Fire Management Today (68[3] Summer 2008), Visit Countries Around the World and Learn from International Experts About the Challenges of Firefighting Globally

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide PMS 210 April 2013 Wildland Fire Incident Management Field Guide April 2013 PMS 210 Sponsored for NWCG publication by the NWCG Operations and Workforce Development Committee. Comments regarding the content of this product should be directed to the Operations and Workforce Development Committee, contact and other information about this committee is located on the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Questions and comments may also be emailed to [email protected]. This product is available electronically from the NWCG Web site at http://www.nwcg.gov. Previous editions: this product replaces PMS 410-1, Fireline Handbook, NWCG Handbook 3, March 2004. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) has approved the contents of this product for the guidance of its member agencies and is not responsible for the interpretation or use of this information by anyone else. NWCG’s intent is to specifically identify all copyrighted content used in NWCG products. All other NWCG information is in the public domain. Use of public domain information, including copying, is permitted. Use of NWCG information within another document is permitted, if NWCG information is accurately credited to the NWCG. The NWCG logo may not be used except on NWCG-authorized information. “National Wildfire Coordinating Group,” “NWCG,” and the NWCG logo are trademarks of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names or trademarks in this product is for the information and convenience of the reader and does not constitute an endorsement by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group or its member agencies of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. -

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire

Forest Service Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center Wildland Fire Program 2016 Annual Report Weber Basin Job Corps: Above Average Performance In an Above Average Fire Season Brandon J. Everett, Job Corps Forest Area Fire Management Officer, Uinta-Wasatch–Cache National Forest-Weber Basin Job Corps Civilian Conservation Center The year 2016 was an above average season for the Uinta- Forest Service Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Job Corps Participating in nearly every fire on the forest, the Weber Basin Fire Program Job Corps Civilian Conservation Statistics Center (JCCCC) fire program assisted in finance, fire cache and camp support, structure 1,138 students red- preparation, suppression, moni- carded for firefighting toring and rehabilitation. and camp crews Weber Basin firefighters re- sponded to 63 incidents, spend- Weber Basin Job Corps students, accompanied by Salt Lake Ranger District Module Supervisor David 412 fire assignments ing 338 days on assignment. Inskeep, perform ignition operation on the Bear River RX burn on the Bear River Bird Refuge. October 2016. Photo by Standard Examiner. One hundred and twenty-four $7,515,675.36 salary majority of the season commit- The Weber Basin Job Corps fire camp crews worked 148 days paid to students on ted to the Weber Basin Hand- program continued its partner- on assignment. Altogether, fire crew. This crew is typically orga- ship with Wasatch Helitack, fire assignments qualified students worked a nized as a 20 person Firefighter detailing two students and two total of 63,301 hours on fire Type 2 (FFT2) IA crew staffed staff to that program. Another 3,385 student work assignments during the 2016 with administratively deter- student worked the entire sea- days fire season. -

Kneeland Helitack Base

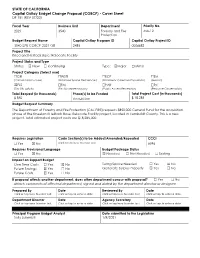

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Capital Outlay Budget Change Proposal (COBCP) - Cover Sheet DF-151 (REV 07/20) Fiscal Year Business Unit Department Priority No. 2021 3540 Forestry and Fire MA-12 Protection Budget Request Name Capital Outlay Program ID Capital Outlay Project ID 3540-078-COBCP-2021-GB 2485 0006682 Project Title Kneeland Helitack Base: Relocate Facility Project Status and Type Status: ☒ New ☐ Continuing Type: ☒Major ☐ Minor Project Category (Select one) ☐CRI ☐WSD ☐ECP ☐SM (Critical Infrastructure) (Workload Space Deficiencies) (Enrollment Caseload Population) (Seismic) ☒FLS ☐FM ☐PAR ☐RC (Fire Life Safety) (Facility Modernization) (Public Access Recreation) (Resource Conservation) Total Request (in thousands) Phase(s) to be Funded Total Project Cost (in thousands) $ 850 Acquisition $ 18,285 Budget Request Summary The Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) requests $850,000 General Fund for the acquisition phase of the Kneeland Helitack Base: Relocate Facility project, located in Humboldt County. This is a new project. Total estimated project costs are $18,285,000. Requires Legislation Code Section(s) to be Added/Amended/Repealed CCCI ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. 6596 Requires Provisional Language Budget Package Status ☐ Yes ☒ No ☒ Needed ☐ Not Needed ☐ Existing Impact on Support Budget One-Time Costs ☐ Yes ☒ No Swing Space Needed ☐ Yes ☒ No Future Savings ☒ Yes ☐ No Generate Surplus Property ☒ Yes ☐ No Future Costs ☒ Yes ☐ No If proposal affects another department, does other department concur with proposal? ☐ Yes ☐ No Attach comments of affected department, signed and dated by the department director or designee. Prepared By Date Reviewed By Date Click or tap here to enter text. -

