y exilio, 1939, Prólogo de M. Vázquez Montalbán, Madrid: Compañía Literaria, 1999, pp.405; Alicia Alted, «El exilio republicano español de 1939 desde la perspectiva de las mujeres,» Arenal. -

Material Didáctico Para Visitas Escolares (ESO/Bachillerato)

Material didáctico para visitas escolares (ESO/Bachillerato) Materiales para el profesor INTRODUCCIÓN. RESUMEN DE LOS CONTENIDOS DE LA EXPOSICIÓN La trayectoria de la Residencia de Señoritas se vincula de manera directa con el notable cambio en la situación social de las mujeres en España durante el primer tercio del siglo XX. Las primeras iniciativas concretas en favor de la educación de la mujer se debieron a Fernando de Castro, fundador de la Asociación para la Enseñanza de la Mujer en 1870. Continuando la labor iniciada por Castro, Francisco Giner de los Ríos y los hombres y mujeres de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE), que mantenía entre sus principios el de la coeducación, prosiguieron la tarea de la defensa de los derechos de la mujer, comenzando por el de una educación en igualdad. La Junta para Ampliación de Estudios (JAE), creada en 1907, presidida por Santiago Ramón y Cajal y cuyo secretario fue José Castillejo, se encargó de llevar a la práctica el proyecto de modernización de la sociedad española a través de la educación que inspiró la ILE. En 1910, la JAE funda la Residencia de Estudiantes, que preside Alberto Jiménez Fraud, y en 1915 extiende esa experiencia a la educación de la mujer con la creación del grupo femenino de la Residencia de Estudiantes, la Residencia de Señoritas, para el que designa a María de Maeztu como directora. Victoria Kent, Matilde Huici, Delhy Tejero o Josefina Carabias estuvieron entre las residentes más destacadas. María Goyri, María Zambrano, Victorina Durán o Maruja Mallo formaron parte de su profesorado. Zenobia Camprubí, Gabriela Mistral, Victoria Ocampo, María Martínez Sierra o Clara Campoamor participaron en sus actividades. -

Revista De Estudios Penitenciarios. N. 257 (2014)

Revista de Estudios Penitenciarios N.º 257 Año 2014 CONSEJO DE REDACCIÓN Presidente D. Ángel Yuste Castillejo Secretario General de Instituciones Penitenciarias Vicepresidente D. Javier Nistal Burón Subdirector General de Tratamiento y Gestión Penitenciaria Vocales D. Carlos García Valdés Catedrático de Derecho Penal D. Emilio Tavera Benito Jurista Criminólogo D. Abel Téllez Aguilera Magistrado y Doctor en Derecho D. José Luis de Castro Antonio Magistrado del Juzgado Central de Vigilancia Penitenciaria y de Menores de Madrid D.ª Miriam Tapia Ortiz Subdirectora General de Penas y Medidas Alternativas D. José María Pérez Peña Subdirector General de la Inspección Penitenciaria D. José Manuel Arroyo Cobo Subdirector General de Coordinación de Sanidad Penitenciaria D.ª María Yela García Jefa de Servicio de la Subdirección General de Tratamiento y Gestión Penitenciaria D.ª Francesca Melis Pont Técnico Superior de la Subdirección General de Tratamiento y Gestión Penitenciaria D.ª Zoraida Estepa Carmona Directora de Programas del Centro de Estudios Penitenciarios Secretaria D.ª Laura Lledot Leira Jefa del Servicio de Estudios y Documentación La responsabilidad por las opiniones emitidas en esta publicación corresponde exclusivamente a los autores de las mismas. En esta publicación se ha utilizado papel reciclado libre de cloro de acuerdo con los criterios medioambientales de la contratación pública Catálogo de publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado http://publicacionesoficiales.boe.es Edita: Ministerio del Interior. Secretaría General Técnica. NIPO (ed. en línea): 126-14-066-4 NIPO (ed. papel): 126-14-067-X ISSN: 0210-6035 Depósito legal: M-2306-1958 Imprime: Entidad Estatal de Derecho Público Trabajo Penitenciario y Formación para el Empleo Imprime: Taller de Artes Gráficas del Centro Penitenciario de Madrid III (Valdemoro) SUMARIO Págs. -

First Steps Towards Equality: Higher Education for Women in Spain (1910-1936)

First Steps towards Equality: Higher Education for Women in Spain (1910-1936) Abstract A social and intellectual conflict was waged between Catholics and secularists in Spain at the turn of the 20th century. In 1910, following forty long years of struggle, women were finally granted access to the university system. This fact positioned women at the heart of the dispute between the two competing schools of thought, both of which supported the intellectual development of women as an essential part of their respective educational projects for political and social renewal. Nonetheless, the vision of women held on both sides fell far short of recognizing the suitability of women for participation in public life. On the basis of a close reading of the research literature in this field (84 works), this article shows that the educational projects advanced by both groups were remarkably similar, given that each drew on similar prejudices regarding women. Keywords: Women, University, Public Sphere, Spain 1910–1936 Introduction The chronological coordinates of this paper are 1910, the year in which Spanish women were granted access to the higher education system, and 1936, the year in which the Spanish Civil War broke out. The Civil War was a watershed in contemporary Spanish history, marking a definitive before and after: any development at the time was crudely interrupted, and if it resurfaced following the conflict, it did so in a radically different way. No sense of clear continuity may be discerned. Each of the two prevailing schools of thought, which might be referred to in broad terms as Catholic and secularist, made a distinctive contribution to the area of higher education for women. -

Clara Campoamor

Clara Campoamor Clara Campoamor (1888, Espanya – 1972, Suïssa) Clara Campoamor neix a Madrid el 1888. El 1914, després d’aconseguir una oposició, es converteix en professora d'adults del Ministeri d'Instrucció Pública. Com que no tenia el batxillerat, però, només pot impartir classes de taquigrafia i mecanografia. Això la motiva a seguir estudiant i ho compagina amb les seves feines de mecanògrafa al Ministeri i de secretària al diari La Tribuna. El 1923 participa en un cicle sobre feminisme organitzat per la Joventut Universitària Femenina, on comença a desenvolupar els seus idearis sobre el dret de les dones a la igualtat. El 1924, als 36 anys, es llicencia en dret. Campoamor va ser la primera dona que va intervenir davant del Tribunal Suprem i que va desenvolupar treballs de jurisprudència sobre qüestions relati- ves als drets de la situació jurídica de les dones a l’Estat espanyol. El 1928 crea la Federació Internacional de Dones de Carreres Jurídiques, on treballa al costat de Victoria Kent i Matilde Huici al Tribunal de Menors. Amb Azaña forma part de la junta directiva de l'Ateneu de Madrid i es declara republicana. En els darrers anys de la dictadura de Primo de Rivera, col•labora al diari La Libertad, on presenta i analitza la vida de dones en una secció pròpia titulada "Mujeres de hoy". Després de la dictadura, entra a formar part del Partit Radical i es presenta a les eleccions del 1931 per a les Corts Constituents de la Segona República, i hi obté un escó com a diputada per Madrid.