Attractive Nuisances in Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

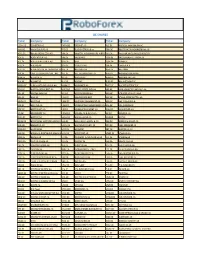

R Trader Instruments Cfds and Stocks

DE SHARES Ticker Company Ticker Company Ticker Company 1COV.DE COVESTRO AG FNTN.DE FREENET AG P1Z.DE PATRIZIA IMMOBILIEN AG AAD.DE AMADEUS FIRE AG FPE.DE FUCHS PETROLUB vz PBB.DE DEUTSCHE PFANDBRIEFBANK AG ACX1.DE BET-AT-HOME.COM AG FRA.DE FRAPORT AG FRANKFURT AIRPORTPFV.DE PFEIFFER VACUUM TECHNOLOGY ADJ.DE ADO PROPERTIES FRE.DE FRESENIUS PSM.DE PROSIEBENSAT.1 MEDIA SE ADL.DE ADLER REAL ESTATE AG G1A.DE GEA PUM.DE PUMA SE ADS.DE ADIDAS AG G24.DE SCOUT24 AG QIA.DE QIAGEN N.V. ADV.DE ADVA OPTICAL NETWORKING SE GBF.DE BILFINGER SE RAA.DE RATIONAL AFX.DE CARL ZEISS MEDITEC AG - BR GFT.DE GFT TECHNOLOGIES SE RHK.DE RHOEN-KLINIKUM AG AIXA.DE AIXTRON SE GIL.DE DMG MORI RHM.DE RHEINMETALL AG ALV.DE ALLIANZ SE GLJ.DE GRENKE RIB1.DE RIB SOFTWARE SE AM3D.DE SLM SOLUTIONS GROUP AG GMM.DE GRAMMER AG RKET.DE ROCKET INTERNET SE AOX.DE ALSTRIA OFFICE REIT-AG GWI1.DE GERRY WEBER INTL AG S92.DE SMA SOLAR TECHNOLOGY AG ARL.DE AAREAL BANK AG GXI.DE GERRESHEIMER AG SAX.DE STROEER SE & CO KGAA BAS.DE BASF SE HAB.DE HAMBORNER REIT SAZ.DE STADA ARZNEIMITTEL AG BAYN.DE BAYER AG HBM.DE HORNBACH BAUMARKT AG SFQ.DE SAF HOLLAND S.A. BC8.DE BECHTLE AG HDD.DE HEIDELBERGER DRUCKMASCHINENSGL.DE SGL CARBON SE BDT.DE BERTRANDT AG HEI.DE HEIDELBERGCEMENT AG SHA.DE SCHAEFFLER AG BEI.DE BEIERSDORF AG HEN3.DE HENKEL AG & CO KGAA SIE.DE SIEMENS AG BIO4.DE BIOTEST AG HLAG.DE HAPAG-LLOYD AG SIX2.DE SIXT SE BMW.DE BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE AGHLE.DE HELLA KGAA HUECK & CO SKB.DE KOENIG & BAUER AG BNR.DE BRENNTAG AG HNR1.DE HANNOVER RUECK SE SPR.DE AXEL SPRINGER SE BOSS.DE HUGO BOSS -

