Downloaded License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter - January 2020

WalkingSupport - Newsletter - January 2020 Best Wishes for the New Year This is the time of year when many walkers start to look to the spring and summer to consider how they might get out and enjoy the countryside after what has been a wet and somewhat dismal winter. We hope that as the days start to lengthen the opportunity to get out and enjoy some of the many walking routes will become a reality. Walking Support extends our best wishes for 2020 to all our past, present and future clients. Special Offer 15% Reduction on our planning and booking fees for 2020 walks if your requirement is confirmed prior to the end of February 2020. Walking Support is a one stop planning and booking business for self led walks on the following long distance routes: Great Glen Way Rob Roy Way Cateran Trail West Highland Way Fife Coastal Path Forth Clyde and Union Canals Southern Upland Way – Sir Walter Scott Way Borders Abbeys Way St Cuthbert’s Way St Oswald’s Way Northumberland Coastal Path Hadrian’s Wall Path – Roman Heritage Way Weardale Way Deeside Way For fuller details simply link to our website home page www.walkingsupport.co.uk. Walking Support will provide you with an outline plan and cost estimate before there is any commitment to use our services. All packages are tailor made to the clients requirements, we do not offer standard off the shelf walking holidays*. To visit comprehensive websites on almost all of the above walking routes simply click on www.walkingsupport.co.uk/routes.html and highlight the one that is of immediate interest. -

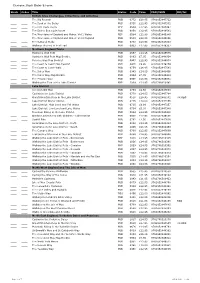

Cicerone Stock Order & Form

Cicerone Stock Order & Form Stock Order Title Status Code Price EAN/ISBN UK/Int British Isles Challenges, Collections and Activities ____ ____ The Big Rounds PUB 0772 £18.95 9781852847722 ____ ____ The Book of the Bothy PUB 0756 £12.95 9781852847562 ____ ____ The C2C Cycle Route REP 0649 £12.95 9781852846497 ____ ____ The End to End Cycle Route PUB 0858 £12.95 9781852848583 ____ ____ The Mountains of England and Wales: Vol 1 Wales REP 0594 £12.99 9781852845940 ____ ____ The Mountains of England and Wales: Vol 2 England PUB 0589 £12.99 9781852845896 ____ ____ The National Trails PUB 0788 £18.95 9781852847883 ____ ____ Walking The End to End Trail PUB 0933 £17.95 9781852849337 Northern England Trails ____ ____ Hadrian's Wall Path PUB 0557 £14.95 9781852845575 ____ ____ Hadrian's Wall Path Map Booklet PUB 0893 £7.95 9781852848934 ____ ____ Pennine Way Map Booklet PUB 0907 £12.95 9781852849078 ____ ____ The Coast to Coast Map Booklet PUB 0926 £9.95 9781852849269 ____ ____ The Coast to Coast Walk PUB 0759 £16.95 9781852847593 ____ ____ The Dales Way PUB 0943 £14.95 9781852849436 ____ ____ The Dales Way Map Booklet PUB 0944 £7.95 9781852849443 ____ ____ The Pennine Way PUB 0906 £16.95 9781852849061 ____ ____ Walking the Tour of the Lake District NYP 1049 £14.95 9781786310491 Lake District ____ ____ Coniston Old Man PUB 0763 £2.50 9781852847630 ____ ____ Cycling in the Lake District PUB 0778 £14.95 9781852847784 ____ ____ Great Mountain Days in the Lake District PUB 0516 £18.95 9781852845162 UK REG ____ ____ Lake District Winter Climbs PUB 0716 -

