ENCYCLOPEDIA of RUSSIAN HISTORY EDITOR in CHIEF James R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

27147 October 2003

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Doing Business in 2004: For more information, visit our Understanding Regulation is website at: the first in a series of annual http://rru.worldbank.org/doingbusiness reports investigating the scope and manner of regulations that enhance business activity and those that constrain it. New quantitative indicators on business regulations and their enforcement can be compared across more than 130 countries, and over time. The indicators Public Disclosure Authorized are used to analyze economic outcomes and identify what reforms have worked, where, and why. Public Disclosure Authorized ISBN 0-8213-5341-1 Doingbusiness in 2004 Doingbusiness iii in 2004 Understanding Regulation A copublication of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation, and Oxford University Press © 2004 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, D.C. 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 05 04 03 A copublication of the World Bank and Oxford University Press. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank cannot guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply on the part of the World Bank any judgment of the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. -

Soviet Wartime Management: the Role of Civil Defense in Leadership Continuity

,...- "'<;.' Ull C.:~Ul" U I .: ..2l. '\:: Central S GkJ ~ Intelligence ~~ Soviet Wartime Management: The Role of Civil Defense in Leadership Continuity Interagency Intelligence Memorandum Volume II-Analysis CIA HISTORiCAL REViEW PROGRAM RELEASE AS SANITIZED Tett Seeret Nll!M 8J-10005JX TCS J6tJI~J December 1983 rn"'' ~,... .._ Top Seuei Nl liM 83-10005JX SOVIET WARTIME MANAGEMENT: THE ROLE OF CIVIL DEF~NSE IN LEADERSHIP CONTINUITY VOLUME II-ANALYSIS Information available as of 25 October 1983 was used in the preparation of this Memorandum. TG& &GQl 8& TeF3 6cu et Tep Sec•o4 CONTENTS Page PURPOSE AND SCOPE....................................................................................... ix KEY JUDGMENTS ............................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER I. SOVIET STRATEGY FOR WARTIME MANAGEMENT...... I-1 A. Soviet Perceptions of Nuclear War ........................................................ I-1 B. Organizational Concepts.......................................................................... I-I CHAPTER II. WARTIME MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE........................... Il-l A. Influence of World War II ............................... :...................................... Il-l B. Peacetime Organizations and F~nctions ................................................ Il-l C. Organizations for the Transition to Wartime........................................ II-7 USSR Defense Council ........................................................................ II-7 Second Departments -

British Family Names

cs 25o/ £22, Cornrll IBniwwitg |fta*g BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcnrti W~ Sage 1891 A.+.xas.Q7- B^llll^_ DATE DUE ,•-? AUG 1 5 1944 !Hak 1 3 1^46 Dec? '47T Jan 5' 48 ft e Univeral, CS2501 .B23 " v Llb«"y Brit mii!Sm?nS,£& ori8'" and m 3 1924 olin 029 805 771 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029805771 BRITISH FAMILY NAMES. : BRITISH FAMILY NAMES ftbetr ©riain ano fIDeaning, Lists of Scandinavian, Frisian, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman Names. HENRY BARBER, M.D. (Clerk), "*• AUTHOR OF : ' FURNESS AND CARTMEL NOTES,' THE CISTERCIAN ABBEY OF MAULBRONN,' ( SOME QUEER NAMES,' ' THE SHRINE OF ST. BONIFACE AT FULDA,' 'POPULAR AMUSEMENTS IN GERMANY,' ETC. ' "What's in a name ? —Romeo and yuliet. ' I believe now, there is some secret power and virtue in a name.' Burton's Anatomy ofMelancholy. LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1894. 4136 CONTENTS. Preface - vii Books Consulted - ix Introduction i British Surnames - 3 nicknames 7 clan or tribal names 8 place-names - ii official names 12 trade names 12 christian names 1 foreign names 1 foundling names 1 Lists of Ancient Patronymics : old norse personal names 1 frisian personal and family names 3 names of persons entered in domesday book as HOLDING LANDS temp. KING ED. CONFR. 37 names of tenants in chief in domesday book 5 names of under-tenants of lands at the time of the domesday survey 56 Norman Names 66 Alphabetical List of British Surnames 78 Appendix 233 PREFACE. -

Pietro Aaron on Musica Plana: a Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri Tres De Institutione Harmonica (1516)

