Seduction Incarnate: Pre-Production Code Hollywood and Possessive Spectatorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2016 Calendar

December Calendar Exhibits In the Karen and Ed Adler Gallery 7 Wednesday 13 Tuesday 19 Monday 27 Tuesday TIMNA TARR. Contemporary quilting. A BOB DYLAN SOUNDSWAP. An eve- HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free AFTERNOON ON BROADWAY. Guys and “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” (2015- December 1 through January 2. ning of clips of Nobel laureate Bob blood pressure screening conducted Dolls (1950) remains one of the great- 108 min.). Writer/director Matt Brown Dylan. 7:30 p.m. by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. est musical comedies. Frank Loesser’s adapted Robert Kanigel’s book about music and lyrics find a perfect match pioneering Indian mathematician Registrations “THE DRIFTLESS AREA” (2015-96 min.). in Damon Runyon-esque characters Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) and Bartender Pierre (Anton Yelchin) re- and a New York City that only exists in his friendship with his mentor, Profes- In progress turns to his hometown after his parents fantasy. Professor James Kolb discusses sor G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons). Stephen 8 Thursday die, and finds himself in a dangerous the show and plays such unforgettable Fry co-stars as Sir Francis Spring, and Resume Workshop................December 3 situation involving mysterious Stella songs as “A Bushel and a Peck,” “Luck Be Jeremy Northam portrays Bertrand DIRECTOR’S CUT. Film expert John Bos- Entrepreneurs Workshop...December 3 (Zoe Deschanel) and violent crimi- a Lady” and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ Russell. 7:30 p.m. co will screen and discuss Woody Al- Financial Checklist.............December 12 nal Shane (John Hawkes). Directed by the Boat.” 3 p.m. -

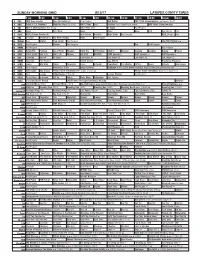

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

9781474451062 - Chapter 1.Pdf

Produced by Irving Thalberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd i 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Produced by Irving Thalberg Theory of Studio-Era Filmmaking Ana Salzberg 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iiiiii 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Ana Salzberg, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Monotype Ehrhardt by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5104 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5106 2 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5107 9 (epub) The right of Ana Salzberg to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66311_Salzberg.indd311_Salzberg.indd iivv 221/04/201/04/20 66:34:34 PPMM Contents Acknowledgments vi 1 Opening Credits 1 2 Oblique Casting and Early MGM 25 3 One Great Scene: Thalberg’s Silent Spectacles 48 4 Entertainment Value and Sound Cinema -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman in July

CORE © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016. This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyeditMetadata, version of citation a chapter and published similar papers in at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Lasting Screen Stars: Images that Fade and Personas that Endure. The final authenticated version is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40733-7_6 ‘What Price Widowhood?’: The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman In July 1934, Photoplay magazine featured an article entitled ‘The Real First Lady of Film’, introducing the piece as follows: The First Lady of the Screen – there can be only one – who is she? Her name is not Greta Garbo, or Katharine Hepburn, not Joan Crawford, Ruth Chatterton, Janet Gaynor or Ann Harding. It’s Norma Shearer (p. 28). Originally from Montréal, Canada, Norma Shearer signed her first MGM contract at age twenty. By twenty-five, she had married its most promising producer, Irving Thalberg, and by thirty-five, she had been widowed through the latter’s untimely death, ultimately retiring from the screen forever at forty. During the intervening twenty years, Shearer won one Academy Award and was nominated for five more, built up a dedicated, international fan base with an active fan club, was consistently featured in fan magazines, and starred in popular and critically acclaimed films throughout the silent, pre-Code and post-Code eras. Shearer was, at the height of her fame, an institution; unfortunately, her career is rarely as well-remembered as those of her contemporaries – including many of the stars named above. -

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Under Contract with the United States Department of Energy

