Front Line Defenders (If Applicable)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JE in CBI Net for Sexual Abuse of Children Were Travelling in When It Get Any Time to Come out Down from Road Caught Fire After a Collision and Were Burnt Alive

WWW.YUGMARG.COM FOLLOW US ON REGD NO. CHD/0061/2006-08 | RNI NO. 61323/95 Join us at telegram https://t.me/yugmarg Wednesday, November 18, 2020 CHANDIGARH, VOL. XXV, NO. 276, PAGES 12, RS. 2 YOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER Govt to develop Sugarcane research More snow in HP, CSK should not colonies for poor in institute to be Keylong retain Dhoni if urban areas: game changer for freezes at minus there's a mega Dushyant; Middle farmers: Randhawa; 6.6 degrees auction, says class also be Says, institute to Chopra benefitted boost per acre yield PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 12 Delhi heads for Countries supporting terrorists another lockdown should to be held guilty: Modi in busy markets AGENCY Guv convenes NEW DELHI, NOV 17 winter Session of As cases of coronavirus are rising in HP legislative BRICS Summit: Launches veiled attack on Pakistan the national capital, the Delhi Gov- ernment has sent a proposal to the Assembly AGENCY Centre, that if needed, markets SHIMLA : Himachal Pradesh NEW DELHI, NOV 17 COVID-19 has given flouting safety protocols and emerg- Governor Bandaru Datatrya ing as COVID-19 hotspots, be on Tuesday convened the Terrorism is the biggest problem us opportunity to closed for a few days, Chief Minis- winter session of State leg- the world is facing at present, said develop new ter Arvind Kejriwal said on Tues- islative assembly , which Prime Minister Narendra Modi day. would start from December 7 on Tuesday at the BRICS Summit protocols, says PM "Since cases are rising in Delhi, at Tapovan near Dharmshala. -

PTM, Irredentist Afghan Claims on Pakhtunkwa & Pakistan Army

PTM, irredentist Afghan claims on Pakhtunkwa & Pakistan army Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, PTM, is a peaceful movement for people’s rights violated in the war on terror that especially devastated certain Pashtun areas in the northwest of Pakistan. Political parties of Pakistan could not change the military controlled Afghan policy that was causing the devastation and Pakistan army allowed all the devastation as ‘collateral damage’. The result: within about one and a half decade the PTM emerged in the area, driven by the ‘children of war’— former child victims of the war. The movement is led by 24 years old Manzoor Pashteen, who also grew up a war child. Civilian governments in Pakistan have little control over Afghan policy of Pakistan and expecting anything from them is useless. The PTM, therefore, directly addressed its demands to the concerned authorities: the power generals of Pakistan. The demands include: end to extrajudicial killings; end to forced disappearance plus presentation of the disappeared persons to the court of law ; dignified treatment of public at military check posts in the war on terror affected areas; removal of landmines in Waziristan and justice for Naqeebullah Mahsud, an emerging fashion model, extra judicially killed by, Anwar Rao, the police officer known to have extra judicially killed 100s of innocent Pakistanis in Kararchi. The initial reaction of the generals was careful, to an extent positive and a bit of a ‘guarded sympathy’. Major-General Asif Ghafoor, former director-general of Inter-Services Public Relations (DGISPR), who met Manzoor Pashteen, called him ’a wonderful young boy’. He even said that the army chief had given strict instructions not to deal with PTM gatherings with force. -

Asia Times Online :: South Asia News, Business and Economy from India

Asia Times Online :: South Asia news, business and economy from India ... http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/MA15Df01.html Front Page South Asia Greater China China Business Jan 15, 2011 South Asia Southeast Asia Share | More Japan Korea Al-Qaeda to unleash Western jihadis Middle East By Syed Saleem Shahzad and Tahir Ali Central Asia World Economy ISLAMABAD - With the Afghan war entering its 10th year, Asian Economy IT World completely undeterred by the American drone strikes in the Pakistani tribal region, al-Qaeda is putting the final touches to Book Reviews Letters plans to recruit, train and launch Western Caucasians in their Forum countries; the aim is to spread the flames of the South Asian war theater to the West. Al-Qaeda began planning the operation in 2002, after the fall in late 2001 of the Taliban in Afghanistan, where the group had been given sanctuary. Al-Qaeda had regrouped in Pakistan's South Waziristan tribal area on the border with Afghanistan, and used this base to developed propaganda media structures to recruit in Freedom fighters for a fading empire (Jan 11, '11) 1. China tries to steal a march 2. Weapons giant becomes Big Brother 3. Sodomy and Sufism in Afgaynistan 4. Masters of hate locked and loaded the West. (See The legacy of Nek Mohammed Asia Times Online, July 20, 2004.) 5. Nation of 'wusses' gets Now, after eight years, a picture is emerging that shows the wake-up call failure of Western intelligence to asses the real pulse of their 6. North Korea's societies, and the inability of North Atlantic Treaty Organization end is nigh - or is forces to prevent Afghanistan from once again becoming the it? nerve center of al-Qaeda's terror operations. -

Pakistan's State-Terrorism and the Plight of the Pashtun

COMMENT COMMENT 197 – On the Asian Century, Pax Sinica & Beyond (XIII): Pakistan’s state-terrorism and the plight of the Pashtuns By Siegfried O. Wolf 30 September 2020– DOI: 10.48251/SADF.ISSN.2406-5617.C197 Dr. Siegfried O. Wolf, Director of Research at SADF (Coordinator: Democracy Research Programme); he was educated at the Institute of Political Science (IPW) and South Asia Institute (SAI), both Heidelberg University. Additionally he is member (affiliated researcher) of the SAI as well as a former research fellow at IPW and Centre de Sciences Humaines (New Delhi, India). In North-West Pakistan, that is in the global epicentre of Jihadism, Islamic extremism, and militancy, a new peaceful, socio-political movement has emerged. Facing a double threat, from regional and international terrorists on one side and from the federal government and its security sector agents on the other, local Pashtuns articulated their grievances and launched the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (Movement for the protection of Pashtuns, PTM). Led by liberal and secular politicians and activists, the civic grassroots initiative PTM gained much popularity in the region during the last few years and is translating the human incurred suffering by the Pashtuns into a national discourse with growing international significance. Today, the PTM is one of the ‘most powerful human rights voices’ in Pakistan. Being the target of numerous, heavily armed campaigns by both the Pakistani army (for example Operations Zarb-e-Azb and Rah-e-Nijat) and by militant groups, areas of Pashtun settlements are largely destroyed. Livelihoods have been spoiled, and millions of people were or are still displaced. -

Annual Report

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN ...................................................................................................... 3 SENATE SESSIONS ................................................................................................................................. 5 LEGISLATION AT A GLANCE ................................................................................................................. 7 LEGISLATIVE ACHIEVEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 7 Senator-Wise Private Members’ Bills introduced in the Senate during the Parliamentary Year 2019-2020 ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Senators-wise Private Members’ Bills passed by the Senate during Parliamentary Year 2019- 2020 .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Private Members’ Bills referred for consideration in Joint Sitting of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) ................................................................................................................................... 10 Governmment Bills Passed by the Senate during PY 2019-20 .................................................... 10 LAYING OF CONSTITUTIONAL / STATUTORY REPORTS ........................................................... 11 Constitutional / Statutory Reports laid during -

A Case Study of Mahsud Tribe in South Waziristan Agency

RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY By MUHAMMAD IRFAN MAHSUD Ph.D. Scholar DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (SESSION 2011 – 2012) RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (December, 2018) DDeeddiiccaattiioonn I Dedicated this humble effort to my loving and the most caring Mother ABSTRACT The beginning of the 21st Century witnessed the rise of religious militancy in a more severe form exemplified by the traumatic incident of 9/11. While the phenomenon has troubled a significant part of the world, Pakistan is no exception in this regard. This research explores the role of the Mahsud tribe in the rise of the religious militancy in South Waziristan Agency (SWA). It further investigates the impact of militancy on the socio-cultural and political transformation of the Mahsuds. The study undertakes this research based on theories of religious militancy, borderland dynamics, ungoverned spaces and transformation. The findings suggest that the rise of religious militancy in SWA among the Mahsud tribes can be viewed as transformation of tribal revenge into an ideological conflict, triggered by flawed state policies. These policies included, disregard of local culture and traditions in perpetrating military intervention, banning of different militant groups from SWA and FATA simultaneously, which gave them the raison d‘etre to unite against the state and intensify violence and the issues resulting from poor state governance and control. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Media As an Instrument of Hybrid Warfare: a Case Study of Pakistan

