French Studies: the Post-Romantic Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oix-Progint Mise En Page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page1

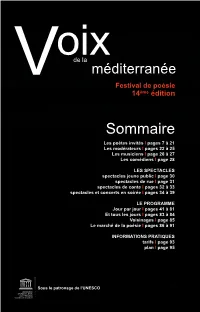

10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page1 oixde la V méditerranée Festival de poésie 14ème édition Sommaire Les poètes invités I pages 7 à 21 Les modérateurs I pages 22 à 25 Les musiciens I page 26 à 27 Les comédiens I page 28 LES SPECTACLES spectacles jeune public I page 30 spectacles de rue I page 31 spectacles de conte I pages 32 à 33 spectacles et concerts en soirée I pages 34 à 39 LE PROGRAMME Jour par jour I pages 41 à 81 Et tous les jours I pages 83 à 84 Voisinages I page 85 Le marché de la poésie I pages 86 à 91 INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES tarifs I page 93 plan I page 95 10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page2 2 10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page3 / édito Festival de poésie e 14 ous le patronage de l’UNESCO, le festival Voix de la Méditerranée va accueillir du 16 au 23 juillet, plus d’une centaine de poètes et Sd’artistes, conteurs, chanteurs et musiciens venus de toute la Méditerranée. A nouveau Lodève vivra du matin au soir au rythme de la poésie avec plus de 200 rendez-vous proposés à un public fidèle et curieux, conquis par l’atmosphère intime de la ville et la convivialité de la manifestation. Depuis 14 ans, l’invitation est lancée aux poètes, aux habitants du Voix de la Méditerranée / Voix territoire et à tous les festivaliers pour partager un temps d’échanges et de dialogue entre les cultures mais aussi entre les générations. -

3 July 2019 Royal Holloway, University of London

60th Annual Conference 1 - 3 July 2019 Royal Holloway, University of London Welcome and acknowledgments On behalf of the Society for French Studies, I am delighted to welcome all of you to our Annual Conference, this year hosted by Royal Holloway, University of London. Today's Royal Holloway is formed from two colleges, founded by two social pioneers, Elizabeth Jesser Reid and Thomas Holloway. We might note with some pleasure that they were among the first places in Britain where women could access higher education. Bedford College, in London, opened its doors in 1849, and Royal Holloway College's stunning Founder's Building was unveiled by Queen Victoria in 1886 – it’s still the focal point of the campus, and we shall gather there for a reception on Tuesday evening. In 1900, the colleges became part of the University of London and in 1985 they merged to form what is now known as Royal Holloway. We hope that this year’s offerings celebrate the full range of French Studies, and pay tribute to the contribution that is made more widely to Arts and Humanities research by the community of students and scholars who make up our discipline. We are especially pleased to welcome delegates attending the Society’s conference for the first time, as well as the many postgraduate students who will be offering papers and posters and colleagues from around the world. We are very excited to be welcoming the following keynote speakers to this year's conference: Kate Conley (Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Professor of French and Francophone Studies, William and Mary); David McCallam (Reader in French Eighteenth-Century Studies, University of Sheffield); Pap NDiaye (Professeur des universités à l'Institut d'études politiques de Paris, Histoire nord-américaine, Sciences-Po); and Mairéad Hanrahan (Professor of French, University College London and former President of SFS). -

Romanian Book Review Address of the Editorial Office : the Romanian Cultural Institute , Playwrights’ Club at the RCI Aleea Alexandru No

Published by the Romanian Cultural Institute Romanian ditorial by ANDREI Book REORIENMTARTGIOA NS IN EUROPE For several years now, there are percepti- ble cEhanges in our world. In the late eighties, liberal democracy continued the expansion started after World War II, at least in Europe. Meanwhile, national states have weakened, under the pressure to liberalize trade and the fight for recognition of minority (ethnic, poli- Review tical, sexual, etc.) movements. Globalization of the economy, communications, security, ISSUED MONTHLY G No. 5 G JUNE 2013 G DISTRIBUTED FOR FREE knowledge has become a reality. The financial crisis that broke out in 2008 surprised the world organized on market prin- ciples as economic regulator, and threatens to develop into an economic crisis with extended repercussions still hard to detect. U.S. last two elections favored the advocates of “change”, and the policy reorientation of the first world power does not remain without consequences for all mankind. On the stage of the producers of the world, China and Germany are now the first exporters. Russia lies among the powers that cannot be ignored in a serious political approach. (...) What happens, now? Facts cannot be cap- tured only by impressions, perceptions and occasional random experiences, even though many intellectuals are lured by them, produ- cing the barren chatter around us. Systematic TTThhhrrreeeeee DDDaaayyysss WWWiiittthhh thinking is always indispensable to those who want to actually understand what is going on . Not long ago, the famous National Intelligence Council, which, in the U.S., periodically offers interpretations of the global trends, published Global Report 2015 (2008). -

