Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pokemon Buy List

Pokemon Buy List Card Name Set Rarity Cash Value Credit Value Absol EX - XY62 XY Promos Holofoil $1.04 $1.24 Acerola (Full Art) SM - Burning Shadows Holofoil $6.16 $7.39 Acro Bike (Secret) SM - Celestial Storm Holofoil $5.11 $6.13 Adventure Bag (Secret) SM - Lost Thunder Holofoil $2.72 $3.26 Aegislash EX XY - Phantom Forces Holofoil $1.06 $1.27 Aegislash V SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $0.68 $0.82 Aegislash V (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $3.96 $4.75 Aegislash VMAX SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $1.07 $1.28 Aegislash VMAX (Secret) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $6.28 $7.54 Aerodactyl EX - XY97 XY Promos Holofoil $0.84 $1.00 Aerodactyl GX SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $0.88 $1.05 Aerodactyl GX (Full Art) SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $1.56 $1.87 Aerodactyl GX (Secret) SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $5.40 $6.48 Aether Foundation Employee Hidden Fates: Shiny Vault Holofoil $3.32 $3.98 Aggron EX XY - Primal Clash Holofoil $0.97 $1.16 Aggron EX (153 Full Art) XY - Primal Clash Holofoil $4.27 $5.12 Air Balloon (Secret) SWSH01: Sword & Shield Base Set Holofoil $4.57 $5.48 Alakazam EX XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $1.28 $1.53 Alakazam EX (Full Art) XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $3.37 $4.04 Alakazam EX (Secret) XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $5.32 $6.38 Alakazam V (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $3.92 $4.70 Allister (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $5.70 $6.84 Allister (Secret) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $7.99 $9.58 Alolan Exeggutor GX SM - Crimson Invasion Holofoil $0.80 $0.96 Alolan Exeggutor GX (Full Art) SM - Crimson Invasion -

Gender-Sternchen, Binnen-I Oder Generisches Maskulinum, … (Akademische) Textstile Der Personenreferenz Als Registrierungen?*

Gender-Sternchen, Binnen-I oder generisches Maskulinum, … (Akademische) Textstile der Personenreferenz als Registrierungen?* Helga Kotthoff (Freiburg) Abstract For more than 40 years, a debate on gender-related person references has been taking place in the German-speaking world. My contribution starts with a differentiation of four registers, which are currently practiced in writing and have developed specific reasoning discourses and specific social contexts of usage, as I try to show. I am going to examine these four styles of gendered person reference as “registers” in the sense of anthropological linguistics (Agha 2007). This concept of “enregisterment” implies that the producers connect themselves to a socio-symbolic cosmos and can be perceived with cultural evaluations (in production and re- ception), for example, as conservative, feminist, queer, liberal (Kotthoff 2017). Here I shall explore their (socio)linguistic underpinnings within conceptions of language ideology in order to grasp the communication-reflexive charges of these discourses. 1 Einleitung Seit über 40 Jahren findet im deutschsprachigen Raum eine Debatte um geschlechterbezogene Personenreferenzen statt. Mein Beitrag setzt bei einer Binnendifferenzierung von vier Registern an, die sich inzwischen mit spezifischen sozialen Verortungen herausgebildet haben, was ich zu zeigen versuche. Die traditionelle Schreibpraxis mit einem generisch gemeinten, ge- schlechtsübergreifenden Maskulinum1 (Typ 1), wie sie etwa von Eisenberg (2017), Glück (2018) oder dem Verein für Deutsche -

