Calder and Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TGE) & the JOB Board

1 2017 The Grape Exchange (TGE) & The JOB Board As of 7/1/17, Christy Ecktein will be handling OGEN, TGE & TJB. Please contact Christy at [email protected] This service is provided by the OSU viticulture program. The purpose of this site is to assist grape growers and wineries in selling and/or buying grapes, wine, juice or equipment and post JOBS Wanted or JOBS for Hire. The listing will be posted to the “Buckeye Appellation” website (https://ohiograpeweb.cfaes.ohio-state.edu/ ) and updates will be sent to all OGEN subscribers via email. Ads will be deleted after 4 months. If you would like items to continue or placed back on the exchange, please let me know. To post new or make changes to current ads, please send an e-mail to Christy Eckstein ([email protected]) with the contact and item description information below. Weekly updates of listings will be e-mailed to OGEN subscribers or as needed throughout the season. Suggestions to improve the Grape Exchange are also welcome. The format of the information to include is as follows: Items (grapes, wine, equipment, etc) Wanted/Needed or Selling: Name: Vineyard/Winery: Phone Number: E-mail Address: Note: Please send me a note to delete any Ads that you no longer need or want listed. There are currently four jobs listed on The JOB Board. Updates to TGE are listed as most current to oldest. *Please scroll down to Ads, pictures & contact information 2 The Grape Exchange September 21, 2017 (32) For Sale: Niagra and Concord grapes. -

Unique Wines - 840 Anything Not Covered in Above Classes

HOME WINE COMPETITION 2019 Competition Handbook Goal......................................................................................................... 2 General Information................................................................................ 2 2019 Calendar......................................................................................... 2 Wine Eligibility......................................................................................... 2 Awards.................................................................................................... 3 Current Sponsors: (Continually Updated) .............................................4 Shipping Or Hand-Delivery..................................................................... 7 Entry Rules............................................................................................ 10 Hand Delivering To Remote Location.................................................... 12 Judging Integrity.................................................................................... 12 Technical Advisory Panel...................................................................... 14 Wine Classes........................................................................................ 14 General Rules ......................................................................................17 Wine Glossary / Definitions................................................................... 18 Version 2019-1.0 Page !1 GOAL Our goal is to initiate and develop a stable amateur wine -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) the Ghost (Maquette), 1964 Painted Sheet Metal, Metal Rods, and Steel Wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.13

PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) The Ghost (maquette), 1964 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.13 Alexander Calder redefined sculpture in the 1940s by incorporating the element of movement. He created motorized works and later hanging sculptures, or “mobiles,” that rotate freely in response to airflow. Using wire, found objects, and industrial materials, Calder constructed three-dimensional line drawings of people, animals, and objects that he activated with kinetic verve. PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Performing Seal, 1950 Painted sheet metal and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.7 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Orange Paddle Under the Table, c. 1949 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.11 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Chat-mobile (Cat Mobile), 1966 Painted sheet metal and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.10 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Snowflakes and Red Stop, 1964 Painted sheet metal, metal rods, and steel wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.14 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Little Face, 1943 Copper wire, thread, glass, and wood Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.6 PB Alexander Calder (American, 1898–1976) Bird, 1952 Coffee cans, tin, and copper wire Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan, EL1995.8 PB Takis (Greek, b. 1925) Magnetic Mobile, c. 1964 Glass, plastic, wood, and electric cord Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Mrs. Robert B. Mayer, 1982.32 Since the 1950s, Greek artist and inventor Panayiotis “Takis” Vassilakis has investigated the relationship between art and science. -

Calder / Dubuffet Entre Ciel Et Terre Entre Ciel Et Terre © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /Preface Foreword

CALDER / DUBUFFET ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /PREFACE FOREWORD/ Opera Gallery Genève est heureuse de présenter une exposition exceptionnelle regroupant des œuvres de deux Opera Gallery Geneva is pleased to present an exceptional exhibition with works by two giants of the 20th century: géants du 20ème siècle : Alexander Calder et Jean Dubuffet. Au premier regard, leurs parcours et œuvres sont bien Alexander Calder and Jean Dubuffet. At first glance, their careers and work are very different, but a lot of elements différents, pourtant beaucoup d’éléments les rapprochent. draw them together. Ces deux artistes sont de la même génération mais ne se sont jamais rencontrés. Alexander Calder était These two artists are from the same generation but never met. Alexander Calder was American and Jean Dubuffet américain et Jean Dubuffet français. les deux ont vécu leurs vies artistiques des deux côtés de l’Atlantique. was French. Both have lived their artists’ lives travelling from one continent to the other. Both have been, at les deux ont été, au début de leurs carrières respectives, considérés comme des “outsiders” dans leurs propres the beginning of their respective careers considered as “outsiders” in their own country but their talent was pays mais leur talent a été immédiatement reconnu en France pour Calder et aux etats-Unis pour Dubuffet. immediately acknowledged in France for Calder and in America for Dubuffet. tous deux ont “révolutionné” l’art dit conventionnel grâce à une utilisation audacieuse de techniques et matériaux Both have revolutionized conventional art by an audacious use of informal techniques and materials. -