Pietro Aaron on musica plana: A Translation and Commentary on Book I of the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (1516) Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Joseph Bester, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Charles Atkinson Burdette Green Copyright by Matthew Joseph Bester 2013 Abstract Historians of music theory long have recognized the importance of the sixteenth- century Florentine theorist Pietro Aaron for his influential vernacular treatises on practical matters concerning polyphony, most notably his Toscanello in musica (Venice, 1523) and his Trattato della natura et cognitione de tutti gli tuoni di canto figurato (Venice, 1525). Less often discussed is Aaron’s treatment of plainsong, the most complete statement of which occurs in the opening book of his first published treatise, the Libri tres de institutione harmonica (Bologna, 1516). The present dissertation aims to assess and contextualize Aaron’s perspective on the subject with a translation and commentary on the first book of the De institutione harmonica. The extensive commentary endeavors to situate Aaron’s treatment of plainsong more concretely within the history of music theory, with particular focus on some of the most prominent treatises that were circulating in the decades prior to the publication of the De institutione harmonica. This includes works by such well-known theorists as Marchetto da Padova, Johannes Tinctoris, and Franchinus Gaffurius, but equally significant are certain lesser-known practical works on the topic of plainsong from around the turn of the century, some of which are in the vernacular Italian, including Bonaventura da Brescia’s Breviloquium musicale (1497), the anonymous Compendium musices (1499), and the anonymous Quaestiones et solutiones (c.1500). -

International Research and Exchanges Board Records

International Research and Exchanges Board Records A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Karen Linn Femia, Michael McElderry, and Karen Stuart with the assistance of Jeffery Bryson, Brian McGuire, Jewel McPherson, and Chanté Wilson-Flowers Manuscript Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page ii Collection Summary Title: International Research and Exchanges Board Records Span Dates: 1947-1991 (bulk 1956-1983) ID No: MSS80702 Creator: International Research and Exchanges Board Creator: Inter-University Committee on Travel Grants Extent: 331,000 items; 331 cartons; 397.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English and Russian Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: American service organization sponsoring scholarly exchange programs with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the Cold War era. Correspondence, case files, subject files, reports, financial records, printed matter, and other records documenting participants’ personal experiences and research projects as well as the administrative operations, selection process, and collaborative projects of one of America’s principal academic exchange programs. International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page iii Contents Collection Summary .......................................................... ii Administrative Information ......................................................1 Organizational History..........................................................2 -

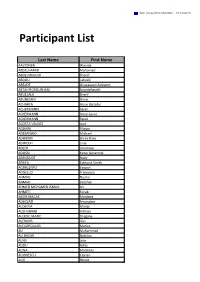

Participant List

Ref. Ares(2015)5922007 - 17/12/2015 Participant List Last Name First Name AALTONEN Wanida ABDELHAMID Mohamed ABDELMEGUID Sheref ABDOU Lahadji ABEJIDE Oluwaseun Adeyemi ABTAHIFOROUSHANI Seyedehasieh ABUELALA Sherif ABUNEMEH Omar ACHARYA Arjun Bahadur ACHERMANN Sarah ACKERMANN Anne-Laure ACKERMANN Raoul ACOSTA VALDEZ Jose ADDARII Filippo ADESANWO Michael ADHIKARI Shree Ram ADINOLFI Livia ADLER Jéromine ADOSSI Yawo Nevemde AERNOUDT Rudy AFRIFA Edmund Smith AGBALENYO Yawovi AGNELLO Francesca AHMAD Najma AHMAD Zeeshan AHMED MOHAMED ISMAIL Ali AHMETI Korab AKSIN MACAK Marijana ALBIZZATI Amandine ALCHEVA Marija ALDHUBAIBI Hitham ALEKSIC MATIC Dragana ALEXAKIS Ilias ALEXOPOULOS Marios ALI Muhammad ALI BACAR Nabilou ALIAS Jose ALIDU Adilu ALINA Marinoiu ALIONESCU Ciprian ALIX Nicole ALLET Marion ALMAZYAN Lida ALMEIDA Katia ALONSO Beatriz ALSAWALAH Abedallah ALTINOK Salih ALVARADO TANAMACHI Sayuri ALVAREZ Ana ALVES Filipe AMADIO Nicolas AMALFITANO Marie AMAZIT Anaïs AMBROSIO Giuseppe AMET Suzon AMITSIS Gabriel ANASTOPOULOS Konstantinos ANCA Gunta ANCEL Florian ANDRES Rodolphe ANDREU Tomás ANDREW Mwebaza ANDRICOPOULOU Anna ANDRIOT Patricia ANDRITSOU Anastasia ANESE Tobia ANGELOVA Milena ANNE Leautier ANSELM Cecile APOLLONI Guglielmo APOSTOLIDIS Catherine APPEL Ulrik ARNOLD David AROYAN Luciné ARREGUI Karin Arriaga Sierra Hermes ARROYO DE SANDE Carmen ARVANITI Chrysafo ASCHARI-LINCOLN Jessica ASLAN Ayse ASRAF Adeeba ASSABA Inès ATAMAN SCHARNING Ayşegül ATAYI Ayoko Veronique ATHANASIADOU Natasha Marie AUCONIE Sophie AUGER Christophe AVENTAGGIATO Giovanni -

