Josephson 1 Global Kodak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Camera – Revealed

PHOTOGRAPHIC CANADIANA Volume 35 Number 2 Sept.– Oct.– Nov. 2009 PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT LANSDALE PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT THE MYSTERY GORDON CAMERA – REVEALED THE PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA PHOTOGRAPHIC CANADIANA JOURNAL OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA Volume 35, Number 2 ISSN 0704-0024 Sept. – Oct. – Nov. 2009 Date of Issue – September 2009 Canada Post Canadian Publications Mail Sales Product Agreement No. 40050299 Postage Paid at Toronto Photographic Canadiana is published four times a year (except July and August) by The Photographic Historical Society of Canada, 6021 Yonge Street, Box 239, Toronto, Ontario, M2M IN THIS ISSUE 3W2 Photographic Canadiana does not pay 2 PC Index 17 Yes Virginia there is a for articles or photographs; all functions Our Cover Gordon Camera of the PHSC are based on voluntary 3 President’s Message –Robert Lansdale and participation. Manuscripts or articles The Society, Executive and Clint Hryhorijiw should be sent to the Editor and will be PC Editorial Board returned if requested. 4 Toronto Notes: April, May and PC Supplement Sheet Views expressed in this publication June 2009 meetings 1 Schedule for September solely reflect the opinions of the au- –Robert Carter thors, and do not necessarily reflect the 2009 views of the PHSC. 6 Browsing through our Exchanges 2 Coming Events & Want Ads –George Dunbar For Back Issues 8 The Melodrama Continues For back issues and single copies: or- as the Vitascope Travels to der directly from the Librarian, whose Toronto and Halifax name and address appear on page 3. –Robert Gutteridge Current copies are $5.00 each. A sub- scription is included in membership fee which is $35.00 a year. -

Kodak-History.Pdf

. • lr _; rj / EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY A Brief History In 1875, the art of photography was about a half a century old. It was still a cumbersome chore practiced primarily by studio professionals and a few ardent amateurs who were challenged by the difficulties of making photographs. About 1877, George Eastman, a young bank clerk in Roch ester, New York, began to plan for a vacation in the Caribbean. A friend suggested that he would do well to take along a photographic outfit and record his travels. The "outfit," Eastman discovered, was really a cartload of equipment that included a lighttight tent, among many other items. Indeed, field pho tography required an individual who was part chemist, part tradesman, and part contortionist, for with "wet" plates there was preparation immediately before exposure, and develop ment immediately thereafter-wherever one might be . Eastman decided that something was very inadequate about this system. Giving up his proposed trip, he began to study photography. At that juncture, a fascinating sequence of events began. They led to the formation of Eastman Kodak Company. George Eastman made A New Idea ... this self-portrait with Before long, Eastman read of a new kind of photographic an experimental film. plate that had appeared in Europe and England. This was the dry plate-a plate that could be prepared and put aside for later use, thereby eliminating the necessity for tents and field processing paraphernalia. The idea appealed to him. Working at night in his mother's kitchen, he began to experiment with the making of dry plates. -

History of KODAK Cameras

CUSTOMER SERVICE PAMPHLET March 1999 • AA-13 History of KODAK Cameras KODAK CAMERAS ON THE MARKET ORIGINAL CAMERA NAME FROM TO FILM SIZE LIST PRICE No. 1A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK 1917 Model Camera 1917 1924 116 $21.00 No. 3 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Camera 1914 1926 118 41.50 No. 3A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Camera 1914 1934 122 50.50 No. 1 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Junior Camera 1914 1927 120 23.00 No. 1A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Junior Camera 1914 1927 116 24.00 No. 2C AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Junior Camera 1916 1927 130 27.00 No. 3A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Junior Camera 1918 1927 122 29.00 No. 1 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1915 1920 120 56.00 (Bakelite side panels) No. 1 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera (Model B) (Back overlaps sides) Focus by thumb-turned gear. 1921 1921 120 79.00 (Only produced for a few months) No. 1 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera (Model B) 1922 1926 120 74.00 (knurled screw focusing) No. 1A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1914 1916 116 59.50 No. 1A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1917 1923 116 91.00 (w/coupled rangefinder and Bakelite side panels) No. 1A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1923 1926 116 60.00 w/coupled rangefinder, Model B (Back overlaps sides) No. 2C AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1923 1928 130 65.00 w/coupled rangefinder No. 3 AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1914 1926 118 86.00 No. 3A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1914 1916 122 74.00 No. 3A AUTOGRAPHIC KODAK Special Camera 1916 1934 122 109.50 (w/coupled rangefinder) Boy Scout KODAK Camera (V.P. -

