Scarface, Gatsby, and the American Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2016 Calendar

December Calendar Exhibits In the Karen and Ed Adler Gallery 7 Wednesday 13 Tuesday 19 Monday 27 Tuesday TIMNA TARR. Contemporary quilting. A BOB DYLAN SOUNDSWAP. An eve- HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free AFTERNOON ON BROADWAY. Guys and “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” (2015- December 1 through January 2. ning of clips of Nobel laureate Bob blood pressure screening conducted Dolls (1950) remains one of the great- 108 min.). Writer/director Matt Brown Dylan. 7:30 p.m. by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. est musical comedies. Frank Loesser’s adapted Robert Kanigel’s book about music and lyrics find a perfect match pioneering Indian mathematician Registrations “THE DRIFTLESS AREA” (2015-96 min.). in Damon Runyon-esque characters Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) and Bartender Pierre (Anton Yelchin) re- and a New York City that only exists in his friendship with his mentor, Profes- In progress turns to his hometown after his parents fantasy. Professor James Kolb discusses sor G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons). Stephen 8 Thursday die, and finds himself in a dangerous the show and plays such unforgettable Fry co-stars as Sir Francis Spring, and Resume Workshop................December 3 situation involving mysterious Stella songs as “A Bushel and a Peck,” “Luck Be Jeremy Northam portrays Bertrand DIRECTOR’S CUT. Film expert John Bos- Entrepreneurs Workshop...December 3 (Zoe Deschanel) and violent crimi- a Lady” and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ Russell. 7:30 p.m. co will screen and discuss Woody Al- Financial Checklist.............December 12 nal Shane (John Hawkes). Directed by the Boat.” 3 p.m. -

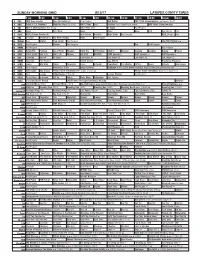

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

GAILY, GAILY the NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY's “In 1925, There

The one area where it succeeded perfectly was So, Rosenblum began refashioning the film, in its score by Henry Mancini. By this time, using a clever device of stock footage that Mancini was already a legend. After toiling in the would lead into the production footage, rear - GAILY, GAILY music department at Universal (the highlight of ranging and restructuring scenes, and spend - his tenure there would be Orson Welles’ Touch ing a year doing so – the result was stylish and Of Evil) , he hit it big, first with his TV score to visually interesting and it transformed the film THE NIGHT Peter Gunn – which not only provided that from disaster into a hit. THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S Blake Edwards series with its signature sound, but which also produced a best-selling album The score for Minsky’s was written by Charles on RCA – and then in a series of films for which Strouse, who’d already written several Broad - “In 1925, he provided amazing scores, one right after an - way shows, as well as the score for the film other – Breakfast At Tiffany’s, Charade, Hatari, Bonnie and Clyde . The lyrics were by Lee there was this real The Pink Panther, Days Of Wine and Roses , Adams, with whom Strouse had written the religious girl” and many others. Many of those films also pro - Broadway shows Bye Bye Birdie, All-American, duced best-selling albums. Mancini not only Golden Boy, It’s A Bird, It’s A Plane, It’s Super - knew how to score a film perfectly, but he was man and others. -

Nothing Sacred (United Artists Pressbook, 1937)

SEE THE BIG FIGHT! DAVID O. SELZNICK’S Sensational Technicolor Comedy NOTHING SACRED WITH CAROLE LOMBARD FREDRIC MARCH CHARLES WINNINCER WALTER CONNOLLY by the producer and director of "A Star is Born■ Directed by WILLIAM A. WELLMAN * Screen play by BEN HECHT * Released thru United Artists Coyrighted MCMXXXVII by United Artists Corporation, New York, N. Y. KNOCKOUT'- * IT'S & A KNOCKOUT TO^E^ ^&re With two great stars 1 about cAROLE {or you to talk, smg greatest comedy LOMBARD, at her top the crest ol pop- role. EREDWC MARC ^ ^ ^feer great ularity horn A s‘* ‘ cWSD.» The power oi triumph in -NOTHING SA oi yfillxanr Selznick production, h glowing beauty oi Wellman direction, combination ^ranced Technicolor {tn star ls . tS made a oi a ^ ““new 11t>en “^ ”«»•>- with selling angles- I KNOCKOUT TO SEE; » It pulls no P“che%afanXioustocount.Beveald laughs that come too to ot Carole Lomb^ mg the gorgeous, gold® the suave chmm ior the fast “JXighest powered rolejhrs oi Fredric March m the g ^ glamorous Jat star has ever had. It 9 J the scieen has great star st unusual story toeS production to th will come m on “IsOVEB:' FASHION PROMOTION ON “NOTHING SACHEH” 1AUNCHING a new type of style promotion on “The centrated in the leading style magazines and papers. And J Prisoner of Zenda,” Selznick International again local distributors of these garments will be well-equipped offers you this superior promotional effort on to go to town with you in a bang-up cooperative campaign “Nothing Sacred.” Through the agency of Lisbeth, on “Nothing Sacred.” In addition, cosmetic tie-ups are nationally famous stylist, the pick of the glamorous being made with one of the country’s leading beauticians. -