Market Cap Close ADV 1598 67Th Pctl 745,214,477.91 $ 23.96

Market Cap Close ADV 1598 67th Pctl $ 745,214,477.91 $ 23.96 225,966.94 801 33rd Pctl $ 199,581,478.89 $ 10.09 53,054.83 2399 Ticker_ Listing_ Effective_ Revised Symbol Security_Name Exchange Date Mkt Cap Close ADV Stratum Stratum AAC AAC Holdings, Inc. N 20160906 M M M M-M-M M-M-M AAMC Altisource Asset Management Corp A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L AAN Aarons Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AAV Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd N 20160906 H L M H-L-M H-M-M AB Alliance Bernstein Holding L P N 20160906 H M M H-M-M H-M-M ABG Asbury Automotive Group Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H ABM ABM Industries Inc. N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AC Associated Capital Group, Inc. N 20160906 H H L H-H-L H-H-L ACCO ACCO Brand Corp. N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H ACU Acme United A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L ACY AeroCentury Corp A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADK Adcare Health System A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADPT Adeptus Health Inc. N 20160906 M H H M-H-H M-H-H AE Adams Res Energy Inc A 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L AEL American Equity Inv Life Hldg Co N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AF Astoria Financial Corporation N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AGM Fed Agricul Mtg Clc Non Voting N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AGM A Fed Agricultural Mtg Cla Voting N 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L AGRO Adecoagro S A N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H AGX Argan Inc N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AHC A H Belo Corp N 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L AHL ASPEN Insurance Holding Limited N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AHS AMN Healthcare Services Inc. -

Market Cap Close ADV

Market Cap Close ADV 1598 67th Pctl $745,214,477.91 $23.96 225,966.94 801 33rd Pctl $199,581,478.89 $10.09 53,054.83 2399 Listing_ Revised Ticker_Symbol Security_Name Exchange Effective_Date Mkt Cap Close ADV Stratum Stratum AAC AAC Holdings, Inc. N 20160906 M M M M-M-M M-M-M Altisource Asset Management AAMC Corp A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L AAN Aarons Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AAV Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd N 20160906 H L M H-L-M H-M-M AB Alliance Bernstein Holding L P N 20160906 H M M H-M-M H-M-M ABG Asbury Automotive Group Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H ABM ABM Industries Inc. N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AC Associated Capital Group, Inc. N 20160906 H H L H-H-L H-H-L ACCO ACCO Brand Corp. N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H ACU Acme United A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L ACY AeroCentury Corp A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADK Adcare Health System A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADPT Adeptus Health Inc. N 20160906 M H H M-H-H M-H-H AE Adams Res Energy Inc A 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L American Equity Inv Life Hldg AEL Co N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AF Astoria Financial Corporation N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AGM Fed Agricul Mtg Clc Non Voting N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AGM A Fed Agricultural Mtg Cla Voting N 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L AGRO Adecoagro S A N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H AGX Argan Inc N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AHC A H Belo Corp N 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ASPEN Insurance Holding AHL Limited N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AHS AMN Healthcare Services Inc. -

September 2014 M&A and Investment Summary

September 2014 M&A and Investment Summary Expertise. Commitment. Results. Table of Contents 1 Overview of Monthly M&A and Investment Activity 3 2 Monthly M&A and Investment Activity by Industry Segment 9 3 Additional Monthly M&A and Investment Activity Data 42 4 About Petsky Prunier 57 Securities offered through Petsky Prunier Securities, LLC, member of FINRA. This M&A and Investment Summary has been prepared by and is being distributed in the United States by Petsky Prunier, a broker dealer register with the U.S. SEC and a member of FINRA. Petsky Prunier is not affiliated with Altium Capital Ltd, but has partnered with Altium to expand its international presence. Altium has not prepared or verified the information in this Summary. Persons in the United States should contact Petsky Prunier for further information or services. This M&A and Investment Summary is not being distributed by Altium Capital Ltd in the United States and Altium Capital Ltd is not offering any services to persons in the United States. 2| M&A and Investment Summary September 2014 M&A and Investment Summary for All Segments Transaction Distribution . A total of 428 deals were announced in September 2014, of which 236 were worth $37.5 billion in aggregate reported value . Software was the most active and highest reported value segment with 92 deals announced, of which 46 were reported at $13.5 billion in aggregate value . Digital Media/Commerce was another active segment with 85 transactions that were worth $4.5 billion . Strategic buyers announced 197 deals (46 percent of total volume), of which 40 were worth $24.9 billion in aggregate value . -