The Photographic Snapshot

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 3-1-1986 The photographic snapshot Michael Simon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Simon, Michael, "The photographic snapshot" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHOTOGRAPHIC SNAPSHOT by Michael Simon March 1986 Master of Fine Arts Thesis Rochester Institute of Technology Thesis Board Richard D. Zakia Chairman: Richard Zakia, Professor, School of Photographic Arts & Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology Members: Elliott Rubenstein, Associate Professor, School of Photographic Arts & Sciences, Rochester Institute of Technology Keith A. Boas Keith Boas Eastman Kodak Company, Supervising Editor, Commercial Publications 1 CONTENTS Thesis Board 1 Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Snapshots a Definition 4 Photographs as art 6 The ubiqui tousness of the snapshot 12 Survey of past definitions of snapshots 15 A definition of folk art 25 Photographic snapshots as folk art 34 Snapshots and the media 44 Snapshots as ritual 55 The Evolution of the Snapshot since 1880 66 Enjoying Photographs 7 9 Bibliography 103 List of Illustrations 107 Acknowledgements My thesis board, Richard Zakia, Elliott Rubenstein, and Keith Boas, have been of great assistance in the preparation of this essay and have supported my work through its many drafts. For their contribution I owe them many thanks. In addition, I should like to thank all those who helped with comments, suggestions, and who read the manuscript in its many stages. -

Festschrift:Experimenting with Research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman

Science Museum Group Journal Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Jeffrey Sturchio 04-08-2020 Cite as 10.15180; 201311 Research Festschrift: experimenting with research: Kenneth Mees, Eastman Kodak and the challenges of diversification Published in Spring 2020, Issue 13 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311 Abstract Early industrial research laboratories were closely tied to the needs of business, a point that emerges strikingly in the case of Eastman Kodak, where the principles laid down by George Eastman and Kenneth Mees before the First World War continued to govern research until well after the Second World War. But industrial research is also a gamble involving decisions over which projects should be pursued and which should be dropped. Ultimately Kodak evolved a conservative management culture, one that responded sluggishly to new opportunities and failed to adapt rapidly enough to market realities. In a classic case of the ‘innovator’s dilemma’, Kodak continued to bet on its dominance in an increasingly outmoded technology, with disastrous consequences. Component DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201311/001 Keywords Industrial R&D, Eastman Kodak Research Laboratories, Eastman Kodak Company, George Eastman, Charles Edward Kenneth Mees, Carl Duisberg, silver halide photography, digital photography, Xerox, Polaroid, Robert Bud Author's note This paper is based on a study undertaken in 1985 for the R&D Pioneers Conference at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware (see footnote 1), which has remained unpublished until now. I thank David Hounshell for the invitation to contribute to the conference and my fellow conferees and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania for many informative and stimulating conversations about the history of industrial research. -