Teviot Wind Farm EIA Scoping Report

Muirhall Energy Ltd Teviot Wind Farm EIA Scoping Report Prepared by LUC March 2021 Muirhall Energy Ltd Teviot Wind Farm EIA Scoping Report Project Number 11283 Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. First draft for client review L. Meldrum J. Wright J. Wright 26.02.2021 K. Jukes D. McArthur nd 2. 2 draft for client review K. Jukes J. Wright J. Wright 17.03.2021 D. McArthur L. McGowan rd 3. 3 draft for client review D. McArthur J. Wright J. Wright 26.03.2021 K. Jukes 4. Minor amendments to V3 D. McArthur J. Wright J. Wright 30.03.2021 L. Cargill 5. Final draft D. McArthur J. Wright J. Wright 31.03.2021 Bristol Land Use Consultants Ltd Landscape Design Edinburgh Registered in England Strategic Planning & Assessment Glasgow Registered number 2549296 Development Planning London Registered office: Urban Design & Masterplanning Manchester 250 Waterloo Road Environmental Impact Assessment London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment landuse.co.uk Landscape Management 100% recycled paper Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents Teviot Wind Farm March 2021 Contents Design Considerations 20 Chapter 1 Proposed Surveys and Assessment Methodologies 21 Introduction 1 Potential Significant Effects 27 Muirhall Energy Limited 2 Effects Scoped Out 28 Consultation and Next Steps 2 Approach to Mitigation 28 Document Structure 2 Questions 28 Chapter 2 Chapter 6 The Environmental Impact Assessment 4 Geology, Hydrology, Hydrogeology and Peat 29 Scoping 4 Baseline Conditions 5 Introduction 29 Assessment of Effects 5 Existing Conditions -

Cicerone-Catalogue.Pdf

SPRING/SUMMER CATALOGUE 2020 Cover: A steep climb to Marions Peak from Hiking the Overland Track by Warwick Sprawson Photo: ‘The veranda at New Pelion Hut – attractive habitat for shoes and socks’ also from Hiking the Overland Track by Warwick Sprawson 2 | BookSource orders: tel 0845 370 0067 [email protected] Welcome to CICERONE Nearly 400 practical and inspirational guidebooks for hikers, mountaineers, climbers, runners and cyclists Contents The essence of Cicerone ..................4 Austria .................................38 Cicerone guides – unique and special ......5 Eastern Europe ..........................38 Series overview ........................ 6-9 France, Belgium, Luxembourg ............39 Spotlight on new titles Spring 2020 . .10–21 Germany ...............................41 New title summary January – June 2020 . .21 Ireland .................................41 Italy ....................................42 Mediterranean ..........................43 Book listing New Zealand and Australia ...............44 North America ..........................44 British Isles Challenges, South America ..........................44 Collections and Activities ................22 Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland .......44 Scotland ................................23 Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania ....45 Northern England Trails ..................26 Spain and Portugal ......................45 North East England, Yorkshire Dales Switzerland .............................48 and Pennines ...........................27 Japan, Asia -

Ranger Led Activities and Paths to Health Walk It Walks

2013-2014 Ranger led Activities and Paths to Health Walk It Walks Scottish Borders Council Ranger Service/ Paths to Health - Walk It Walking Project Environment and Infrastucture, Council HQ Newtown St Boswells MELROSE TD6 OSA Tel: 01835 826750 email :[email protected] [email protected] web www.scotborders.gov.uk/walking BOOKING For most of the activities listed in this pamphlet there is no need to book in advance. Where booking is required this is stated in the description for the event. STARTING AND FINISHING Starting times for the events will be strictly adhered to, but finishing times are approximate. The starting points are indicated by a six figure grid reference. Where the walks are linear, transport may be arranged or the walk may fit in with public transport. Where possible for these linear walks walkers are encouraged to use the public transport suggested. The approximate time involved for each activity is given in the programme. The leader will turn out irrespective of weather conditions. The decision whether or not to proceed with the event will be made at that time. DOGS Please note that dogs are not allowed on any of our walks or events due to the likelihood of encountering cattle or livestock with young. TYPE OF ACTIVITY WALK The WALKS are not too rough, but will be wet on occasions and inclement weather may worsen conditions. Participants are advised to come adequately shod and clothed, and Wellingtons or boots may be advisable on wet days. On most WALKS no packed lunches will be required. The WALKS are not hikes and are designed for family groups and for all ages and abilities. -

