John Muir Way Visitor Survey 2014-2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiv Crativ Workspac Studios

FIV CR ATIV WORKSPAC EastWorks is a cutting edge new development that will completely transform the disused Purifier Shed in Dalmarnock, Glasgow into high quality, contemporary office / studio accommodation. The former Purifier Shed is one of just STUDIOS five historic buildings to remain in the area and the regeneration plan seeks to safeguard the Victorian listed façade and revitalise the location. The existing roof structure and columns will be exposed and celebrated. A new steel structure will be installed to support mezzanine levels and open flexible floor space with expanses of curtain wall glazing. The listed façade at the rear will boast original features such as decorative sandstone arches around the windows. The final product will deliver the refurbishment of interesting and innovative spaces, which will comprise 5 standalone units / studios / offices. The building was originally known as the Dalmarnock Purifier Shed developed in the late 1800s. It was opened I for various uses and finally closed in the 1950’s. Since then the building has lain vacant until recently when it was I D ST. supported by the Glasgow 2018 European Championships > 1843 for young people to use the area for an Art Festival. DORA STREET / GLASGOW W ll WORTH IT WelLBEING Provision - Dedicated modern accessible shower facilities, high quality changing areas, drying rooms with benches and hooks, lockers, WCs including accessible toilet located at both ground and mezzanine levels with high quality finishes - Service tails for future tea point/kitchen installation - 26 car spaces including 3 accessible spaces - Electric car charging points - Ample cycle parking provided - External bench seating and soft landscaping for relaxation areas Open plan office areas with Mezzanine levels in each unit. -

NEW Coastal Path Leaflet March 2018 Layout 1 09/04/2018 12:00 Page 1

NEW Coastal Path Leaflet March 2018_Layout 1 09/04/2018 12:00 Page 1 About Fife Coast and Countryside Trust We are a local charity committed to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to experience Fife’s great outdoors. We do this through careful management in a manner which respects the balance between people and nature. We manage sites and paths throughout the Kingdom of Fife. For more information, visit our website. fifecoastandcountrysidetrust.co.uk Useful Contacts Coastal Path Information 01592 656080 Fife Council 03451 550000 Traveline 0871 2002233 Your chance to explore Police Scotland 101 Emergency Services 999 There is so much to for you to discover on the Fife Coastal Path. Stretching for over 117 miles from the Forth Estuary in the South, to the Tay Estuary in the North, the route offers a range of walking experiences from easy and level to more challenging and remote. The Coastal Path is one of Scotland’s Great Trails and is part of Fife’s Core Path Network, giving greater access to our greenspaces and linking neighbouring communities. The journey will also give you a chance to visit many of Scotland's award winning beaches close to the route of the path. Why not stop and relax on the sands? Or spend a while exploring rock pools on Fife’s Fringe of Gold. The Fife Coastal Path is part of a living and working landscape with The entire route of the Coastal Path is highlighted with regular many parts owned and managed by private landowners. In the spirit of waymarkers and finger posts and most of the route, villages responsible access, please follow the Scottish Outdoor Access Code. -

A96 Dualling Programme

A96 Dualling Programme Strategic Environmental Assessment Tier 2 Environmental Report An agency of Buidheann le May 2015 An agency of Buidheann le A96 Dualling Programme Strategic Environmental Assessment Tier 2 Environmental Report Document: TSEA96/ER/02 Transport Scotland May 2015 A96 Dualling – Strategic Environmental Assessment – Tier 2 – Environmental Report Document history A96 Dualling Programme Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Tier 2 Environmental Report Transport Scotland This document has been issued and amended as follows: Approved Version Date Description Created by Verified by by 1.0 January 2015 Discussion Draft Susan Rodger/ Henry Collin John Fox Gwenn Greenwood 1.1 April 2015 Draft for Client Comment Ailsa Collin / Gwenn Henry Collin John Fox Greenwood / Henry Collin 1.2 May 2015 Issue Version Ailsa Collin / Gwenn Henry Collin John Fox Greenwood / Henry Collin A96 Dualling – Strategic Environmental Assessment – Tier 2 – Environmental Report Limitations Halcrow Group Ltd, now known as CH2M HILL, has been instructed to provide a Strategic Environmental Assessment of the A96 Dualling Programme on behalf of Transport Scotland. The assessment is based on the information that has been made available at the time of publication and this Environmental Report is presented as a consultation document. Any subsequent additional information arising during the public consultation period may require revision or refinement of the conclusions. It should be noted that: • The findings within this report represent the professional opinion of experienced environmental scientists, sustainability consultants and other specialists. CH2M HILL does not provide legal advice and the advice of lawyers may also be required. • All work carried out in preparing this report has utilised and is based upon CH2M HILL’s professional knowledge and understanding of current relevant European Union, UK and Scottish standards and codes, technology and legislation. -

South Lanarkshire Core Paths Plan Adopted November 2012

South Lanarkshire Core Paths Plan Adopted November 2012 Core Paths list Core paths list South Lanarkshire UN/5783/1 Core Paths Plan November 2012 Rutherglen - Cambuslang Area Rutherglen - Cambuslang Area Map 16 Path CodeNorth Name Lanarkshire - Location Length (m) Path Code Name - Location LengthLarkhall-Law (m) CR/4/1 Rutherglen Bridge - Rutherglen Rd 360 CR/27/4 Mill Street 137 CR/5/1 Rutherglen Rd - Quay Rd 83 CR/29/1 Mill Street - Rutherglen Cemetery 274Key CR/5/2 Rutherglen Rd 313 CR/30/1 Mill Street - Rodger Drive Core233 Path CR/5/3 Glasgow Rd 99 CR/31/1 Kingsburn Grove-High Crosshill Aspirational530 Core Path Wider Network CR/5/4 Glasgow Rd / Camp Rd 543 CR/32/1 Cityford Burn - Kings Park Ave 182 HM/2280/1 Cross Boundary Link CR/9/1 Dalmarnock Br - Dalmarnock Junction 844 CR/33/1 Kingsheath Ave 460 HM/2470/1 Core Water Path CR/9/2 Dalmarnock Bridge 51 CR/34/1 Bankhead Road Water122 Access/Egress HM/2438/1 CR/13/1 Bridge Street path - Cambuslang footbridge 56 CR/35/1 Cityford Burn Aspirational164 Crossing CR/14/1 Clyde Walkway-NCR75 440 CR/36/1 Cityford Burn SLC276 Boundary Neighbour Boundary CR/15/1 Clyde Walkway - NCR 75 1026 CR/37/1 Landemer Drive 147 North Lanarkshire HM/2471/2 CR/15/2 NCR 75 865 CR/38/1 Landemer Drive Core Path93 Numbering CR/97 Land CR/15/3 Clyde Walkway - NCR 75 127 CR/39/1 Path back of Landemer Drive 63 UN/5775/1 Water CR/16/1 Clydeford Road 149 CR/40/1 Path back of Landemer Drive CL/5780/1 304 W1 Water Access/Egress Code CR/17/1 Clyde Walkway by Carmyle 221 CR/41/1 King's Park Avenue CL/3008/2 43 HM/2439/1 -

Fife Coastal Path Final Report

Fife Coast and Countryside Trust Usage and Impact Study – Fife Coastal Path Final Report JN: 145629 Date: December 2007 © 2006 TNS UK Limited. All rights reserved Content 1. Executive Summary........................................................................................... 3 2. Acknowledgements............................................................................................ 5 3. Synopsis ............................................................................................................ 6 4. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 13 4.1 Background ............................................................................................... 13 4.2 Survey Objectives ..................................................................................... 13 4.3 Survey Methodology.................................................................................. 14 5. Results............................................................................................................. 17 5.1 Survey of path users ................................................................................. 17 5.2 Estimate of total number of visits per year ................................................ 54 5.3 Estimates of economic benefits................................................................. 56 5.4 Focus groups with local people ................................................................. 59 5.5 Survey of the Scottish population............................................................. -

Feasibility Study for a Proposed Scottish Borders National Park 16

2017 | Feasibility study for a proposed Scottish Borders National Park 16 Feasibility study for a proposed Scottish Borders National Park First Bus © VisitScotland/Paul Tomkins Bluebells near Minto © Malcolm R Dickson Grass sledging at Born in the Borders © Duncan Bryden Prepared by Duncan Bryden – Bryden Associates 2017 | Feasibility study for a proposed Scottish Borders National Park 17 5. Todiscusstheprosandconsofwhere,in principle,theboundariesmightlie,andthe consequencesofincludingorexcluding 1 thetownsintheareawithinthedesignated NationalPark. Introduction 6. Togiveapreliminaryassessmentof proceduresandpossibletimescalesfor legislatingforandthenprocuringand implementingaproposedScottishBorders NationalPark. 7. Toadequatelyaddressthepointsraisedby ScottishBordersCouncil(seeAppendix7) andindicatewhereinthestudythesepoints are addressed. 1.3 Nonamehasbeenagreedfortheprojectand termslikeBordersNationalParkorSouthern 1.1 Thisindependentstudyhasbeen BordersNationalParkareworkingtitles.Itis commissionedbytheCampaignforaScottish acceptedthat‘AScottishBordersNational Borders NationalParktoexaminetheevidence Park’maybethenamethatdeliversthe forandfeasibilityoftheproposalthatanarea greatestbenefitstothewholearea. oftheScottishBordersbeformallyconsidered fordesignationasanewNationalPark. 1.4 Themapaccompanyingthestudybrief coversaproposedNationalParkareaof 1.2 TheCampaignforaScottishBordersNational approximately1000km2inthesouthern Parkidentifiedsevenobjectivesforthisstudy. sectionoftheScottishBordersCouncilarea comprisingTeviotandLiddesdale,Cheviot -

Chapter 6 Landscape and Visual

Chapter 6 Landscape and Visual www.scottishpowerrenewables.com Clauchrie Windfarm December, 2019 Environmental Impact Assessment Report Table of contents 6.4.5.2 Visualisations 18 6.5 Baseline Conditions 18 6.5.1 Introduction 18 6.1 Introduction 6 6.5.2 Landscape Baseline - Overview 18 6.1.1 Background 6 6.5.2.1 Site Context 18 6.1.2 The proposed Development 6 6.5.2.2 Landscape Character 18 6.1.3 Study Area 6 6.5.2.3 Landscape Designations 19 6.5.2.4 Merrick Wild Land Area (WLA) 19 6.2 Legislation, Policy and Guidelines 7 6.5.3 Visual Baseline Overview 19 6.2.1 Legislation 7 6.5.3.1 Blade Tip ZTV 19 6.2.2 Policy 7 6.5.3.2 Blade Tip ZTV with Potential Forestry Screening 20 6.2.2.1 European Landscape Convention (ELC) 7 6.5.3.3 Hub Height ZTV 20 6.2.2.2 National Planning Framework 3 (NPF3) 7 6.5.3.4 Horizontal Angle ZTV 20 6.2.2.3 National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) 7 6.5.3.5 Overview of Principal Visual Receptors 20 6.2.2.4 Scottish Planning Policy (SPP) 7 6.5.3.5.1 Settlement 20 6.2.2.5 SNH Spatial Planning for Onshore Wind Turbines 7 6.5.3.5.2 Roads 21 6.2.2.5.1 National Scenic Areas 7 6.5.3.5.3 Rail Routes 21 6.2.2.5.2 Gardens and Designed Landscapes 8 6.5.3.5.4 Ferry Routes 21 6.2.2.5.3 Wild Land 8 6.5.3.5.5 Recreational Routes 21 6.2.2.6 South Ayrshire Local Development Plan Policy 8 6.5.3.5.5.1 Southern Upland Way (SUW) 21 6.2.2.6.1 LDP Policy: Landscape Quality 8 6.5.3.5.5.2 Other Long-Distance Footpaths 21 6.2.2.6.2 LDP Policy: Protecting the Landscape 8 6.5.3.5.5.3 Local Paths Network 21 6.2.2.6.3 LDP Policy: Dark Skies 8 6.5.3.5.5.4 -

To Download Barrel Law Non-Technical Summary

Barrel Law Wind Farm Non-technical Summary ABO Wind INTRODUCTION PROJECT DESCRIPTION ABO Wind UK Ltd (ABO Wind), on behalf of Barrel Law Windfarm Ltd, is seeking planning permission to develop Barrel Law Wind Farm (the Site Location and Access ‘proposed development’) consisting of up to seven wind turbines with a total installed generating capacity of up to 24.5 megawatts (MW), located The proposed development site is located on land at Todrig Farm and within the local authority area administered by Scottish Borders Council Whitslade Farm, 7km south west of Ashkirk, 3.5km north west of (SBC). The site centre is approximately at Ordnance Survey (OS) Roberton and 9km west of Hawick, in the Scottish Borders. National Grid coordinates NT412178. The proposed development site comprises moorland and rough grazing, As the proposed development is considered a project likely to give rise to currently used for sheep grazing and managed for seasonal game ‘significant environmental effects’, and in accordance with the shooting. The Hyndhope and Alemoor Forest, a large commercial forest requirements of the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact plantation predominantly comprising of Sitka Spruce, lies to the west of Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (the ‘EIA Regulations’), an the site, through which access from the B711 will be taken using the Environmental Statement (ES) has been prepared to accompany the existing access track to the operational Langhope Rig Wind Farm, application for planning permission for the development. located approximately 2km to the north of the proposed development. This Non-technical Summary (NTS) provides an overview of the key No residential properties are located within the proposed development findings of the ES. -

Newsletter - January 2020

WalkingSupport - Newsletter - January 2020 Best Wishes for the New Year This is the time of year when many walkers start to look to the spring and summer to consider how they might get out and enjoy the countryside after what has been a wet and somewhat dismal winter. We hope that as the days start to lengthen the opportunity to get out and enjoy some of the many walking routes will become a reality. Walking Support extends our best wishes for 2020 to all our past, present and future clients. Special Offer 15% Reduction on our planning and booking fees for 2020 walks if your requirement is confirmed prior to the end of February 2020. Walking Support is a one stop planning and booking business for self led walks on the following long distance routes: Great Glen Way Rob Roy Way Cateran Trail West Highland Way Fife Coastal Path Forth Clyde and Union Canals Southern Upland Way – Sir Walter Scott Way Borders Abbeys Way St Cuthbert’s Way St Oswald’s Way Northumberland Coastal Path Hadrian’s Wall Path – Roman Heritage Way Weardale Way Deeside Way For fuller details simply link to our website home page www.walkingsupport.co.uk. Walking Support will provide you with an outline plan and cost estimate before there is any commitment to use our services. All packages are tailor made to the clients requirements, we do not offer standard off the shelf walking holidays*. To visit comprehensive websites on almost all of the above walking routes simply click on www.walkingsupport.co.uk/routes.html and highlight the one that is of immediate interest. -

Human Environment Baseline.Pdf

Moray Offshore Renewables Limited - Environmental Statement Telford, Stevenson and MacColl Offshore Wind Farms and Transmission Infrastructure 5 Human Environment 5.1 Commercial Fisheries 5.1 5.1.1 Introduction 5.1.1.1 This chapter summarises the baseline study of commercial fishing activities, including salmon and sea trout fisheries, in the vicinity of the three proposed development sites (Telford, Stevenson and MacColl) and the offshore transmission infrastructure (OfTI). For the purpose of this study, commercial fishing is defined as CHAPTER any legal fishing activity undertaken for declared taxable profit. 5.1.1.2 The following technical appendices support this chapter and can be found as: Technical Appendix 4.3 B (Salmon and Sea Trout Ecology Technical Report). Technical Appendix 5.1 A (Commercial Fisheries Technical Report). 5.1.1.3 For the purposes of this assessment, salmon and sea trout fisheries in the Moray Firth are separately addressed to other commercial fisheries, as a result of their being located largely in-river (with the exception of some coastal netting) and being different in nature to the majority of marine commercial fishing activities. In addition, due to the migratory behaviour of salmon and sea trout, fisheries have been assessed for all rivers flowing into the Moray Firth. It is also recognised that salmon is a qualifying feature or primary reason for Special Area of Conservation (SAC) site selection of the following rivers in the Moray Firth: Berriedale and Langwell Waters SAC (primary reason); River Moriston -

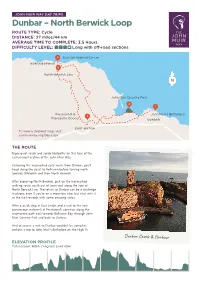

North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 Miles/44 Km AVERAGE TIME to COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with Off-Road Sections

JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar – North Berwick Loop ROUTE TYPE: Cycle DISTANCE: 27 miles/44 km AVERAGE TIME TO COMPLETE: 3.5 Hours DIFFICULTY LEVEL: Long with off-road sections 4 Scottish Seabird Centre NORTH BERWICK 5 North Berwick Law John Muir Country Park 2 1 Prestonmill & John Muir’s Birthplace 3 Phantassie Doocot DUNBAR EAST LINTON To view a detailed map, visit joinmuirway.org/day-trips THE ROUTE Enjoy quiet roads and sandy footpaths on this tour of the easternmost section of the John Muir Way. Following the waymarked cycle route from Dunbar, you’ll head along the coast to Belhaven before turning north towards Whitekirk and then North Berwick. After exploring North Berwick, pick up the waymarked walking route south out of town and along the foot of North Berwick Law. The return to Dunbar can be a challenge in places, even if you’re on a mountain bike, but stick with it as the trail rewards with some amazing vistas. After a quick stop in East Linton and a visit to the very picturesque watermill at Prestonmill, continue along the waymarked path east towards Belhaven Bay, through John Muir Country Park and back to Dunbar. And of course a visit to Dunbar wouldn’t be complete without a trip to John Muir’s Birthplace on the High St. Dunbar Castle & Harbour ELEVATION PROFILE Total ascent 369m / Highest point 69m JOHN MUIR WAY DAY TRIPS Dunbar - North Berwick Loop PLACES OF INTEREST 1 JOHN MUIR’S BIRTHPLACE Pioneering conservationist, writer, explorer, botanist, geologist and inventor. Discover the many sides to John Muir in this museum located in the house where he grew up. -

ARGYLL and BUTE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT SERVICES 16 December 2008

ARGYLL AND BUTE COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT SERVICES 16 December 2008 THE COWAL WAY – REQUEST FOR SUPPORT FROM ARGYLL & BUTE COUNCIL 1. SUMMARY 1.1 Colintraive & Glendaruel Community Council are requesting that the Council recognises the importance of the Cowal Way which links Portavardie with Inveruglas on Loch Lomond to the economy of the Cowal Peninsula. See Maps in Appendix 1. 1.2 The Community Council is also seeking funding to ensure the future of the route. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 That the Committee recognises the value of the Cowal Way to the people and economy of the Cowal Peninsula and the need to protect and promote this asset. 2.2 Welcomes the inclusion of the entire length of the Cowal Way in the proposed Core Paths Network, and supports this during the forthcoming public consultation. 2.3 Supports the establishment of a group or body to manage the Cowal Way drawing representation from all 5 Community Council Areas through which it passes, Council Officers, Elected Members, and Agencies including SNH, FCS and AIE. 2.4 Provides the Cowal Way with £10,000 from the Access Budget to allow the Colintraive and Glendaruel Community Council to begin raising the £48,000 required to make urgent repairs to the path. The Access Team will also support the Community Council in making bids to potential funders including the Scottish Rural Development Programme. 2.5 Support the proposal by the Access Team to install a suitable counter on the Cowal Way to establish the level of current use to justify continued investment in the route.