From the Editor Interstate Search Extended for Prof

Plans ior New Union's Construction • • •f,' Hp! •• From the Editor Hindered by Financial Requirements A day or more of protest... by Joel Siegfried Alfred's present student union er learned that the University is "I know there are many here 7 had no shoes and complained . was erected around 1945 and being retarded in its construction who take a personal Interest in known as Burdick Hall. After ... until I met a man with no feet.- efforts due to a lack of funds <*- Alfred," said Dr. Drake, "and I -anonymous World War n, two prefabricated one hundred and fifty thousand structures were obtained from the would like them to feel free to dollars to be exact. But I still bad no shoes.—bell government, and were attached at discuss their ideas with me." The financial situation is such the western end of the building. What has been done so far to •that the University now holds a The Student Senate has received a letter from the American The entire unit has served as the bring the new union closer to re- donbract for a loan of $300,000 totudejnt union (tor the past ten ality? Many alumni and friends of Committee on Africa asking that the students of Alfred help from the Federal Housing Author- years, and while It has undergone the school have been contacted. iupport their endeavor to stop apartheid in South Africa. The ity. This loan, to be paid by amort- many alterations and additions Groups have been offered, as an following is a paragraph from their letter: ization is at a discount rate of such as the construction of a inducement .to subscribe to the 2.78 per cent. -

Kodak Movie News; Vol. 10, No. 4; Winter 1962-63

PUBLISHED BY EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY W I N T E R 1 9 6 2- 6 3 KODAK MOVIE NEWS Q. I have a roll of KODACHROME Film in my 8mm camera that has been exposed on the first half. I've LETTERS TO lost the carton the film came in and I forgot whether I have KODACHROME or KODACHROME II Film . And I'm not sure whether it's Daylight Type or Type A. Is THE EDITOR there any way I can tell? Mr. C. B., Nashville, Tenn. Comments: I thought you might be interested in an unusual sequence I shot recently. I observed a big snapping turtle come into my yard and, knowing that she was going to dig a hole and lay her eggs, I loaded my camera and took some wonderful shots. I watched the eggs, and 3½ months later when they started to hatch, I made shots of the baby turtles coming out of the eggs and learning to walk. Later I made appropri· ate titles, and came up with what I call a creditable color movie. Mrs. B. E. C., Moorestown, N.J. A. Yes. Take a look at the end of your film. If it's Your seasonal titles are more helpful now that you KODACHROME Fi lm, you will see the legend "KOD print them sideways. At least mine were not creased. HALF EXP " punched through the film ind icating Day- Mr. L. G. P., Philadelphia, Pa. light Type, or " KOD A HALF EXP" if it's Type A. If your roll is KODACHROME II Film, th ere will be Please continue to publish seasonal titles. -

KODACOLOR RDTG Series Inks Datasheet

KODACOLOR RDTG Series Inks High performance with mid/high viscosity inks KODACOLOR RDTG Series System Qualiied Piezo-electric Print Heads The KODACOLOR RDTG Series inks from Kodak FUJI STARFIRE, RICOH GEN 4, RICOH GEN 5 & were speciically developed for direct-to-fabric RICOH GH2220. Formulated with best in class printing on cotton, cotton blends, and polyester components selected to provide market leading, fabrics. They are equally at home when used industrial performance. for printing directly to inished garments or to roll fabrics. This water-based digital ink system is designed to work in printers that employ 14 piezo-electric print heads. Although designed RDTG Viscosity Proile for use in production printing, it is suitable for 12 high quality sampling and strike offs. 10 KODAK RDTG Series performs to the highest level of nozzle performance among Print Heads 8 requiring mid-high viscosity inks. 6 Fabric Pre-Treats The KODACOLOR Pre-Treats are formulated (mPas) Viscosity 4 exclusively for the KODACOLOR EDTG & RDTG Ink Sets to produce the highest quality image 2 and excellent durability in wash-fastness. The 0 three types of Pre-Treat cover the gamut of 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 garments available, from 100% Cotton Dark to Temperature (deg C) White Polyesters. RCDGT RMDGT RYDGT RKDGT RWDGT Powered by KODACOLOR Technology KODACOLOR RDTG Series Inks Micrographs of dot formation KODAK RDTG Series mid-high viscosity Ink set printed through a RICOH GEN 5 Print Head Cyan Black RDTG Viscosity Viscosity Viscosity Viscosity Viscosity Viscosity -