2021 Brochure

RR2021leafletA4PortraitMar30.qxp_Layout 1 31/03/2021 15:17 Page 1 Award-winning guidebooks Lightweight, weatherproof, with detailed maps of 26 walks across Britain Moffat to Circuit from Circuit from Circuit from Helmsley St Bees to Ulverston Ilkley to Bowness- Kincardine Solway Firth Brodick Melrose Blairgowrie to Filey Robin Hood’s Bay to Carlisle on-Windermere to Newburgh 56 miles 90 km 65 miles 105 km 67 miles 108 km 64 miles 103 km 108 miles 174 km 184 miles 296 km 73 miles 118 km 79 miles 127 km 117 miles 187 km A Scottish coast-to-coast route North Berwick Fort William Bowness-on-Solway Circuit from Helensburgh Tarbert to St Ives to Loch Fyne to Forres to Lindisfarne to Inverness to Wallsend Cheltenham to Dunbar Machrihanish Penzance Loch Lomond to Cullen 70 miles 112 km 77 miles 124 km 86 miles 138 km 94 miles 151 km 134 miles 215 km 100 miles 161 km 42 miles 68 km 57 miles 92 km 44 miles 70 km Circuit from Drymen to Settle to Circuit in Winchester Buckie Melrose to North Glasgow www.rucsacs.com Pateley Bridge Pitlochry Carlisle Snowdonia to Eastbourne to Aviemore Lindisfarne to Fort William for guidebooks on 54 miles 87 km 77 miles 124 km 97 miles 156 km 83 miles 134 km 100 miles 160 km 80 miles 128 km 62 miles 100 km 95 miles 154 km walks in Ireland For more about books published by Rucksack Readers : www.rucsacs.com +44/0 131 661 0262 1 Annandale Way 9781898481751 £12.99 2017 14 John Muir Way 9781898481836 £14.99 2018 15 2 Arran Coastal Way 9781898481799 £12.99 2018 Kintyre Way 9781898481812 £12.99 2018 18 24 3 Borders Abbeys -

Appendix 2 Response by Scottish Borders Council to the Payphones

Appendix 2 Response by Scottish Borders Council to the Payphones Closure Consultation The consultation process being carried out by British Telecom has indicated that there are currently 46 public payphones which are little used by consumers and are proposed for closure. In addition it is understood that there was one additional payphone in the Newcastleton area that was included in the list of payphone closures for North Cumbria. Payphones provide an important communications ‘safety net’ for individuals within communities in the Scottish Borders. This is especially the case where: x There is restricted mobile phone coverage by the four national mobile phone operators (which is a major concern), x There are tourists or visitors passing through country areas and where there maybe a need communicate problems resulting from accidents, crime or other issues x There is social need. The payphones most affected by these criteria are shown below. All of these are in social need. There is also reference to payphones where particular concerns have been raised by communities. It is the Council’s view that all of the payphones referred to below should be kept open. Restricted Mobile Coverage In Relation to National Mobile Telephone Operators x Pco, Longformacus, Duns TD11 3PE - Tel No 01361 890220 (representation from the Cranshaws, Ellemford and Longformacus Community Council on this proposed closure) x Pco, (Ellemford, Longformacus) Duns TD11 3SG – Tel 01361 890270 (representation from the Cranshaws, Ellemford and Longformacus Community Council on this proposed closure) x Pco1 Craik, Hawick TD9 7PS – Tel 01450 880232 (representation from Upper Teviotdale and Borthwick Community Council on this proposed closure.) - Craik is a forest area. -

1021 INDEX 30 St Mary Axe Building 81, 174 a a La Ronde 357 Abbey

© Lonely Planet Publications 1021 Index 30 St Mary Axe building 81, 174 Aberystwyth 741-4, 743 Greenwood Forest Park 771 ABBREVIATIONS abseiling Heights of Abraham 461 A ACT Australian Capital Brecon Beacons National Park 724 Pleasure Beach 601 Territory A La Ronde 357 Cairngorms National Park 909 Puzzle Wood 269 NSW New South Wales Abbey Road Studios 170 Cheddar Gorge Caves 342 Sandcastle Waterpark 601 NT Northern Territory abbeys, see also churches & cathedrals, Isle of Arran 844 An T-Àth Leathann 941 Qld Queensland monasteries Lochmaddy 949 Anderson, Arthur 967 SA South Australia Abbey Church of St Mary the Snowdonia National Park 764 Anfield Stadium 594 Tas Tasmania Virgin 310 accommodation 982-5, see also Angel of the North 648-9, 4 Vic Victoria Arbroath Abbey 892 individual locations Anglesey Model Village & Gardens 773 WA Western Australia Bath Abbey 331 Achavanich Standing Stones 927 Anglo-Saxon people 38, 40 Battle Abbey 220-1 Achiltibuie 932 animals 101-3, see also individual Beaulieu 293 Achnabreck 853 animals, wildlife sanctuaries Buckland Abbey 365 activities 108-26, see also individual books 101 Bury St Edmunds 421 activities internet resources 103 Byland Abbey 564 Acts of Union 48, 51, 53, 54 Anne Hathaway’s Cottage 488 Calke Abbey 460 Admiralty Arch 153 Anstruther 878-9 Dryburgh Abbey 830-1 air pollution 106 Applecross 934-5 Dunfermline Abbey 880 air travel aquarius Egglestone Abbey 654 airlines 997 Aquarium of the Lakes 615 INDEX Fountains Abbey 554 tickets 997 Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) 376 Glastonbury Abbey 343 to/from -

John Muir Way Visitor Survey 2014-2015

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 918 John Muir Way visitor survey 2014-2015 COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 918 John Muir Way visitor survey 2014-2015 For further information on this report please contact: Aileen Armstrong Scottish Natural Heritage Great Glen House Leachkin Road INVERNESS IV3 8NW Telephone: 01463 725305 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Stewart, D., Wilson, V., Howie, F. & Berryman, B. 2016. John Muir Way visitor survey 2014-2015. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 918. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage Year 2016. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary John Muir Way visitor survey 2014-2015 Commissioned Report No. 918 Project No: 15191 Contractor: TNS Year of publication: 2016 Keywords John Muir Way; Long Distance Routes; Scotland’s Great Trails; visits to the outdoors; participation in outdoor recreation; physical activity in the outdoors. Background This report presents the findings from the John Muir Way visitor survey, commissioned in 2014 by Scottish Natural Heritage. The report provides a baseline estimate of usage of the route and insights into the profile of users, visitors’ experiences and their level of awareness of this route and other long distance routes in Scotland. The research findings presented in this report are based on manual counts and face to face interviews undertaken with a sample of 537 visitors at various locations along the entire length of the route between November 2014 and October 2015. -

Walking the Borders Abbeys Way, 2017

Walking the Borders Abbeys Way, 2017 By Christine McNaughton My friend, and regular walking companion, Marjorie have, over the past few years, walked several long-distance routes. For 2017 we decided on The Borders Abbeys Way, a 68 mile-long route linking the abbey towns in the Scottish Borders. We decided to make Melrose our base for the week so booked into a hotel along with my husband John and several friends. L to R: John & Christine McNaughton & Marjorie at Melrose Abbey. The Temple of the Muses. Day 1: On the first day we drove up to Melrose in the morning, and after registering at the hotel, we made our way to Melrose. The Abbey was founded in 1136 by the monks of the Cistercian Order at the request of David I of Scotland and several Scottish Kings are buried there. In 1921 a lead container believed to hold the embalmed heart of Robert the Bruce was found under the Chapter House. From here we would walk the six miles to Dryburgh Abbey. John walked with us on this section, and after going along the ancient Priors Walk (a route used by the masons during the building of the Abbey) we reached the Rhymer’s Stone. This marks the place where the Eildon Tree once stood, and where Thomas Rhymer is said to have met the Queen of Fairies and delivered prophecies in the 13th century. A few miles on we made a small detour to see the Temple of the Muses. This circular neo-classical “temple” is dedicated to James Thompson (1700-1748) poet, and was erected by David Stuart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan. -