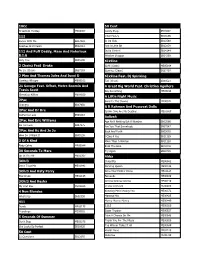

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

Graphemic Methods for Genderneutral

Graphemic Methods for GenderNeutral Writing Yannis Haralambous & Joseph Dichy Abstract. In this paper we present a model and a classification of graphemic genderneutral writing methods, we explore current practices in French, Ger man, Greek, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish languages, and we investigate in teractions between genderneutral writing forms and regular expressions. 1. Introduction: The General Issue of, and behind, Gender Neutral Writing The issue behind genderneutral writing is that of the representation of intergender relations carried by languages. What is at stake is the representation of equality, or not, between genders. The issue is also re ferred to as “inclusive writing,” which apparently refers to human rights, but does not cover all cases, i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. The term “GenderNeutral Writing” is, in fact, both clearer and more inclusive. Generally speaking, languages are conservative, if not archaic. A sig nificant example is that of the idea of time, which is traditionally repre sented as a dot sliding along a straight line in a continuous movement. This has been a philosophical image of time since ancient Greek philoso phers and throughout the Middle Ages both in Arabic and European phi losophy, but can no longer be considered as a valid representation after 20th century existentialist philosophers and Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. Yannis Haralambous 0000-0003-1443-6115 IMT Atlantique & LabSTICC UMR CNRS 6285 Brest, France [email protected] Joseph Dichy Professor of Arabic linguistics Lyon, France [email protected] Y. Haralambous (Ed.), Graphemics in the 21st Century. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

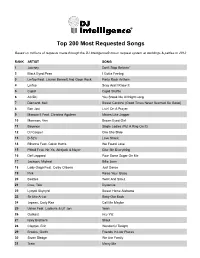

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 7 3-15-2011 Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything Alan Wilcox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan Wilcox, Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything, 31 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 1 (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol31/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything By Alan Wilcox* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. ....... 254 II. PAST AND CURRENT RESTRICTIONS ON VIOLENCE IN VIDEO GAMES ........................................... 256 A. The Origins of Video Game Regulation...............256 B. The ESRB ............................. ..... 263 III. RESTRICTIONS IMPOSED IN OTHER COUNTRIES . ............ 275 A. The European Union ............................... 276 1. PEGI.. ................................... 276 2. The United -

The “Jūdō Sukebei”

ISSN 2029-8587 PROBLEMS OF PSYCHOLOGY IN THE 21st CENTURY Vol. 9, No. 2, 2015 85 THE “JŪDŌ SUKEBEI” PHENOMENON: WHEN CROSSING THE LINE MERITS MORE THAN SHIDŌ [MINOR INFRINGEMENT] ― SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND INAPPROPRIATE BEHAVIOR IN JŪDŌ COACHES AND INSTRUCTORS Carl De Crée University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium International Association of Judo Researchers, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The sport of jūdō was intended as an activity “for all”. Since in 1996 a major sex abuse scandal broke out that involved a Dutch top jūdō coach and several female elite athletes, international media have identified many more abuses. To date no scholarly studies exist that have examined the nature, extent, and consequences of these anomalies. We intend in this paper to review and analyze sexual abuses in jūdō. To do so we offer a descriptive jurisprudence overview of relevant court and disciplinary cases, followed by a qualitative-analytical approach looking at the potential factors that prompt jūdō-related bullying and sexual harassment. Sex offenders may be attracted to jūdō because of: 1. the extensive bodily contact during grappling, 2. the easy access to voyeuristic opportunities during contest weigh-ins and showering, 3. Jūdō’s authoritarian and hierarchical structure as basis for ‘grooming’, 4. lack of integration of jūdō’s core moral component in contemporary jūdō coach and instructor education, and 5. its increasing eroti- cization by elite jūdō athletes posing for nude calendars and media and by specialized pornographic jūdō manga and movies. Cultural conceptions and jurisprudence are factors that affect how people perceive the seriousness and how these offences are dealt with. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