Alphabetical Price List April 2020 SKU SKU Description Status Retail Whl

Alphabetical Price List April 2020 SKU SKU Description Status Retail Whl Break 1 Break 1 Break 2 Break 2 Break 3 Break 3 Break 4 Break 4 10003 10003-Emb NYLT A 4.99 3.29 12 2.99 48 2.79 0 0 0 0 100 100-Applique Embd FDL 4pk A 2.99 2.24 12 1.99 48 1.59 0 0 0 0 1013 1013-Giftcard TrailsEndPrgrm 013 N 13 11.05 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 101 101-Pin FDL Silvertone 5/8"@ A 3.99 2.99 24 2.79 0 0 0 0 0 0 10202 10202-Emb Ptrl Antelope A 2.49 1.79 12 1.69 300 1.29 0 0 0 0 10206 10206-Emb Ptrl Beaver A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10209 10209-Emb Ptrl Bobwhite A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10211 10211-Emb Ptrl Dragon A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10212 10212-Emb Ptrl Eagle A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10213 10213-Emb Ptrl Flaming Arrow A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10215 10215-Emb Ptrl Fox A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10221 10221-Emb Ptrl Lightning A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10223 10223-Emb Ptrl Owl A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10226 10226-Emb Ptrl Pheasant N 0.39 0.39 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1022 1022-Giftcard TrailsEndPrgrm 022 N 22 18.7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10230 10230-Emb Ptrl Rattlesnake A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10233 10233-Emb Ptrl Scorpion A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10234 10234-Emb Ptrl Shark A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10237 10237-Emb Ptrl Viking A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10239 10239-Emb Ptrl Wolf A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10240 10240-Emb Ptrl Blnk A 2.49 1.89 12 1.69 48 1.29 0 0 0 0 10302 10302-Emb Merit Camping A 2.79 2.39 12 2.19 144 1.89 0 0 0 0 10303 10303-Emb -

FOO FIGHTERS to PERFORM in BRIDGEPORT AS PART of 25Th 26Th ANNIVERSARY TOUR

FOO FIGHTERS TO PERFORM IN BRIDGEPORT AS PART OF 25th 26th ANNIVERSARY TOUR HARTFORD HEALTHCARE AMPHITHEATER FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 Tickets On Sale on Friday, August 13 @ 10 AM Eastern Photo Credit: Danny Clinch Fresh off a series of dates including the return of rock n roll to Madison Square Garden and a triumphant Lollapalooza headline set, Foo Fighters will perform in Bridgeport’s new boutique amphitheater – the Hartford HealthCare Amphitheater on Friday, September 17. Tickets will go on sale on Friday, August 13 at 10 a.m. The Foo Fighters are celebrating their 25th 26th anniversary and the February release of Medicine at Midnight (Roswell/RCA). In Bridgeport, the FF faithful will finally have the chance to sing along to “Shame Shame,” “No Son of Mine,” “Making A Fire,” and more from the album that’s been hailed as “brighter and more optimistic than anything they’ve ever done" (ROLLING STONE)” and "one of Foo Fighters’ best albums of this century” (WALL STREET JOURNAL). This show will require fans to provide either proof of COVID-19 vaccination or negative test result within 48 hours for entry. This extra step is being taken out of an abundance of caution as it is the best way to protect crew and fans. More information can be found at https://hartfordhealthcareamp.com FF fans are advised to keep a watchful eye on foofighters.com and the band’s socials for more shows to be announced. Citi is the official presale credit card of the Foo Fighters Tour. As such, Citi cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, August 10 at 12 p.m. -