ZTV Figure 5.1.2A Cloich Forest Wind Farm EIA Report

275000 280000 285000 290000 295000 300000 305000 310000 315000 320000 325000 330000 335000 340000 345000 350000 355000 360000 365000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 9 6 6 Notes The ZTV is calculated to turbine tip height (149.9 m) from a viewing height of 2 m above ground level. 0 0 0 0 0 The terrain model assumes bare ground and is 0 5 5 8 8 6 derived from OS Terrain 50 height data 6 (obtained from Ordnance Survey in July 2019). Earth curvature and atmospheric refraction 0 have been taken into account. 0 0 0 0 0 0 The ZTV was calculated using ArcMap 10.5.1 0 8 8 6 software. 6 Site boundary 0 0 0 0 0 0 ! 5 5 Turbine location 7 7 6 6 5 km intervals from outermost turbines 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 7 40 km interval from outermost 6 6 turbine «¬ 0 0 Viewpoint location 0 0 0 0 5 5 6 6 6 6 National Cycle Network (NCN) «¬ VP22 NCN Link 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 Annandale Way 6 6 Borders Abbeys Way 0 0 0 0 0 0 Clyde Walkway C U 5 «¬ 5 5 VP26 5 L ¬ 6 « 6 , «¬ VP21 s VP13 A Cross Borders Drove Road L , «¬ A VP12 «¬ VP7 W D Fife Coastal Path 0 0 L ¬ « 0 VP24 0 , 0 0 s 0 0 n «¬ 5 VP8 5 a «¬ r 6 6 t ! ¬ Forth Clyde Canal/Union Canal s « !! VP3 VP9 u «¬ VP20 S ! , ! ! «¬ VP6 H «¬ !! ! John Muir Way N VP18 «¬ ! S ¬ ! « 0 VP1 ! 0 , VP10 F 0 0 0 0 D 5 5 E «¬ «¬ River Ayr Way VP17 4 VP2 4 : 6 6 e c r u o «¬ «¬ Romans and Reivers Route S VP4 VP5 5 km . -

SOUTHERN UPLAND WAY W 2Nd Edition Including 8 New Walks Introduction

s on the Eastern Section of lk a THE SOUTHERN UPLAND WAY w 2nd edition including 8 new walks Introduction The Scottish Borders is a beautiful area, full of history and interest, which deserves to be enjoyed by more people. One of the aims of Scottish Borders Council is to encourage tourism to the area and to enable the public to gain access to and learn more about the countryside. This booklet contains descriptions for 55 walks in the Scottish Borders, along with information on features and places of interest that you may come across whilst out walking. Each walk incorporates a part of the Southern Upland Way. The main route is waymarked throughout its length using the standard symbol for Long Distance Footpaths in Scotland. Other sections of the walks may not be waymarked and although this booklet contains maps of the walks, you are strongly recommended to carry the relevant 1:50,000 or 1:25,000 maps for each walk. The official guide for the route offers exceptionally good value as it provides written information for the route and also includes full 1:50,000 map coverage of the entire route. Acknowledgements This booklet has been produced, within the Countryside section of the Planning and Economic Development Portfolio of the Council. Scottish Borders Council is pleased to acknowledge financial support from Scottish Natural Heritage, which greatly assisted the production of this guide. The Council would also like to thank all those individuals, too numerous to mention by name, involved in the production of this booklet. Grateful thanks are extended to all the land owners and land managers for their co-operation and assistance in allowing the walks over their ground to be included.