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films

Jean Harlow ~ 20 Films Harlean Harlow Carpenter - later Jean Harlow - was born in Kansas City, Missouri on 3 March 1911. After being signed by director Howard Hughes, Harlow's first major appearance was in Hell's Angels (1930), followed by a series of critically unsuccessful films, before signing with Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer in 1932. Harlow became a leading lady for MGM, starring in a string of hit films including Red Dust (1932), Dinner At Eight (1933), Reckless (1935) and Suzy (1936). Among her frequent co-stars were William Powell, Spencer Tracy and, in six films, Clark Gable. Harlow's popularity rivalled and soon surpassed that of her MGM colleagues Joan Crawford and Norma Shearer. By the late 1930s she had become one of the biggest movie stars in the world, often nicknamed "The Blonde Bombshell" and "The Platinum Blonde" and popular for her "Laughing Vamp" movie persona. She died of uraemic poisoning on 7 June 1937, at the age of 26, during the filming of Saratoga. The film was completed using doubles and released a little over a month after Harlow's death. In her brief life she married and lost three husbands (two divorces, one suicide) and chalked up 22 feature film credits (plus another 21 short / bit-part non-credits, including Chaplin's City Lights). The American Film Institute (damning with faint praise?) ranked her the 22nd greatest female star in Hollywood history. LIBERTY, BACON GRABBERS and NEW YORK NIGHTS (all 1929) (1) Liberty (2) Bacon Grabbers (3) New York Nights (Harlow left-screen) A lucky few aspiring actresses seem to take the giant step from obscurity to the big time in a single bound - Lauren Bacall may be the best example of that - but for many more the road to recognition and riches is long and grinding. -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface ASBJØRN GRØNSTAD Consider this paradox: in Howard Hawks' Scarface, The Shame of the Nation, violence is virtually all-encompassing, yet it is a film from an era before American movies really got violent. There are no graphic close-ups of bullet wounds or slow-motion dissection of agonized faces and bodies, only a series of abrupt, almost perfunctory liquidations seemingly devoid of the heat and passion that characterize the deaths of the spastic Lyle Gotch in The Wild Bunch or the anguished Mr. Orange, slowly bleeding to death, in Reservoir Dogs. Nonetheless, as Bernie Cook correctly points out, Scarface is the most violent of all the gangster films of the eatly 1930s cycle (1999: 545).' Hawks's camera desists from examining the anatomy of the punctured flesh and the extended convulsions of corporeality in transition. The film's approach, conforming to the period style of ptc-Bonnie and Clyde depictions of violence, is understated, euphemistic, in its attention to the particulars of what Mark Ledbetter sees as "narrative scarring" (1996: x). It would not be illegitimate to describe the form of violence in Scarface as discreet, were it not for the fact that appraisals of the aesthetics of violence are primarily a question of kinds, and not degrees. In Hawks's film, as we shall see, violence orchestrates the deep structure of the narrative logic, yielding an hysterical form of plotting that hovers between the impulse toward self- effacement and the desire to advance an ethics of emasculation. Scarface is a film in which violence completely takes over the narrative, becoming both its vehicle and its determination. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Under Contract with the United States Department of Energy

,... Operated by Universities Research Association Inc. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory Under Contract with the United States Department of Energy Vol. 3, No. 33 August 14, 1980 COMPUTING DEPARTMENT REORGANIZES The Computing Department has been reorganized to better serve the scientific community and to take advantage of new technologies. One of the major changes is that PREP-- acronym for Physics Research Equipment Pool-- and Instrument Repair have been transferred from Research Services to the Computing De- partment. Familiar people with new re- sponsibilities include Jeff Appel, who is now associate head of the Computing Depart- ment and head of the new Data Acquisition Group in the Department. The Data Acquis- ition Group includes both the hardware and software efforts associated with gathering data for the high energy physics experi- ments at the Laboratory. (L-R) Jeff Appel, Al Brenner and Art Neubauer. Brenner said, "The meeting Appel, a physicist, joined the was held in an area containing a most Department from the Energy Saver Division. stable and valued computing element," Art Neubauer, who was in charge of referring, of course, to the abacus FREP and Instrument Repair with Research overhead. "It's maintenance free and Services, is now head of the Hardware Group works," he added. which includes PREP, Instrument Repair and Mini-Computer Maintenance, headed by Chuck Andrle and Rich Knowles, respectively. Andrle was with Research Services, and Knowles was already with the Computing Department. "In their new positions, Appel, Neubauer, Andrle and Knowles have increased responsibilities and challenges," said Al Brenner, head of the Computing Department. "We are pleased to have them in these key reorganization positions." For the time being, however, PREP and Instrument Repair will remain physically on the 14th floor of the Central Laboratory. -

Mexico Matters: Change in Mexico and Its Impact Upon the United States

Mexico Matters: Change in Mexico and Its Impact Upon the United States Mexico Matters: Change in Mexico and Its Impact Upon the United States Luis RUbIo Mexico Matters: Change in Mexico and Its Impact Upon the United States Luis RUbIo WWW.WILSONCENTER.ORG/MEXICO Available from : Mexico Institute Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/mexico ISBN: 978-1-938027-14-7 THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR ScHOLARS, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that pro- vide financial support to the Center. The Center is the publisher of The Wilson Quarterly and home of Woodrow Wilson Center Press, dialogue radio and television. For more information about the Center’s activities and publications, please visit us on the web at www.wilsoncenter.org. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense.