Nose Hill Artifacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

152 +15 33 17Th Avenue 35 Accès 120 Accessoires 46, 47, 63, 76

152 index +15 33 Aussie Rules Foodhouse & Piano Bar 74 17th Avenue 35 Banff Paddock Pub 99 Bookers 60 A Broken City Social Club 41 Canmore Hotel 117 Accès 120 Commonwealth 41 Accessoires 46, 47, 63, 76 Cowboy’s 73 Aero Space Museum of Calgary 77 Craft Beer Market 42 Afrikadey 148 Drum and Monkey 42 Alberta Hotel 33 Elk & Oarsman 99 Glacier Saloon 117 Alberta’s Dream 32 HiFi Club 42 Alimentation 44, 47, 63, 76 Hoodoo Lounge 99 Ambassades 136 James Joyce 42 Argent 137 Kensington Pub 61 Art Gallery of Calgary 33 Lobby Lounge 74 Lounge at Bumper’s Beef House Articles de plein air 102 Restaurant 100 Auberges de jeunesse 123 Ming 43 Aylmer Lookout Viewpoint 114 Molly Malone’s 61 National Beer Hall 43 B Oak Tree Tavern 61 Banff 91 Ranchman’s 73 Raw Bar by Duncan Ly 43 Banff Gondola 86 Republik 43 Banff Mountain Film Festival 149 Rose & Crown 100 Banff Park Museum 94 Rundle Lounge 100 Banff Springs Hotel (Banff) 91 Ship & Anchor Pub 43 Banff Summer Arts Festival 148 St. James Gate 100 The Grizzly Paw Brewing Company 117 Banff Upper Hot Springs (Banff) 87 Wild Bill’s Legendary Saloon 100 Bankers Hall 33 Wine Bar Kensington 61 Bankhead Interpretive Trail 113 Wine-OHs Cellar 43 Banques 138 Bijoux 47 Barrier Lake Visitor Information Bloody Caesar 138 Centre 112 Bobsleigh 81 Bars et boîtes de nuit Boundary Ranch 112 Atlantic Trap And Gill 73 Bow Habitat Station 56 http://www.guidesulysse.com/catalogue/FicheProduit.aspx?isbn=9782894644201 153 Bowness Park 81 Déplacements 132 Bow River Falls 91 Devonian Gardens 34 Bow, The 32 Bow Valley Parkway 87 E -

Learning with Wetlands at the Sam Livingston Fish Hatchery: a Marriage of Mind and Nature

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 Learning with wetlands at the Sam Livingston fish hatchery: A marriage of mind and nature Grieef, Patricia Lynn Grieef, P. L. (1999). Learning with wetlands at the Sam Livingston fish hatchery: A marriage of mind and nature (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/12963 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25035 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca The University of Calgary Leurnhg with wetiads at the Sam Livingston Fish Hatchery: A Marriage of Mind and Nature by Patricia L. Grieef A Master's Degree Project submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Design in partial hlfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Design (Environmental Science) Calgary, Alberta September, 1999 O Patricia L. Grieef, 1999 National Library BibliotWque nationale 1*1 .,&"a& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nn, Wellington OttawaON KlAW OCtewaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Archaeology in Alberta 1978

ARCHAEOLOGY IN ALBERTA, 1978 Compiled by J.M. Hillerud Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper No. 14 ~~.... Prepared by: Published by: Archaeological Survey Alberta Culture of Alberta Historical Resources Division OCCASIONAL PAPERS Papers for publication in this series of monographs are produced by or for the four branches of the Historical Resources Division of Alberta Culture: the Provincial Archives of Alberta, the Provincial Museum of Alberta, the Historic Sites Service and the Archaeological Survey of Alberta. Those persons or institutions interested in particular subject sub-series may obtain publication lists from the appropriate branches, and may purchase copies of the publications from the following address: Alberta Culture The Bookshop Provincial Museum of Alberta 12845 - 102 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5N OM6 Phone (403) 452-2150 Objectives These Occasional Papers are designed to permit the rapid dissemination of information resulting from Historical Resources' programmes. They are intended primarily for interested specialists, rather than as popular publications for general readers. In the interests of making information available quickly to these specialists, normal production procedures have been abbreviated. i ABSTRACT In 1978, the Archaeological Survey of Alberta initiated and adminis tered a number of archaeological field and laboratory investigations dealing with a variety of archaeological problems in Alberta. The ma jority of these investigations were supported by Alberta Culture. Summary reports on 21 of these projects are presented herein. An additional four "shorter contributions" present syntheses of data, and the conclusions derived from them, on selected subjects of archaeo logical interest. The reports included in this volume emphasize those investigations which have produced new contributions to the body of archaeological knowledge in the province and progress reports of con tinuing programmes of investigations. -

2009 PES General Meeting 2630 July 2009

2009 PES General Meeting 2630 July 2009 Calgary Telus Convention Centre Calgary (Alberta) Canada Introduction The Power & Energy Society is pleased to announce that its 2009 General Meeting is scheduled for July 26‐30, 2009 at the Calgary Telus Convention Centre in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The conference, with its theme “Investment in Workforce and Innovation for Power Systems”, will provide an international forum to address policy, infrastructure and workforce issues. We invite our colleagues from around the world to join us in Calgary for this memorable industry meeting. During the meeting you will have the opportunity to participate in many high‐quality technical sessions and tours, committee meetings, networking opportunities and more. There will also be special student events and entertaining companion activities planned throughout the week. Schedule Overview Student Program Calgary Welcome Reception Weather Companion/Leisure Activities Currency PLAINTALK: Power Systems Courses Tourism Opportunities for Non‐Power Engineers Conference Location and Hotels Transportation From the Airport Registration Customs/ Entry into Canada Registration Categories PES Members Meeting REGISTRATION FEES (all fees stated in US Dollars) Plenary Session Attendee Breakfasts Awards Presenter Breakfasts Technical Program Conference Proceedings Poster Session Paper Market Committee Meetings Audio‐Visual Presentation Needs Tutorials Presenters Preparation Room Technical Tours Message Center Calgary Energy Center Professional Development Hours TransAlta Hydro Facilities on Bow Attire River PES and IEEE Booths and Tables Corporate Support Opportunities Schedule Overview Note: A limited number of sessions and events (in particular, some committee meeting) may fall outside this schedule. Day Time Event/Sessions Sunday All Day Registration/Information; 8:30 a.m.-12:30 p.m. -

Archaeology and Calgary Parks Territorial Acknowledgement Table of Contents Contributors Explore Archaeology

UNCOVERING HUMAN HISTORY: Archaeology and Calgary Parks Territorial acknowledgement Table of Contents Contributors Explore Archaeology ........................................................... 2 10 Glenmore Parks (North and South) .........................32 We would like to take this opportunity to Amanda Dow Cultural Timeline ..................................................................... 4 11 Griffith Woods ..................................................................34 acknowledge that Indigenous people were Anna Rebus Cultural Context – Archaeologically Speaking ............ 6 12 Haskayne Legacy Park ..................................................35 the first stewards of this landscape - using 13 Inglewood Bird Sanctuary ...........................................36 it for sustenance, shelter, medicine and Circle CRM Group Inc. Explore Calgary’s Parks....................................................... 8 14 Nose Hill Park ...................................................................38 ceremony. Calgary’s landscape falls within Bison Historical Services Calgary’s Parks and Waterways ......................................... 9 15 Paskapoo Slopes and the traditional territories of the people Calgary’s Waterways and Parks Pathways ...................10 Golder Associates Ltd. Valley Ridge Natural Area Parks ................................40 of Treaty 7. This includes: the Blackfoot Know History Waterways ............................................................................... 11 16 Pearce Estate Park ..........................................................42 -

The Official Hamptons Community Newsletter for Hamptons Covid-19 Updates, Please See Hamptonscalgary.Ca

JUNE 2020 DELIVERED MONTHLY TO 2,500 HOUSEHOLDS your HAMPTONS THE OFFICIAL HAMPTONS COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER FOR HAMPTONS COVID-19 UPDATES, PLEASE SEE HAMPTONSCALGARY.CA FOLLOW US ON TWITTER & FACEBOOK Certified Specialist in Adult & Children Orthodontics Dr. C. Todd Lee-Knight DMD. MSc, Cert Ortho 7 4 5 5 6 ~ Clear Aligners ~ Traditional Braces ~ Clear Braces ~ Surgical cases Call for a Complimentary Consultation! 3 9 2 Suite 246, 5149 Country Hills Blvd. N.W., Calgary AB T3A 5K8 W: orthogroup.ca ~ E: [email protected] ~ P: 403-208-8080 4 1 3 7 9 5 4 Long wedding veils have 7 4 8 5 2 been a trend for many years; how- ever, the length of these veils often 6 9 8 varies, and some are much longer than others. How long, do you ask? Well, the 8 5 Guinness World Record for the longest veil is 23,000 feet, which is more than 6 5 3 63 football fields in length. FIND SOLUTION ON PAGE 9 Cambridge Opening Manor June 2020 Introducing Cambridge Manor The Brenda Strafford Foundation’s newest seniors wellness community The Brenda Strafford Foundation was in University District, NW Calgary’s newest urban neighbourhood. proudly awarded ‘Accreditation with Cambridge Manor | University District Exemplary Status’ (Accreditation Canada) 403-536-8675 and ‘Innovator of the Year’ (Alberta [email protected] Continuing Care Association) in 2018. Visit us online at: cambridgemanor.ca | theBSF.ca NITANISAK DISTRICT Girl Guides during the Pandemic Although Girl Guides has been “paused” in terms of in- News from the person unit meetings since mid-March, there are still Friends of Nose Hill lots of activities going on. -

Calgary Parks & Pathway Bylaw Review

Calgary Parks & Pathway Bylaw Review Stakeholder Report Back: What we Heard May 4, 2018 Project overview A parks bylaw is a set of rules to regulate the actions and behaviours of park users. These rules are intended to protect park assets, promote safety and provide a safe and enjoyable experience for park users. The Parks and Pathway Bylaw was last reviewed in 2003. Since then the way we use parks has evolved. For example, in recent years goats have been introduced to our parks to help manage weeds, Segways have been seen on pathways and new technologies, such as drones, have become more commonplace. Engagement overview Engagement sought to understand what is important to you in terms of your park usage as part of this Bylaw review to better assess your usage and as a result, our next steps. Engagement is one area that will help us as we review the Parks and Pathway Bylaw. In addition to your input, we are looking into 3-1-1 calls, other reports and best practices from other cities. In alignment with City Council’s Engage Policy, all engagement efforts, including this project are defined as: Purposeful dialogue between The City and citizens and stakeholders to gather meaningful information to influence decision making. As a result, all engagement follows the following principles: Citizen-centric: focusing on hearing the needs and voices of both directly impacted and indirectly impacted citizens Accountable: upholding the commitments that The City makes to its citizens and stakeholders by demonstrating that the results and outcomes of the engagement processes are consistent with the approved plans for engagement Inclusive: making best efforts to reach, involve, and hear from those who are impacted directly or indirectly Committed: allocating sufficient time and resources for effective engagement of citizens and stakeholders Responsive: acknowledging citizen and stakeholder concerns Transparent: providing clear and complete information around decision processes, procedures and constraints. -

Green Notes 50Th Anniversary Newsletter Like a Beautiful Tree, CPAWS Southern Alberta Comes from Strong Roots and Has Grown Into a Magestic Forest

FALL/WINTER 2017/18 GREEN NOTES 50TH ANNIVERSARY NEWSLETTER Like a beautiful tree, CPAWS Southern Alberta comes from strong roots and has grown into a magestic forest. THIS EDITION OF GREEN NOTES CELEBRATES OUR 50 YEAR HISTORY. SOUTHERN ALBERTA CHAPTER 50TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Branching Out Local Work with a National Voice • 12 Welcome Messages A Time of Significant Change • 12 National President • 3 A Sense of Accomplishment and Urgency • 13 National Executive Director • 3 Education as a Conservation Strategy • 14 Southern Alberta Executive Director • 4 Volunteerism: The Lifeblood of CPAWS • 15 Our Roots Volunteer Profile: Gord James • 15 The Conservation Movement Awakens • 6 The Canopy and Beyond Canadian National Parks: Today and Tomorrow • 7 20 Years of Innovative Education • 16 Public Opposition and University Support • 8 Reflecting While Looking to the Future • 18 An Urban Conservation Legacy • 9 Alberta Needs CPAWS • 19 An Era of Protest • 9 CHAPTER TEAM CHAPTER BOARD OF DIRECTORS Anne-Marie Syslak, Executive Director Andre De Leebeeck, Secretary Katie Morrison, Conservation Director Jim Donohue, Treasurer, Vice Chair Jaclyn Angotti, Education Director Doug Firby Kirsten Olson, Office & Fund Program Administrator Ross Glenfield Ian Harker, Communications Coordinator Jeff Goldberg Alex Mowat, Hiking Guide Steve Hrudey Julie Walker, Hiking Guide Kathi Irvine Justin Howse, Hiking Guide Sara Jaremko Vanessa Bilan, Hiking Guide, Environmental Educator Peter Kloiber Lauren Bally, Hiking Guide Megan Leung Edita Sakarova, Bookkeeper Jon Mee Cinthia Nemoto CONTACT INFORMATION Phil Nykyforuk, Chair CPAWS Southern Alberta Chapter [email protected] EDITORIAL AND DESIGN www.cpaws-southernalberta.org Doug Firby Ian Harker, Communications Coordinator Green Notes Newsletter is published by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Southern Alberta Chapter (CPAWS Cover Photo: John E. -

The Scenic Geology of Calgary – a Walk at Nose Hill – Dale Leckie 1

The Scenic Geology of Calgary – A Walk at Nose Hill – Dale Leckie 1 The Scenic Geology of Calgary – A Walk at Nose Hill Nose Hill – so much geology to be seen Nose Hill Park is one of the best places to appreciate the geology of Calgary. The park overlooks the city and surrounding area, providing panoramic overviews in all directions. The Bow River valley is several kilometres wide and 200 metres deep, with a complicated geological history. The Rocky Mountains dominate the horizon to the west and the Plains stretch into the distance to the north, east and southeast. Directions Nose Hill Park and the associated hikes are best accessed from two locations. For the best overviews of the Bow River valley, the Rocky Mountains to the west, and to picture the glaciations and Glacial Lake Calgary, park at Edgemont Boulevard parking lot at the intersection of Shaganappi Trail and Edgemont Boulevard. A second location for an overview and to access the glacial erratic, park at the 64th Avenue parking lot, at the intersection of 14 Street NW and 64 Avenue. Use the figure below as a reference to the Scenic Geology of Calgary, as viewed from Nose Hill. The Scenic Geology of Calgary – A Walk at Nose Hill – Dale Leckie 2 • Meandering river sands and floodplain mudstones of the Paleocene Porcupine Hills Formation extend down about 600 metres below the city. These ancient rivers flowed into Alberta during the last mountain-building phase of the Rocky Mountains 62.5 to 58.5 million years ago. Sediment originated from the ancestral Rocky Mountains at the time. -

The Go D in Them There Hills

~-----..- --. • l No;35 • Winter 2000 L-__~~_~ _____ ,-~~~~~~~~~TheNewsletter~ of the Alberta Native P1antCouncii In this issue... Alberta's Natural Landscapes-backyardto pipeline AGM 2000 ............................. 1 The 13th ANPC Annual General Meeting and Workshop, April 29-30, Calgary Zoo Botany AB ............................. 1 President's message ......... 2 Ruth Johnson Call for Nominations ......... 2 .' Little Mountain ................... 3 Be sure to attend this year's ANPC workshop for sa le, guided tours of the naturalised areas at Good, Bad & Ugly ............... 4 Recreating Alberta ~' Natural Landswpes the<zoo and lots of opportunity to share Ideas Counting Crocuses ............ 6 Backyard 10 Pipeline, April 29 and 30 at the and learn from other workshop participants. Rare plant communities .. 8 Calga ry Zoo. The ANPC is working in con Saturday evening's banquet is not to be Book reviews ....................... 11 junction with the Calgary Zoo to plan this missed-cline amidst the vegetation of the News and notes .................. 15 exciting and inspiring workshop. You can Botani cal Conserva tory and listen to the Zoo's expect informative topics, interesting people, renowned Brian Keating spin his tales of the good food---:-all in a 'plantful' setting. Who 'Alpine High Life ' . Sunday will provide work could ask for more? shop participants the opportunity to stretch Saturday sessions will cover examples of their legs and do some hands-on naturalisation naturalisation projects (urban settings, foothills work o n our field trip. and prairie areas, mountain parks ,md home The Calgary Zoo is generously assis ting projects), a variety of industrial natu ralisati o n ANPC with adve rtising and promotion so it is and res torati on proJ ec ts, creating backyard expected that this workshop will be well habitat. -