Referencing Alexander Calder: a Dialogue in Contemporary Chinese Art, on View from September 7 Through October 7, 2017

Referencing Alexander Calder: A Dialogue in Contemporary Chinese Art 525 West 22nd Street, New York September 7 – October 7, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, September 7, 6–8 PM Curated by Eli Klein Klein Sun Gallery is pleased to announce its ten year anniversary exhibition: Referencing Alexander Calder: A Dialogue in Contemporary Chinese Art, on view from September 7 through October 7, 2017. The exhibition includes selected works by Gao Ludi, Hong Hao, Hong Shaopei, Huang Rui, Jiang Pengyi, Li Jingxiong, Qin Jun, Shen Fan, Vivien Zhang, Yangjiang Group, and Zhao Yao. The gallery’s inaugural exhibition in 2007 Referencing Alexander Calder: A Dialogue in Modern and Contemporary Art consisted of unique works by modern artists such as Alexander Calder, Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró and Fernand Leger juxtaposed with the works of living artists such as Carmen Herrera, Joel Perlman, Monique Van Genderen and Amilcar de Castro. The overarching theme of the exhibition was Calder's art and its massive influence on his peers and contemporary artists. As a leader in the representation of Chinese contemporary art in the US for the past decade, Klein Sun Gallery now revisits its inaugural show. In ancient China, wind chimes were a fundamental part of Feng Shui where balances between Yin and Yang, flexibility and solidity, and movement and stability, were crucial. Alexander Calder is widely acknowledged as the originator of mobiles, a format within which he found a similar type of balance between the living and the mechanical. Calder encountered Chinese wind bells in his youth in San Francisco, influencing him from an early age. -

Development of Flavonoid Compounds in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Skins

Development of Flavonoid Compounds in Norton and Cabernet Sauvignon Grape Skins during Maturation A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science By NICOLE ELIZABETH DOERR Dr. Reid Smeda, Thesis Supervisor May 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the Thesis entitled DEVELOPMENT OF FLAVONOID COMPOUNDS IN NORTON AND CABERNET SAUVIGNON GRAPE SKINS DURING MATURATION Presented by Nicole Elizabeth Doerr A candidate for the degree of Master of Science And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Reid Smeda Professor Misha Kwasniewski Assistant Professor Wenping Qiu Adjunct Professor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisors, Dr. Reid Smeda and Dr. Misha Kwasniewski, for their willingness to take me on as a graduate student. Their insight and knowledge was extremely helpful these past couple of years in furthering my understanding of grape and wine. I would also like to thank my other committee member Dr. Wenping Qiu for his valuable insight. Additionally, I would like to thank all the past and present faculty, staff, and students of the Grape and Wine Institute. In particular, Dr. Anthony Peccoux and Dr. Ingolf Gruen, thank you for your guidance and encouragement. I would also like to thank Ashley Kabler for her help on my research projects. Thank you for your hard work, and friendship; without it I might still be picking and peeling berries. To my fellow graduate students: John, Ashley, Spencer, Tye, Andres, Hallie, Michael, Erin, and Jackie, thank you for your help with statistics, classes, papers, abstracts and presentations. -

Masterpiece: Mobiles by Alexander Calder

Masterpiece: Mobiles by Alexander Calder Keywords: Mobiles, Stabile, Kinetic Grade: 1st Grade Month: November Activity: Standing Mobile Meet the Artist and his work: Alexander Stirling Calder was born on July 22,1898, in Lawnton, Pennsylvania. He was the second child of artist parents—his father was a sculptor and his mother a painter. His friends called him Sandy. For Christmas in 1909, Calder presented his parents with two of his first sculptures, a tiny dog and duck cut from a brass sheet and bent into formation. The duck is kinetic—it rocks back and forth when tapped. Even at age eleven, his facility in handling materials was apparent. Despite his talents, Calder did not originally set out to become an artist. He instead enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology after high school and graduated in 1919 with an engineering degree. He undertook a series of jobs but remained unsatisfied with his career choice Calder decided to pursue an art career and moved to New York in 1923, enrolling at the Art Students League. He also took a job illustrating for the National Police Gazette. In the fall of 1931, a significant turning point in Calder's artistic career occurred when he created his first truly kinetic sculpture and gave form to an entirely new type of art. The first of these objects moved by systems of cranks and motors, and were dubbed "mobiles" by Marcel Duchamp—in French mobile refers to both "motion" and "motive." (If you have a baby brother or sister, they may have a mobile of brightly colored animals dancing above their crib.) Calder soon abandoned the mechanical aspects of these works when he realized he could fashion mobiles that would undulate on their own with the air's currents. -

