National Venture Capital Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Premise Vs. Cloud

WHITEPAPER Content Management for Mobile Devices: Smartphones, Use Cases and Best Practices in a Mobile-Centric World JULY 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Mobile-Delivered Content Is Growing Globally 3 Start with Smartphones 4 Challenges and Opportunities 5 Use Cases Drive Mobile Content Strategy 6 Overcoming Barriers To Implementation 7 Best Practices: Build For Success 8 Conclusions 9 About CrownPeak 10 2 Executive Summary In an environment where mobile web traffic tripled last year and mobile data users are expected to outpace desktop users by next year, the need for mobile-optimized content management is clear. Yet implementing content management systems has traditionally been a slow and resource-intensive process. One emerging strategy for successfully deploying mobile content is to focus on optimizing for smartphones, which offer both the largest and most stable mobile development platform. This approach has already proven successful in a number of market sectors and offers the advantages of simplicity, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness. A second strategy has been to leverage the new generation of Web Content Management systems. These systems combine breakthroughs in productivity with the ability to natively optimize content for mobile delivery, they work seamlessly with legacy systems, and typically do not require IT resources. The result is a significantly lower implementation and operation costs when compared to traditional content management solutions. Web Content Management (WCM) systems have traditionally been both time- and cost-intensive, requiring significant resources from expert developers and in- house IT. This paper recommends adoption of such a smartphone-centric strategy with a next-generation WCM to create a flexible, scalable, interoperable mobile content management solution, without impacting legacy systems or compromising data integrity. -

Financing Transactions 12

MOBILE SMART FUNDAMENTALS MMA MEMBERS EDITION AUGUST 2012 messaging . advertising . apps . mcommerce www.mmaglobal.com NEW YORK • LONDON • SINGAPORE • SÃO PAULO MOBILE MARKETING ASSOCIATION AUGUST 2012 REPORT MMA Launches MXS Study Concludes that Optimal Spend on Mobile Should be 7% of Budget COMMITTED TO ARMING YOU WITH Last week the Mobile Marketing Association unveiled its new initiative, “MXS” which challenges marketers and agencies to look deeper at how they are allocating billions of ad THE INSIGHTS AND OPPORTUNITIES dollars in their marketing mix in light of the radically changing mobile centric consumer media landscape. MXS—which stands for Mobile’s X% Solution—is believed to be the first YOU NEED TO BUILD YOUR BUSINESS. empirically based study that gives guidance to marketers on how they can rebalance their marketing mix to achieve a higher return on their marketing dollars. MXS bypasses the equation used by some that share of time (should) equal share of budget and instead looks at an ROI analysis of mobile based on actual market cost, and current mobile effectiveness impact, as well as U.S. smartphone penetration and phone usage data (reach and frequency). The most important takeaways are as follows: • The study concludes that the optimized level of spend on mobile advertising for U.S. marketers in 2012 should be seven percent, on average, vs. the current budget allocation of less than one percent. Adjustments should be considered based on marketing goal and industry category. • Further, the analysis indicates that over the next 4 years, mobile’s share of the media mix is calculated to increase to at least 10 percent on average based on increased adoption of smartphones alone. -

Internet Economy 25 Years After .Com

THE INTERNET ECONOMY 25 YEARS AFTER .COM TRANSFORMING COMMERCE & LIFE March 2010 25Robert D. Atkinson, Stephen J. Ezell, Scott M. Andes, Daniel D. Castro, and Richard Bennett THE INTERNET ECONOMY 25 YEARS AFTER .COM TRANSFORMING COMMERCE & LIFE March 2010 Robert D. Atkinson, Stephen J. Ezell, Scott M. Andes, Daniel D. Castro, and Richard Bennett The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation I Ac KNOW L EDGEMEN T S The authors would like to thank the following individuals for providing input to the report: Monique Martineau, Lisa Mendelow, and Stephen Norton. Any errors or omissions are the authors’ alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr. Robert D. Atkinson is President of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Stephen J. Ezell is a Senior Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Scott M. Andes is a Research Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Daniel D. Castro is a Senior Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Richard Bennett is a Research Fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. ABOUT THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION FOUNDATION The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is a Washington, DC-based think tank at the cutting edge of designing innovation policies and exploring how advances in technology will create new economic opportunities to improve the quality of life. Non-profit, and non-partisan, we offer pragmatic ideas that break free of economic philosophies born in eras long before the first punch card computer and well before the rise of modern China and pervasive globalization. ITIF, founded in 2006, is dedicated to conceiving and promoting the new ways of thinking about technology-driven productivity, competitiveness, and globalization that the 21st century demands. -

Inprs Cafr Fy20 Working Version

COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORREPORTT 2020 For the FiscalFiscal YearYear EndedEnded JuneJune 30,30, 20202019 INPRS is a component unit and a pension trust fund of the State of Indiana. The Indiana Public Retirement System is a component Prepared through the joint efforts of INPRS’s team members. unit and a pension trust fund of the State of Indiana. Available online at www.in.gov/inprs COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2020 For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2020 INPRS is a component unit and a pension trust fund of the State of Indiana. INPRS is a trust and an independent body corporate and politic. The system is not a department or agency of the state, but is an independent instrumentality exercising essential governmental functions (IC 5-10.5-2-3). FUNDS MANAGED BY INPRS ABBREVIATIONS USED Defined Benefit DB Fund 1. Public Employees’ Defined Benefit Account PERF DB 2. Teachers’ Pre-1996 Defined Benefit Account TRF Pre-’96 DB 3. Teachers’ 1996 Defined Benefit Account TRF ’96 DB 4. 1977 Police Officers’ and Firefighters’ Retirement Fund ’77 Fund 5. Judges’ Retirement System JRS 6. Excise, Gaming and Conservation Officers’ Retirement Fund EG&C 7. Prosecuting Attorneys’ Retirement Fund PARF 8. Legislators’ Defined Benefit Fund LE DB Defined Contribution DC Fund 9. Public Employees’ Defined Contribution Account PERF DC 10. My Choice: Retirement Savings Plan for Public Employees PERF MC DC 11. Teachers’ Defined Contribution Account TRF DC 12. My Choice: Retirement Savings Plan for Teachers TRF MC DC 13. Legislators’ Defined Contribution Fund LE DC Other Postemployement Benefit OPEB Fund 14. -

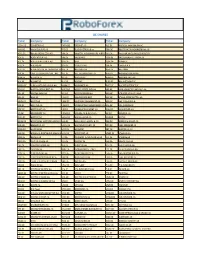

R Trader Instruments Cfds and Stocks

DE SHARES Ticker Company Ticker Company Ticker Company 1COV.DE COVESTRO AG FNTN.DE FREENET AG P1Z.DE PATRIZIA IMMOBILIEN AG AAD.DE AMADEUS FIRE AG FPE.DE FUCHS PETROLUB vz PBB.DE DEUTSCHE PFANDBRIEFBANK AG ACX1.DE BET-AT-HOME.COM AG FRA.DE FRAPORT AG FRANKFURT AIRPORTPFV.DE PFEIFFER VACUUM TECHNOLOGY ADJ.DE ADO PROPERTIES FRE.DE FRESENIUS PSM.DE PROSIEBENSAT.1 MEDIA SE ADL.DE ADLER REAL ESTATE AG G1A.DE GEA PUM.DE PUMA SE ADS.DE ADIDAS AG G24.DE SCOUT24 AG QIA.DE QIAGEN N.V. ADV.DE ADVA OPTICAL NETWORKING SE GBF.DE BILFINGER SE RAA.DE RATIONAL AFX.DE CARL ZEISS MEDITEC AG - BR GFT.DE GFT TECHNOLOGIES SE RHK.DE RHOEN-KLINIKUM AG AIXA.DE AIXTRON SE GIL.DE DMG MORI RHM.DE RHEINMETALL AG ALV.DE ALLIANZ SE GLJ.DE GRENKE RIB1.DE RIB SOFTWARE SE AM3D.DE SLM SOLUTIONS GROUP AG GMM.DE GRAMMER AG RKET.DE ROCKET INTERNET SE AOX.DE ALSTRIA OFFICE REIT-AG GWI1.DE GERRY WEBER INTL AG S92.DE SMA SOLAR TECHNOLOGY AG ARL.DE AAREAL BANK AG GXI.DE GERRESHEIMER AG SAX.DE STROEER SE & CO KGAA BAS.DE BASF SE HAB.DE HAMBORNER REIT SAZ.DE STADA ARZNEIMITTEL AG BAYN.DE BAYER AG HBM.DE HORNBACH BAUMARKT AG SFQ.DE SAF HOLLAND S.A. BC8.DE BECHTLE AG HDD.DE HEIDELBERGER DRUCKMASCHINENSGL.DE SGL CARBON SE BDT.DE BERTRANDT AG HEI.DE HEIDELBERGCEMENT AG SHA.DE SCHAEFFLER AG BEI.DE BEIERSDORF AG HEN3.DE HENKEL AG & CO KGAA SIE.DE SIEMENS AG BIO4.DE BIOTEST AG HLAG.DE HAPAG-LLOYD AG SIX2.DE SIXT SE BMW.DE BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE AGHLE.DE HELLA KGAA HUECK & CO SKB.DE KOENIG & BAUER AG BNR.DE BRENNTAG AG HNR1.DE HANNOVER RUECK SE SPR.DE AXEL SPRINGER SE BOSS.DE HUGO BOSS -

European Technology, Media & Telecommunications Monitor

European Technology, Media & Telecommunications Monitor Market and Industry Update Fourth Quarter 2012 Piper Jaffray European TMT Team: Eric Sanschagrin Managing Director Head of European TMT [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8420 Stefan Zinzen Principal [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8418 Jessica Harneyford Associate [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8416 Peter Shin Analyst [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8444 Julie Wright Executive Assistant [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8427 TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS MONITOR Market and Industry Update Selected Piper Jaffray 2012 TMT Transactions 2 This report may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose without the written consent of Piper Jaffray. © 2013 Piper Jaffray Ltd. All rights reserved. TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS MONITOR Market and Industry Update Contents 1. Internet and Digital Media A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 2. Software and IT Services A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 3. Communications Technology And Hardware A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 4. Equity Capital Markets and M&A Update 3 This report may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose without the written consent of Piper Jaffray. © 2013 Piper Jaffray Ltd. All rights reserved. TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS -

Market Cap Close ADV 1598 67Th Pctl 745,214,477.91 $ 23.96

Market Cap Close ADV 1598 67th Pctl $ 745,214,477.91 $ 23.96 225,966.94 801 33rd Pctl $ 199,581,478.89 $ 10.09 53,054.83 2399 Ticker_ Listing_ Effective_ Revised Symbol Security_Name Exchange Date Mkt Cap Close ADV Stratum Stratum AAC AAC Holdings, Inc. N 20160906 M M M M-M-M M-M-M AAMC Altisource Asset Management Corp A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L AAN Aarons Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AAV Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd N 20160906 H L M H-L-M H-M-M AB Alliance Bernstein Holding L P N 20160906 H M M H-M-M H-M-M ABG Asbury Automotive Group Inc N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H ABM ABM Industries Inc. N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AC Associated Capital Group, Inc. N 20160906 H H L H-H-L H-H-L ACCO ACCO Brand Corp. N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H ACU Acme United A 20160906 L M L L-M-L L-M-L ACY AeroCentury Corp A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADK Adcare Health System A 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L ADPT Adeptus Health Inc. N 20160906 M H H M-H-H M-H-H AE Adams Res Energy Inc A 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L AEL American Equity Inv Life Hldg Co N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AF Astoria Financial Corporation N 20160906 H M H H-M-H H-M-H AGM Fed Agricul Mtg Clc Non Voting N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AGM A Fed Agricultural Mtg Cla Voting N 20160906 L H L L-H-L L-H-L AGRO Adecoagro S A N 20160906 H L H H-L-H H-L-H AGX Argan Inc N 20160906 M H M M-H-M M-H-M AHC A H Belo Corp N 20160906 L L L L-L-L L-L-L AHL ASPEN Insurance Holding Limited N 20160906 H H H H-H-H H-H-H AHS AMN Healthcare Services Inc. -

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding Sources for Entrepreneurs and Small Business

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding sources for entrepreneurs and small business. Introduction The Denver Office of Economic Development is pleased to release this fifth annual edition of the Denver Capital Matrix. This publication is designed as a tool to assist business owners and entrepreneurs with discovering the myriad of capital sources in and around the Mile High City. As a strategic initiative of the Denver Office of Economic Development’s JumpStart strategic plan, the Denver Capital Matrix provides a comprehensive directory of financing Definitions sources, from traditional bank lending, to venture capital firms, private Venture Capital – Venture capital is capital provided by investors to small businesses and start-up firms that demonstrate possible high- equity firms, angel investors, mezzanine sources and more. growth opportunities. Venture capital investments have a potential for considerable loss or profit and are generally designated for new and Small businesses provide the greatest opportunity for job creation speculative enterprises that seek to generate a return through a potential today. Yet, a lack of needed financing often prevents businesses from initial public offering or sale of the company. implementing expansion plans and adding payroll. Through this updated resource, we’re striving to help connect businesses to start-up Angel Investor – An angel investor is a high net worth individual active in and expansion capital so that they can thrive in Denver. venture financing, typically participating at an early stage of growth. Private Equity – Private equity is an individual or consortium of investors and funds that make investments directly into private companies or initiate buyouts of public companies. Private equity is ownership in private companies that is not listed or traded on public exchanges. -

Venture Capital Ecosystems: Digital Health in the United States

Venture Capital Ecosystems A Report on Digital Health in the United States CONTENTS SECTION ONE Introduction 03 SECTION TWO Industry Trends: US Digital Health Venture Ecosystem 05 SECTION THREE The Investment and Market Landscape 07 SECTION FOUR Methodology 24 MOSS ADAMS Venture Capital Ecosystems 02 SECTION ONE Introduction A watershed moment for the digital health industry, 2021 and 2021 revealed new paths forward for many companies and set the scene for a more favorable regulatory environment. As the COVID-19 pandemic’s ripple effects spread throughout the world, digital health technology became a necessary tool for meeting people’s health care needs. This proved to be a massive accelerant to both funding and innovation across the sector. In response, many digital health companies expanded, and deal values soared for early- and growth-stage investments. These developments introduced opportunities for digital health, but they also revealed new challenges, including increased competition, new operational demands, and a need for more judicious spend on capital. Below is a look at what the early- and growth-stage venture ecosystem looks like and steps your company can take to stay competitive in the changing environment. We hope you find this report useful. RICH CROGHAN National Practice Leader Life Sciences Practice MOSS ADAMS Venture Capital Ecosystems / Introduction 03 EARLY-STAGE VENTURE ECOSYSTEM AT A GLANCE Throughout the 2010s, venture In 2020, deal value spiked as A flood of capital into the digital investment rose steadily with invested venture capital (VC) hit health start-up environment scarcely a slowdown, in both $14.7 billion—a staggering surge enabled companies to stay count and aggregate value. -

Global / China Internet Trends

Global / China Internet Trends Shantou University / Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business / Hong Kong University November 7, 2005 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Outline • Attributes of Winning Companies • Global Internet • China Internet • Your Questions 2 Attributes of Winning Companies 3 Attributes of Winning Companies… 1. Large market opportunities - it is better to have 10%, and rising, market share of a $1 billion market than 100% of a $100M market 2. Good technology/service that offers a significant value/service proposition to its customers 3. Simple, direct mission and strong culture 4. Missionary (not mercenary), passionate, maniacally-focused founder(s) 5. Technology magnets (never underestimate the power of great engineers) 6. Great management team / board of directors / committed partners 7. Ability to lead change and embrace chaos 8. Leading/sustainable market position with first-mover advantage 9. Brand leadership, leading reach and market share 10.Global presence 4 …Attributes of Winning Companies 11. Insane customer focus and rapidly growing customer base 12. Stickiness and customer loyalty 13. Extensible product line(s) with focus on constant improvement and regeneration 14. Clear, broad distribution plans 15. Opportunity to increase customer “touch points” 16. Strong business and milestone momentum 17. Annuity-like business with sustainable operating leverage assisted by barriers-to-entry 18. High gross margins 19. Path to improving operating margins 20. Low-cost infrastructure and development efforts 5 Global Internet 6 Internet Data Points: Global… Global N. America = 23% of Internet users in 2005; was 66% in 1995 S. Korea Broadband penetration of 70%+ - No. 1 in world China More Internet users < age of 30 than anywhere 7 …Internet Data Points: Communications… Broadband 179MM global subscribers (+45% Y/Y, CQ2); 57MM in Asia; 45MM in N. -

Valuing Young Startups Is Unavoidably Difficult: Using (And Misusing) Deferred-Equity Instruments for Seed Investing

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 6-25-2020 Valuing Young Startups is Unavoidably Difficult: Using (and Misusing) Deferred-Equity Instruments for Seed Investing John L. Orcutt University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law, Concord, New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the Commercial Law Commons Recommended Citation John L. Orcutt, Valuing Young Startups is Unavoidably Difficult: Using (and Misusing) Deferred-Equity Instruments for Seed Investing, 55 Tulsa L.Rev. 469 (2020). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42208-tul_55-3 Sheet No. 58 Side A 05/15/2020 10:30:18 ORCUTT J - FINAL FOR PUBLISHER (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/2020 9:49 AM VALUING YOUNG STARTUPS IS UNAVOIDABLY DIFFICULT: USING (AND MISUSING) DEFERRED- EQUITY INSTRUMENTS FOR SEED INVESTING John L. Orcutt* I. ASTARTUP’S LIFE AND FUNDING CYCLES ............................................................... 474 II. VALUING YOUNG STARTUPS ................................................................................. -

Agenda Item 5B

Item 5b - Attachment 3, Page 1 of 45 SEMI - ANNUAL PERFORMANCE R EPORT California Public Employees’ Retirement System Private Equity Program Semi-Annual Report – June 30, 2017 MEKETA INVESTMENT GROUP B OSTON C HICAGO M IAMI P ORTLAND S AN D IEGO L ONDON M ASSACHUSETTS I LLINOIS F LORIDA O REGON C ALIFORNIA U N I T E D K INGDOM www.meketagroup.com Item 5b - Attachment 3, Page 2 of 45 California Public Employees’ Retirement System Private Equity Program Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Executive Summary 2. Private Equity Industry Review 3. Portfolio Overview 4. Program Performance 5. Program Activity 6. Appendix Vintage Year Statistics Glossary Prepared by Meketa Investment Group Page 2 of 45 Item 5b - Attachment 3, Page 3 of 45 California Public Employees’ Retirement System Private Equity Program Introduction Overview This report provides a review of CalPERS Private Equity Program as of June 30, 2017, and includes a review and outlook for the Private Equity industry. CalPERS began investing in the private equity asset class in 1990. CalPERS currently has an 8% interim target allocation to the private equity asset class. As of June 30, 2017, CalPERS had 298 investments in the Active Portfolio, and 319 investments in the Exited Portfolio1. The total value of the portfolio was $25.9 billion2, with total exposure (net asset value plus unfunded commitments) of $40.2 billion3. Executive Summary Portfolio The portfolio is diversified by strategy, with Buyouts representing the largest exposure at 66% of total Private Equity. Mega and Large buyout funds represent approximately 57% of CalPERS’ Buyouts exposure.