Unit (1-6) Editor : Prof. Tapan Biswal SCHO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of UK Electoral Systems

Patrick Dunleavy and Helen Margetts The impact of UK electoral systems Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Dunleavy, Patrick and Margetts, Helen (2005) The impact of UK electoral systems. Parliamentary affairs, 58 (4). pp. 854-870. DOI: 10.1093/pa/gsi068 © 2005 Oxford University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/3083/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2008 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Forthcoming in Parliamentary Affairs, September 2005 THE IMPACT OF THE UK’S ELECTORAL SYSTEMS* Patrick Dunleavy and Helen Margetts In the immediate aftermath of the general election the Independent ran a whole-page headline illustrated with contrasting graphics showing ‘What we voted for’ and ‘What we got’, followed up by ‘…and why it’s time for change’.1 The paper launched a petition calling for a shift to a system that is fairer and more proportional, which in rapid time attracted tens of thousands of signatories, initially at a rate of more than 500 people a day. -

Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 7 Tab Number: 5 Document Title: Macedonia Final Report, May 2000-March 2002 Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Macedonia lFES ID: ROl727 I I I I I I I I I IFES MISSION STATEMENT I I The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about I democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov I ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi I ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter I disciplinary in its approach. I I I I MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK Macedonia FINAL REPORT May 2000- March 2002 USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT No. EE-A-00-97-00034-00 Submitted to the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT by the INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTION SYSTEMS I I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTNE SUMMARY I I. PROGRAMMATIC ACTNITIES ............................................................................................. 1 A. 2000 Pre Election Technical Assessment 1 I. Background ................................................................................. 1 I 2. Objectives ................................................................................... 1 3. Scope of Mission .........................................................................2 -

Elections REFORM September 2015

TOPIC EXPLORATION PACK GCSE Theme: Elections REFORM September 2015 GCSE (9–1) Citizenship Studies Oxford Cambridge and RSA We will inform centres about any changes to the specification. We will also publish changes on our website. The latest version of our specification will always be the one on our website (www.ocr.org.uk) and this may differ from printed versions. Copyright © 2015 OCR. All rights reserved. Copyright OCR retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, registered centres for OCR are permitted to copy material from this specification booklet for their own internal use. Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England. Registered company number 3484466. Registered office: 1 Hills Road Cambridge CB1 2EU OCR is an exempt charity. This resource is an exemplar of the types of materials that will be provided to assist in the teaching of the new qualifications being developed for first teaching in 2016. It can be used to teach existing qualifications but may be updated in the future to reflect changes in the new qualifications. Please check the OCR website for updates and additional resources being released. We would welcome your feedback so please get in touch. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Activity 1 ........................................................................................................................................ -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Lessons on Voting Reform from Britian's First Pr Elections

WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW: LESSONS ON VOTING REFORM FROM BRITIAN'S FIRST PR ELECTIONS by Philip Cowley, University of Hull John Curtice, Strathclyde UniversityICREST Stephen Lochore, University of Hull Ben Seyd, The Constitution Unit April 2001 WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW: LESSONS ON VOTING REFORM FROM BRITIAN'S FIRST PR ELECTIONS Published by The Constitution Unit School of Public Policy UCL (University College London) 29/30 Tavistock Square London WClH 9QU Tel: 020 7679 4977 Fax: 020 7679 4978 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/ 0 The Constitution Unit. UCL 200 1 This report is sold subject ot the condition that is shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. First published April 2001 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ..................................................................................4 Voters' attitudes to the new electoral systems ...........................................................4 Voters' behaviour under new electoral systems ......................................................... 4 Once elected .... The effect of PR on the Scottish Parliament in Practice ..................5 Voter Attitudes to the New Electoral Systems ............................................6 -

Electoral Reform Three Case Studies

Electoral reform Three Case Studies • Japan • New Zealand • Italy MMM vs. MMP • MMM vs. MMP… what’s the difference? • In both, seats are allocated at the district and national levels • MMP is a hybrid system – District-level winners – National PR is compensatory • MMM is a parallel voting system – List seats allocated proportionally… – …But not linked to district-level winners • What are plusses and minuses? Why do political scientists like MMP better? Electoral reform: Japan (1996) • BEFORE: SNTV – What kinds of problems did SNTV bring? • AFTER: MMM • WHY: LDP wanted reform. Electoral reform: Japan • In 1970, PM Satō asked a party committee to propose an electoral system based on single-seat districts to “produce party-centered, policy-centered campaigns.” Effect of electoral reform: Indices Year D (LSq) N(v) N(s) S 6.20 3.82 3.08 12.28 3.66 2.60 Period averages in red (overall in post-reform period through 2009) 6 2009 Election Results Electoral reform: New Zealand (1996) • BEFORE: FPTP • AFTER: MMP • WHY: It’s complicated! New Zealand: Problems with the old system 9 An electoral system working “too well” New Zealand is classic case of an electoral system producing too much majoritarianism New Zealand Electoral Statistics, 1978-1993 Party 1978 1981 1984 1987 1990 1993 Labour Vote % 40.4 39.0 43.0 48.0 35.1 34.7 Seat % 43.5 46.7 60.0 58.8 29.9 45.5 National Vote % 39.8 38.8 35.9 44.0 47.8 35.0 Seat % 55.4 51.1 37.9 41.2 69.1 50.5 Social Credit Vote % 16.1 20.7 7.6 - - - Seat % 1.1 2.2 2.1 - - - NZ Party Vote % - - 12.3 0.3 - - Seat % - - 0.0 0.0 - - *Alliance Vote % - - - - 14.3 18.2 Seat % - - - - 1.0 2.0 NZ First Vote % - - - - - 8.4 Seat % - - - - - 0.0 *The Alliance consists of several minor third parties, including Green, New Labour, Democrat and Mana Motuhake. -

Strengthening New Brunswick's Democracy

Strengthening New Brunswick’s Democracy Select Committee Discussion Paper on Electoral Reform July 2016 Strengthening New Brunswick’s Democracy Discussion Paper July 2016 Published by: Government of New Brunswick PO Box 6000 Fredericton, New Brunswick E3B 5H1 Canada Printed in New Brunswick ISBN 978-1- 4605-1033-9 (Print Bilingual) ISBN 978-1- 4605-1034-6 (PDF English) ISBN 978-1- 4605-1035-3 (PDF French) 10744 Table of Contents Select Committee on Electoral Reform 1 Message from the Government House Leader 2 How to use this discussion paper 3 Part 1: Introduction 4 Part 2: Making a more effective Legislature 8 Chapter 1: Eliminating barriers to entering politics for underrepresented groups 8 Chapter 2: Investigating means to improve participation in democracy 12 Internet voting 18 Part 3: Other electoral reform matters 20 Chapter 1: Election dates 20 Chapter 2: Election financing 21 Part 4: Conclusion 24 Part 5 : Appendices 25 Appendix A - Families of electoral systems 25 Appendix B - Voting systems 26 Appendix C - First-Past-the-Post 31 Appendix D - Preferential ballot voting: How does it work? 32 Appendix E- Election dates in New Brunswick 34 Appendix F - Fixed election dates: jurisdictional scan 36 Appendix G- Limits and expenses: Adjustments for inflation 37 Appendix H - Contributions: Limits and allowable sources jurisdictional scan 38 Appendix I - Mandate of the Parliamentary Special Committee on Electoral Reform 41 Appendix J - Glossary 42 Appendix K - Additional reading 45 Select Committee on Electoral Reform The Legislature’s Select Committee on Electoral Reform The committee is to table its final report at the Legislative is being established to examine democratic reform in the Assembly in January 2017. -

Should Your Vote Always Count? (Changing the Voting System)

Should your vote always count? (Changing the voting system) Many attempts at producing a voting system that makes every vote count and prevent a minority of the electorate electing a governing body (especially a National Government). Voting systems 1. Plurality voting system/relative majority (First past the post /UK system) 2. Majority voting system (Requires more than half the votes cast/used by some institutions to elect executives/leaders) 3. Single Transferable Vote a. On Election Day, voters number a list of candidates. Their favourite as number one, their second favourite number two, and so on. Voters can put numbers next to as many or as few candidates as they like. Parties will often stand more than one candidate in each area. b. The numbers tell the people counting to move your vote if your favourite candidate has enough votes already or stands no chance of winning. 4. Alternative Vote a. The voter puts a number by each candidate, with a one for their favourite, two for their second favourite and so on. They can put numbers on as many or as few as they wish. b. If more than half the voters have the same favourite candidate, that person becomes the MP. If nobody gets half, the numbers provide instructions for what happens next. c. The counters remove whoever came last and look at the ballot papers with that candidate as their favourite. Rather than throwing away these votes, they move each vote to the voter’s second favourite candidate. This process repeated until one candidate has half of the votes and becomes the MP. -

First Past the Post (FPTP), Also Known As Simple Majority Voting Or Plurality Voting

First Past the Post First Past The Post (FPTP), also known as Simple majority voting or Plurality voting How does First Past The Post work? Under First Past The Post (FPTP) voting takes place in single-member constituencies. Voters put a cross in a box next to their favoured candidate and the candidate with the most votes in the constituency wins. All other votes count for nothing. We believe FPTP is the very worst system for electing a representative government. Where is First Past The Post used? FPTP is the second most widely used voting system in the world, after Party List-PR. In crude terms, it is used in places that are, or once were, British colonies. Of the many countries that use First Past The Post , the most commonly cited are the UK to elect members of the House of Commons, both chambers of the US Congress, and the lower houses in India and Canada. First Past The Post used to be even more widespread, but many countries that used to use it have adopted other systems. Find out more about reform overseas... Pros and cons of First Past The Post The case for The arguments against It's simple to understand and thus Representatives can get elected on tiny amounts of public support as it doesn't cost much to administer. does not matter by how much they win, only that they get more votes than other candidates. It doesn't take very long to count It encourages tactical voting, as voters vote not for the candidate they all the votes and work out who's most prefer, but against the candidate they most dislike. -

Gerrymandering and Fair Districting in Parallel Voting Systems Arxiv

Gerrymandering and fair districting in parallel voting systems Igor Mandric1, Igor Roşca2, and Radu Buzatu3 1Department of Computer Science, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chişinˇau,Moldova 3Department of Mathematics, Moldova State University, Chişinˇau, Moldova Abstract Switching from one electoral system to another one is frequently criticized by the opposition and is viewed as a means for the ruling party to stay in power. In particular, when the new electoral system is a parallel voting (or a single-member district) system, the ruling party is usually suspected of a bi- ased way of partitioning the state into electoral districts such that based on a priori knowledge it has more chances to win in a maximum possible number of districts. In this paper, we propose a new methodology for deciding whether a particular party benefits from a given districting map under a parallel voting system. As a part of our methodology, we formulate and solve several gerry- mandering problems. We showcased the application of our approach to the Moldovan parliamentary elections of 2019. Our results suggest that contrary to the arguments of previous studies, there is no clear evidence to consider that the districting map used in those elections was unfair. 1 Introduction arXiv:2002.06849v1 [physics.soc-ph] 17 Feb 2020 Political (re-)districting represents the task of partitioning a geographic area (e.g., a state or an administrative unit) into a given number of electoral districts subject to a predefined set of requirements [1]. Frequently, the requirements are formulated with respect to demographic and/or geographic peculiarities of the area [2]. -

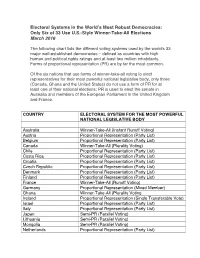

Electoral Systems in the World's Most Robust Democracies

Electoral Systems in the World’s Most Robust Democracies: Only Six of 33 Use U.S.-Style Winner-Take-All Elections March 2016 The following chart lists the different voting systems used by the world's 33 major well-established democracies – defined as countries with high human and political rights ratings and at least two million inhabitants. Forms of proportional representation (PR) are by far the most common. Of the six nations that use forms of winner-take-all voting to elect representatives for their most powerful national legislative body, only three (Canada, Ghana and the United States) do not use a form of PR for at least one of their national elections; PR is used to elect the senate in Australia and members of the European Parliament in the United Kingdom and France. COUNTRY ELECTORAL SYSTEM FOR THE MOST POWERFUL NATIONAL LEGISLATIVE BODY Australia Winner-Take-All (Instant Runoff Voting) Austria Proportional Representation (Party List) Belgium Proportional Representation (Party List) Canada Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting) Chile Proportional Representation (Party List) Costa Rica Proportional Representation (Party List) Croatia Proportional Representation (Party List) Czech Republic Proportional Representation (Party List) Denmark Proportional Representation (Party List) Finland Proportional Representation (Party List) France Winner-Take-All (Runoff Voting) Germany Proportional Representation (Mixed Member) Ghana Winner-Take-All (Plurality Voting Ireland Proportional Representation (Single Transferable Vote) Israel Proportional -

Revised Comparative Table on Proportional Electoral

Strasbourg, 30 April 2015 CDL-PI(2015)006 Study No. 764/2014 Or. Engl./fr. EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) REVISED COMPARATIVE TABLE1 ON PROPORTIONAL ELECTORAL SYSTEMS: THE ALLOCATION OF SEATS INSIDE THE LISTS (OPEN/CLOSED LISTS) 1 The legal provisions contained in this table refer to lower chambers, unless otherwise indicated. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera pas distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. www.venice.coe.int CDL-PI(2015)006 - 2 - Proportional systems, Proportional systems: Electoral systems, Proportional systems, methods of allocation of Country Legal basis System of representation closed or open party main relevant provision(s) methods of allocation of seats seats list system? inside the lists Constitution Proportional system: Constitution Largest remainder Closed Party List No preference Article 64 All the 140 members of the Article 64 (amended by Law no. D’Hondt, then Sainte-Laguë system Not indicated in the law but Parliament are elected through 9904, dated 21.04.2008) formulas No preference implicitly clear that there is Electoral Code a proportional representation 1. The Assembly consists of 140 no preference. (approved by Law system within constituencies deputies, elected by a proportional See the separate document for no. 10 019, dated 29 corresponding to the 12 system with multi-member electoral Articles 162-163. December 2008, administrative regions. zones. and amended by The threshold to win 2. A multi-member electoral zone According to the stipulations in Law no. 74/2012, parliamentary representation is coincides with the administrative Articles 162 and 163 of the Electoral dated 19 July 2012) 3 percent for political parties division of one of the levels of Code, the number of seats is Articles 162 & 163 and 5 per cent for pre-election administrative-territorial calculated for each of the coalitions coalitions.