Doing Business in 2005 -- Removing Obstacles to Growth

Doing Business A copublication of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation and Oxford University Press in 2005 Removin g O b s ta c l e s t o Growth © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, D.C. 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www.worldbank.org E-mail [email protected] All rights reserved. 1 2 3 4 08 07 06 05 A copublication of the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation and Oxford University Press. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the gov- ernments they represent. The World Bank cannot guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The bound- aries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply on the part of the World Bank any judgment of the legal status of any territory or the en- dorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is copyrighted. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permis- sion of the World Bank. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint, please send a request with complete information to: Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com. -

Retrospect Index of Authors by Surname 1974 - 2017

Retrospect Index of Authors by Surname 1974 - 2017 Doug Aarstad 1983 Print and Publishing Amy Barker 1979 Poetry Doug Aarstad 1984 Graphic Printers Amy Barker 1980 Poetry, Short Story Ellen Acker 1983 Artwork Victoria Barrett 1984 Graphic Printers Ronda Ackerman 1988 Poetry Danita Barton 1976 Artwork D'Anne Adams 1995 Poetry Sarah Baylinson 2003 Artwork, Photography, Staff D'Anne Adams 1996 Themes Darren BcKean 1989 Artwork Kristen Adamson 2001 Poetry Sandy Beardsley 1976 Poetry Annie Agars 1988 Artwork Brendan Beardsley 2001 Short Stories Annie Agars 1989 Artwork Lucy Beck 2017 Artwork Jim Aikins 1991 Artwork Arlana Beckenhauer 1981 Artwork Logan Aimone 1990 Artwork Kandice Beedle 2000 Poetry Logan Aimone 1991 Editor, Artwork, Short Story Kortni Beedle 2001 Photography Logan Aimone 1992 Short Stories Val Beimborn 1993 Poetry Jim Akins 1990 Artwork Kelle Belbeck 1980 Staff, Short Story Ellen Akker 1985 Photography, Artwork Becki Bell 1993 Short Story Gordon Albertson 1978 Photography Jimmy Bell 1995 Poetry Shannon Alderson 1988 Artwork Tom Bellah 2016 Short STory Shannon Alderson 1989 Artwork David Bellande 1977 Poetry Tom Alexander 1981 Short Story Cathy Bellande 1981 Poetry Mindy Alldredge 2007 Poetry Valentyna Belofsky 2017 Poetry Rosella Allemand 1990 Artwork Sara Bergman 1999 Poetry Diane Allen 1984 Poetry William Berkinbine 1985 Graphic Delayna Allen 1990 Photography Franziska Beuscher 2003 Artwork, Essay Dave Allen 1996 Photography Leone Bicchieri 1981 Short Story, Poetry Toby Allenbaugh 1976 Artwork Pedro Bicchieri 1981 Poetry, -

Surname Files

Andrews Bailey A Angel Bain Anglin Baird Abbott Applegate Baker Abel Arana Bal Abercrombie Arant Baldwin Abernathy Archer Bales Abrams Arends Ball Abramson Armes/Arms Ballantyne Adam Armour Ballard Adams Armstrong Baller Addison Arndt Balzer Adkins Arney Bancroft Adolf Arnold Baney Adrian Arrance Banks Aebi Arthur Banner Agalzoff Ashby Bansen Agard Asher Banta Agee Ashford Barba Agena Ashley Barber Aguirre Ashton Barclay Ainsworth Ashwill Barcroft Akers Aspinwall Barendrecht Albert Atherton Barker Albiker Athey Barlow Albrecht Atkins Barnard Alderman Atwater Barnes Alderson Auer Barnett Aldrich August Barney Aldridge Ault Barnhart Alexander Austin Barnum Alleman Autritt Barrett Allen Avera Barrows Allgood Avila Barry Allingham Ayer Bartchy Allison Aynes Bartel Allister Bartell Allphin Barth Allred B Bartholomew Alsip Barton Alvarez Baal Bartruff Amaya Babb Barwig Ames Babcock Basey Amos Bagley Baskett Andersen Bahler Bass Anderson Bahr Bassett Andrew Baich Bates Bethell Bolejack Bathke/Bathkey Bettencourt Bollman Bauer Betts Bolter Baughman Bevens Bolton Baxter Beveridge Boman Bayer Bewley Bond Beach Beyerle Bones Beagle Bibler Bookey Beall Bice Boone Bean Biddle Booth Beard Bier Boothby Beardsley Bigelow Boozer Beaton Bills Boquist Beaty Bilyeu Bork Beauchamp Birch Bose Beaver Bird Bossatti Beck Birks Bostwick Becker Bisbee Bosvert Beckett Bishop Bounds Beders Bissell Boustead Bedwell Black Bovard Beebe Blackley Bowden Bell Blackwell Bowe Belshaw Blaine Bowerman Belt Blair Bowers Bemrose Blake Bowler Benedict Blakely Bowles Benefiel -