Related Primary Sources

Related Primary Sources Cameras represent the largest collection of technology at the Fulton County A Century of Cameras Schools Archives and Teaching Museum. The assortment spans nearly all @ the decades of the twentieth century and helps explain why so many images of schools, students, teachers, parents and employees are stored in the ar- Teaching Museum South chives and on display in exhibits. Photographs, more than any other audio/ visual medium, have documented the history of the schools and the commu- nities they serve over the past century and a half. Kodak No. 0 0 Model B, 1916 1916.13.110 The Model B represents the simplest of photograph technology. Its initial price was only $1. Invented by Frank A. Brownell, these “Brownies” were widely popular and affordable. How it works: the lens simply allows light into the box, which upon contact with the light-sensitive film, records an image. To develop prints, the camera was brought to a camera dealer, where the film would be removed and processed. Agfa Synchro Box, 1951 1951.50.3 This German-made camera used Kodak 120 film. The front has a large lens and two viewfinders. The viewfinders were connected by mirrors to corresponding lenses on the top and sides to allow for both portrait and landscape-oriented photographs. Exakta VX IIb, 35mm, 1963 1963.18.4 The Exakta was produced by a German company named Ihagee. At the time it was produced, it pro- vided the photographer with all the newest up- grades in camera technology, including inter- changeable lenses and stereo viewfinder attach- ments. -

Manual Kodak Easyshare Z712is

Manual Kodak Easyshare Z712is Get support for Kodak Z712 - EASYSHARE IS Digital Camera. UPC - Need To Download Manual For Easyshare Z712 Is. Easy Or Free Way? (Posted. View and Download Kodak EasyShare Z885 user manual online. Kodak EasyShare Z885: Kodak user's guide digital camera easy share z712 is (75 pages). Get Kodak Z712 - EASYSHARE IS Digital Camera manuals and user guides Kodak EasyShare Z712 IS zoom digital camera User's guide kodak.com For. The Kodak EasyShare V570 was a high-end digital camera manufactured by ISO equivalent 64– 160 (auto) and 64, 100, 200, 400, 800 (1.8MP) (manual) Kodak Z612 Zoom Digital Camera · Kodak Z712 IS ZOOM digital camera · Starmatic. kodak camera m1063 manual kodak easyshare repair manual kodak easyshare kodak easyshare c813 manual kodak easyshare z712is instructions kodak. Manual is very complicated with respect to a custom reset. Kodak EasyShare C875 Kodak EasyShare Z712 IS Kodak EasyShare Z885 Olympus C-8080 Wide. Manual Kodak Easyshare Z712is Read/Download Kodak Z740 Manual Online: Pasm Modes. Kodak easyshare user's guide digital camera z740. Digital Camera Kodak EasyShare Z712 IS Specifications. Find a kodak easyshare in United Kingdom on Gumtree, the #1 site for Digital Used kodak easy share Z712 IS digital camera 7.1mp, 12x optical zoom, optical IS charger and 4gb sd memory card Instruction Manual cable a/v usb wire. Kodak EASYSHARE Z7121s - Z712 IS Digital Camera Free Kodak Z712 manuals! Where Can I Buy A Lens Cap For My Kodak Easyshare Z712 Is Digital. New listing Battery Charger for KODAK EasyShare Z612 Z712IS Z812 IS K8500 KLIC-8000 Kodak EasyShare Digital Camera Manual Guide Z ZD Series. -

