GUEST LAW by John C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamoure County Cbicenteiyyal Celebtalion

LaMoure County cBicenteiyyal Celebtalion JULY 2, 3, 4, 5, 1976 MEMORIAL PARK — GRAND RAPIDS, N.D. •-:i DEDICATION To the men, women and youth who founded, united, de fended and built this country and our communities this celebra tion and publication are dedicated. PREFACE The LaMoure County Bicentennial Celebration being held at Grand Rapids Park is a rather unique event in several ways. First it is noteworthy because it is a countywide cele bration calling for the good will and cooperation of people from all parts of the County and some of the nearby towns and cities. Getting this many people and communities to work together even on a common patriotic program, is a noteworthy achieve ment. It is also significant because it presents a variety of his toric and patriotic events at a time when it has become popular to downgrade our past and belittle the efforts and sacrifices that have been made on our behalf. We have a glorious past and a rich heritage and we are glad to have the opportunity to present some of it. It was thought that something should be placed in writing about LaMoure County in 1976 and of some of the events that have led up to this Bicentennial year. This booklet is not in tended to be a history of LaMoure County or its communities. Nor is it a narrative of the families of LaMoure County, inter esting though they may be. Many excellent historical books have been written about various communities and families of LaMoure County and we do not wish to duplicate those fine works. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Cooked in the Lab Dark, Techy D&B Trio Ivy Lab Break Bad on LP P.108

MUSIC DECEMBER ON THE DANCEFLOOR This month’s tracks played out p. 92 GO LONG! The long-players listened to p. 108 WILD COMBINATION The most crucial compilations p. 113 Cooked In The Lab Dark, techy d&b trio Ivy Lab break bad on LP p.108 djmag.com 091 HOUSE REVIEWS BEN ARNOLD [email protected] melancholy pianos, ‘A Fading Glance’ is a lovely, swelling thing, QUICKIES gorgeously understated. ‘Mayflies’ is brimming with moody, building La Fleur Fred P atmospherics, minor chord pads Make A Move Modern Architect and Burial-esque snatches of vo- Watergate Energy Of Sound cal. ‘Whenever I Try To Leave’ winds 9.0 8.5 it up, a wash of echoing percus- The first lady of Berlin’s A most generous six sion, deep, unctuous vibrations Watergate unleashes tracks from the superb and gently soothing pianos chords. three tracks of Fred Peterkin. It’s all This could lead Sawyer somewhere unrivalled firmness. If great, but ‘Tokyo To special. ‘Make A Move’’s hoover Chiba’, ‘Don’t Be Afraid’, bass doesn’t get you, with Minako on vocals, Hexxy/Andy Butler ‘Result’’s emotive vibes and ‘Memory P’ stand Edging/Bewm Chawqk will. Lovely. out. Get involved. Mr. Intl 7. 5 Various Shift Work A statuesque release from Andy Hudd Traxx Now & Document II ‘Hercules & Love Affair’ Butler’s Mr. Then Houndstooth Intl label. Hexxy is his new project Hudd Traxx 7. 5 with DJ Nark, founder of the excel- 7. 5 Fine work in the lent ‘aural gallery’ site Bottom Part four of four in this hinterland between Forty and Nark magazine. -

I.Logging Accident Claims Loyd Harris

,. ~' .. _. '."', " ,.'-..... , -. -- ..-·l.<o,"".·"···" ,. .'" .. ", . "" . '. " • • , . • • • ,. • . • « i ... • • ., " '. •I • .. " ..,~ft1 tf.. ·$.·aIghwa, 10, ~e ~u.rt "...AU ~"gh til., Sc,nlc; So~hw8$t, to Reapb Ruic:toso, Wodd'll • . '. " ". Lal'gQsf' Y8al',,'Botmd MollDtain .PJaygrollnu " ',' . CONSUJ.,T Yotm. "0·11;; PAINTINGS , . ~ . , O~ .' INSURANCE AGENT, . mE.W.i!:S'.t , ~ YOU would your la~er. doctor . , . HARRIS SHELTON The or.I.banker. S~er StucUQ • WARREN BARRETT•. I'bJlil~t )I~co N.ew INSU1l0R~ • . .Wmter Studio . • ~• 1411 JUcllmolld at. EI l'~ T~ . Phone 3345 . " PriJued~d Published In the PJavgrollnq of *be Southwest ----------~-------- v.;,.,;.;,O.;..L:.:;UMl':.:,....,;....,.;...l'i..;..• ..;..~..:.'..:....:..~..:.'ED..,...;.. ..:..~_._........,._'--=:'_._...,.......,+....__........,...............,~.;,.. .....-..2a~UI~D~O~:5~O:..• .!:LJ~H~C~O~LH~.~c:O~U~"~T~Y~.!m:~.~W~.NE~~X~I~Cf:0~__...:..."t"""'.....,-.....,..._.. ~F.~Il~I~D~J'r.;!Y:..., ;J.::!l,J!::I.!.Y";8~,..!1~S~S6~......,.,_ ........_.::::o::::"......,......,........,__........,_...:I.::H.:VE=HI~EpM:.U=S::...;V;.:I:.:AM:::..· .:.:A;.:U;.:T..;F:.;A;:C.:::;I::E::M~U::S:."===S~U=B:S=C~1Jl=P='1'=I::::O=H=$2:,S:o:.~=r:Y:.:u ..__........~.-._ ...... _-.., ...... ~_ .., , AROUND I.~. I. LOGGING ACCIDENT , , TOWN ..',,,- , . CLAIMS LOYD HARRIS The· hazardous oc~upntlon of County. Texas, April 15, 1915. lind ., logging claimed another llte this was a veternn of World War II. week !lore. The second victim this having lIervedln t~e All' Force in • year was also a Green Tl'ee mlin. the 52nd Squadron. He was 1I r;or~ l Loyd C. RarrlB, who was cn\shed pornl at the time ot his disc~arge. -

COF5-59V13 N1.Qxd 12/12/2002 3:57 PM Page 5

COF5-59v13 n1.qxd 12/12/2002 3:57 PM Page 5 Order PREVIEWS Form V1V13#1 ORDER DEADLINE: JANUARY 11, 2002 PLACE STORE STAMP HERE Name _______________________________ Address _____________________________ City _________________State ___________ Zip ___________ Phone# _______________ Signature (Required) __________________ Your signature indicates that you are authorized to order items that are designated as “Adult,” and you are at least 18 years old. PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY! QTY TITLE PRICE Please note that the toy items on this order form may not be available at every store. Shipping times and prices may vary. For items sold by assortment (marked with an "*"), retailers cannot guarantee receiving specific items. Ask your retailer for more information when you order. PAGE 2 DIAMOND PUBLICATIONS SPOT ______JAN03 0001 MEGA MANGA AND MORE CATALOG 2002 ............................................................MSRP: $0.95 = $ ____________ ____________JAN03 0003 PRIMO FLYER VOL XIII #3 ..................................................................................................SRP: PI = $ ____________ ____________JAN03 0004 PREVIEWS VOL XIII #3 ............................................................................................MSRP: $3.95 = $ ____________ ____________JAN03 0005 PREVIEWS VOL XIII CONSUMER ORDER FORM #3 ............................................................SRP: PI = $ ____________ ____________JAN03 0007 PREVIEWS ADULT VOL XIII #3 ..................................................................................MSRP: -

Alderac Entertainment Grouppresents Ultimate Toolbox

ALDERAC ENTERTAINMENT GROUP PRESENTS ULTIMATE TOOLBOX WRITING AND DEVELOPMENT DAWN IBACH JEFF IBACH JIM PINTO ADDITIONAL WRITING DALE C. MCCOY, JR. EDITING JANICE M. SELLERS COVER ART MATTHEW ARMSTRONG GRAPHIC DESIGN DAVE AGOSTON JIM PINTO INTERIOR ART JONATHAN HUNT CARTOGRAPHY ED BOURELLE CREATIVE MANAGER JIM PINTO PRODUCTION MANAGER DAVE LEPORE SPECIAL THANKS BRUCE ALDERMAN JANEL BISACQUINO JON HODGSON AMANDA JOSE SARAO ANGELO SARGENTINI DEDICATION FOR ERIC WUJCIK, WHO INSPIRED US ALL Copyright © 2009 Alderac Entertainment Group. All rights reserved. Printed in Canada FREE PDF Chapter ENWORLD/PAIZO FREE 2 FREE PDF Castle Names 1 Aberdun, Castle of the Neverborn 2 Achaddler, Fortress of Knighthood 3 Aggstein, House of the Lordstaff 4 Arkenvoch, Guardian of the waves 5 Boneshaw, Hold of the Crypthalls of Deneth 6 Boredun, Stones of the Withered Sage 7 Braemar, Keep of the Moonmark 8 Buckley, Eternal guardian of the Monarchy 9 Cordatch, Blight of the Gnoll Lords 10 Cragsthorn, Hold of the rulers of Demonblood 11 Dundeer, Fortress of Suntold Truth 12 Essemont, Stronghold of Destiny 13 Huntmane, Ranger-Lodge of Evermure 14 Kinndun, House of the Forseen Queen 15 Kolmitz, Manor of the Obsidian Scouts 16 Lochwood, Keep of the Swamplight 17 Ravenscrag, Haunted ruin of the Delverealm 18 Tagdun, Bastion of the orcs of Puketongue 19 Weilsneg, Cradle of the Princess Valtume 20 Wittingham, walls of the Crown of Faitholme Castle Fate 1 Abandoned under unknown, but extremely shameful circumstances 2 Contrary rumors speak in a hundred directions, -

S Album of the Week: the Slackers

Rob’s Album Of The Week: The Slackers Ska is a genre that has been in a bit of a crossroads over the past few years. It’s kind of in the same position punk rock was in the late 2000s, out of the limelight but still around somewhat, and there’s a dedicated fan base still packing venues to dance to the rhythms. For 25 years The Slackers from New York City have been keeping two tone alive and they’re not going away. Furthering the latter is their brand new self-titled album coming out on February 19. Bringing that trademark jazzy spin on the genre, Vic Ruggiero and crew haven’t slowed down at all since coming up from Manhattan in 1991. The groovy sextet from The Big Apple incorporates a bit of psychedelia and garage rock in their latest release. Each track brings something different; a few are heavy with the horns while others have the keys as the base of the entire song. It definitely makes the experience a stimulating one. It’ll be difficult to grow bored while diving to this one. Ruggiero also brings that laid back soul he’s known for to keep everything timeless. Is Ska due for the 4th Wave? Only time will tell. It’ll take a bunch of kids rejuvenating the rude boy ideal and that’s only a small part of what it’ll take. A big part of this weekly review are my top tracks off of the Album Of The Week. Open wide, take a bite, repeat and get your fill. -

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last Updated: September 15, 2020

Graphic Novel Finding Aid for Merril Collection of Science Fiction, Speculation & Fantasy Last updated: September 15, 2020 Most books in this list are in English. We have some graphic novels in other languages . Books are listed alphabetically by series title. Books in series are listed in numerical order (if possible) — otherwise they’re listed alphabetically by sub-title. A | B |C |D | E |F |G | H | I| J| K | L | M | N |O | P | Q| R |S | T| U | V | W | X | Y | Z Title Writer/Artist Notes A A.B.C. Warriors. The Mills, Pat and Kevin A.B.C. Warriors began in Mek-nificent Seven O’Neill and Mike Starlord. McMahon A. D.: after death Snyder, Scott and Jeff Lemire A.D.D. : Adolescent Rushkoff, Douglas Demo Division et al. Aama. 1, The smell Peeters, Frederick of warm dust Aama. 2, The Peeters, Frederick invisible throng Aama. 3, The desert Peeters, Frederick of mirrors The Abaddon Shadmi, Koren Abbott Ahmed, Saladin and Originally published in single others magazine form as Abbott, #1-5. Aama. 4, You will be Peeters, Frederick glorious, my daughter Abe Sapien. Vol. 1, Mignola, Mike et al. The drowning Abe Sapien. Vol. 2, Mignola, Mike et al. The devil does not jest and other stories Across the Universe. Moore, Alan et al. “Superman annual” #11; The DC Universe “Detective comics” #549, 550, stories of Alan “Green Lantern” #188; Moore “Vigilante” #17, 18; “The Omega men” #26, 27; “DC Comics presents” #85; “Tales of the Green Lantern corps annual” #2, 3; “Secret origins” #10; “Batman annual” #11 The Action heroes Gill, Joe et al. -

06/12/2020 This Catalogue Cancels And

www.endofsilence.net This catalogue cancels and replaces any previous catalogue 06/12/2020 Questo catalogo annulla e sostituisce i cataloghi in data precedente LP (New, Used & Rarities) CD 1917 (Argentina) - Vision - CD, Album, RE, VG/VG+ € 4,90 217 - Atheist Agnostic Rationalist - CD, Album, Sealed M/M € 7,90 3 Inches Of Blood - Advance And Vanquish - CD, Album, Great copy, like new! NM/NM € 7,90 36 Crazyfists - Bitterness The Star - CD, Album, Sealed M/M € 6,90 95-C - Stuck In The past - CD, NM/VG+ € 4,90 A.N.I.M.A.L. - Animal 6 - CD, Album, Like new NM/NM € 7,90 Abominant - Onward To Annihilation - CD, Album, Dig, Sealed M/M € 9,90 ABORYM - Generator - CD - € 9,90 ABORYM - WITH NO HUMAN INTERVENTION - CD - 2003 - G /VG - USED € 5,90 Aborym - Psychogrotesque - CD, Album, Ltd, Dig, M/M € 9,90 Abrasive - Awakening of lust - CD € 6,90 Absolute Defiance - Systematic terror decimation - CD € 4,90 ABYSSUS - Into the Abyss - CD - € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - CD € 9,90 AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - CD € 11,90 AC/DC - Let Ther Be Rock - CD € 7,90 AC/DC - Rock or Bust - CD Digi Sealed € 11,90 AC/DC - Stiff upper lip - CD € 7,90 ACCEPT - DEATH ROW - CD - US PRESS 1995 - VG/VG - Used € 9,90 Accept - Hungry years - CD. Used € 6,90 ACCEPT - Metal heart - CD - Remastered Sealed € 9,90 Acheron - Kult Des Hasses - CD, Album, Sli, Sealed M/M € 7,90 ACROSTICHON - Engraved in Black - CD - Memento Mori Rec € 9,90 Action Swingers - More Fast Numbers - CD, EP, NM/VG+ € 4,90 www.endofsilence.net WhatsApp/Telegram/SMS: +39 3518979595 www.endofsilence.net [email protected] Pag. -

The Unpredictable Path of Faith No More's Mike Patton

CULT KINGThe unpredictable path of Faith No More’s Mike Patton TEXT BY SCOTT MORROW · PHOTOS BY NICK AITKEN · PHOTO ASSISTANCE BY LEANNE COWAN 56 ISSUE 41 ALARM MAGAZINE ISSUE 41 ALARM MAGAZINE 57 TK “Sometimes it’s just not worth harboring any bullshit and [instead] trying to move on. And musicians move on by making music together.” ome musicians achieve broad suc- Mr. Bungle, John Zorn’s Moonchild). They’ve Listeners, in fact, might be surprised to learn cess, some attain cult status, and been guests on dozens of other albums, from that Patton—who seldom is seen on stage with some defy all explanation. And Björk to Sepultura, and they retain one of the more than a microphone, a sampler or keyboard, then there’s Mike Patton, who widest ranges in modern music. and effects pedals—is a reclusive multi-instru- somehow has done all three. mentalist. In the privacy of his home studio and S During that time, however, one important with a war chest of sounds, he played nearly Even if you don’t know the Faith No More part of Patton’s résumé—being a full-blown every instrument on his genre-hopping theme- front-man’s immense, indescribable catalog, cinema songsmith—has gotten buried behind and-variation scores for A Perfect Place and chances are that you’ve heard his voice— his status as vocalist extraordinaire. Crank: High Voltage. And even though Patton whether from FNM’s mega-hit “Epic” in the records many parts note by note to cut, arrange, late 1980s or from his voiceover work in the In actuality, the iconoclast always has been a and layer, the results are startling—particularly movie I Am Legend or in video games such as skilled songwriter and arranger; much of Faith on records with minimal vocals, complex musi- Left 4 Dead and The Darkness. -

Titles in Comicbase 9 2002 Tokyopop Manga Sampler 2010

Titles in ComicBase 9 2002 Tokyopop Manga Sampler 2010 2020 Visions Titles in blue are new to this edition. 2024 Please see the title notes at the bottom 2099 A.D. of this document for a list of titles that 2099 A.D. Apocalypse have been changed since the previous 2099 A.D. Genesis version. 2099: Manifest Destiny 2099 Special: The World of Doom 100% 2099 Unlimited 1,001 Nights of Bacchus, The 2099: World of Tomorrow 1001 Nights of Sheherazade, The 20 Nude Dancers 20 Year One Poster 100 Bullets Book 100 Degrees in the Shade 20 Nude Dancers 20 Year Two 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time, The 20th Century Eightball 100% Guaranteed How-To Manual 21 for Getting Anyone to Read Comic 2112 (John Byrne’s…) Books!!! (Christa Shermot’s…) 21 Down 100 Pages of Comics 22 Brides 100% True? 24 101 Other Uses For a Condom 2 Fun Flip Book 101 Ways to End the Clone Saga 2-Headed Giant 10th Muse 2 Hot Girls on a Hot Summer Night 10th Muse (Vol. 2) 2 Live Crew Comics 10th Muse/Demonslayer 2 To the Chest 10th Muse Gallery 300 1111 303 13: Assassin Comics Module 30 Days of Night 13 Days of Christmas, The: A Tale of 30 Days of Night: Return to Barrow the Lost Lunar Bestiary 32 Pages 13th of Never, The .357! 1963 39 Screams, The 1984 Magazine 3-D Adventure Comics 1994 Magazine 3-D Alien Terror 1st Folio 3-D Batman 2000 A.D. 3-D-ell 2000 A.D. Extreme Edition 3-D Exotic Beauties 2000 A.D. -

Order Form Full

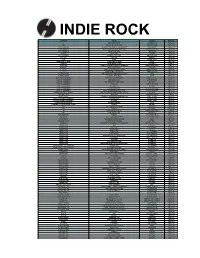

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I.