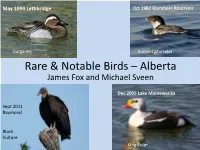

Alberta James Fox and Michael Sveen

May 1990 Lethbridge Oct 1982 Glenmore Reservoir Garganey Ancient Murrelet Rare & Notable Birds – Alberta James Fox and Michael Sveen Dec 2005 Lake Minnewanka Sept 2011 Raymond Black Vulture King Eider North American Birds Who? What? Where? When? Why? How? North American Birds is a journal published by the American Bird Association. North American Birds • ‘journal of record’ for birders • mission is to provide a complete overview of the changing panorama of North America’s birdlife including: – outstanding records – range extensions and contractions – population dynamics – change in migration patterns – change in seasonal occurrence. Winter (December to February) Spring (March to May) Four issues per year: Summer (June to July) Fall (August to November) In each issue you will find • thirty-four (34) regional reports organized taxonomically and produced by some of North America’s top birders • A comprehensive summary of an entire season including: – If migration was early or late – Nesting season success by species – Which irruptive species invaded and where – Species range expansion or contraction – Species in decline – Where rare birds were found – Information for planning your next birding trip Alberta Record Compilers • Compilers – James Fox – Michael Sveen – Milton Spitzer – Yousif Attia • Advisors – Dr. Jocelyn Hudon – Michael Harrison Alberta is part of the PRAIRIE PROVINCES REGION with Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Compiling Records • A team of birders, ornithologists and biologists work together to collect and compile rare and notable bird records from all over Alberta. An Alberta report is written using these records. • The PRAIRIE PROVINCE REGIONAL editors use the provincial reports to write a region wide report that is published in the North American Birds Journal. -

Calgary District Lacrosse Boundary Map

Calgary District Lacrosse Boundary Map 03W AXEMEN Communities: Acadia, Auburn Bay, Bonavista Downs, Chaparral, Copperfield, Cranston, Deer Ridge, Rockyview Deer Run, Diamond Cove, Douglas Dale/Glen, Fairview, Lake Bonavista, Legacy, Mahogany, Maple 02L Ridge, McKenzie Lake, McKenzie Towne, Midnapore, New Brighton, Parkland, Queensland, Riverbend, Seton, Sundance, Walden, Willow Park South: Township Road 222/210 Avenue East: Range Road 282/Range Road 281 02K McDonald Lake LIVINGSTON 144 AV NW S North: 450th Ave Y HIGH RIVER M O p West: No defined Boundary N CARR IN GTON S 03H V 03D A South/East: need to contact SALA L L 03I E Y SAGE HILL DR NW STONEY R SAGE D 4 02B N HILL W 02C NOLAN S A HILL R ROCKY RIDGE RD NW C E E N T ST HILLS BV R EVANSTON E V N R W W Communities: Arbour Lake, Banff Trail, Bowness, Brentwood, Cambrian Heights, Capital Hill, A N HORNETS H T REDSTONE S Charleswood, Citadel, Collingwood, Crestmont, Dalhousie, Edgemont, Evanston, 7 3 02A Greenwood/GreenBriar, Hamptons, Hawkwood, Hidden Valley, Highwood, Hillhurst, Hounsfield NW BV NW EVANSPARK 85 ST NW 85 AV SYMONS VALLEY PY NW 128 Heights/ Briar Hill, Kincora, MacEwan Glen, Montgomery, Mount Pleasant, Nolan Hill, North Haven, COVENTRY Nose Hill Park, Parkdale, Point McKay, Queens Park Village, Ranchlands, RockyRidge, Rosedale, N PA AT NE ST 15 ELL HILLS STONEY BV NE 128 AV NE BV A NW Rosemont, Royal Oak, Royal Vista, Sage Hill, Sandstone Valley, Scenic Acres, Sherwood, Silver STONEGATE E Hornets N LANDING R T Springs, St Andrews Heights, Sunnyside, Tuscany, University