Métissage Et Narrativité Dans Trois Fictions Francophones L'enfant De Sable De Tahar BEN JELLOUN Solibo Magnifique De Patric

UNIVERSITÉ D’ORAN FACULTÉ DES LETTRES, LANGUES & ARTS ÉCOLE DOCTORALE DE FRANÇAIS Doctorat en sciences des textes littéraires Auteur : BOUTERFAS Bélabbas Métissage et Narrativité dans trois fictions francophones L’Enfant de sable de Tahar BEN JELLOUN Solibo Magnifique de Patrick CHAMOISEAU Le Diable en personne de Robert LALONDE Thèse dirigée par : me Directrice de thèse : M Christiane CHAULET-ACHOUR – Université Cergy- Pontoise – Co-directrice de thèse : Mme Nadia OUHIBI – Université d’Oran – Jury : Présidente de jury : Mme Fouzia BENJELLID – Université d’Oran – Examinateur : M. Hadj MILIANI – Université de Mostaganem – Examinateur : M. Bruno GELAS – Université Lyon II Examinateur : M. MEBARKI – Université d’Oran me Rapporteur : M Christiane CHAULET-ACHOUR Université Cergy-Pontoise Rapporteur : Mme Bahia OUHIBI – Université d’Oran – – Décembre 2008 – 1 Remerciements Une thèse de doctorat n’aboutit jamais sans l’aide scientifique, logistique et amicale de nombreuses personnes. Par ces remerciements, je tiens à exprimer ma profonde reconnaissance à ceux et celles qui m’ont aidé à réaliser ce travail de recherche. Leur disponibilité et leurs conseils m’ont été précieux. Que Madame Christiane CHAULET-ACHOUR trouve ici l’expression de ma sincère gratitude pour la confiance qu’elle m’a accordée dans la réalisation de ce travail, pour sa patience à suivre mes recherches et pour toute la rigueur qu’elle a su me transmettre à travers ses remarques. Mes remerciements vont aussi à Madame Ouhibi Nadia pour la compréhension qu’elle a manifestée et aux membres du jury : Mesdames Fouzia BENJELLID, Monsieur Hadj MILIANI, Je n’oublierai pas de remercier de tout cœur mes amis, ma famille, mes frères et ma soeur Nacéra, dont la présence à mes côtés a été d’un grand réconfort durant toutes ces années. -

Editions La Traductiere Catalog

1 éditions La Traductière Paris, 2017 Pour nouer encore plus solidement les distances bout à bout, La Traductière s’est lancée, en 2016, dans l’édition de livres. Profil : poésie en traduction. Champ d’action : domaine universel. Teneur : anthologies thématiques, anthologies d’auteur, recueils, revues. Accent d’intensité : du patrimoine à l’extrême contemporain. Notre principe, vous l’aurez compris, est de puiser dans les énormes réserves de la poésie contemporaine afin de la promouvoir en France et dans le monde francophone. Il ne me reste maintenant qu’à vous inviter à découvrir dans les pages du présent catalogue nos ovrages de la rentrée 2017. Auteurs incontournables et recrues de la nouvelle génération – un commando poétique. Linda Maria Baros 3 LITUANIE FRANÇAIS Domaine lituanien. Anthologie poèmes 80 pages La Traductière ISBN : 979-10-97304-05-8 préface et traduction par Jean-Baptiste Cabaud et Ainis Selena Cette anthologie est représentative des multiples mouvements qui traversent et constituent aujourd’hui la poésie lituanienne. Dainius Gintalas se situe à cheval entre le monde occidental et le monde slave. Plutôt dans une lignée de poèmes-fleuves, très rythmés, aux images fortes, il apporte à la poésie de son pays un côté radical. Giedrė Kazlauskaitė, très ancrée dans son époque, est féministe. Son écriture intellectuelle et religieuse s’affranchit volontiers de l’esthétique normée. Dovilė Kuzminskaitė s’inspire des formes et thématiques classiques, mais leur rajoute une dimension ludique et un regard d’une subtilité délicieuse. À la manière peut-être d’un Prévert en France, Liudvikas Jakimavičius oscille entre grande sensibilité poétique, humour et critique. -

PDF Du Livre

Femmes à l’œuvre dans la construction des savoirs Paradoxes de la visibilité et de l’invisibilité Caroline Trotot, Claire Delahaye et Isabelle Mornat (dir.) Éditeur : LISAA éditeur Lieu d'édition : Champs sur Marne Année d'édition : 2020 Date de mise en ligne : 18 septembre 2020 Collection : Savoirs en Texte ISBN électronique : 9782956648062 http://books.openedition.org Édition imprimée Nombre de pages : 340 Référence électronique TROTOT, Caroline (dir.) ; DELAHAYE, Claire (dir.) ; et MORNAT, Isabelle (dir.). Femmes à l’œuvre dans la construction des savoirs : Paradoxes de la visibilité et de l’invisibilité. Nouvelle édition [en ligne]. Champs sur Marne : LISAA éditeur, 2020 (généré le 18 septembre 2020). Disponible sur Internet : <http:// books.openedition.org/lisaa/1162>. ISBN : 9782956648062. © LISAA éditeur, 2020 Conditions d’utilisation : http://www.openedition.org/6540 Sous la direction de Caroline Trotot, Claire Delahaye, Isabelle Mornat Femmes à l’œuvre dans la construction des savoirs Paradoxes de la visibilité et de l’invisibilité Savoirs en texte Femmes à l’oeuvre dans la construction des savoirs Sous la direction de Savoirs en texte Caroline Trotot, Claire Delahaye, Isabelle Mornat Née du désir d’offrir un espace de publication entièrement numérique, ouvert à l’ensemble de la communauté scientifique, la collection « Savoirs en texte » publie des ouvrages collectifs ou des monographies soigneusement sélectionnés grâce à un processus d’expertise. Ses ouvrages abordent le savoir des textes, l’utilisation et la transformation de connaissances, de représentations, de modèles de pensée qu’ils soient issus des sciences humaines (histoire, sociologie, économie…) ou de domaines différents comme la physique, la biologie, la chimie… La collection est ouverte à des travaux qui mettent en œuvre des méthodes d’analyses diverses, soit pour étudier la genèse des représentations, l’intertextualité et le contexte culturel ou la poétique des textes. -

Le Mythe Du « Bon Paysan »

Le mythe du « Bon paysan » De l’utilisation politique d’une figure idéalisée Un travail de : Karel Ziehli [email protected] 079 266 16 57 Numéro d’immatriculation : 11-427-762 Master en Science Politique Mineur en Développement Durable Sous la direction du Prof. Dr. Marc Bühlmann Semestre d’automne 2018 Institut für Politikwissenschaft – Universität Bern Berne, le 8 février 2019 Figure 1 : Photographie réalisée par Gustave Roud, dans le cadre de son travail sur la paysannerie vau- doise (Source : https://loeildelaphotographie.com/fr/guingamp-gustave-roud-champscontre-champs-2016/) Universität Bern – Institut für Politikwissenschaft Karel Ziehli Travail de mémoire Automne 2018 « La méthode s’impose : par l’analyse des mythes rétablir les faits dans leur signification vraies. » Jean-Paul Sartre, 2011 : 13 An meine Omi, eine adlige Bäuerin 2 Universität Bern – Institut für Politikwissenschaft Karel Ziehli Travail de mémoire Automne 2018 Résumé La politique agricole est souvent décrite comme étant une « vache sacrée » en Suisse. Elle profite, en effet, d’un fort soutien au sein du parlement fédéral ainsi qu’auprès de la population. Ce soutien se traduit par des mesures protectionnistes et d’aides directes n’ayant pas d’équivalent dans les autres branches économiques. Ce statut d’exception, la politique agricole l’a depuis la fin des deux guerres mondiales. Ce présent travail s’in- téresse donc aux raisons expliquant la persistance de ce soutien. Il a été décidé de s’appuyer sur l’approche développée par Mayntz et Scharpf (2001) – l’institutionnalisme centré sur les acteurs – et de se pencher sur le mythe en tant qu’institution réglementant les interactions entre acteurs (March et Olsen, 1983). -

35E/35Th Festival Franco-Anglais De Poésie

35e/35th Festival franco-anglais de poésie - La Traductière 30 « L’attention poétique/Poetic Attention » Paris - juin 2012/Paris - June 2012 Invité d’honneur : SIngapour Special Guest: SINGAPORE Calendrier des activités/Activities Program Dimanche 10 juin à 11 heures/Sunday June 10 at 11 am : – Vidéopoèmes/Videopoems : Cinéma La Pagode (57 bis, rue de Babylone, Paris 7 e) Mardi 12 juin de 19 à 21 heures/Tuesday June 12 from 7 to 9 pm : – Lecture de poèmes/Poetry Reading : Café de Flore (172, bd Saint-Germain, Paris 6 e) Mercredi 13 juin/Wednesday June 13 : Galerie-Théâtre de Nesle (8,rue de Nesle, Paris 6e) – A 12 heures : Ouverture de l’exposition « Le lecteur de poésie », 1re partie At 12 noon: Opening of the exhibition “The Poetry Reader”, st1 part – A 20 h 30 : Soirée Poésie et Musique/At 8:30 pm: Poetry and Music Concert Jeudi 14 juin/Thursday June 14 : Marché de la poésie (place Saint-Sulpice, Paris 6e) – A 14 heures : Ouverture du Marché au public • A 17 h 30 sur le podium : Inauguration du Marché et du Festival avec Singapour • A 18 h 30 stand 114 : Inauguration de l’exposition « Le lecteur de poésie » 2e partie et lancement de La Traductière n° 30 • A 20 h sur le podium : Lecture « Nuit du Marché - Poésie de Singapour » n° 2 – At 2 pm: Opening of the Marché to the public • At 5:30 pm on the podium: Official Inauguration of the Marché and the Festival with Singapore • At 6:30 pm, stand 114: Opening of the exhibition “The Poetry Reader”, part 2 and launch of La Traductière Nr 30 • At 8 pm: Reading “Marché’s Night, Singapore Poetry -

Juillet-Août 2018

1 http://www.penclub.fr/ 6, rue François MIRON - 75 004 PARIS La lettre d’i nformation du PEN club français N°9 : JUILLET - AOÛT 2018 Sommaire Éditorial : Linda Maria Baros ………… ……………………………………………………. 3 Hommages à Georges - Emmanuel Clancier ………………………………………………… 4 L ’ interview du Président Emmanuel Pierrat ………………………………………………. 8 Du Comité des Écrivains persécutés – Andréas Becker …………………………… ... …… 13 Entretien avec Jennifer Clément …………………………………………………………… 39 Appel à action – Anniversaire de la mort de Daphné Caruana Galizia ………………… … 41 Le PEN Club français relayé par ActuaLitté .……………………………………………... 43 PEN international - Comité pour la Paix ……………………………………….………… 47 Colloque du 5 juin. Institut culturel italien de Paris…………………………….………… 48 Pluralisme et création à Bienne – Fulvio Caccia .………………………….……………… 53 Parlons traduction le 26 juin – David Ferré …………………………………….………….. 54 Le PEN Club français à Domme (24)………………………………………………… …… 57 2 Andréas Be cker en résidence à Brive (19)…………………………………………………. 59 Visite de deux membre s du Comité à José Correa (24)……………………………………. 63 Le PEN Club français chez Andr é Breton (46)……………………………………………. 65 É vé nements à veni r ………………………………………………………………………… 67 Les publication s …………………………………………………………………………… 72 3 Éditorial p ar Linda Mar ia BAROS Poète , membre du Comité directeur du Pen Club français, Vice - Présidente du Comité des droits des femmes Il y a des sous - sols où l’on découpe la littérature en tranches, où l’on amoncelle les livres, les quartiers de chair. Des sous - sols où l’on met en marche les bielles de l’obscurité avec des gestes translucides, mécaniques et froids. Il y a cette rage infinie qui taille avec un burin la chair et les os, pour donner à celui qui écrit un nouveau visage. Qui brise ses rotules, ses pieds, pour qu’il s’écroule, qu’il tombe à genoux. -

Zbornik Vilenica 2017

32. Mednarodni literarni festival 32nd International Literary Festival LITERATURA, KI SPREMINJA SVET, KI SPREMINJA LITERATURO LITERATURE THAT CHANGES THE WORLD THAT CHANGES LITERATURE Vilenica 2017 32. Mednarodni literarni festival Vilenica / 32nd Vilenica International Literary Festival Vilenica 2017 © Nosilci avtorskih pravic so avtorji sami, če ni navedeno drugače. © The authors are the copyright holders of the text unless otherwise stated. Uredili / Edited by Kristina Sluga, Maja Kavzar Hudej Založilo in izdalo Društvo slovenskih pisateljev, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Zanj Ivo Svetina, predsednik Issued and published by the Slovene Writers’ Association, Tomšičeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana Ivo Svetina, President Jezikovni pregled / Proofreading Jožica Narat, Jason Blake Življenjepisi v slovenščini / English Translation Kristina Sluga, Petra Meterc Grafično oblikovanje naslovnice / Cover design Barbara Bogataj Kokalj Prelom / Layout Klemen Ulčakar Tehnična ureditev in tisk / Technical editing and print Ulčakar grafika Naklada / Print run 300 izvodov / 300 copies Ljubljana, avgust 2017 / August 2017 Zbornik je izšel s finančno podporo Javne agencije za knjigo Republike Slovenije. The almanac was published with the financial support of the Slovenian Book Agency. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 7.079:82(497.4Vilenica)”2017”(082) MEDNARODNI literarni festival (32 ; 2017 ; Vilenica) Vilenica : literatura, ki spreminja svet, ki spreminja literaturo = literature that changes the world that changes -

1 Mednarodni Lirikonfest Velenje

Mednarodni Lirikonfest Velenje 2002–2017_predstavitev17fvk2 V17-2_ist 30/6-17sr // kv 29/8-17 Predstavitev festivala www.lirikonfest-velenje.si MEDNARODNI LIRIKONFEST VELENJE International Lirikonfest Velenje Das internationale Lirikonfest Velenje 1 Lirikonfestovo podnebje / rezervat za poezijo festival liričnega in potopisnega občutja (21. marec–21. junij :: od cvetenja do zorenja češenj) ŠESTNAJST LET KNJIŽEVNO USTVARJALNIH (2001/2002–2017) MEDNARODNI LIRIKONFEST VELENJE :: www.lirikonfest-velenje.si rezervat za poezijo :: pomladni festival liričnega in potopisnega občutja (21. marec–21. junij :: od cvetenja do zorenja češenj) Mednarodno književno srečanje v Velenju Mednarodni Lirikonfest Velenje (MLFV) je tradicionalni celoletni literarni fe- stival liričnih umetnosti XXI. st. – z osrednjim programom mednarodnega književ- 2 nega srečanja v Velenju (v juniju ali septembru) –, ki ga od leta 2002 (do 2007 imeno- van »Herbersteinsko srečanje slovenskih književnikov z mednarodno udeležbo«) organizirata Ustanova Velenjska knjižna fundacija (UVKF) in asociacija Velenika v sodelovanju s tujimi in slovenskimi partnerji. Pobudnik ustanovitve, programski in organizacijski vodja festivala je književnik Ivo Stropnik. Mednarodni Lirikonfest Velenje (»rezervat za poezijo«, »festival liričnega ob- čutja«) je že poldrugo desetletje vpet v predstavitve in popularizacijo umetniške lite- rature XXI. st., njenih ustvarjalcev, prevajalcev, mednarodnih posrednikov slovenske literature in jezika drugim narodom, organizatorjev, urednikov idr. poznavalcev slo- -

Society for French Studies, Royal Holloway, 1-3 July 2019 Provisional Programme

Society for French Studies, Royal Holloway, 1-3 July 2019 Provisional Programme Monday 1 July 11.00am- Conference Registration for all delegates Residential delegates check into accommodation 12.00-1.00pm A. Session for Postgraduate Students: Meet the Editors B. AUPHF AGM 12.30-1.30pm Buffet lunch for all delegates 1.30-3.00pm Presidential Welcome Judith Still (University of Nottingham) Hannah Thompson (RHUL) Plenary Lecture One Chair: tbc Kate Conley (Dean of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, Professor of French and Francophone Studies, William and Mary) Collection as a Surrealist State of Mind 3.00-4.30pm PANEL SESSIONS ONE (1.1) New Readings of Feminisms Chair: tbc Notes on the Present Tense: Temporal Regimes and Trauma in Contemporary French Women’s Writing Adina Stroia (University College London/IMLR) Monique Wittig’s Call to Arms Catherine Burke (University College Cork) Monique Wittig’s Les Guérillères at 50: Echoes with #MeToo Sandra Daroczi (University of Bath) (1.2) Sound and Prose Chair: Emily Kate Price (University of Cambridge) Troubadours and Trouvères in Prose: Comments on Richard de Fournival’s Bestiaire d’amours Elizabeth Eva Leach (University of Oxford) Song in Prose: The Case of Saint-Loup’s Last Words in Proust’s Le Temps retrouvé Jennifer Rushworth (University College London) Sounding Literature: Music and the Animal Cry in Cixous’s Jours de l’an Naomi Waltham-Smith (University of Warwick) (1.3) Migration and Mobility 1: Alain Mabankou Chair: tbc L'humour dans Black Bazar d'Alain Mabanckou : une réponse esthétique et subversive à la 'crise des catégories’ Constance Vottero (Boston University) Migration and Invention in the Paris novels of Alain Mabanckou Emelyn Lih (New York University) Poétique d’une « réalité praxique » du récit migratoire dans Le Monde est mon langage d’Alain Mabanckou Emmanuel M.