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture

Press Release 13 July 2015 Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture 11 November 2015 – 3 April 2016 Tate Modern, Level 3 Supported by Terra Foundation for American Art with additional support from the Performing Sculpture Supporters Circle Open daily from 10.00 – 18.00 and until 22.00 on Friday and Saturday For public information call +44 (0)20 7887 8888, visit tate.org.uk, follow @tate #Calder Tate Modern presents the UK’s largest ever exhibition of Alexander Calder (1898-1976). Calder was one of the truly ground-breaking artists of the 20th century and as a pioneer of kinetic sculpture, played an essential role in shaping the history of modernism. Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture will bring together approximately 100 works to reveal how Calder turned sculpture from a static object into a continually changing work to be experienced in real time. Alexander Calder initially trained as an engineer before attending painting courses at the Arts Students League in New York. He travelled to Paris in the 1920s where he developed his wire sculptures and by 1931 had invented the mobile, a term first coined by Marcel Duchamp to describe Calder’s motorised objects. The exhibition traces the evolution of his distinct vocabulary - from his initial years captivating the artistic bohemia of inter-war Paris, to his later life spent between the towns of Roxbury in Connecticut and Saché in France. The exhibition will feature the figurative wire portraits Calder created of other artists including Joan Miró 1930 and Fernand Léger c.1930, alongside depictions of characters related to the circus, the cabaret and other mass spectacles of popular entertainment, including Two Acrobats 1929, The Brass Family 1929 and Aztec Josephine Baker c.1929. -

MW5 Layout 10

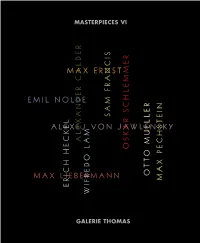

MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES VI MASTERPIECES VI GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS ALEXANDER CALDER UNTITLED 1966 6 MAX ERNST LES PEUPLIERS 1939 18 SAM FRANCIS UNTITLED 1964/ 1965 28 ERICH HECKEL BRICK FACTORY 1908 AND HOUSES NEAR ROME 1909 38 PARK OF DILBORN 191 4 50 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY HEAD OF A WOMAN c. 191 3 58 ABSTRACT HEAD: EARLY LIGHT c. 1920 66 4 WIFREDO LAM UNTITLED 1966 76 MAX LIEBERMANN THE GARDEN IN WANNSEE ... 191 7 86 OTTO MUELLER TW O NUDE GIRLS ... 191 8/20 96 EMIL NOLDE AUTUMN SEA XII ... 191 0106 MAX PECHSTEIN GREAT MILL DITCH BRIDGE 1922 11 6 OSKAR SCHLEMMER TWO HEADS AND TWO NUDES, SILVER FRIEZE IV 1931 126 5 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER sheet metal and wire, painted Provenance 1966 Galerie Maeght, Paris 38 .1 x 111 .7 x 111 .7 cm Galerie Marconi, Milan ( 1979) 15 x 44 x 44 in. Private Collection (acquired from the above in 1979) signed with monogram Private collection, USA (since 2 01 3) and dated on the largest red element The work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York under application number A25784. 8 UNTITLED 1966 ALEXANDER CALDER ”To most people who look at a mobile, it’s no more time, not yet become an exponent of kinetic art than a series of flat objects that move. To a few, in the original sense of the word, but an exponent though, it may be poetry.” of a type of performance art that more or less Alexander Calder invited the participation of the audience. -