IJA Enewsletter Editor Don Lewis (Email: [email protected]) Renew at Http

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERSʼ ASSOCIATION December 2011 IJA eNewsletter editor Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http:www.juggle.org/renew IJA eNewsletter Contents: Happy Holidays IJA eZine ! Teaching the Cascade Recycling - Build Green Clubs Stagecraft Corner 2011 Festival Video AMS System Update Rain Ending... an 8 year run 7 Doigts on Time Top 10 List Rola Bola 2 Feeding the Inner Juggler Turbo Fest 2012 Regional Festivals Best Catches Juggling Festivals: Waidhofen, Austria Quebec, QC, Canada North Goa, India Seattle, WA Madison, WI Sydney, Australia Atlanta, GA The holiday cartoon above originally appeared in Heerien, Netherlands the November 1979 IJA newsletter. Regardless St. Paul, MN of what holiday youʼre celebrating this season, Austin, TX have a happy and safe one. Don Lewis, Editor Bath, UK Arcata, CA Bali, Indonesia Southend on Sea, UK Winston-Salem, NC IJA Festival 2012 Marion, IN Winston-Salem, NC July 16 - 22, 2012 Save the dates! WWW.JUGGLE.ORG Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERSʼ ASSOCIATION December 2011 eZine ? Coming January 1, 2012 http://ezine.juggle.org Celebrate the New Year with the IJAʼs new eZine! WWW.JUGGLE.ORG Page 2 THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERSʼ ASSOCIATION December 2011 Teaching the Cascade, by Don Lewis Hereʼs the scenario: You go to a seasonal party at a stem from anxiety - trying to go too fast. Just stand in friend or relativeʼs place. Perhaps you only see them front and do two throws as slow as you can. Get them to once a year. Someone will have received a set of juggling copy you. This rarely takes more than a couple of balls as a gift, which are sitting unused because they keep minutes. -

Town Report 05-06 Text

Town of Annual Report IN MEMORY OF NANCY O. WAY In memory of Nancy O. Way, Deputy First Selectman who passed away Thursday, July 27, 2006 after a brief battle with cancer. Nancy was a valuable member of the Board of Selectmen for over 10 years, serving as Deputy First Selectman for over 4 years. She also served on various subcommittees of the Board of Selectmen. Prior to serving on the the Board of Selectmen, she was a member of the Board of Education. Nancy volunteered on many civic and farm organizations over the years and was an active member of the Ellington Historical Society and the Republican Town Committee. In the early 1990’s she had been involved and very active in several local groups that challenged the proposed nuclear waste sites for Ellington. She had a passion for the Town of Ellington and its history. She will be remembered fondly as a dedicated and caring citizen, elected official and friend. 2006 Wall of Honor Recipient The Board of Selectmen selected Everett C. Paluska as the 2006 Wall of Honor Recipient in recognition of his many years of services and outstanding contributions to the Town of Ellington. EVERETT C. PALUSKA Everett served as Tax Collector, First Selectman, Republican 1294-2001 Town Chairman, Prosecuting Grand Juror of the former Ellington Justice Court and Probation Officer. Everett was an active Many Years of Service & member of the Ellington Cemetary Association, serving as Outstanding Contributions to the Town President for 15 years. Everett also devoted countless hours to the Ellington Congregational Church and demonstrated extraordinary dedication to his family and community. -

Incident Management Organization Succession Planning Stakeholder Feedback

Incident Management United States Department Organization Succession Planning of Agriculture Forest Service Stakeholder Feedback Rocky Mountain Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-297 Anne E. Black January 2013 Black, Anne E. 2013. Incident Management Organization succession planning stakeholder feedback. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-297 Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 322 p. ABSTRACT This report presents complete results of a 2011 stakeholder feedback effort conducted for the National Wildfire Coordination Group (NWCG) Executive Board concerning how best to organize and manage national wildland fire Incident Management Teams in the future to meet the needs of the public, agencies, fire service and Team members. Feedback was collected from 858 survey respondents and 57 email comments. In order to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the affected community and issues of relevance for implementation, the report includes: a final overview, complete narrative and survey responses, relevant statistical results and interpretation. Keywords: Incident Management, wildland fire, National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), IMT succession planning AUTHOR Anne E. Black, is a Social Science Analyst with the Human Factors and Risk Management RD&A, part of the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Stationed in Missoula, Montana, she focuses on understanding the theory and practice of high performance, risk management and organizational learning at team and organizational levels, particularly in the wildland fire community. She received her PhD from the University of Idaho in Forest Resources with an emphasis in landscape ecology, a Masters in Environmental Studies from Yale Scholl of Forestry and Environmental Studies, and a Bachelor’s of Science in Resource Conservation from the University of Montana. -