,... Operated by Universities Research Association Inc. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Under Contract with the United States Department of Energy Vol. 3, No. 33 August 14, 1980 COMPUTING DEPARTMENT REORGANIZES The Computing Department has been reorganized to better serve the scientific community and to take advantage of new technologies. One of the major changes is that PREP-- acronym for Physics Research Equipment Pool-- and Instrument Repair have been transferred from Research Services to the Computing De- partment. Familiar people with new re- sponsibilities include Jeff Appel, who is now associate head of the Computing Depart- ment and head of the new Data Acquisition Group in the Department. The Data Acquis- ition Group includes both the hardware and software efforts associated with gathering data for the high energy physics experi- ments at the Laboratory. (L-R) Jeff Appel, Al Brenner and Art Neubauer. Brenner said, "The meeting Appel, a physicist, joined the was held in an area containing a most Department from the Energy Saver Division. stable and valued computing element," Art Neubauer, who was in charge of referring, of course, to the abacus FREP and Instrument Repair with Research overhead. "It's maintenance free and Services, is now head of the Hardware Group works," he added. which includes PREP, Instrument Repair and Mini-Computer Maintenance, headed by Chuck Andrle and Rich Knowles, respectively. Andrle was with Research Services, and Knowles was already with the Computing Department. "In their new positions, Appel, Neubauer, Andrle and Knowles have increased responsibilities and challenges," said Al Brenner, head of the Computing Department. "We are pleased to have them in these key reorganization positions." For the time being, however, PREP and Instrument Repair will remain physically on the 14th floor of the Central Laboratory. -

Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period Ending January 10, 2012

Walking Box Ranch Public Lands Institute 1-10-2012 Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending January 10, 2012 Margaret N. Rees University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, and the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Repository Citation Rees, M. N. (2012). Walking Box Ranch Planning and Design Quarterly Progress Report: Period ending January 10, 2012. 1-115. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/pli_walking_box_ranch/30 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Walking Box Ranch by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT University of Nevada, Las Vegas Period Covering October 11, 2010 – January 10, 2012 Financial Assistance Agreement #FAA080094 Planning and Design of the Walking Box Ranch Property Executive Summary UNLV’s President Smatresk has reiterated his commitment to the WBR project and has further committed full funding for IT and security costs. -

“A Grievous Necessity”: the Subject of Marriage in Transatlantic Modern Women’S Novels: Woolf, Rhys, Fauset, Larsen, and Hurston

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A GRIEVOUS NECESSITY”: THE SUBJECT OF MARRIAGE IN TRANSATLANTIC MODERN WOMEN’S NOVELS: WOOLF, RHYS, FAUSET, LARSEN, AND HURSTON A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kristin Kommers Czarnecki B.A., University of Notre Dame 1991 M.A., Northwestern University 1997 Committee Chair: Arlene Elder ABSTRACT “A GRIEVOUS NECESSITY”: THE SUBJECT OF MARRIAGE IN TRANSATLANTIC MODERN WOMEN’S NOVELS: WOOLF, RHYS, FAUSET, LARSEN, AND HURSTON My dissertation analyzes modern women’s novels that interrogate the role of marriage in the construction of female identity. Mapping the character of Clarissa in The Voyage Out (1915), “Mrs. Dalloway’s Party” (1923), and primarily Mrs. Dalloway (1925), I highlight Woolf’s conviction that negotiating modernity requires an exploratory yet protected consciousness for married women. Rhys’s early novels, Quartet (1929), After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie (1931), Voyage in the Dark (1934), and Good Morning, Midnight (1939), portray women excluded from the rite of marriage in British society. Unable to counter oppressive Victorian mores, her heroines invert the modernist impulse to “make it new” and face immutability instead, contrasting with the enforced multiplicity of identity endured by women of color in Fauset’s Plum Bun (1929) and Larsen’s Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929). -

Cinema and the Modern Woman 3

CINEMA AND THE 31 MODERN WOMAN Veronica Pravadelli In American cinema of the 1930s the image of the modern woman and the trajectory of female desire present two different models. Between the end of the 1920s and the early 1930s, American cinema continued to focus on the image of the young, self- assertive, and sexy woman in her multiple facets: Working girls, gold diggers, flappers, show girls, and kept women inundated the talkies and perpetuated the cult of New Womanhood that emerged in the early years of the century. This tendency would wane as the decade progressed. From about the mid- - 1930s, the dominant narrative of female desire was tuned to the formation of the couple and to marriage while the figure of the emancipated woman became marginal. In this process the representation of class rise and upward mobility were also questioned and the heroine’s social aspirations were more often thwarted than supported. One need only compare Baby Face (1933) and Stella Dallas (1937), both starring Barbara Stanwyck in the leading role, to realize how the convergence between gender and class changed dramatically in just a few years. In the second half of the 1930s, only the upper- class protagonists of screwball comedy enjoyed sexual freedom and independence while working- class women were denied both upward mobility and gender equality. This shift in the representation of gender identity was matched by a concomi- tant transformation in film style. In the early 1930s, American cinema extended the use of visual techniques developed during the silent period that we may consider in light of the “cinema of attractions.” While such a cinema is overtly narrative, at specific moments (especially, but not only, in the opening episode), the film avoids both narrative articulation and dialogue and communicates merely through visual devices. -