19 Gifts from the Artist

n^ he Museum of Modern Art No. 15 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart FOR REIi^ASE: West Wednesday, February I, I967 PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, January 31, I967 11 a .IB. - U p.m. CALDER: I9 GIFTS FROM THE ARTIST, an exhibition of mobiles, stabiles, wood and wire sculptures and jewelry recently given to The Museum of Modern Art by the famous American artist, Alexander Calder, will be on view at the Museum from February 1 through April 5. The works in the exhibition range from Gaidar's early wire por traits of the I92O6, through various other periods and media, to a montanental mobile- stabile made in I96U. The 19 works by Calder, added to those already owned by the Museum, make this the largest and most complete collection by the artist in any museum. Thi# very geoerous gift caoe about in M^y I966 when Calder invited the Museum to make a choice from the contents of his Connecticut studio in recognition of the Museum's having given hin in 19i)3 bis first large retrospective exhibition« The major piece among Gaidar's recent gifts is Sandy's Butterfly, I96U, a great mobile-stabile of stainless steel painted red, white, black and yellow and standing nearly I3 feet high. Too tall to be shown indoors with the rest of the exhibition, this piece stands on the terrace just outside the Museum's Main Hall; it will later be moved to the upper terrace of the Sculpture Garden. Another work of the 1960s in the exhibition is a 2l^inch Model for "Teodelapio", the great steel stabile made in I962 for the Festival of Two Worlds at Spoleto, Italy. -

Search the List of Unclaimed Child Support

UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530. LAST NAME FIRST NAME MI ADDRESS CITY ABADIA CARMEN Y HOUSE A4 CEIBA ABARCA PAULA 7122 W OKANOGAN PLACE BLDG A KENNEWICK ABBOTT DONALD W 11600 ADENMOOR AVE DOWNEY ABERNATHY JACQUELINE 7722 W CONGRESS MILWAUKEE ABRAHAM PATRICIA 875 MILWAUKEE RD BELOIT ABREGO GERARDO A 1741 S 32ND ST MILWAUKEE ABUTIN MARY ANN P 1124 GRAND AVE WAUKEGAN ACATITLA JESUS 925 S 14TH ST SHEBOYGAN ACEVEDO ANIBAL 1409 POSEY AVE BESSEMER ACEVEDO MARIA G 1702 W FOREST HOME AVE MILWAUKEE ACEVEDO-VELAZQUEZ HUGO 119 S FRONT ST DORCHESTER ACKERMAN DIANE G 1939 N PORT WASHINGTON RD GRAFTON ACKERSON SHIRLEY K ADDRESS UNKNOWN MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CELIA C 5812 W MITCHELL ST MILWAUKEE ACOSTA CHRISTIAN 1842 ELDORADO DR APT 2 GREEN BAY ACOSTA JOE E 2820 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ACUNA ADRIAN R 2804 DUBARRY DR GAUTIER ADAMS ALIDA 4504 W 27TH AVE PINE BLUFF ADAMS EDIE 1915A N 21ST ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS EDWARD J 817 MELVIN AVE RACINE ADAMS GREGORY 7145 BENNETT AVE S CHICAGO ADAMS JAMES 3306 W WELLS ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS LINDA F 1945 LOCKPORT ST NIAGARA FALLS ADAMS MARNEAN 3641 N 3RD ST MILWAUKEE ADAMS NATHAN 323 LAWN ST HARTLAND ADAMS RUDOLPH PO BOX 200 FOX LAKE ADAMS TRACEY 104 WILDWOOD TER KOSCIUSKO ADAMS TRACEY 137 CONNER RD KOSCIUSKO ADAMS VIOLA K 2465 N 8TH ST LOWER MILWAUKEE ADCOCK MICHAEL D 1340 22ND AVE S #12 WIS RAPIDS ADKISSON PATRICIA L 1325 W WILSON AVE APT 1206 CHICAGO AGEE PHYLLIS N 2841 W HIGHLAND BLVD MILWAUKEE AGRON ANGEL M 3141 S 48TH ST MILWAUKEE AGUILAR GALINDO MAURICIO 110 A INDUSTRIAL DR BEAVER DAM AGUILAR SOLORZANO DARWIN A 113 MAIN ST CASCO AGUSTIN-LOPEZ LORENZO 1109A S 26TH ST MANITOWOC AKBAR THELMA M ADDRESS UNKNOWN JEFFERSON CITY ALANIS-LUNA MARIA M 2515 S 6TH STREET MILWAUKEE ALBAO LORALEI 11040 W WILDWOOD LN WEST ALLIS ALBERT (PAULIN) SHARON 5645 REGENCY HILLS DRIVE MOUNT PLEASANT ALBINO NORMA I 1710 S CHURCH ST #2 ALLENTOWN Page 1 of 138 UNCLAIMED CHILD SUPPORT AS OF 02/08/2021 TO RECEIVE A PAPER CLAIM FORM, PLEASE CALL WI SCTF @ 1-800-991-5530.