Becoming Soviet: Lost Cultural Alternatives In

BECOMING SOVIET: LOST CULTURAL ALTERNATIVES IN UKRAINE, 1917-1933 Olena Palko, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History December 2016© ‘This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition any quotation or extract must include full attribution.’ Abstract This doctoral thesis investigates the complex and multi-faceted process of the cultural sovietisation of Ukraine. The study argues that different political and cultural projects of a Soviet Ukraine were put to the test during the 1920s. These projects were developed and executed by representatives of two ideological factions within the Communist Party of Bolsheviks of Ukraine: one originating in the pre-war Ukrainian socialist and communist movements, and another with a clear centripetal orientation towards Moscow. The representatives of these two ideological horizons endorsed different approaches to defining Soviet culture. The unified Soviet canon in Ukraine was an amalgamation of at least two different Soviet cultural projects: Soviet Ukrainian culture and Soviet culture in the Ukrainian language. These two visions of Soviet culture are examined through a biographical study of two literary protagonists: the Ukrainian poet Pavlo Tychyna (1891-1967) and the writer Mykola Khvyl'ovyi (1893-1933). Overall, three equally important components, contributing to Ukraine’s sovietisation, are discussed: the power struggle among the Ukrainian communist elites; the manipulation of the tastes and expectations of the audience; and the ideological and aesthetic evolution of Ukraine’s writers in view of the first two components. -

Crimean Tatars from Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 6 5-30-2015 Crimean Tatars From Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea Karina Korostelina George Mason University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Korostelina, Karina (2015) "Crimean Tatars From Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 1: 33-47. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.9.1.1319 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Crimean Tatars From Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea Karina Korostelina George Mason University Arlington, VA, USA Abstract: The article begins with a description of the deportation of Crimean Tatars. It provides a brief review of the German Occupation of Crimea, examines the negative images of Crimean Tatars published in Soviet newspapers between 1941-1943 and the explicit rationale given by the Soviet authorities for the deportation of Crimean Tatars, and reviews the mitigation of hostilities against Tatars in the years following the war. The article continues with accounts of the attempts to repatriate Crimean Tatars after 1989 and the discriminative policies against the returning people. The conclusion of the article describes current hardships experienced by Tatars in occupied Crimea. -

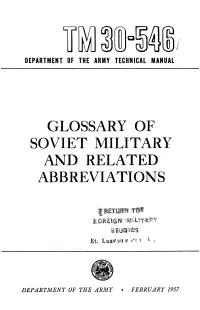

Glossary of Soviet Military and Related Abbreviations

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY TECHNICAL MANUAL GLOSSARY OF SOVIET MILITARY AND RELATED ABBREVIATIONS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FFEBRUARY 1957 TM 30-546 TECHNICAL MANUAL DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 30-546 WASHINGTON 25, D. C., 31 December 1956 GLOSSARY OF SOVIET MILITARY AND RELATED ABBREVIATIONS Page Transliteration table for the Russian language ......................-.. ii Abbreviations for use with this manual .......-.........................- ...... iii Grammatical abbreviations ...----------------------.....- ---- iv Foreword --------------------- -- ------------------------------------------------------- 1 Glossary of Soviet military and related abbreviations-.................-......... 3 TRANSLITERATION TABLE FOR THE RUSSIAN LANGUAGE The Russian alphabet has 33 letters, which are here listed together w [th their transliteration as adopted by the Board on Geographic Names. A a AG a P pd C °c C B B 3 e T T cAl/ r rJCT y A D d B cSe ye,et X xZ "s ts ch )K3J G "0 sh 314 C ' shch b b hi bi 'b *i, H H KG 10 10j Oo (90 51 31 1L / p ye initially, after vowel. andl after 'b, b; e e1~ewhere. When written as a in Rusoian, transliterate a5~ yii or e. Use of diacritical marks is. preferred, but such marks may be omitted when expediency (apostrophe), palatalize. a preceding consonant, giving a sound resembling the consonant plus y!, somewhat as in English meet you, did you. 3The symbol " (double apostrophel, not a repetition of the line above. No sound; used only after certain prefixe.- before the vowvel letter: c. e. 91. 10. ii ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS