Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvador Dalí. De La Inmortal Obra De Cervantes

12 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE LA COLECCIÓN Salvador Dalí, Don Quijote, 2003. Salvador Dalí, Autobiografía de Ce- llini, 2004. Salvador Dalí, Los ensa- yos de Montaigne, 2005. Francis- co de Goya, Tauromaquia, 2006. Francisco de Goya, Caprichos, 2006. Eduardo Chillida, San Juan de la Cruz, 2007. Pablo Picasso, La Celestina, 2007. Rembrandt, La Biblia, 2008. Eduardo Chillida, So- bre lo que no sé, 2009. Francisco de Goya, Desastres de la guerra, 2009. Vincent van Gogh, Mon cher Théo, 2009. Antonio Saura, El Criti- cón, 2011. Salvador Dalí, Los can- tos de Maldoror, 2011. Miquel Bar- celó, Cahier de félins, 2012. Joan Miró, Homenaje a Gaudí, 2013. Joaquín Sorolla, El mar de Sorolla, 2014. Jaume Plensa, 58, 2015. Artika, 12 years of excellence Índice Artika, 12 years of excellence Index Una edición de: 1/ Salvador Dalí – Don Quijote (2003) An Artika edition: 1/ Salvador Dalí - Don Quijote (2003) Artika 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 2/ Salvador Dalí - Autobiografía de Cellini (2004) Avenida Diagonal, 662-664 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, Spain 3/ Salvador Dalí - Los ensayos de Montaigne (2005) 08034 Barcelona, España 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 4/ Francisco de Goya - Tauromaquia (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 5/ Francisco de Goya - Caprichos (2006) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 6/ Eduardo Chillida - San Juan de la Cruz (2007) 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Summary 7/ Pablo Picasso - La Celestina (2007) Sumario 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) A walk through twelve years in excellence in exclusive art book 8/ Rembrandt - La Biblia (2008) Un recorrido por doce años de excelencia en la edición de 9/ Eduardo Chillida - Sobre lo que no sé (2009) publishing, with unique and limited editions. -

Calder and Sound

Gryphon Rue Rower-Upjohn Calderand Sound Herbert Matter, Alexander Calder, Tentacles (cf. Works section, fig. 50), 1947 “Noise is another whole dimension.” Alexander Calder 1 A mobile carves its habitat. Alternately seductive, stealthy, ostentatious, it dilates and retracts, eternally redefining space. A noise-mobile produces harmonic wakes – metallic collisions punctuating visual rhythms. 2 For Alexander Calder, silence is not merely the absence of sound – silence gen- erates anticipation, a bedrock feature of musical experience. The cessation of sound suggests the outline of a melody. 3 A new narrative of Calder’s relationship to sound is essential to a rigorous portrayal and a greater comprehension of his genius. In the scope of Calder’s immense œuvre (thousands of sculptures, more than 22,000 documented works in all media), I have identified nearly four dozen intentionally sound-producing mobiles. 4 Calder’s first employment of sound can be traced to the late 1920s with Cirque Calder (1926–31), an event rife with extemporised noises, bells, harmonicas and cymbals. 5 His incorporation of gongs into his sculpture followed, beginning in the early 1930s and continuing through the mid-1970s. Nowadays preservation and monetary value mandate that exhibitions of Calder’s work be in static, controlled environments. Without a histor- ical imagination, it is easy to disregard the sound component as a mere appendage to the striking visual mien of mobiles. As an additional obstacle, our contemporary consciousness is clogged with bric-a-brac associations, such as wind chimes and baby crib bibelots. As if sequestered from this trail of mainstream bastardi- sations, the element of sound in certain works remains ulterior. -

August Highlights at the Grant Park Music Festival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jill Hurwitz,312.744.9179 [email protected] AUGUST HIGHLIGHTS AT THE GRANT PARK MUSIC FESTIVAL A world premiere by Aaron Jay Kernis, an evening of mariachi, a night of Spanish guitar and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on closing weekend of the 2017 season CHICAGO (July 19, 2017) — Summer in Chicago wraps up in August with the final weeks of the 83rd season of the Grant Park Music Festival, led by Artistic Director and Principal Conductor Carlos Kalmar with Chorus Director Christopher Bell and the award-winning Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion in Millennium Park. Highlights of the season include Legacy, a world premiere commission by the Pulitzer Prize- winning American composer, Aaron Jay Kernis on August 11 and 12, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 with the Grant Park Orchestra and Chorus and acclaimed guest soloists on closing weekend, August 18 and 19. All concerts take place on Wednesday and Friday evenings at 6:30 p.m., and Saturday evenings at 7:30 p.m. (Concerts on August 4 and 5 move indoors to the Harris Theater during Lollapolooza). The August program schedule is below and available at www.gpmf.org. Patrons can order One Night Membership Passes for reserved seats, starting at $25, by calling 312.742.7647 or going online at gpmf.org and selecting their own seat down front in the member section of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. Membership support helps to keep the Grant Park Music Festival free for all. For every Festival concert, there are seats that are free and open to the public in Millennium Park’s Seating Bowl and on the Great Lawn, available on a first-come, first-served basis. -

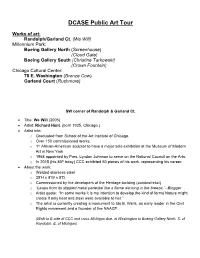

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015

The Economic Impact of Parks and Recreation Chicago, Illinois July 30 - 31, 2015 www.nrpa.org/Innovation-Labs Welcome and Introductions Mike Kelly Superintendent and CEO Chicago Park District Kevin O’Hara NRPA Vice President of Urban and Government Affairs www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Economic Impact of Parks The Chicago Story Antonio Benecchi Principal, Civic Consulting Alliance Chad Coffman President, Global Economics Group www.nrpa.org/Innovation-labs Impact of the Chicago Park District on Chicago’s Economy NRPA Innovation Lab 30 July 2015 The charge: is there a way to measure the impact of the Park Districts assets? . One of the largest municipal park managers in the country . Financed through taxes and proceeds from licenses, rents etc. Controls over 600 assets, including Parks, beaches, harbors . 11 museums are located on CPD properties . The largest events in the City are hosted by CPD parks 5 Approach summary Relative improvement on Revenues generated by value of properties in parks' events and special assets proximity . Hotel stays, event attendance, . Best indicator of value museum visits, etc. by regarding benefits tourists capture additional associated with Parks' benefit . Proxy for other qualitative . Direct spending by locals factors such as quality of life indicates economic . Higher value of properties in significance driven by the parks' proximity can be parks considered net present . Revenues generated are value of benefit estimated on a yearly basis Property values: tangible benefit for Chicago residents Hypothesis: . Positive benefit of parks should be reflected by value of properties in their proximity . It incorporates other non- tangible aspects like quality of life, etc. -

Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) the Ghost (Maquette), 1964 Painted Sheet Metal, Metal Rods, and Steel Wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.13

PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) The Ghost (maquette), 1964 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.13 Alexander Calder redefined sculpture in the 1940s by incorporating the element of movement. He created motorized works and later hanging sculptures, or “mobiles,” that rotate freely in response to airflow. Using wire, found objects, and industrial materials, Calder constructed three-dimensional line drawings of people, animals, and objects that he activated with kinetic verve. PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Performing Seal, 1950 Painted sheet metal and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.7 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Orange Paddle Under the Table, c. 1949 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.11 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Chat-mobile (Cat Mobile), 1966 Painted sheet metal and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.10 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Snowflakes and Red Stop, 1964 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.14 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Little Face, 1943 Copper wire, thread, glass, and wood Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.6 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Bird, 1952 Coffee cans, tin, and copper wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.8 PB Takis (Greek, b. 1925) Magnetic Mobile, c. 1964 Glass, plastic, wood, and electric cord Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Mrs. Robert B. Mayer, 1982.32 Since the 1950s, Greek artist and inventor Panayiotis “Takis” Vassilakis has investigated the relationship between art and science. -

Grant Park Master Plan

CHAPTER 4 Waterfronts and Open Spaces Grant Park Master Plan The major goals of the Grant Park Plan include: • Expand the role of Grant Park as a regional, city-wide and local resource • Activate the park as a whole, on a year-round basis, especially on non-event days and during the winter • Protect and enhance the unique landscape of the park • Preserve and interpret the park’s historic character while accommodating its evolving uses, including the needs of new residential developments on its periphery • Integrate Grant Park into the Lakefront open Figure 4.3.10 Queen’s Landing space system • Develop short and long-range guidelines for land-use, management, maintenance, transportation, roadway design and park development • Integrate the planning process for Grant Park with the plans for other facilities of the Central Lakefront • Develop Butler Field as sports fields • Introduce a performance venue at Hutchinson Field • Extend pathways over the railroad rights of way Figure 4.3.9 The Grant Park Master Plan Figure 4.3.11 Neighborhood Park Area Final Report June 2003 DRAFT 84 CHAPTER 4 Waterfronts and Open Spaces Millennium Park First conceived in 1997, Millennium Park will become one of the finest recreational and cultural spaces of any city in the world. The new park has added 16 acres to Grant Park by construct- ing a land bridge over the Metra Railroad tracks. The design, financed through public-private partnership, includes an outdoor ice rink, an award-winning band shell designed by architect Frank Gehry, a 1500-seat Music and Dance Theater, and extensive public sculptures, gar- dens, green spaces and promenades. -

Calder / Dubuffet Entre Ciel Et Terre Entre Ciel Et Terre © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /Preface Foreword

CALDER / DUBUFFET ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /PREFACE FOREWORD/ Opera Gallery Genève est heureuse de présenter une exposition exceptionnelle regroupant des œuvres de deux Opera Gallery Geneva is pleased to present an exceptional exhibition with works by two giants of the 20th century: géants du 20ème siècle : Alexander Calder et Jean Dubuffet. Au premier regard, leurs parcours et œuvres sont bien Alexander Calder and Jean Dubuffet. At first glance, their careers and work are very different, but a lot of elements différents, pourtant beaucoup d’éléments les rapprochent. draw them together. Ces deux artistes sont de la même génération mais ne se sont jamais rencontrés. Alexander Calder était These two artists are from the same generation but never met. Alexander Calder was American and Jean Dubuffet américain et Jean Dubuffet français. les deux ont vécu leurs vies artistiques des deux côtés de l’Atlantique. was French. Both have lived their artists’ lives travelling from one continent to the other. Both have been, at les deux ont été, au début de leurs carrières respectives, considérés comme des “outsiders” dans leurs propres the beginning of their respective careers considered as “outsiders” in their own country but their talent was pays mais leur talent a été immédiatement reconnu en France pour Calder et aux etats-Unis pour Dubuffet. immediately acknowledged in France for Calder and in America for Dubuffet. tous deux ont “révolutionné” l’art dit conventionnel grâce à une utilisation audacieuse de techniques et matériaux Both have revolutionized conventional art by an audacious use of informal techniques and materials. -

Art and Economics in the City

Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City Urban Studies Caterina Benincasa, art historian, is founder of Polyhedra (a nonprofit organi- zation focused on the relationship between art and science) and of the Innovate Heritage project aimed at a wide exchange of ideas and experience among scho- lars, artists and pratictioners. She lives in Berlin. Gianfranco Neri, architect, teaches Architectural and Urban Composition at Reggio Calabria “Mediterranea” University, where he directs the Department of Art and Territory. He extensively publishes books and articles on issues related to architectural projects. In 2005 he has been awarded the first prize in the international competition for a nursery in Rome. Michele Trimarchi (PhD), economist, teaches Public Economics (Catanzaro) and Cultural Economics (Bologna). He coordinates the Lateral Thinking Lab (IED Rome), is member of the editoral board of Creative Industries Journal and of the international council of the Creative Industries Federation. Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City New Cultural Maps An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-4214-2. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.know- ledgeunlatched.org. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. -

Bay Area Economics Draft Report – Study Of

DRAFT REPORT Study of Alternatives to Housing For the Funding of Brooklyn Bridge Park Operations Presented by: BAE Urban Economics Presented to: Brooklyn Bridge Park Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) February 22, 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i Introduction and Approach ........................................................................................... 1 Committee on Alternatives to Housing (CAH) Process ............................................................ 1 Report Purpose and Organization ............................................................................................. 2 Topics Outside the Scope of the CAH and this Report ............................................................. 3 Report Methodology ................................................................................................................. 4 Limiting Conditions .................................................................................................................. 4 Park Overview and the Current Plan ............................................................................ 5 The Park Setting and Plan ......................................................................................................... 5 Park Governance ....................................................................................................................... 6 The Current Financing Plan ..................................................................................................... -

Masters Thesis

WHERE IS THE PUBLIC IN PUBLIC ART? A CASE STUDY OF MILLENNIUM PARK A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corrinn Conard, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. James Sanders III, Advisor Advisor Professor Malcolm Cochran Graduate Program in Art Education ABSTRACT For centuries, public art has been a popular tool used to celebrate heroes, commemorate historical events, decorate public spaces, inspire citizens, and attract tourists. Public art has been created by the most renowned artists and commissioned by powerful political leaders. But, where is the public in public art? What is the role of that group believed to be the primary client of such public endeavors? How much power does the public have? Should they have? Do they want? In this thesis, I address these and other related questions through a case study of Millennium Park in Chicago. In contrast to other studies on this topic, this thesis focuses on the perspectives and opinions of the public; a group which I have found to be scarcely represented in the literature about public participation in public art. To reveal public opinion, I have conducted a total of 165 surveys at Millennium Park with both Chicago residents and tourists. I have also collected the voices of Chicagoans as I found them in Chicago’s major media source, The Chicago Tribune . The collection of data from my research reveal a glimpse of the Chicago public’s opinion on public art, its value to them, and their rights and roles in the creation of such endeavors.