ABSTRACT LOHMEYER, EDWIN LLOYD. Unstable Aesthetics

ABSTRACT LOHMEYER, EDWIN LLOYD. Unstable Aesthetics: The Game Engine and Art Modifications (Under the direction of Dr. Andrew Johnston). This dissertation examines episodes in the history of video game modding between 1995 and 2010, situated around the introduction of the game engine as a software framework for developing three-dimensional gamespaces. These modifications made to existing software and hardware were an aesthetic practice used by programmers and artists to explore the relationship between abstraction, the materiality of game systems, and our phenomenal engagement with digital media. The contemporary artists that I highlight—JODI, Cory Arcangel, Orhan Kipcak, Julian Oliver, and Tom Betts—gravitated toward modding because it allowed them to unveil the technical processes of the engine underneath layers of the game’s familiar interface, in turn, recalibrating conventional play into sensual experiences of difference, uncertainty, and the new. From an engagement with abstract forms, they employed modding techniques to articulate new modes of aesthetic participation through an affective encounter with altered game systems. Furthermore, they used abstraction, the very strangeness of the mod’s formal elements, to reveal our habitual interactions with video games by destabilizing conventional gamespaces through sensory modalities of apperception and proprioception. In considering the imbrication of technics and aesthetics in game engines, this work aims to resituate modding practices within a dynamic and more inclusive understanding -

The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists See Story Page 8

fall 2010 The Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists Leading the See story digital (r)evolution page 8 68253-1_P2028-ACTRA-fall10.indd 1 9/7/10 1:41 PM inSide your union magazine... interACTRA PRESIDENT’S MESSaGE 3 by Ferne Downey Fall 2010, Volume 17, Issue 2 InterACTRA is the official pub- ONlINE ThEfT TakES MONEy 4 lication of ACTRA (Alliance of OuT Of all OuR POckETS Canadian Cinema, Television page 8 and Radio Artists), a Canadian canada’s new copyright bill needs to be fixed union of performers affiliated to by Yannick Bisson the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and the International page 10 Federation of Actors (FIA). ThE INTERNET chaNNEl 8 InterACTRA is free of charge to all ACTRA members. leading the digital (r)evolution EdIToRIAL AdVIsoRy by Eli Goree CommITTEE: Joanne deer, Ferne downey, Brian Gromoff, Richard Hardacre, Carol Taverner, TV’s DIGITal EVOluTION 12 Theresa Tova, stephen Waddell. Republic of Doyle embraces their fans online ConTRIBuToRs: Tina Alford, by Ruth Lawrence dJ Anderson, yannick Bisson, mike Burns, marlene Cahill, nicholas Campbell, Joanne MEDIa EVOluTION 14 deer, Ferne downey, Anna Falsetta, Chris Faulkner, megan by Stephen Waddell If you’re adaptable you stay Gariepy, Raymond Guardia, page 14 Eli Goree, Allan Hawco, Alex Ivanovici, Brad Keenan, Geoff TElEPhONy facTS wITh 16 one step ahead of the game Lapaire, Ruth Lawrence, Rob BEll caNaDa’S EMIly macklin, Tyrel mcnicol, dan o’Brien, Adam Reid, Gisèle by Gisèle Rousseau Rousseau, Gary saxe, Alison stewart, marit stiles, Amanda Tapping, Theresa Tova, stephen DIGITal PERfORMaNcE IN aN awaRD- 18 Waddell, Christine Webber, wINNING RENaISSaNcE VIDEOGaME Christine Willes. -

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT ("Agreement")

-·- ·· -·--- ---------- INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT ("Agreement") covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the "Guild") and The CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION ("CFTPA") and THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TELJ~:VISION DUQUEBEC ("APFTQ") (the "Associations") January 1, 2010 to December 31, 20 II © 2010 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION AND THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TELEVISION DU QUEBEC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General -AU Productions p. Article AI Recognition, Application and Term p. Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 16 Article AS Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p.22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p.24 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p.29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article AIO Security for Payment p.42 Article All Payments p.44 Article Al2 Administration Fee p.52 Article Al3 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer's Fees p. 52 Article Al4 Contributions and Deductions from Writer's Fees in the case of Waivers p.54 Section 8: Conditions Governing Engagement p.55 Article 81 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p.55 Article 82 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 61 Article 83 Options p.62 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p.63 Article Cl Feature Film p.63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p.