Flying Disc Illustrated V1n4 Summer84contributor

‘“j£“j“‘ 11111‘T‘ CHAMPION DISCS INC. KEH PERFORMANCE DEPENDABLE UNBREAKABLE EASY TO THRGN P. D.G.A. APPROVED These Terms combined cdn only describe one compony’s flying discs, iNNOVA””— CHAMPION DISCS INC. We are The folkswho brought you The AERO ond The AV|AR”‘flying discs. We hope you enjoy them. TM INNOVA"”—CHAMP|ONDISCS, INC. FILE?HN@ 1IDH@@ flll IIPHIITI FDI has decided to expand the scope of its coverage. As a result of strong support we have received from around the world, we have so much material to print, that it has become incumbent upon us to increase the number of pages in our issue. Many of our readers have also PAGE'1 PAGE14 PAGE11 submitted pictures for publi- cation. Unfortunately, most of CONTENTS: 1984 the pictures that we receive are in color. Although we hope to SWEDEN: OVERSEAS UPDATE 4 eventually print in color, our SANTA BARBARA CLASSIC 4 present finances dictate that we LETTERS 6 print in black and white at least FRANCE: INTERNATIONAL TOURNAMENT 6 for the time being. l984 U.s. OPEN: LA MIRADA 7 In addition, in upcoming FOOTBAG: SACK SECTION 10 issues we will be including a SENIOR WORLDS 10 special footbag department. As a INTERVIEW: DAN RODDICK l2 result of having experienced PDGA 13 first hand the Hacky Sack and ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONALS: BOULDER 10 Frisbee Festival held here in San ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONALS: FT. COLLINS 12 Diego On July 7th, the unique INSTRUCTIONAL CORNER: BODY ROLLS 14 bond between footbag and disc has FPA WORLDS: MINNEAPOLIS 17 become increasingly apparent. -

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ziolkowski, Jan M. The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Volume 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. Published Version https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/822 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40880864 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR AND PEACE, SEX AND VIOLENCE JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 6 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. -

Oregon Department of Forestry

STATE OF OREGON POSITION DESCRIPTION Position Revised Date: 04/17/2019 This position is: Classified Agency: Oregon Department of Forestry Unclassified Executive Service Facility: Central Oregon District, John Day Unit Mgmt Svc - Supervisory Mgmt Svc - Managerial New Revised Mgmt Svc - Confidential SECTION 1. POSITION INFORMATION a. Classification Title: Wildland Fire Suppression Specialist b. Classification No: 8255 c. Effective Date: 6/03/2019 d. Position No: e. Working Title: Firefighter f. Agency No: 49999 g. Section Title: Protection h. Employee Name: i. Work Location (City-County): John Day Grant County j. Supervisor Name (optional): k. Position: Permanent Seasonal Limited duration Academic Year Full Time Part Time Intermittent Job Share l. FLSA: Exempt If Exempt: Executive m. Eligible for Overtime: Yes Non-Exempt Professional No Administrative SECTION 2. PROGRAM AND POSITION INFORMATION a. Describe the program in which this position exists. Include program purpose, who’s affected, size, and scope. Include relationship to agency mission. This position exists within the Protection from Fire Program, which protects 1.6 million acres of Federal, State, county, municipal, and private lands in Grant, Harney, Morrow, Wheeler, and Gilliam Counties. Program objectives are to minimize fire damage and acres burned, commensurate with the 10-year average. Activities are coordinated with other agencies and industry to avoid duplication and waste of resources whenever possible. This position is directly responsible to the Wildland Fire Supervisor for helping to achieve District, Area, and Department-wide goals and objectives at the unit level of operation. b. Describe the primary purpose of this position, and how it functions within this program. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents .