Vol. 12 No. 3 Pacific Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

253537449.Pdf

CD 105402 HAWAII ISLES OF ENCHANTMENT By CLIFFORD GESSLER Illustrated by E. H. SUYDAM D. APPLETON- CENTURY COMPANY INCORPORATED NEW YORK LONDON 1938 COPYRIGHT, 1937, BY JD. APPLETON-CENTURY COMPANY, INC. rights reserved. This book, or part** thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. Illustrations copyright, 937, by JE. HL Suydam Printed in the United States of America INTRODUCTION write of it or must RO away from Hawaii to is bewildered by KO away and return. A newcomer dazed the sharp impact of ONEits contradictions, by resident of long standing, on the thronging impressions. A so for that he other hand, tends to take the islands granted them to the stranger. may he handicapped in interpreting to be in a sense both One is fortunate, therefore, perhaps with the zeal kamaaina and malihini, neither exaggerating V Introduction *$: new convert the charm of those bright islands nor al~ dulled lotting it to be obscured with sensitivity by prolonged and not too daily familiarity. Time, not too long, distance, great, help to attain balance. The aim of this book is to write a national biography a character illumi- and to paint, in broad strokes, portrait, nated here and there by anecdote, of a country and a people that I have loved. Nor shall I tell here all I know about any one aspect of the islands. Not now, at any rate; this is not that kind of book. Scandal seldom reveals the true spirit of a community. The exception is not a reliable index, and controversies are like the shattered window which caused the policeman, after inspecting it without and within, to exclaim: "It's worse than I thought; it's broke on both sides!" Here again the long view is the clearest. -

Honolulu's Fourth Bishop Steered Diocese Through Contentious Times

HAWAII HAWAII HAWAII WORLD St. Patrick Seminary Class The long history of Tulua ordained a deacon Conflict, drought causing of 1977 celebrate 40th Honolulu’s cathedral has at Mass celebrating the largest humanitarian crisis anniversary on Maui seen many changes Assumption in more than 170 years Page 5 Page 6 Page 9 Page 10-11 HVOLUME 80,awaii NUMBER 17 CatholicFRIDAY, AUGUST 25, 2017 Herald$1 BISHOP FRANCIS XAVIER DILORENZO | 1942-2017 Honolulu’s fourth bishop steered diocese through contentious times Hawaii memorial Mass Bishop Larry Silva will celebrate a memorial Mass for Bishop Francis X. DiLorenzo at 6 p.m., Thursday, Sept. 7 at the Ca- thedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace. Funeral services for Bishop Francis X. DiLorenzo were scheduled at Richmond’s Cathedral of the Sacred Heart start- ing Aug. 24 with reception of the body, visitation and Vespers, fol- lowed by the bish- op lying in state through the night. Bishop Francis Funeral Mass is the X. DiLorenzo next day, Aug. 25, in his office at followed by en- the Honolulu tombment in the chancery in cathedral crypt. 1994. HCH file photo By Patrick Downes church for 49 years and a shepherd premacy, are sins against God and Hawaii Catholic Herald of the Diocese of Richmond for 13 profoundly wound the children of years,” said Msgr. Mark Richard God. I am grateful for the many ishop Francis X. DiLorenzo, Lane, Richmond’s vicar general. He people, including clergy and people who with a buoyant spirit said he was announcing the bishop’s of faith, who bravely stood against steered the Diocese of Ho- death “with great sadness.” hate, whether in prayer or in per- nolulu through contentious Bishop DiLorenzo was one of the son.” Btimes into the 21st century, died late first to call for peace during the cha- In a statement about his passing, Aug. -

P. Ángel Peña Oar San Damián De

P. ÁNGEL PEÑA O.A.R. SAN DAMIÁN DE VEUSTER APÓSTOL DE LOS LEPROSOS LIMA – PERÚ 1 SAN DAMIÁN DE VEUSTER, APÓSTOL DE LOS LEPROSOS Nihil Obstat Padre Ricardo Rebolleda Vicario Provincial del Perú Agustino Recoleto Imprimatur Mons. José Carmelo Martínez Obispo de Cajamarca (Perú) LIMA – PERÚ 2 ÍNDICE GENERAL INTRODUCCIÓN Su infancia. Su juventud. CAPÍTULO I: RELIGIOSO Y MISIONERO Al convento. Noviciado. Misionero. El viaje. Sacerdote. Puna. Kohala. La lepra en Hawai. CAPÍTULO II: EN MOLOKAI Molokai. Navidad de 1882. Fiesta de Pascua. Informe al Comité de Sanidad. Tratamientos de la lepra. Padre Damián leproso. El padre Damián ¿inmoral? El padre Damián ¿desobediente? Relato de Charles Warren Stoddard. Relato de Edward Clifford. Sus colaboradores en Molokai. Las religiosas. Así era él. Era un hombre feliz. Jesús Eucaristía. Otras devociones. Algunos carismas. Su muerte. CAPÍTULO III: SU GLORIFICACIÓN Después de su muerte. Su autoridad moral. Un gran santo. Sus restos. Canonización CONCLUSIÓN BIBLIOGRAFÍA 3 INTRODUCCIÓN La actividad misionera del padre Damián, el apóstol de los leprosos, se desarrolló en el archipiélago de las islas Hawai. Es un lugar llamado el paraíso del Pacífico o país de la eterna primavera con muchas palmeras gigantes, magnolias, naranjos, etc. El archipiélago de las islas Hawai o islas Sandwich comprende ocho islas mayores y una serie de islotes en un arco de 3.888 kilómetros en medio del océano Pacífico. Sus principales islas son Kauai, Ohau, donde está la capital Honolulú, Molokai, Lanai, Maui, Hawai, que es la más grande en extensión y da nombre al archipiélago. Hay un importante puerto, famoso desde la segunda guerra mundial, donde esta la base naval de Estados Unidos, que es Pearl Harbor. -

Rumors and the Language of Social Change in Early Nineteenth-Century Hawaii

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 12, No. 3 July 1989 RUMORS AND THE LANGUAGE OF SOCIAL CHANGE IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY HAWAII Char Miller Trinity University San Antonio, Texas In the first months of 1831, a pair of rumors ripped through Honolulu and Lahaina, the two major port towns of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and from there rippled outward to distant islands and districts. The first of these surfaced in February, and although elements of it would change in the ensuing months, it contained a consistent message: Liliha, wife of Boki, late governor of Oahu, was preparing a revolt against Kaahu- manu, who was serving as kuhina nui (regent) of the Islands until Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) came of age. The reports reached these two most powerful members of the Hawaiian royalty while they were conducting a tour of the windward islands, traveling with a host of high-ranking chiefs and American Protestant missionaries. Not only did they hear that Liliha would oppose the entourage’s return to Oahu but that the opposition she and her conspirators would offer would indeed be bloody; she was said to have declared that “there will be no peace until the heads of Kaahumanu and Mr. Bingham are taken off .”1 Hiram Bingham, one of the pioneer missionaries to the Islands and a close ally of Kaahumanu’s, was also the target of that spring’s second rumor. This one was not born of an islander-led revolt, but seemed to emerge from among disgruntled foreign residents in Honolulu; they at least helped to circulate it during the second week of April 1831. -

Father Jean Alexis Bachelot Letter MS.700

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x63pdr No online items Finding Aid to the Father Jean Alexis Bachelot Letter MS.700 Finding aid prepared by Holly Rose Larson Autry National Center, Braun Research Library 234 Museum Drive Los Angeles, CA, 90065-5030 323-221-2164 [email protected] 2012 November 9 Finding Aid to the Father Jean MS.700 1 Alexis Bachelot Letter MS.700 Title: Father Jean Alexis Bachelot Letter Identifier/Call Number: MS.700 Contributing Institution: Autry National Center, Braun Research Library Language of Material: English Physical Description: 0.1 linear feet(1 folder) Date: circa 1932 Abstract: This is a photostat of a letter of recommendation for Abel Stearns written in Spanish by Jean Alexis Bachelot, prefect apostolic of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), 1836 July 11. A translation and reference from David Burkenroad sent to Librarian Ruth Christensen in 1977 is also included in the collection. Language: English, Spanish. creator: Bachelot, Jean Alexis, Father Scope and Contents This is a photostat of a letter of recommendation for Abel Stearns written in Spanish by Jean Alexis Bachelot, prefect apostolic of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), 1836 July 11. A translation and reference from David Burkenroad sent to Librarian Ruth Christensen in 1977 is also included in the collection. Preferred citation Father Jean Alexis Bachelot Letter, circa 1932, Braun Research Library Collection, Autry National Center, Los Angeles; MS.700. Processing history Processed by Library staff after 1981. Finding aid completed by Holly Rose Larson, NHPRC Processing Archivist, 2012 November 9, made possible through grant funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commissions (NHPRC). -

Jennifer Fish-Kashay NATIVE, FOREIGNER, MISSIONARY, PRIEST

Fish-Kashay, Jennifer. “Native, Foreigner, Missionary, Priest: Western Imperialism and Religious Conflict in Early 19th-Century Hawaii,” Cercles 5 (2002) : 3-10 <www.cercles.com>. ©Cercles 2002. Toute reproduction, même partielle, par quelque procédé que ce soit, est interdite sans autorisation préalable (loi du 11 mars 1957, al. 1 de l’art. 40). ISSN : 1292-8968. Jennifer Fish-Kashay University of Arizona NATIVE, FOREIGNER, MISSIONARY, PRIEST Western Imperialism and Religious Conflict in Early 19th-Century Hawaii In the 1820s and 1830s, Hawaii’s native rulers found themselves caught between two competing groups of foreigners. On the one hand, American and European merchants who resided at the islands—some who had been there since the 1790s—hoped to continue to use their close relationship with the chiefs in order to advance their businesses, while enjoying the relaxed moral atmosphere of the isolated island chain. On the other hand, American Protest- ant missionaries, who had arrived at the Sandwich Islands in 1820, worked to both “civilize” and Christianize the native population. These two sets of di- vergent goals led the opposing groups of foreigners into constant conflict, leaving Hawaii’s chiefs, known as Ali’i Nui, to navigate a path for their people between the embattled foreigners. Under such circumstances, it proved in- evitable that the chiefs themselves would become involved directly in the con- flict. While missionaries, merchants, and Hawaiians clashed over a number of concerns, including prostitution and intemperance, the propagation of the Catholic religion at the Sandwich Islands served to focus the various strands of discourse on a single issue that brought the Sandwich Island rulers down the path of near destruction and drastic change. -

The French Perspective on the Laplace Affair

MARY ELLEN BIRKETT The French Perspective on the Laplace Affair THE PAGES THAT FOLLOW present for the first time English trans- lations of several French texts concerning the visit of Captain Cyrille- Pierre-Theodore Laplace and his fifty-two-gun frigate L'Artemise to Hawai'i in July 1839.1 Laplace was the first Frenchman to visit the Islands with specific instructions from Paris to enter into official dip- lomatic relations with the Hawaiian government. The French minis- ter of the navy, Ducampe de Rosamel, sent Laplace to Honolulu to make it unmistakably clear to the Hawaiian king and chiefs that if they wanted to maintain good relations with major international powers such as France, they must not take lightly promises made in treaties with those powers. Laplace believed that the treaty he presented to the Hawaiian king on July 12, 1839,2 secured freedom of worship for all inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands, thereby ending what the French government considered persecution of Roman Catholics in the archipelago. In addition, Captain Laplace persuaded King Kamehameha III to sign a convention on July 17, 1839, protecting the personal and commer- cial interests of Frenchmen in the Islands.3 This trade agreement also effectively repealed the ban on the sale of distilled liquors that the American Protestant clergy in Hawai'i had worked so hard to obtain. Not surprisingly, the American Protestant missionaries and their Mary Ellen Birkett is professor of French language and literature at Smith College, North- ampton, Massachusetts. She has been an annual contiributor to The Romantic Move- ment: A Selective and Critical Bibliography since 1979 and has published articles on the literary works of Rousseau, Lamartine, and Stendhal. -

Roman Catholic Church in the State of Hawaii Name NICK SAFKO Oba: Title Development Coordinator

House District 11 THE TWENTY-NINTH LEGISLATURE APPLICATION FOR GRANTS Log No: Senate District 6 CHAPTER 42F, HAWAII REVISED STATUTES Fer Legi•lature·s Use Only Type of Grant Request: r.8J GRANT REQUEST-OPERATING D GRANT REQUEST- CAPITAL "Grant" means an award of state funds by the legislature, by an appropriation to a specified recipient, to support the activities of the recipient and permit the community to benefit from those activities. "Recipient" means any organization or person receiving a grant. STATE DEPARTMENT OR AGENCY RELATED TO THIS llEQIJtST(LEAVEBLANKIFUNKNOWN): STATE PROGRAM l.D. NO. (LEA VE BLANK IF UNKNOWN): ------- 1, APPLICANT INFORMATION: 2. CONTACT PERSON FOR MATTERS INVOLVING nus APPLICATION: Legal Name of Requesting Organization or Individual: Roman Catholic Church in the State of Hawaii Name NICK SAFKO Oba: Title Development Coordinator. Hale Kau Kau Hale Kau Kau Program Phone # 808-875-8754 Street Address: 25 W. Lipoa St. Fax# 808-875-4674 Kihei, HI 96753 E-mail [email protected] Mailing Address: (same as above) 3. 1Yl't OF BUSINESS ENTITY: 6. DESCRIP'rlV.t TITLE OF APPLICANT'S REQUEST: r.8J NON PROFIT CORPORATION INCORPORATED IN HAWAII PROGRAM ENHANCEMENT FOR HOMEBOUND FOOD DELIVERY COMPONENT OF 0 FOR PROFIT CORPORATION INCORPORATED IN HAWAII THE HALE MU KAU l'ROORAM ANO STAFF RESTRUCTURING TO IMPROVE D LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY EFFECTIVENESS ANO SUSTAINABILITY. 0 SOLE PROPRIETORSHJP/INO!VIDUAL OOTHER 7. AMOUNT OF STATE FUNDS REQUESTED: 4. 5. FISCAL YEAR 2018; $100,000 8. STATUS OF SERVICE DESCRIBED IN TiflS REQUEST: 0 NEW SERVICE (PRESENTLY DOES NOT EXIST) SPECIFY THE AMOUNT BY SOURCES OF FUNDS AVAILABLE i'2l EXISTING SERVICE {PRESENTLY IN OPERATION) AT THE TIME OF TH!S REQUEST: STATE $0 FEDERAL $0 COUNTY $1.QQ.,QQQ PRIVATE/OTHER $347,320 . -

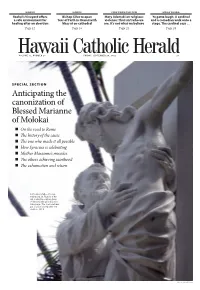

Anticipating the Canonization of Blessed Marianne of Molokai

HAWAII HAWAII VIEW FROM THE PEW MANA‘OLANA Rachel’s Vineyard offers Bishop Silva to open Mary Adamski on religious Ya gotta laugh: A cardinal a safe environment for Year of Faith in Hawaii with violence: That isn’t who we and a comedian walk onto a healing after an abortion Mass at co-cathedral are. It’s not what we believe stage. The cardinal says … Page 12 Page 16 Page 22 Page 28 HawaiiVOLUME 75, NUMBER 20 CatholicFRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2012 Herald$1 SPECIAL SECTION Anticipating the canonization of Blessed Marianne of Molokai On the road to Rome The history of the cause The one who made it all possible How Syracuse is celebrating Mother Marianne’s miracles The others achieving sainthood The exhumation and return A life-sized statue of Jesus embracing St. Francis of As- sisi marks the original grave of Blessed Marianne Cope in Kalaupapa. The memorial was put in place shortly after her death in 1918. HCH photo by Patrick Downes 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • SEPTEMBER 28, 2012 Hawaii Catholic Herald Newspaper of the Diocese of Honolulu Founded in 1936 Published every other Friday PUBLISHER Bishop Larry Silva (808) 585-3356 [email protected] EDITOR Patrick Downes (808) 585-3317 [email protected] REPORTER/PHOTOGRAPHER Darlene J.M. Dela Cruz (808) 585-3320 [email protected] ADVERTISING Shaina Caporoz (808) 585-3328 [email protected] CIRCULATION Donna Aquino (808) 585-3321 [email protected] HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD (ISSN-10453636) Periodical postage paid at Honolulu, Hawaii. Published every other week, 26 issues a year, by the Roman Catholic Church in the State of Hawaii, 1184 Bishop Street, Honolulu, HI 96813. -

Let the People the Governor’S Move to Secure a Same-Sex Marriage Bill Provokes Thousands to Fight Back by Patrick Downes in Four Long Days of Testimonies

HAWAII HAWAII HAWAII HAWAII Bishop Silva forms a It is a year of anniversaries Waialua’s Benedictine Visiting priests embody taskforce to promote the in the life and legacy priests incardinated the Hawaii-India- spirituality of stewardship of St. Marianne into the diocese Damien link Page 3 Page 7-10 Page 15 Page 17 HawaiiVOLUME 76, NUMBER 23 CatholicFRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2013 Herald$1 Let the people The governor’s move to secure a same-sex marriage bill provokes thousands to fight back By Patrick Downes in four long days of testimonies. woman, but needed the constitu- of Beretania Street fronting the Hawaii Catholic Herald More than 11,000 filled out post- tional amendment to back it up. Capitol, from Punchbowl Street to cards at Catholic churches which Richards Street, shoulder-to shoul- he special state legislative were sent to state lawmakers. THE RALLY der most of the way. session, called by Gov. Neil Their main message: “Let the According to Eva Andrade, ex- The bulk of the people, most Abercrombie on Oct. 28 to people decide!” ecutive director of Hawaii Family wearing dark blue as requested add Hawaii to the list of 14 It’s a call for a referendum to Forum, which organized the Oct. by organizers, were packed tight- TMainland states that have legal- change the state constitution that 28 Capitol rally with its legislative ly around the speakers’ stage set ized same-sex marriage, awakened harkens back to a similar grass- action arm Hawaii Family Advo- up in the Capitol rotunda. Others a giant of populist opposition. -

Hawaiian Historical Society

SIXTY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1955 SL SIXTY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1955 HONOLULU, HAWAII PUBLISHED, 1956 CONTENTS PAGE Officers and Committees for 1955 3 Officers and Committees for 1956 4 The History of Musical Development in Hawaii 5 by Emerson C. Smith Hawaiian Politics—(Documents) 1900 14 Captain Jules Dudoit, the First French Consul in the Hawaiian Islands, 1837-1867, and His Brig Schooner, the Clementine 21 By Leonce A. Jore. Translation by Dorothy Brown Aspinwall Minutes of the 64th Annual Meeting 37 Report of the President 38 Report of the Treasurer 39 Report of the Librarian 41 List of Members 44 The scope of the Hawaiian Historical Society as specified in its charter is "the collection, study, preservation and publication of all material pertaining to the history of Hawaii, Polynesia and the Pacific area." No part of this report may be reprinted unless credit is given to its author and to the Hawaiian Historical Society. The article on "The Musical Develop- ment in Hawaii," by Emerson C. Smith, is copyrighted by the author and may not be reprinted except with his express permission. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA THE ADVERTISER PUBLISHING CO., LTD., HONOLULU HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1955 President MEIRIC K. DUTTON Vice President CHARLES H. HUNTER Treasurer ROBERT R. MIDKIFF Corresponding Secretary and Librarian . MRS. WILLOWDEAN C. HANDY Recording Secretary BERNICE JUDD TRUSTEES FOR 1955-1956 TRUSTEES FOR 1956-1957 Kendall J. Fielder Janet E. Bell Charles H. Hunter Donald D.