p- ISSN: 2708-2105 p- ISSN: 2709-9458 L-ISSN: 2708-2105 DOI: 10.31703/gmcr.2021(VI-I).02 | Vol. VI, No. I (Winter 2021) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gmcr.2021(VI-I).02 | Pages: 12 – 27 Media as an Instrument of Hybrid Warfare: A Case Study of Pakistan Haseeb ur Rehman Warrich * Muhammad Waqas Haider † Tahir Mahmood Azad ‡ Headings Abstract: This paper aims to analyze the role of media as an • Introduction instrument of Hybrid warfare to shape public opinion and to see its • Media Types and impact on different organs of state. 21st Century dawned alongside an Classification emerging form of warfare called Hybrid Warfare, one which in its nature and character is remarkably diverse and whose scope extends • Media Warfare and beyond conventional elements of war, that is to say, domain, Image-fare adversary, objective, and force. Modern wars, owing to asymmetric • Hybrid Warfare lines of conflict, are difficult to be categorized as conventional or • Impact of Media on counterinsurgency and are in stark contrast to traditional models of National Security war and peace. Given the multifaceted dimensions of this new concept • Dynamics of Social of waging war, it is significant to evaluate its contours and grasp an Media understanding of its nature and instruments. Does the paper evaluate • Conclusion how it can play a pivotal role to mitigate existing and future challenges • References being faced by Pakistan in the domain of Hybrid Warfare? Key Words: Hybrid Warfare, Media, Social Media, Perception, Pakistan. Introduction During World War-I, the Central Powers (Germany, Austria- Hungary, Italy, and Turkey) and Allied Powers (Russia, France, Great Britain, and the United States) used the press as a propaganda tool. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 494 | MAY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan By Amira Jadoon Contents Introduction ...................................3 The Rise and Decline of the TTP, 2007–18 .....................4 Signs of a Resurgent TPP, 2019–Early 2021 ............... 12 Regional Alliances and Rivalries ................................ 15 Conclusion: Keeping the TTP at Bay ............................. 19 A Pakistani soldier surveys what used to be the headquarters of Baitullah Mehsud, the TTP leader who was killed in March 2010. (Photo by Pir Zubair Shah/New York Times) Summary • Established in 2007, the Tehrik-i- attempts to intimidate local pop- regional affiliates of al-Qaeda and Taliban Pakistan (TTP) became ulations, and mergers with prior the Islamic State. one of Pakistan’s deadliest militant splinter groups suggest that the • Thwarting the chances of the TTP’s organizations, notorious for its bru- TTP is attempting to revive itself. revival requires a multidimensional tal attacks against civilians and the • Multiple factors may facilitate this approach that goes beyond kinetic Pakistani state. By 2015, a US drone ambition. These include the Afghan operations and renders the group’s campaign and Pakistani military Taliban’s potential political ascend- message irrelevant. Efforts need to operations had destroyed much of ency in a post–peace agreement prioritize investment in countering the TTP’s organizational coherence Afghanistan, which may enable violent extremism programs, en- and capacity. the TTP to redeploy its resources hancing the rule of law and access • While the TTP’s lethality remains within Pakistan, and the potential to essential public goods, and cre- low, a recent uptick in the number for TTP to deepen its links with ating mechanisms to address legiti- of its attacks, propaganda releases, other militant groups such as the mate grievances peacefully. -