Cireen RASH to HOE for EUROPE at DAWN

- t.- ■; ,--■ -,V / ' .■_-’'■ ^..... .. ■* ,■•**./-.•.' - . • • ................... • . ' ....... , >'.'; •:.■■■;•' • f I 't' » > •*jr........ • NET PtlBSB RUN AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION for the Mqiith of April, 1029 - 5344 MuBbcn of th« Aaeit Bareav ef CIrealatioaa _ VOL. X L in ., NO. 186. (Chuelfled AdvertUlng on Page 12) SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, MAY 22, 1929. FOURTEEN PAGES PRICE THREE CENTS ♦- BRAKES F U m t HOLD SUSPECT TO START FOR ROME TOMORROW AUTO CRUSHES FOUND NEAR CiREEN RASH TO HOE A P m R I A N M ORR^ PLACE FORI EUROPE AT DAWN ■ ■ ' ---------------------------------------- ----------------------- ■ - - ^ ---------- Mrs. Aibertma Peterson Ron Mexican Tries to Force His Gunmen Kill Sleuth Am erican Hyers,After Down by Car Whose Driv Way to CoL Lindbergh; Is 5*V*,•• Nsn er Saw Her Bnt Had No Unarmed But Placed in Hot On Their Trail Control of Vebicle. Jail for Safekeeping. Chicago, May 22.— GangsterAmurder of Scalise, Anselmi and row Unless Bad Weather murderers, fearing for their lives Guiuta and the shooting by kid naper extortionists of Policeman because the police trail bad become Mrs. Albertina M. Peterson, 56, North Haven. Me., May 22.— Roy Martin, ambushed and killed. Interfered— No Trans-At too “ hot” for them’, took matters wife of S. Emil Peterson of 25 While police and secret service men Sullivan had been badly beaten grilled a mysterious young man, into their hands here today and before be was killed. Both eyes Alton street, was very seriously in gave Detective Joseph Sullivan, ace were blackened, his clothing was in lantic Race as French jured at 4:35 yesterday afternoon arrested after attempting to force of detective bureau secret inves- | disarray and he had been struck on Center street when struck by an' his way to Col. -

2011 Schedule

2011 SCHEDULE Tuesday, February 1 6:00 AM Eskimo (’33) 8:00 AM Hide-Out (’34) 9:30 AM Manhattan Melodrama (’34) 11:15 AM The Thin Man (’34) 1:00 PM Citizen Kane (’41) 3:00 PM The Great Dictator (’40) 5:15 PM Richard III (‘55) 8:00 PM The Private Life of Henry VIII (’33) 10:00 PM A Man for All Seasons (’66) 12:15 AM Anne of the Thousand Days (’69) 2:45 AM Last Summer (’69) 4:30 AM Anthony Adverse (’36) Wednesday, February 2 7:00 AM The Great Waltz (’38) 8:45 AM The Little Foxes (’41) 11:00 AM Nicholas and Alexandra (’71) 2:15 PM The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (’68) 4:30 PM Lonelyhearts (’58) 6:15 PM The Moon is Blue (’53) 8:00 PM Five Easy Pieces (’70) 10:00 PM Terms of Endearment (’83) 12:30 AM Easy Rider (’69) 2:15 AM The Lost Detail (’73) 4:15 AM The Guardsman (’31) Thursday, February 3 6:00 AM Witness for the Prosecution (’57) 8:00 AM Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (’66) 10:30 AM Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (’67) 12:30 PM Johnny Belinda (’48) 2:30 PM For Whom the Bell Tolls (’43) 5:30 PM A Streetcar Named Desire (’51) 8:00 PM The Love Parade (’29) 10:00 PM All Quiet on the Western Front (’30) 12:30 AM The Big House (’30) 2:00 AM The Divorcee (’30) 3:30 AM Disraeli (’29) 5:00 AM Edward, My Son (’49) Friday, February 4 7:00 AM Separate Tables (’58) 9:00 AM The Sundowners (’60) 11:30 AM The Champ (’31) 1:00 PM Dr.