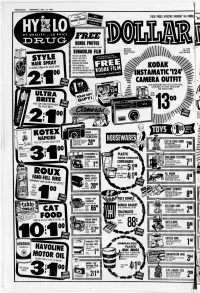

"POX PAL WAGON KODAK COASTER MODEL NO M Firl ENGINE RED Enamtl MOVIE OUTFIT FINISH RUBBER TIRES

PRESS-HERALD WEDNESDAY, NOV. 13, 1968 THESE PRICES EFFECTIVE THURSDAY thru SUNDtJf BONUS PHOTOS WHtN YOU BRING US YOUR SQUARL PICTURE ALL ITEMS LIMITED TO KODACOLOR FILM STOCK ON HAND YOU GET AN EXTRA STYLE WALLET SIZE PHOTO ALONG WITH EACH REGULAR SIZE ALBUM HAIR SPRAY PHOTO WITH ALL 13 OUNCE CAI^-«79c VALUE EACH KODAK INSTAMATIC 126 FILM (12 OR 20 EXPOSURES! OR 12 00 AND 620 KODACOLOP FILM INSTAMATIC 124' CAMERA OUTFIT PLUS KODACOLOR X FILM FOR 12 COLOR SNAPS, FLASHCUBES. BATTERIES. WRIST STRAP AND INSTRUCTIONS! ULTRA BRITE nd ACCESSORIES KODAK KOTEX Instamatic314 NAPKINS COLOR OUTFIT PKG. OF 12 *49c VALUE EACH LOST IN SPACE ROBOT M V ,'fO ROBOT Tt'M VOVES AROUND YilTH L'GMts FLASHING. HIS ARMS MOVL t POINT. 9.95 VALUE , FUSHCUBES or PLASTIC FLASHBULBS FOOD STORAGE JUNGLEBOOK TELEPHONE SYLVAN IA Mil M AC18 WALT OISNIV S 12 HASH TALKING TELEPHONE THEY PACKS CONTAINERS 1ALK TO YOU. JUST TURN IHE VAlUtS DIAL. 895 VAIUE ... ...... TO ? n .... I t» "POX PAL WAGON KODAK COASTER MODEL NO M FIRl ENGINE RED ENAMtl MOVIE OUTFIT FINISH RUBBER TIRES. 6 95 VALUE INSTAMATIC M MM. JOHNNY TOYMAKER MA'S'', All K'NDS 01 TlNG TOYS. CARS. TRUCKS AM ulHfRS S(T INCLUDES EVEHYIHINC YOU NEED. POLY BOWLS 12 95 VALUE LOVIN1 LEAVES. 120 OZ. 1.39 VAl BONGO BASKET KER-PLUNK GAME II QT, POlYrFMYUNf. 169 VAL. CAT TRAYMATES DEKA. PIASTIC. 13'i"illH"i2»»" FOOD 1 39 VALUE SKITILE-BOWl TIN PiS ACTION GAME SCORF.S UK( BOWLING FUN Fufl IHE WHOLE FAMILY 12 9i VALUE IHE GAME THAT MAXES YOU Kodacolor '126' THINK WHILE HAVING FUN. -

HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras

· V 1965 SPRING SUMMER KODAK PRE·MI MCATALOG HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Cameras ... No. C 11 SMP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Flasholder For "bounce-back" offers where initial offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Creates additional sales, gives promotion longer life. Flash holder attaches eas ily to top of Hawkeye Instamatic camera. Makes in door snapshots as easy to take as outdoor ones. No. ASS HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Camera A great self-liquidator. Handsomely styled in teal green and ivory with bright aluminum trim. Hawkeye Instamatic camera laads instantly with No. CS8MP HAWKEYE INSTAMATIC Field Case film in handy, drop-in Kodapak cartridges. Takes black-and-white and Perfect choice for "bounce-back" offers where initial color snapshots, and color slides. Extremely easy to use .• • gives en offer was the Hawkeye Instamatic camera or Hawkeye joyment to the entire family. Available in mailer pack. May be person Instamatic F camera. Handsome black simulated alized on special orders with company identification on the camera, either leather case protects camera from dirt and scratches, removable or affixed permanently. facilitates carrying. Supplied flat in mailing envelope. 3 STEPS 1. Dealer load to your customers. TO ORGANIZING Whether your customer operates a supe- market, drug store, service station, or 0 eo" retail business, be sure he is stocked the products your promotion will feo 'eo. AN EFFECTIVE Accomplish this dealer-loading step by fering your customer additional ince .. to stock your product. SELF -LIQUIDATOR For example: With the purchase of • cases of your product, your custo mer ~ ceives a free in-store display and a HA PROMOTION EYE INSTAMATIC F Outfit.