Why Is PTM Becoming a Major Challenge for Pakistan's Ruling

SADF COMMENT Why is PTM becoming a major challenge for 09 May 2019 Issue n° 140 Pakistan’s ruling establishment? ISSN 2406-5617 Farooq Yousaf Farooq Yousaf is an SADF Fellow and a PhD Politics Candidate from Peshawar, Pakistan, currently Pakistan is currently facing a number of challenges both at home and pursuing studies at the University abroad. Domestically the country has locked horns with its arch-rival of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. His India on the Eastern border, while also facing security threats in its research focuses on the role of Western border shared with Afghanistan. However, the issue most indigenous conflict resolution threatening to Pakistan’s “all-powerful” military establishment is the methods in countering Insurgency rise of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), a secular movement in the tribal areas of Pakistan, whereas he using postcolonial of young Pashtun citizens demanding rights for the Pashtun tribal critique as his theoretical areas (formerly known as FATA - Federally Administered Tribal framework. Areas). The PTM was formed on the back of a relatively small - yet powerful - protest in Islamabad against the extra-judicial killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud, a resident of the then FATA region, in January 2018. Mehsud, who had moved to Pakistan’s port city of Karachi so as to earn a livelihood and pursue a career in modelling, was kidnapped by Karachi’s Counter Terrorism Department (CTD) on fake charges of terrorism and was later murdered in a “fake encounter”. To protest this murder, Pashtuns from the former FATA region, who were also joined by the members of the civil society, staged a sit-in protest in Islamabad, in February 2018, demanding not only justice for Mehsud but also for the wider community of “tribal” Pashtuns as Avenue des Arts 19 the whole. -

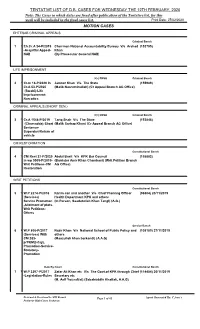

Tentative List of Db Cases for Wednesday

TENTATIVE LIST OF D.B. CASES FOR WEDNESDAY THE 12TH FEBRUARY, 2020 Note: The Cases in which dates are fixed after publication of the Tentative list, for this week will be included in the final cause list. Print Date: 07/02/2020 MOTION CASES EHTESAB CRIMINAL APPEALS Criminal Bench 1 1 Eh.Cr.A 34-P/2019 Chairman National Accountability Bureau V/s Arshad (153795) -Acquittal Appeal- Khan NAB (Dy Prosecuter General NAB) LIFE IMPRISONMENT 9(c) CNSA Criminal Bench 2 1 Cr.m 18-P/2020 In Jamroz Khan V/s The State (155989) Cr.A 53-P/2020 (Malik Nasruminullah) (Cr Appeal Branch AG Office) (Swabi)-Life Imprisonment- Narcotics CRIMINAL APPEALS:(SHORT SEN.) 9(c) CNSA Criminal Bench 3 1 Cr.A 1548-P/2019 Tariq Shah V/s The State (153848) (Charsadda)-Short (Malik Sarfraz Khan) (Cr Appeal Branch AG Office) Sentence- Superdari/Return of vehicle CM RESTORRATION Constitutional Bench 4 1 CM Rest 21-P/2020 Abdul Basit V/s KPK Bar Council (155882) in wp 5509-P/2019- (Barrister Amir Khan Chamkani) (Writ Petition Branch Writ Petitions-CM AG Office) Restoration WRIT PETITIONS Constitutional Bench 5 1 W.P 2274-P/2016 Karim Jan and another V/s Chief Plannng Officer (98804) 20/11/2019 (Services) Health Department KPK and others Service Promotion (In Person, Saadatullah Khan Tangi) (A.G.) ,Allotment of plots- Writ Petitions- Others Service Bench 6 2 W.P 806-P/2017 Nazir Khan V/s National School of Public Policy and (108185) 27/11/2019 (Services) With others CM.383- (Maazullah khan barkandi) (A.A.G) p/19(M)(stay), Promotion-Service- Statutory- Promotion Date By Court Constitutional Bench 7 3 W.P 3297-P/2017 Zafar Ali Khan etc V/s The Govt.of KPK through Chief (114454) 20/11/2019 -Legislation-Rules Secretary etc (M. -

Annual Security Report 2020 Table of Contents

ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................................1 Acronyms ..........................................................................................................................................2 Casualties of terror attacks and counter-terror operations ..................................................................3 Victims of terror attacks and counter-terror operations .................................................................... 6 SECURITY OPERATIONS ......................................................................................................................7 Provincial data on security operations ............................................................................................... 7 Nature of security operations ............................................................................................................. 8 Militants, criminals, and foreign spies arrested in 2019 ................................................................... 10 Foreign outlaws and agents arrested during 2019 ........................................................................... 11 TERROR ATTACKS IN 2020 ................................................................................................................ 12 Provincial data of terror attacks ....................................................................................................... 12 Nature