Hamilton Lane Incorporated Nps 2021 V3

110 Washington Street Suite 1300 Conshohocken, PA 19428 Telephone: (610) 934-2222 July 22, 2021 Fellow Stockholders: You are cordially invited to attend our 2021 Annual Meeting of Stockholders, which will be held via live audio webcast on Thursday, September 2, 2021 at 9:30 a.m. (Eastern Time). All Hamilton Lane Incorporated stockholders of record at the close of business on July 7, 2021 are welcome to attend the Annual Meeting, but it is important that your shares are represented at the Annual Meeting whether or not you plan to attend. To ensure that you will be represented, we ask you to vote by telephone, mail or over the Internet. Hamilton Lane continues to monitor public health and safety concerns related to the coronavirus (“COVID-19”) pandemic and the various measures being implemented to reduce its impact, including recommendations and protocols issued by public health authorities and federal, state, and local governments. In light of these concerns and to support the health and well-being of our employees and stockholders, the Annual Meeting will be a virtual meeting of stockholders conducted via live audio webcast. You will be able to attend and participate in the Annual Meeting online by visiting www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/ HLNE2021 at the meeting date and time described above and in the accompanying proxy statement and by entering the 16-digit control number that appears on your Notice of Internet Availability of Proxy Materials or, if you received a paper copy of the proxy materials, your proxy card (printed in the box and marked by the arrow) or the instructions that accompanied your proxy materials. -

Payments / Banking

Financial Technology Sector Summary June 24, 2015 Financial Technology Sector Summary Table of Contents I. GCA Savvian Overview II. Market Summary III. Payments / Banking IV. Securities / Capital Markets / Data & Analytics V. Healthcare / Insurance I. GCA Savvian Overview GCA Savvian Overview Highlights Firm Statistics GCA Savvian Focus . Over 225 professionals today Mergers & Acquisitions Private Capital Markets . Full spectrum of buy-side, sell- Agented private capital raiser Headquarters in San Francisco and Tokyo; offices in New side and strategic advisory York, London, Shanghai, Mumbai, Singapore, and Osaka . Equity and debt capital markets . Public and private company advisory services experience . Provides mergers and acquisitions advisory services, private . Core competency, with important capital & capital markets advisory services, and principal . Strategic early-stage growth relationships among the venture investing companies through industry capital and private equity defining, multi-billion dollar community transactions . Over 550 transactions completed . Publicly traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (2174) Senior level attention and focus, Relationships and market extensive transaction intelligence; a highly experienced team in experience and deep domain insight the industry Global Advisory Firm Market Positioning Bulge Bracket Growth Sector Focus Transaction Expertise . Senior Team with . Growth Company Focus Unparalleled Transaction . Sector Expertise / Domain Experience Knowledge . Highest Quality Client . Private Capital -

Deloitte's Technology Fast

Deloitte’s 2015 Technology Fast 500™ Powerful connections @DeloitteTMT #Fast500 ANNUAL RANKING OF THE FASTEST GROWING TECHNOLOGY COMPANIES IN NORTH AMERICA About Deloitte’s Technology Fast 500 About Deloitte’s Technology Fast 500 The Technology Fast 500 is the leading technology awards program in North America (U.S. and Canada) with 2015 being its twenty-first year. Combining technological innovation, entrepreneurship and rapid growth, Fast 500 companies — large, small, public, and private — span a variety of industry sectors. These companies are on the cutting edge and are transforming the way we do business today. Selection and qualifying criteria The Technology Fast 500 provides a ranking of the fastest growing technology, media, telecommunications, life sciences and energy tech companies — both public and private — in North America (U.S. and Canada). Technology Fast 500 award winners for 2015 are selected based on percentage fiscal year revenue growth during the period from 2011 to 2014. In order to be eligible for Technology Fast 500 recognition, companies must own proprietary intellectual property or technology that is sold to customers in products that contribute to a majority of the company’s operating revenues. Companies must have base-year (2011) operating revenues of at least $50,000 USD or CD, and current-year (2014) operating revenues of at least $5 million USD or CD. Additionally, companies must be in business for a minimum of four years, and be headquartered within North America. This ranking is compiled from applications submitted directly to the Technology Fast 500 Web site, and public company database research conducted by Deloitte LLP. -

MARKSTON INTERNATIONAL LLC Form 13F-HR Filed 2021-05-14

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 13F-HR Initial quarterly Form 13F holdings report filed by institutional managers Filing Date: 2021-05-14 | Period of Report: 2021-03-31 SEC Accession No. 0001089991-21-000002 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER MARKSTON INTERNATIONAL LLC Mailing Address Business Address 50 MAIN STREET 50 MAIN STREET CIK:1089991| IRS No.: 134053806 | State of Incorp.:NY | Fiscal Year End: 1231 WHITE PLAINS NY 10606 WHITE PLAINS NY 10606 Type: 13F-HR | Act: 34 | File No.: 028-04869 | Film No.: 21923307 9147614700 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document OMB APPROVAL UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE OMB Number: 3235-0006 COMMISSION Expires: July 31, 2015 Washington, D.C. 20549 Estimated average burden hours per response: 23.8 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: 03-31-2021 Check here if Amendment: ☐ Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): ☐ is a restatement. ☐ adds new holdings entries. Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: MARKSTON INTERNATIONAL LLC Address: 50 MAIN STREET WHITE PLAINS, NY 10606 Form 13F File Number: 028-04869 The institutional investment manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed hereby represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Chris Mullarkey Title: Managing Member Phone: 914-761-4700 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: Chris Mullarkey White Plains, NEW YORK 05-14-2021 [Signature] [City, State] [Date] Report Type (Check only one.): ☒ 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. -

Software Equity Group Flash Report

Software Equity Group Flash Report Select M&A Transactions and Valuations and Financial and Valuation Performance of 250+ Publicly Traded Software, SaaS and Internet Companies by Product Category October 2014 LEADERS IN SOFTWARE M&A • Industry leading boutique investment bank, founded in 1992, representing public and private software and We Do Deals. internet companies seeking: • Strategic exit • Growth capital • Buyout • Inorganic growth via acquisition • Buy and sell-side mentoring • Fairness opinions and valuations • Sell-side client revenue range: $5 - 75 million • Buy-side clients include private equity firms and NASDAQ, NYSE and foreign exchange listed companies • Clients span virtually every software technology, product category, delivery model and vertical market • Global presence providing advice and guidance to more than 2,000 private and public companies throughout US, Canada, Europe, Asia-Pacific, Africa and Israel • Strong cross-functional team leveraging transaction, operating, legal and engineering experience • Unparalleled software industry reputation and track record. • Highly referenceable base of past clients Copyright © 2014 by Software Equity Group, LLC EXTENSIVE GLOBAL REACH Current Sell-side Representation • SEG currently represents software companies in the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Australia & Saudi Arabia Recent Sell-side Representation • In addition to the countries listed above, SEG has recently represented software companies in the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, Israel, and South Africa SEG Research Distribution • SEG’s Quarterly and Annual Software Industry Equity Reports and Monthly Flash Reports are distributed to an opt-in list of 50,000 public software company CEOs, software entrepreneurs, private equity managing directors, VCs, high tech corporate lawyers, public accountants, etc. in 76 countries. -

Software Equity Group Flash Report

Software Equity Group Flash Report Select M&A Transactions and Valuations and Financial and Valuation Performance of 250+ Publicly Traded Software, SaaS and Internet Companies by Product Category October 2014 LEADERS IN SOFTWARE M&A • Industry leading boutique investment bank, founded in 1992, representing public and private software and We Do Deals. internet companies seeking: • Strategic exit • Growth capital • Buyout • Inorganic growth via acquisition • Buy and sell-side mentoring • Fairness opinions and valuations • Sell-side client revenue range: $5 - 75 million • Buy-side clients include private equity firms and NASDAQ, NYSE and foreign exchange listed companies • Clients span virtually every software technology, product category, delivery model and vertical market • Global presence providing advice and guidance to more than 2,000 private and public companies throughout US, Canada, Europe, Asia-Pacific, Africa and Israel • Strong cross-functional team leveraging transaction, operating, legal and engineering experience • Unparalleled software industry reputation and track record. • Highly referenceable base of past clients Copyright © 2014 by Software Equity Group, LLC EXTENSIVE GLOBAL REACH Current Sell-side Representation • SEG currently represents software companies in the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Australia & Saudi Arabia Recent Sell-side Representation • In addition to the countries listed above, SEG has recently represented software companies in the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands, Israel, and South Africa SEG Research Distribution • SEG’s Quarterly and Annual Software Industry Equity Reports and Monthly Flash Reports are distributed to an opt-in list of 50,000 public software company CEOs, software entrepreneurs, private equity managing directors, VCs, high tech corporate lawyers, public accountants, etc. in 76 countries. -

Wharton Future of Advertising Program 2016/17 Annual Stewardship Report

wharton future of advertising program 2016/17 Annual Stewardship Report Jerry Wind • Catharine Hays WFOA.UPENN.EDU • @WHARTONFOA 1 table of contents KNOWLEDGE GENERATION THROUGH COLLABORATION 5 KNOWLEDGE DISSEMINATION AND VISIBILITY 13 INFLUENCE AND IMPACT 16 WFOA EDUCATION 20 APPENDIx I: WFOa innovation network 27 appendix II: published articles, blogs, and media 35 mentions Appendix III: WFOA strategic collaborations 39 Appendix IV: creating and activating wfoa touchpoints 48 2 his Report serves as both an overview of the Program’s recent achievements, as Twell as a celebration of the individuals in our academic/practitioner community who have made this imporant knowledge co-creation and dissemination possible. The 2016-17 WFoA Stewardship Report highlights the Program’s commitment and to drive and support deeper insights, bolder innovation and broader positive impact of advertising and marketing for business, people, and society. 3 rom 2008 through 2017, The Wharton Future of Advertising Program acted fas a catalyst to launch the forces of change and make advertising and marketing markedly better for businesses, people, and society. WFoA was at its core a growing global network of forward-thinking, reflective, open-minded, interdisciplinary academic and industry collaborators. 4 Beyond Advertising and the advertising 6 2020 project 2016 Annual meeting in london 8 MARKETING MATTERS RADIO SHOW AND 9 PODCAST media future summits 11 2016 cannes lions 12 I: knowledge generation through collaboration Projects and initiatives that deepen and share our understanding of the ongoing challenges and opportunities facing practitioners today, and offer guidance for the way forward 5 “[beyond advertising] is a must-read for anyone who wants to be effective in reaching, influencing, and creating value. -

6750-01 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Granting of Request

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 11/17/2014 and available online at http://federalregister.gov/a/2014-27025, and on FDsys.gov BILLING CODE: 6750-01 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Granting of Request for Early Termination of the Waiting Period Under the Premerger Notification Rules Section 7A of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. 18a, as added by Title II of the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, requires persons contemplating certain mergers or acquisitions to give the Federal Trade Commission and the Assistant Attorney General advance notice and to wait designated periods before consummation of such plans. Section 7A(b)(2) of the Act permits the agencies, in individual cases, to terminate this waiting period prior to its expiration and requires that notice of this action be published in the Federal Register. The following transactions were granted early termination -- on the dates indicated -- of the waiting period provided by law and the premerger notification rules. The listing for each transaction includes the transaction number and the parties to the transaction. The grants were made by the Federal Trade Commission and the Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice. Neither agency intends to take any action with respect to these proposed acquisitions during the applicable waiting period. Early Terminations Granted October 1, 2014 thru October 31, 2014 10/01/2014 20141617 G Nucor Corporation; Gerdau S.A.; Nucor Corporation 10/02/2014 20141591 G Deutsche Telekom AG; AT&T Inc.; Deutsche Telekom AG 20141592 G AT&T Inc.; Deutsche Telekom AG; AT&T Inc.